Temple of Aphaea

| Temple of Aphaia Ναός Αφαίας (Greek) | |

|---|---|

Temple of Aphaia from the southeast. | |

| |

| Location | Agia Marina, Attica, Greece |

| Region | Saronic Gulf |

| Coordinates | 37°45′15″N 23°32′00″E / 37.75417°N 23.53333°ECoordinates: 37°45′15″N 23°32′00″E / 37.75417°N 23.53333°E |

| Type | Ancient Greek temple |

| Length | 80 m (260 ft) |

| Width | 80 m (260 ft) |

| Area | 640 m2 (6,900 sq ft) |

| History | |

| Founded | Circa 500 BC |

| Periods | Archaic Greek to Hellenistic |

| Satellite of | Aegina, then Athens |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Erect with collapsed roof |

| Ownership | Public |

| Management | 26th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism |

The Temple of Aphaia (Greek: Ναός Αφαίας) or Afea[1] is located within a sanctuary complex dedicated to the goddess Aphaia on the Greek island of Aigina, which lies in the Saronic Gulf. It stands on a c. 160 m peak on the eastern side of the island approximately 13 km east by road from the main port.[2]

Aphaia (Greek Ἀφαία) was a Greek goddess who was worshipped exclusively at this sanctuary. The extant temple of c. 500 BC was built over the remains of an earlier temple of c. 570 BC, which was destroyed by fire c. 510 BC. The elements of this destroyed temple were buried in the infill for the larger, flat terrace of the later temple, and are thus well preserved. Abundant traces of paint remain on many of these buried fragments. There may have been another temple in the 7th century BC, also located on the same site, but it is thought to have been much smaller and simpler in terms of both plan and execution. Significant quantities of Late Bronze Age figurines have been discovered at the site, including proportionally large numbers of female figurines (kourotrophoi), indicating – perhaps – that cult activity at the site was continuous from the 14th century BC, suggesting a Minoan connection for the cult.[3] The last temple is of an unusual plan and is also significant for its pedimental sculptures, which are thought to illustrate the change from Archaic to Early Classical technique. These sculptures are on display in the Glyptothek of Munich, with a number of fragments located in the museums at Aigina and on the site itself.[4]

Exploration and archaeology

The periegetic writer Pausanias briefly mentions the site in his writings of the 2nd century AD, but does not describe the sanctuary in detail as he does for many others.[5] The temple was made known in Western Europe by the publication of the Antiquities of Ionia (London, 1797). In 1811, the young English architect Charles Robert Cockerell, finishing his education on his academic Grand Tour, and Baron Otto Magnus von Stackelberg removed the fallen fragmentary pediment sculptures. On the recommendation of Baron Carl Haller von Hallerstein, who was also an architect and, moreover, a protégé of the art patron Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria, the marbles were shipped abroad and sold the following year to the Crown Prince, soon to be King Ludwig I of Bavaria. Minor excavations of the east peribolos wall were carried out in 1894 during reconstruction of the last temple.

Systematic excavations at the site were carried out in the 20th century by the German School in Athens, at first under the direction of Adolf Furtwängler. The area of the sanctuary was defined and studied during these excavations. The area under the last temple could not be excavated, however, because that would have harmed the temple. In addition, significant remains from the Bronze Age were detected in pockets in the rocky surface of the hill. From 1966 to 1979, an extensive second German excavation under Dieter Ohly was performed, leading to the discovery in 1969 of substantial remains of the older Archaic temple in the fill of the later terrace walls. Ernst-Ludwig Schwandner and Martha Ohly were also associated with this dig, which continued after the death of Dieter Ohly until 1988. Sufficient remains were recovered to allow a complete architectural reconstruction of the structure to be extrapolated; the remains of the entablature and pediment of one end of the older temple have been reconstructed in the on-site museum.

Phases of the sanctuary

|

|

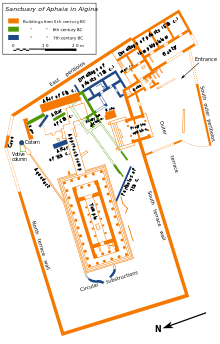

The sanctuary of Aphaia was located on the top of a hill c. 160 m in elevation at the northeast point of the island. The last form of the sanctuary covered an area of c. 80 by 80 m; earlier phases were less extensive and less well defined.

