Tautology (logic)

In logic, a tautology (from the Greek word ταυτολογία) is a formula which is true in every possible interpretation. Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein first applied the term to redundancies of propositional logic in 1921; (it had been used earlier to refer to rhetorical tautologies, and continues to be used in that alternate sense).

A formula is satisfiable if it is true under at least one interpretation, and thus a tautology is a formula whose negation is unsatisfiable. Unsatisfiable statements, both through negation and affirmation, are known formally as contradictions. A formula that is neither a tautology nor a contradiction is said to be logically contingent. Such a formula can be made either true or false based on the values assigned to its propositional variables. The double turnstile notation  is used to indicate that S is a tautology. Tautology is sometimes symbolized by "Vpq", and contradiction by "Opq". The tee symbol

is used to indicate that S is a tautology. Tautology is sometimes symbolized by "Vpq", and contradiction by "Opq". The tee symbol  is sometimes used to denote an arbitrary tautology, with the dual symbol

is sometimes used to denote an arbitrary tautology, with the dual symbol  (falsum) representing an arbitrary contradiction.

(falsum) representing an arbitrary contradiction.

Tautologies are a key concept in propositional logic, where a tautology is defined as a propositional formula that is true under any possible Boolean valuation of its propositional variables. A key property of tautologies in propositional logic is that an effective method exists for testing whether a given formula is always satisfied (or, equivalently, whether its negation is unsatisfiable).

The definition of tautology can be extended to sentences in predicate logic, which may contain quantifiers, unlike sentences of propositional logic. In propositional logic, there is no distinction between a tautology and a logically valid formula. In the context of predicate logic, many authors define a tautology to be a sentence that can be obtained by taking a tautology of propositional logic and uniformly replacing each propositional variable by a first-order formula (one formula per propositional variable). The set of such formulas is a proper subset of the set of logically valid sentences of predicate logic (which are the sentences that are true in every model).

History

The word tautology was used by the ancient Greeks to describe a statement that was true merely by virtue of saying the same thing twice, a pejorative meaning that is still used for rhetorical tautologies. Between 1800 and 1940, the word gained new meaning in logic, and is currently used in mathematical logic to denote a certain type of propositional formula, without the pejorative connotations it originally possessed.

In 1800, Immanuel Kant wrote in his book Logic:

- "The identity of concepts in analytical judgments can be either explicit (explicita) or non-explicit (implicita). In the former case analytic propositions are tautological."

Here analytic proposition refers to an analytic truth, a statement in natural language that is true solely because of the terms involved.

In 1884, Gottlob Frege proposed in his Grundlagen that a truth is analytic exactly if it can be derived using logic. But he maintained a distinction between analytic truths (those true based only on the meanings of their terms) and tautologies (statements devoid of content).

In 1921, in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Ludwig Wittgenstein proposed that statements that can be deduced by logical deduction are tautological (empty of meaning) as well as being analytic truths. Henri Poincaré had made similar remarks in Science and Hypothesis in 1905. Although Bertrand Russell at first argued against these remarks by Wittgenstein and Poincaré, claiming that mathematical truths were not only non-tautologous but were synthetic, he later spoke in favor of them in 1918:

- "Everything that is a proposition of logic has got to be in some sense or the other like a tautology. It has got to be something that has some peculiar quality, which I do not know how to define, that belongs to logical propositions but not to others."

Here logical proposition refers to a proposition that is provable using the laws of logic.

During the 1930s, the formalization of the semantics of propositional logic in terms of truth assignments was developed. The term tautology began to be applied to those propositional formulas that are true regardless of the truth or falsity of their propositional variables. Some early books on logic (such as Symbolic Logic by C. I. Lewis and Langford, 1932) used the term for any proposition (in any formal logic) that is universally valid. It is common in presentations after this (such as Stephen Kleene 1967 and Herbert Enderton 2002) to use tautology to refer to a logically valid propositional formula, but to maintain a distinction between tautology and logically valid in the context of first-order logic (see below).

Background

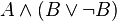

Propositional logic begins with propositional variables, atomic units that represent concrete propositions. A formula consists of propositional variables connected by logical connectives in a meaningful way, so that the truth of the overall formula can be uniquely deduced from the truth or falsity of each variable. A valuation is a function that assigns each propositional variable either T (for truth) or F (for falsity). So, for example, using the propositional variables A and B, the binary connectives  and

and  representing disjunction and conjunction respectively, and the unary connective

representing disjunction and conjunction respectively, and the unary connective  representing negation, the following formula can be obtained::

representing negation, the following formula can be obtained:: .

A valuation here must assign to each of A and B either T or F. But no matter how this assignment is made, the overall formula will come out true. For if the first conjunction

.

