Term symbol

In quantum mechanics, the Russell-Saunders [1] term symbol is an abbreviated description of the angular momentum quantum numbers in a multi-electron atom. Each energy level of a given electron configuration is described by its own term symbol, assuming LS coupling. The ground state term symbol is predicted by Hund's rules. Tables of atomic energy levels identified by their term symbols have been compiled by NIST.[2]

Symbol

The term symbol has the form

- 2S+1LJ

where

- S is the total spin quantum number. 2S + 1 is the spin multiplicity: the maximum number of different possible states of J for a given (L, S) combination.

- J is the total angular momentum quantum number.

- L is the total orbital quantum number in spectroscopic notation. The first 17 symbols of L are:

| L = | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ... |

| S | P | D | F | G | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | Q | R | T | U | V | (continued alphabetically)[note 1] |

The nomenclature (S, P, D, F) is derived from the characteristics of the spectroscopic lines corresponding to (s, p, d, f) orbitals: sharp, principal, diffuse, and fundamental; the rest being named in alphabetical order. When used to describe electron states in an atom, the term symbol usually follows the electron configuration. For example, one low-lying energy level of the carbon atom state is written as 1s22s22p2 3P2. The superscript 3 indicates that the spin state is a triplet, and therefore S = 1 (2S + 1 = 3), the P is spectroscopic notation for L = 1, and the subscript 2 is the value of J. Using the same notation, the ground state of carbon is 1s22s22p2 3P0.[2]

Others

The term symbol is also used to describe compound systems such as mesons or atomic nuclei, or even molecules (see molecular term symbol). In that last case, Greek letters are used to designate the (molecular) orbital angular momenta.

For a given electron configuration

- The combination of an S value and an L value is called a term, and has a statistical weight (i.e., number of possible microstates) of (2S+1)(2L+1);

- A combination of S, L and J is called a level. A given level has a statistical weight of (2J+1), which is the number of possible microstates associated with this level in the corresponding term;

- A combination of L, S, J and MJ determines a single state.

As an example, for S = 1, L = 2, there are (2×1+1)(2×2+1) = 15 different microstates corresponding to the 3D term, of which (2×3+1) = 7 belong to the 3D3 (J = 3) level. The sum of (2J+1) for all levels in the same term equals (2S+1)(2L+1). In this case, J can be 1, 2, or 3, so 3 + 5 + 7 = 15.

Term symbol parity

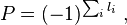

The parity of a term symbol is calculated as

where li is the orbital quantum number for each electron. In fact, only electrons in odd orbitals contribute to the total parity: an odd number of electrons in odd orbitals (those with an odd l such as in p, f,...) will make an odd term symbol, while an even number of electrons in odd orbitals will make an even term symbol, irrespective of the number of electrons in even orbitals.

When it is odd, the parity of the term symbol is indicated by a superscript letter "o", otherwise it is omitted:

- 2Po

½ has odd parity, but 3P0 has even parity.

Alternatively, parity may be indicated with a subscript letter "g" or "u", standing for gerade (German for "even") or ungerade ("odd"):

- 2P½,u for odd parity, and 3P0,g for even.

Ground state term symbol

It is relatively easy to calculate the term symbol for the ground state of an atom using Hund's rules. It corresponds with a state with maximal S and L.

- Start with the most stable electron configuration. Full shells and subshells do not contribute to the overall angular momentum, so they are discarded.

- If all shells and subshells are full then the term symbol is 1S0.

- Distribute the electrons in the available orbitals, following the Pauli exclusion principle. First, fill the orbitals with highest ml value with one electron each, and assign a maximal ms to them (i.e. +½). Once all orbitals in a subshell have one electron, add a second one (following the same order), assigning ms = −½ to them.

- The overall S is calculated by adding the ms values for each electron. That is the same as multiplying ½ times the number of unpaired electrons. The overall L is calculated by adding the ml values for each electron (so if there are two electrons in the same orbital, add twice that orbital's ml).

- Calculate J as

- if less than half of the subshell is occupied, take the minimum value J = |L - S|;

- if more than half-filled, take the maximum value J = L + S;

- if the subshell is half-filled, then L will be 0, so J = S.

As an example, in the case of fluorine, the electronic configuration is 1s22s22p5.

1. Discard the full subshells and keep the 2p5 part. So there are five electrons to place in subshell p (l = 1).

2. There are three orbitals (ml = 1, 0, −1) that can hold up to 2(2l + 1) = 6 electrons. The first three electrons can take ms = ½ (↑) but the Pauli exclusion principle forces the next two to have ms = −½ (↓) because they go to already occupied orbitals.

| ml | |||

| +1 | 0 | −1 | |

| ms: | ↑↓ | ↑↓ | ↑ |

3. S = ½ + ½ + ½ − ½ − ½ = ½; and L = 1 + 0 − 1 + 1 + 0 = 1, which is "P" in spectroscopic notation.

4. As fluorine 2p subshell is more than half filled, J = L + S = 3⁄2. Its ground state term symbol is then 2S+1LJ = 2P3⁄2.

Term symbols for an electron configuration

To calculate all possible term symbols for a given electron configuration the process is a bit longer.

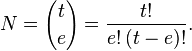

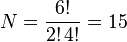

- First, calculate the total number of possible microstates N for a given electron configuration. As before, we discard the filled (sub)shells, and keep only the partially filled ones. For a given orbital quantum number l, t is the maximum allowed number of electrons, t = 2(2l+1). If there are e electrons in a given subshell, the number of possible microstates is

- As an example, lets take the carbon electron structure: 1s22s22p2. After removing full subshells, there are 2 electrons in a p-level (l = 1), so we have

- different microstates.