Bronze Age phase

In its earliest phase of use during the Bronze Age, the eastern area of the hilltop was an unwalled, open-air sanctuary to a female fertility and agricultural deity.[3] Bronze Age figurines outnumber remains of pottery. Open vessel forms are also at an unusually high proportion versus closed vessels. There are no known settlements or burials in the vicinity, arguing against the remains being due to either usage. Large numbers of small pottery chariots and thrones and miniature vessels have been found. Although there are scattered remains dating to the Early Bronze Age such as two seal stones, remains in significant quantities begin to be deposited in the Middle Bronze Age, and the sanctuary has its peak use in the LHIIIa2 through LHIIIb periods. It is less easy to trace the cult through the Sub-Mycenean period and into the Geometric where cult activity is once more reasonably certain.

Late Geometric phase

Furtwängler proposes three phases of building at the sanctuary, with the earliest of these demonstrated by an altar at the eastern end dating to c. 700 BC. Also securely known are a cistern at the northeast extremity and a structure identified as a treasury east of the propylon (entrance) of the sanctuary. The temple corresponding to these structures is proposed to be under the later temples and thus not able to be excavated. Furtwängler suggests that this temple is the oikos (house) referenced in a mid-7th-century BC inscription from the site as having been built by a priest for Aphaia; he hypothesizes that this house of the goddess (temple) was built of stone socles topped with mud brick upper walls and wooden entablature.[7] The top of the hill was slightly modified to make it more level by wedging stones into the crevices of the rock.

Archaic phase (Aphaia Temple I)

Ohly detected a (stone socle and mudbrick upper level) peribolos wall enclosing an area of c. 40 by 45 m dating to this phase. This peribolos was not aligned to the axis of the temple. A raised and paved platform was built to connect the temple to the altar. There was a propylon (formal entrance gate) with a wooden superstructure in the southeast side of the peribolos. A 14 m tall column topped by a sphinx was at the northeast side of the sanctuary. The full study and reconstruction of the temple was done by Schwandner, who dates it to before 570 BC. In his reconstruction, the temple is prostyle-tetrastyle in plan, and has a pronaos and – significantly – an adyton at the back of the cella. As is the case at the temples of Artemis at Brauron and Aulis (among others), many temples of Artemis have such back rooms, which may indicate a similarity of cult practice.[8] The cella of the temple of Aphaia had the unusual feature of having two rows of two columns supporting another level of columns that reached the roof. The architrave of this temple was constructed in two courses, giving it a height of 1.19 m versus the frieze height of 0.815 m; this proportion is unusual among temples of the region, but is known from temples in Sicily. A triglyph and metope frieze is also placed along the inside of the pronaos.[9] These metopes were apparently undecorated with sculpture, and there is no evidence of pedimental sculptural groups. This temple and much of the sanctuary was destroyed by fire around 510 BC.

Late Archaic Phase (Aphaia Temple II)

Construction of a new temple commenced soon after the destruction of the older temple. The remains of the destroyed temple were removed from the site of the new temple and used to fill a c. 40 by 80 m terrace within the overall sanctuary of c. 80 by 80 m. This new temple terrace was aligned on north, west, and south with the plan of the new temple. The temple was a hexastyle peripteral Doric order structure on a 6 by 12 column plan resting on a 15.5 by 30.5 m platform; it had a distyle in antis cella with an opisthodomos and a pronaos.[10] All but three of the outer columns were monolithic. There was a small, off-axis doorway between the cella and the opisthodomos. In similar design but more monumental execution than the earlier temple, the cella of the new temple had two rows of five columns, supporting another level of columns that reached to roof. The corners of the roof were decorated with sphinx acroteria, and the central, vegetal acroterion of each side had a pair of kore statues standing one on either side, an unusual feature. The antefixes were of marble, as were the roof tiles.

Dates ranging from 510 to 470 BC have been proposed for this temple. Bankel, who published the complete study of the remains, compares the design features of the structure with three structures that were near contemporaries:

- The Athenian Treasury at Delphi

- The Doric Temple in the Marmaria area of Delphi

- The temple of Artemis at Delion on Paros

Bankel says the temple of Aphaia is more developed than the earlier phase of this structure, giving it a date of around 500 BC. The metopes of this temple, which were not found, were slotted into the triglyph blocks and attached to backer blocks with swallowtail clamps. If they were wooden, their lack of preservation is to be expected. If they were stone, then they may have been removed for the ancient antiquities market while the structure was still standing.[11] The altar was redone for this phase as well.