A valuation here must assign to each of A and B either T or F. But no matter how this assignment is made, the overall formula will come out true. For if the first conjunction  is not satisfied by a particular valuation, then one of A and B is assigned F, which will cause the corresponding later disjunct to be T.

is not satisfied by a particular valuation, then one of A and B is assigned F, which will cause the corresponding later disjunct to be T.

Definition and examples

A formula of propositional logic is a tautology if the formula itself is always true regardless of which valuation is used for the propositional variables.

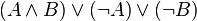

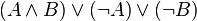

There are infinitely many tautologies. Examples include:

("A or not A"), the law of the excluded middle. This formula has only one propositional variable, A. Any valuation for this formula must, by definition, assign A one of the truth values true or false, and assign

("A or not A"), the law of the excluded middle. This formula has only one propositional variable, A. Any valuation for this formula must, by definition, assign A one of the truth values true or false, and assign  A the other truth value.

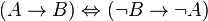

A the other truth value. ("if A implies B then not-B implies not-A", and vice versa), which expresses the law of contraposition.

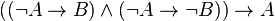

("if A implies B then not-B implies not-A", and vice versa), which expresses the law of contraposition. ("if not-A implies both B and its negation not-B, then not-A must be false, then A must be true"), which is the principle known as reductio ad absurdum.

("if not-A implies both B and its negation not-B, then not-A must be false, then A must be true"), which is the principle known as reductio ad absurdum. ("if not both A and B, then either not-A or not-B", and vice versa), which is known as de Morgan's law.

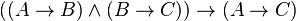

("if not both A and B, then either not-A or not-B", and vice versa), which is known as de Morgan's law. ("if A implies B and B implies C, then A implies C"), which is the principle known as syllogism.

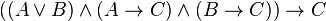

("if A implies B and B implies C, then A implies C"), which is the principle known as syllogism. (if at least one of A or B is true, and each implies C, then C must be true as well), which is the principle known as proof by cases.

(if at least one of A or B is true, and each implies C, then C must be true as well), which is the principle known as proof by cases.

A minimal tautology is a tautology that is not the instance of a shorter tautology.

is a tautology, but not a minimal one, because it is an instantiation of

is a tautology, but not a minimal one, because it is an instantiation of  .

.

Verifying tautologies

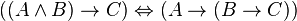

The problem of determining whether a formula is a tautology is fundamental in propositional logic. If there are n variables occurring in a formula then there are 2n distinct valuations for the formula. Therefore the task of determining whether or not the formula is a tautology is a finite, mechanical one: one need only evaluate the truth value of the formula under each of its possible valuations. One algorithmic method for verifying that every valuation causes this sentence to be true is to make a truth table that includes every possible valuation.

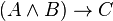

For example, consider the formula

There are 8 possible valuations for the propositional variables A, B, C, represented by the first three columns of the following table. The remaining columns show the truth of subformulas of the formula above, culminating in a column showing the truth value of the original formula under each valuation.

| A | B | C |  |

|

|

|

|

| T | T | T | T | T | T | T | T |

| T | T | F | T | F | F | F | T |

| T | F | T | F | T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | T | T | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | T | F | F | T | F | T | T |

| F | F | T | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | F | F | F | T | T | T | T |

Because each row of the final column shows T, the sentence in question is verified to be a tautology.

It is also possible to define a deductive system (proof system) for propositional logic, as a simpler variant of the deductive systems employed for first-order logic (see Kleene 1957, Sec 1.9 for one such system). A proof of a tautology in an appropriate deduction system may be much shorter than a complete truth table (a formula with n propositional variables requires a truth table with 2n lines, which quickly becomes infeasible as n increases). Proof systems are also required for the study of intuitionistic propositional logic, in which the method of truth tables cannot be employed because the law of the excluded middle is not assumed.

Tautological implication

A formula R is said to tautologically imply a formula S if every valuation that causes R to be true also causes S to be true. This situation is denoted  . It is equivalent to the formula

. It is equivalent to the formula  being a tautology (Kleene 1967 p. 27).

being a tautology (Kleene 1967 p. 27).

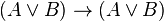

For example, let S be  . Then S is not a tautology, because any valuation that makes A false will make S false. But any valuation that makes A true will make S true, because

. Then S is not a tautology, because any valuation that makes A false will make S false. But any valuation that makes A true will make S true, because  is a tautology. Let R be the formula

is a tautology. Let R be the formula  . Then

. Then  , because any valuation satisfying R makes A true and thus makes S true.

, because any valuation satisfying R makes A true and thus makes S true.

It follows from the definition that if a formula R is a contradiction then R tautologically implies every formula, because there is no truth valuation that causes R to be true and so the definition of tautological implication is trivially satisfied. Similarly, if S is a tautology then S is tautologically implied by every formula.