- Second, draw all possible microstates. Calculate ML and MS for each microstate, with

where mi is either ml or ms for the i-th electron, and M represents the resulting ML or MS respectively:

where mi is either ml or ms for the i-th electron, and M represents the resulting ML or MS respectively:

ml +1 0 −1 ML MS all up ↑ ↑ 1 1 ↑ ↑ 0 1 ↑ ↑ −1 1 all down ↓ ↓ 1 −1 ↓ ↓ 0 −1 ↓ ↓ −1 −1 one up one down

↑↓ 2 0 ↑ ↓ 1 0 ↑ ↓ 0 0 ↓ ↑ 1 0 ↑↓ 0 0 ↑ ↓ −1 0 ↓ ↑ 0 0 ↓ ↑ −1 0 ↑↓ −2 0

- Third, count the number of microstates for each ML—MS possible combination

MS +1 0 −1 ML +2 1 +1 1 2 1 0 1 3 1 −1 1 2 1 −2 1

- Fourth, extract smaller tables representing each possible term. Each table will have the size (2L+1) by (2S+1), and will contain only "1"s as entries. The first table extracted corresponds to ML ranging from −2 to +2 (so L = 2), with a single value for MS (implying S = 0). This corresponds to a 1D term. The remaining table is 3×3. Then we extract a second table, removing the entries for ML and MS both ranging from −1 to +1 (and so S = L = 1, a 3P term). The remaining table is a 1×1 table, with L = S = 0, i.e., a 1S term.

S=0, L=2, J=2

1D2

Ms 0 Ml +2 1 +1 1 0 1 −1 1 −2 1 S=1, L=1, J=2,1,0

3P2, 3P1, 3P0

Ms +1 0 −1 Ml +1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 −1 1 1 1 S=0, L=0, J=0

1S0

Ms 0 Ml 0 1

- Fifth, applying Hund's rules, deduce which is the ground state (or the lowest state for the configuration of interest.) Hund's rules should not be used to predict the order of states other than the lowest for a given configuration. (See examples at Hund's rules#Excited states.)

- If only two equivalent electrons are involved, there is an "Even Rule" which states

- For two equivalent electrons the only states that are allowed are those for which the sum (L + S) is even.

Case of three equivalent electrons

- For three equivalent electrons (with the same orbital quantum number l), there is also a general formula (denoted by X(L,S,l) below) to count the number of any allowed terms with total orbital quantum number "L" and total total spin quantum number "S".

where the floor function  denotes the greatest integer not exceeding x.

denotes the greatest integer not exceeding x.

The detailed proof could be found in Renjun Xu's original paper.[3]

- For a general electronic configuration of lk, namely k equivalent electrons occupying one subshell, the general treatment and computer code could also be found in this paper.[3]

Alternative method using group theory

For configurations with at most two electrons (or holes) per subshell, an alternative and much quicker method of arriving at the same result can be obtained from group theory. The configuration 2p2 has the symmetry of the following direct product in the full rotation group:

- Γ(1) × Γ(1) = Γ(0) + [Γ(1)] + Γ(2),

which, using the familiar labels Γ(0) = S, Γ(1) = P and Γ(2) = D, can be written as

- P × P = S + [P] + D.

The square brackets enclose the anti-symmetric square. Hence the 2p2 configuration has components with the following symmetries:

- S + D (from the symmetric square and hence having symmetric spatial wavefunctions);

- P (from the anti-symmetric square and hence having an anti-symmetric spatial wavefunction).

The Pauli principle and the requirement for electrons to be described by anti-symmetric wavefunctions imply that only the following combinations of spatial and spin symmetry are allowed:

- 1S + 1D (spatially symmetric, spin anti-symmetric)

- 3P (spatially anti-symmetric, spin symmetric).

Then one can move to step five in the procedure above, applying Hund's rules.

The group theory method can be carried out for other such configurations, like 3d2, using the general formula

- Γ(j) × Γ(j) = Γ(2j) + Γ(2j-2) + ... + Γ(0) + [Γ(2j-1) + ... + Γ(1)].

The symmetric square will give rise to singlets (such as 1S, 1D, & 1G), while the anti-symmetric square gives rise to triplets (such as 3P & 3F).

More generally, one can use

- Γ(j) × Γ(k) = Γ(j+k) + Γ(j+k-1) + ... + Γ(|j-k|)

where, since the product is not a square, it is not split into symmetric and anti-symmetric parts. Where two electrons come from inequivalent orbitals, both a singlet and a triplet are allowed in each case. [4]

Notes

- ↑ There is no official convention for naming angular momentum values greater than 20 (symbol Z). Many authors begin using Greek letters at this point (

...). The occasions for which such notation is necessary are few and far between, however.

...). The occasions for which such notation is necessary are few and far between, however.

References

- ↑ RS, Russell, H. N.; Saunders, F. A. (1925). "New Regularities in the Spectra of the Alkaline Earths". Astrophysical Journal 61: 38. Bibcode:1925ApJ....61...38R. doi:10.1086/142872.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 NIST Atomic Spectrum Database To read the carbon atom levels, type "C I" in the Spectrum box and click on Retrieve data. In this database, neutral atoms are identified as I, singly ionized atoms as II, etc.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Xu, Renjun; Z. Dai (2006). "Alternative mathematical technique to determine LS spectral terms". Journal of Physics B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 39: 3221–3239. arXiv:physics/0510267. Bibcode:2006JPhB...39.3221X. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/39/16/007.

- ↑ McDaniel, Darl H. (1977). "Spin factoring as an aid in the determination of spectroscopic terms". Journal of Chemical Education 54 (3): 147. Bibcode:1977JChEd..54..147M. doi:10.1021/ed054p147.

See also

- Angular quantum numbers

- Angular momentum coupling

- Molecular term symbol