Pedimental sculptures

The marbles from the Late Archaic temple of Aphaia, comprising the sculptural groups of the east and west pediments of the temple, are on display in the Glyptothek of Munich, where they were restored by the Danish neoclassic sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen. These works exerted a formative influence on the local character of Neoclassicism in Munich, as exhibited in the architecture of Leo von Klenze. Each pediment centered on the figure of Athena, with groups of combatants, fallen warriors, and arms filling the decreasing angles of the pediments. The theme shared by the pediments was the greatness of Aigina as shown by the exploits of its local heroes in the two Trojan wars, one lead by Heracles against Laomedon and a second lead by Agamemnon against Priam. According to the standard myths, Zeus raped the nymph Aigina, who bore the first king of the island, Aiakos. This king had the sons Telamon (father of the Homeric hero Ajax) and Peleus (father of the Homeric hero Achilles). The sculptures preserve extensive traces of a complex paint scheme, and are crucial for the study of painting on ancient sculpture. The marbles are finished even on the back surfaces of the figures, despite the fact that these faced the pediment and were thus not visible.

Ohly had contended that there were four total pedimental groups (two complete sets of pediments for the east and west sides of the temple); Bankel uses the architectural remains of the temple to argue that there were only three pedimental groups; later in his life, Ohly came to believe that there were only two, which was shown persuasively by Eschbach.[12] There were shallow cuttings and many dowels used to secure the plinths of the sculptures of the west pediment (the back of the temple). The east pediment used deep cuttings and fewer dowels to secure the plinths of the statues. There were also a number of geison blocks that had shallow cuttings and many dowels like the west pediment, but that did not fit there. Bankel argues that sculptures were set on both the east and the west pediments with these shallow cuttings, but that the sculptures of the east pediment were removed (along with the geison blocks cut to receive them) and replaced with a different sculptural group. This replacement appears to have been carried out before the raking geisa were installed on the east pediment, since the corner geisa were not cut down to join to the raking geisa: i.e. the 1st phase of the east pediment was replaced with the 2nd phase before that end of the temple was completed. As the eastern facade of the temple (the front) was the most important visually, it is not surprising that the builders would choose to focus additional efforts on it.

Eastern pediment

The first Trojan war, not the one described by Homer but the war of Heracles against the king of Troy Laomedon is the theme, with Telamon figuring prominently as he fights alongside Heracles against king Laomedon. This pediment is thought to be later than the west pediment and to show a number of features appropriate to the Classical period: the statues show a dynamic posture especially in the case of Athena, chiastic composition, and intricate filling of the space using the legs of fallen combatants to fill the difficult decreasing angles of the pediment. Part of the eastern pediment was destroyed during the Persian Wars, possibly by a thunderbolt. The statues that survived were set up in the sanctuary enclosure, and those that were destroyed, were buried according to the ancient custom. The old composition was replaced by a new one with a scene of a battle, again with Athena at the center.[13]

Western pediment

The second Trojan war – the one described by Homer – is the theme, with Ajax (son of Telamon) figuring prominently. The style of these sculptures is that of the Archaic period. The composition deals with the decreasing angles of the pediment by filling the space using a shield and a helmet.

See also

- Greek architecture

- Greek temple

- List of Greco-Roman roofs

References

- ↑ The name Afea appears on all the local signs, Afea being the name of a Cretan woman of unsurpassed beauty. After escaping an unwelcome marriage on Crete, she was rescued by a fisherman from Aegina. In payment for this he also proposed an unwelcome marriage. So Afea headed out of Aghia Marina towards the mountain top where she vanished at the current site of the temple, where it is said that the fisherman established a shrine believing Afea to have been taken by the gods.

- ↑ The main port and the main city are named Aigina, after the island. The Temple of Aphaia is 9.6 km east of this city. The sanctuary is also 29.5 km southwest of the Acropolis of Athens, which is visible across the gulf on a clear day.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Pilafidis-Williams argues that the character and relative proportions of the finds leads to the conclusion that the deity worshiped was a female fertility/agricultural goddess.

- ↑ The important Bronze Age archaeological site of Kolona is northwest of Aigina (the main city) along the coast, and a museum is located at this site. The museum at Aigina was the first institution of its kind in Greece, but most of the collection (other than a collection of bas relief panels from Delos) was transferred to Athens in 1834 (EB), where it can be seen in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. The museum on the site contains a restoration of the Early Archaic temple entablature and pediment, as well as copies of elements of the pedimental sculpture of the Late Archaic temple set into restored sections of the pediment.

