Tate–Shafarevich group

In arithmetic geometry, the Tate–Shafarevich group Ш(A/K), introduced by Lang and Tate (1958) and Shafarevich (1959), of an abelian variety A (or more generally a group scheme) defined over a number field K consists of the elements of the Weil–Châtelet group WC(A/K) = H1(GK, A) that become trivial in all of the completions of K (i.e. the p-adic fields obtained from K, as well as its real and complex completions). Thus, in terms of Galois cohomology, in can be written as

This is the author's most lasting contribution to the subject. The original notation was TS, which, Tate tells me, was intended to continue the lavatorial allusion of WC. The Americanism "tough shit" indicates the part that is difficult to eliminate.

Cassels introduced the notation Ш(A/K), where Ш is the Cyrillic letter "Sha", for Shafarevich, replacing the older notation TS.

Elements of the Tate–Shafarevich group

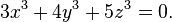

Geometrically, the non-trivial elements of the Tate–Shafarevich group can be thought of as the homogeneous spaces of A that have Kv-rational points for every place v of K, but no K-rational point. Thus, the group measures the extent to which the Hasse principle fails to hold for rational equations with coefficients in the field K. Lind (1940) gave an example of such a homogeneous space, by showing that the genus 1 curve

has solutions over the reals and over all p-adic fields, but has no rational points.

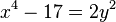

Selmer (1951) gave many more examples, such as

has solutions over the reals and over all p-adic fields, but has no rational points.

Selmer (1951) gave many more examples, such as

The special case of the Tate–Shafarevich group for the finite group scheme consisting of points of some given finite order n of an abelian variety is closely related to the Selmer group.

Shafarevich–Tate conjecture

The Tate–Shafarevich conjecture states that the Tate–Shafarevich group is finite. Rubin (1987) proved this for some elliptic curves of rank at most 1 with complex multiplication. Kolyvagin (1988) extended this to modular elliptic curves over the rationals of analytic rank at most 1. (The modularity theorem later showed that the modularity assumption always holds.)

Cassels–Tate pairing

The Cassels–Tate pairing is a bilinear pairing Ш(A)×Ш(Â)→Q/Z, where A is an abelian variety and  is its dual. Cassels (1962) introduced this for elliptic curves, when A can be identified with  and the pairing is an alternating form. The kernel of this form is the subgroup of divisible elements, which is trivial if the Tate–Shafarevich conjecture is true. Tate (1963) extended the pairing to general abelian varieties, as a variation of Tate duality. A choice of polarization on A gives a map from A to Â, which induces a bilinear pairing on Ш(A) with values in Q/Z, but unlike the case of elliptic curves this need not be alternating or even skew symmetric.

For an elliptic curve, Cassels showed that the pairing is alternating, and a consequence is that if the order of Ш is finite then it is a square. For more general abelian varieties it was sometimes incorrectly believed for many years that the order of Ш is a square whenever it is finite; this mistake originated in a paper by Swinnerton-Dyer (1967), who misquoted one of the results of Tate (1963). Poonen & Stoll (1999) gave some examples where the order is twice a square, such as the Jacobian of a certain genus 2 curve over the rationals whose Tate–Shafarevich group has order 2, and Stein (2004) gave some examples where the power of an odd prime dividing the order is odd. If the abelian variety has a principal polarization then the form on Ш is skew symmetric which implies that the order of Ш is a square or twice a square (if it is finite), and if in addition the principal polarization comes from a rational divisor (as is the case for elliptic curves) then the form is alternating and the order of Ш is a square (if it is finite).

See also

Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture

References

- Cassels, John William Scott (1962), "Arithmetic on curves of genus 1. III. The Tate–Šafarevič and Selmer groups", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society. Third Series 12: 259–296, doi:10.1112/plms/s3-12.1.259, ISSN 0024-6115, MR 0163913

- Cassels, John William Scott (1962b), "Arithmetic on curves of genus 1. IV. Proof of the Hauptvermutung", Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 211: 95–112, ISSN 0075-4102, MR 0163915

- Cassels, John William Scott (1991), Lectures on elliptic curves, London Mathematical Society Student Texts 24, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-41517-0, MR 1144763

- Hindry, Marc; Silverman, Joseph H. (2000), Diophantine geometry: an introduction, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 201, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-98981-5

- Greenberg, Ralph (1994), "Iwasawa Theory and p-adic Deformation of Motives", in Serre, Jean-Pierre; Jannsen, Uwe; Kleiman, Steven L., Motives, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-1637-0

- Kolyvagin, V. A. (1988), "Finiteness of E(Q) and SH(E,Q) for a subclass of Weil curves", Izvestiya Akademii Nauk SSSR. Seriya Matematicheskaya 52 (3): 522–540, 670–671, ISSN 0373-2436, 954295

- Lang, Serge; Tate, John (1958), "Principal homogeneous spaces over abelian varieties", American Journal of Mathematics 80: 659–684, ISSN 0002-9327, MR 0106226

- Lind, Carl-Erik (1940), "Untersuchungen über die rationalen Punkte der ebenen kubischen Kurven vom Geschlecht Eins", Thesis, University of Uppsala, 1940: 97, MR 0022563

- Poonen, Bjorn; Stoll, Michael (1999), "The Cassels-Tate pairing on polarized abelian varieties", Annals of Mathematics. Second Series 150 (3): 1109–1149, doi:10.2307/121064, ISSN 0003-486X, MR 1740984

- Rubin, Karl (1987), "Tate-Shafarevich groups and L-functions of elliptic curves with complex multiplication", Inventiones Mathematicae 89 (3): 527–559, doi:10.1007/BF01388984, ISSN 0020-9910, MR 903383

- Selmer, Ernst S. (1951), "The Diophantine equation ax³+by³+cz³=0", Acta Mathematica 85: 203–362, doi:10.1007/BF02395746, ISSN 0001-5962, MR 0041871

- Shafarevich, I. R. (1959), "The group of principal homogeneous algebraic manifolds", Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR (in Russian) 124: 42–43, ISSN 0002-3264, MR 0106227 English translation in his collected mathematical papers

- Stein, William A. (2004), "Shafarevich-Tate groups of nonsquare order", Modular curves and abelian varieties, Progr. Math. 224, Basel, Boston, Berlin: Birkhäuser, pp. 277–289, MR 2058655

- Swinnerton-Dyer, P. (1967), "The conjectures of Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer, and of Tate", in Springer, Tonny A., Proceedings of a Conference on Local Fields (Driebergen, 1966), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 132–157, MR 0230727

- Tate, John (1958), WC-groups over p-adic fields, Séminaire Bourbaki; 10e année: 1957/1958 13, Paris: Secrétariat Mathématique, MR 0105420

- Tate, John (1963), "Duality theorems in Galois cohomology over number fields", Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians (Stockholm, 1962), Djursholm: Inst. Mittag-Leffler, pp. 288–295, MR 0175892

- Weil, André (1955), "On algebraic groups and homogeneous spaces", American Journal of Mathematics 77: 493–512, ISSN 0002-9327, MR 0074084