Substitution

There is a general procedure, the substitution rule, that allows additional tautologies to be constructed from a given tautology (Kleene 1967 sec. 3). Suppose that S is a tautology and for each propositional variable A in S a fixed sentence SA is chosen. Then the sentence obtained by replacing each variable A in S with the corresponding sentence SA is also a tautology.

For example, let S be  , a tautology.

Let SA be

, a tautology.

Let SA be  and let SB be

and let SB be  .

It follows from the substitution rule that the sentence

.

It follows from the substitution rule that the sentence

is a tautology.

Efficient verification and the Boolean satisfiability problem The problem of constructing practical algorithms to determine whether sentences with large numbers of propositional variables are tautologies is an area of contemporary research in the area of automated theorem proving.

The method of truth tables illustrated above is provably correct – the truth table for a tautology will end in a column with only T, while the truth table for a sentence that is not a tautology will contain a row whose final column is F, and the valuation corresponding to that row is a valuation that does not satisfy the sentence being tested. This method for verifying tautologies is an effective procedure, which means that given unlimited computational resources it can always be used to mechanistically determine whether a sentence is a tautology. This means, in particular, the set of tautologies over a fixed finite or countable alphabet is a decidable set.

As an efficient procedure, however, truth tables are constrained by the fact that the number of valuations that must be checked increases as 2k, where k is the number of variables in the formula. This exponential growth in the computation length renders the truth table method useless for formulas with thousands of propositional variables, as contemporary computing hardware cannot execute the algorithm in a feasible time period.

The problem of determining whether there is any valuation that makes a formula true is the Boolean satisfiability problem; the problem of checking tautologies is equivalent to this problem, because verifying that a sentence S is a tautology is equivalent to verifying that there is no valuation satisfying  . It is known that the Boolean satisfiability problem is NP complete, and widely believed that there is no polynomial-time algorithm that can perform it. Current research focuses on finding algorithms that perform well on special classes of formulas, or terminate quickly on average even though some inputs may cause them to take much longer.

. It is known that the Boolean satisfiability problem is NP complete, and widely believed that there is no polynomial-time algorithm that can perform it. Current research focuses on finding algorithms that perform well on special classes of formulas, or terminate quickly on average even though some inputs may cause them to take much longer.

Tautologies versus validities in first-order logic

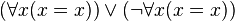

The fundamental definition of a tautology is in the context of propositional logic. The definition can be extended, however, to sentences in first-order logic (see Enderton (2002, p. 114) and Kleene (1967 secs. 17–18)). These sentences may contain quantifiers, unlike sentences of propositional logic. In the context of first-order logic, a distinction is maintained between logical validities, sentences that are true in every model, and tautologies, which are a proper subset of the first-order logical validities. In the context of propositional logic, these two terms coincide.

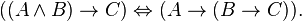

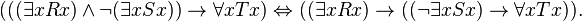

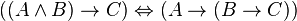

A tautology in first-order logic is a sentence that can be obtained by taking a tautology of propositional logic and uniformly replacing each propositional variable by a first-order formula (one formula per propositional variable). For example,

because  is a tautology of propositional logic,

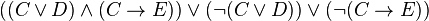

is a tautology of propositional logic,  is a tautology in first order logic. Similarly, in a first-order language with a unary relation symbols R,S,T, the following sentence is a tautology:

is a tautology in first order logic. Similarly, in a first-order language with a unary relation symbols R,S,T, the following sentence is a tautology:

It is obtained by replacing  with

with  ,

,  with

with  , and

, and  with

with  in the propositional tautology

in the propositional tautology  .

.

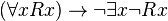

Not all logical validities are tautologies in first-order logic. For example, the sentence

is true in any first-order interpretation, but it corresponds to the propositional sentence  which is not a tautology of propositional logic.

which is not a tautology of propositional logic.

See also

Normal forms

Related logical topics

References

- Bocheński, J. M. (1959) Précis of Mathematical Logic, translated from the French and German editions by Otto Bird, Dordrecht, South Holland: D. Reidel.

- Enderton, H. B. (2002) A Mathematical Introduction to Logic, Harcourt/Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-238452-0.

- Kleene, S. C. (1967) Mathematical Logic, reprinted 2002, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-42533-9.

- Reichenbach, H. (1947). Elements of Symbolic Logic, reprinted 1980, Dover, ISBN 0-486-24004-5

- Wittgenstein, L. (1921). "Logisch-philosophiche Abhandlung", Annalen der Naturphilosophie (Leipzig), v. 14, pp. 185–262, reprinted in English translation as Tractatus logico-philosophicus, New York and London, 1922.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Tautology", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Tautology", MathWorld.

| |||||||||||||||||||