- ↑ Description of Greece 2.30.3

On Aigina as one goes toward the mountain of Pan-Greek Zeus, the sanctuary of Aphaia comes up, for whom Pindar composed an ode at the behest of the Aeginetans. The Cretans say (the myths about her are native to Crete) that Euboulos was the son of Karmanor, who purified Apollo of the killing of the Python, and they say that Britomaris was the daughter of Zeus and Karme (the daughter of this Euboulos). She enjoyed races and hunts and was particularly dear to Artemis. While fleeing from Minos, who lusted after her, she cast herself into nets cast for a catch of fish. Artemis made her a goddess, and not only the Cretans but also the Aeginetans reverence her. The Aeginetans say that Britomaris showed herself to them on their island. Her epithet among the Aeginetans is Aphaia, and it is Diktynna on Crete.

- ↑ "East and West Pediments, Temple of Aphaia, Aegina". smARThistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ↑ Ohly disputes that there is sufficient evidence for this oikos structure.

- ↑ Hollinshead disputes that there is sufficient evidence for the presence of an adyton in this temple, and she questions whether similarity of form among temples of Artemis must indicate similarity of cult practice. This feature was not retained in the late Archaic temple, so its centrality to the cult practice is open to question.

- ↑ Schwandner wants this placement to refute the idea that triglyphs are meant to represent the ends of wooden beams.

- ↑ The use of the 6 by 12 plan of the Late Archaic period soon gave way to the Classical period preference for the proportions of the 6 by 13 plan and similar.

- ↑ Bankel notes that c. 80% of the triglyph blocks were damaged in a manner consistent with intentional breakage to remove the metopes.

- ↑ N. Eschbach, Die archaische Form in nacharchaischer Zeit: Untersuchungen zu Phänomenen der archaistischen Plastik des 5. und 4. Jhs. v. Chr.” Unpublished Habilitationschrift, University of Giessen.

- ↑ Leaflet "The Sanctuary of Aphaia on Aegina", Greek Ministry of Culture, Archaeological Receipts Fund, Athens 1998.

Sources

- Bankel, Hansgeorg. 1993. Der spätarchaische Tempel der Aphaia auf Aegina. Denkmäler antiker Architektur 19. Berlin; New York: W. de Gruyter.

- Cartledge, Paul, Ed., The Cambridge Illustrated History of Ancient Greece, Cambridge University Press:2002, p. 273.

- Cook, R. M. 1974. The Dating of the Aegina Pediments. Journal of Hellenic Studies, 94 pp. 171.

- Diebold, William J. 1995. The Politics of Derestoration: The Aegina Pediments and the German Confrontation with the Past. Art Journal, 54, no2 pp. 60–66.

- Furtwängler, Adolf, Ernst R. Fiechter and Hermann Thiersch. 1906. Aegina, das Heiligthum der Aphaia. München: Verlag der K. B. Akademie der wissenschaften in Kommission des G. Franz’schen Verlags (J. Roth).

- Furtwängler, Adolf. 1906. Die Aegineten der Glyptothek König Ludwigs I, nach den Resultaten der neuen Bayerischen Ausgrabung. München: Glyptothek: in Kommission bei A. Buchholz.

- Glancey, Jonathan, Architecture, Doring Kindersley, Ltd.:2006, p. 96.

- Invernizzi, Antonio. 1965. I frontoni del Tempio di Aphaia ad Egina. Torino: Giappichelli.

- Ohly, Dieter. 1977. Tempel und Heiligtum der Aphaia auf Ägina. München: Beck.

- Pilafidis-Williams, Korinna. 1987. The Sanctuary of Aphaia on Aigina in the Bronze Age. Munich: Hirmer Verlag.

- Schildt, Arthur. Die Giebelgruppen von Aegina. Leipzig : [H. Meyer], 1895.

- Schwandner, Ernst-Ludwig. 1985. Der ältere Porostempel der Aphaia auf Aegina. Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

- Webster, T. B. L. 1931. The Temple of Aphaia at Aegina. Journal of Hellenic Studies, 51, no2 pp. 179–183.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Temple of Aphaia. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Aegina. |

- Official website

- Pedimental Sculpture

- Temple of Aphaia Photographs

- (Hellenic Ministry of Culture) Archaeological site of Aphaia on Aigina

- German Wikipedia page for Dieter Ohly

- Ferdinand Pajor, "Cockerell and the 'Grand Tour'"

- Perseus website: "Aegina, Temple of Aphaia" Extensive photo repertory

- Adolf Furtwängler on the temple's polychromy, 1906

- The Museum of the Goddess Athena