Tankerville Chamberlayne

Tankerville Chamberlayne (9 August 1843 – 17 May 1924)[1] was a landowner in Hampshire and a member of parliament, serving the Southampton constituency three times, as an Independent and Conservative. Following the 1895 General Election false allegations were made concerning his conduct and this resulted in his being unseated on a technicality.[2] He subsequently raised the question of false electioneering statements in Parliament.[3]

He was a member of the Carlton Club and the Royal Thames Yacht Club and a Justice of the Peace for Hampshire, as well as being Lord of the Manors of Hound, North Baddesley,[4] Woolston and Barton Peveril (near Eastleigh) in Hampshire and East Norton in Leicestershire.[2]

Early life and education

Chamberlayne was born at Pangbourne, Berkshire, the second son of Thomas Chamberlayne (1805–1876) and Amelia (née Onslow).[5] He was educated at Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford, where he took his BA in 1865.[2]

Ancestry

Chamberlayne was descended from Count John de Tankerville who came over to England from Normandy with William the Conqueror.[6] The de Tankerville family home was the castle at Tancarville near Le Havre.

Count John's family were the hereditary chamberlains to the Dukes of Normandy and he became chamberlain to King Henry I; his son Richard held the same office under King Stephen and assumed the surname "Chamberlayne".[6]

His great uncle William Chamberlayne (1760–1829) was Member of Parliament for Southampton from 1818 until his death. Whilst serving the town, William Chamberlayne was also chairman of the company supplying gas lighting to the town of Southampton and donated the iron columns for the new gas street-lights. In 1822, the townspeople erected a memorial consisting of an iron Doric column; this now stands in Houndwell Park, near the city centre.[7]

Tankerville's father, Thomas (1805–1876) was a keen yachtsman who sailed his yacht, Arrow, in the inaugural America's Cup race in 1851. He also played cricket for Hampshire and was a great hunting and coursing enthusiast, who built both new stables and a cricket pitch at the family home at Cranbury Park near Winchester.[5]

Tankerville's mother, Amelia, was the daughter of Denzil Onslow (1770–1838), a General in the Grenadier Guards and an amateur cricketer.[5]

Their first son, Denzil, became a captain in the 13th Light Dragoons, serving with distinction in the Crimean War, where he took part in the charge at Balaclava in 1854.[8][9] Denzil died in 1873, leaving no heir, so on the death of Thomas in 1876, Tankerville succeeded his father.[5]

At this time, the Chamberlayne family estates included the estate at Cranbury Park in the Parish of Hursley and the Weston Grove estate in Southampton which included the abbey at Netley. Chamberlayne resided at Weston Grove until after he retired from politics in 1906.[10]

Political career

Chamberlayne was first elected as Member of Parliament for Southampton at the 1892 General Election, when he headed the poll with 5449 votes.[2] He replaced the previous Conservative representative, Alfred Giles who was retiring from politics; his fellow M.P. for the town was Francis Evans, of the Liberal Party.

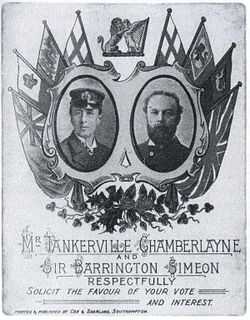

At the 1895 General Election he stood for re-election on a joint ticket with Sir John Barrington Simeon of the Liberal Unionist Party. Although he regained his seat, the election was subsequently declared invalid because his agent had loaned a constituent money for a railway fare.[2]

However, in a debate in Parliament on 5 May 2004, Alan Whitehead, the M.P. for Southampton Test, who was discussing electoral fraud, repeated unsubstantiated allegations made in 1895:"There is scant evidence of widespread fraud and personation in England, Scotland and Wales in recent years. That has not always been the case: in Victorian times, there was widespread evidence of personation and electoral corruption, with people receiving funds to vote. The Conservative candidate in the 1895 election in Southampton, Sir (sic) Tankerville Chamberlayne, gave his address as the first floor of the Dolphin Hotel in central Southampton. Six strong men carried him shoulder-high from the first floor and placed him in a cart that they had previously unhorsed. They then pulled him to the Cowherds Inn at Above Bar, and he waved to the crowds and threw sovereigns at them as he went. Incidentally, his election was ruled invalid, and a further election was held. These days, however, we have relatively clean and uncorrupt elections in the UK, and there is certainly little evidence of personation, fraud, undue influence, bribery and treating in our electoral system."[11]In reality, the case was somewhat less spectacular:

'All kinds of charges of general “treating” of electors were laid at his door, but they were completely exploded at a special hearing – all except one case of a Southampton elector who was at Winchester at the time and to whom he lent two shillings for his fare to get him to Southampton to vote. So on that one issue Mr Tankerville Chamberlayne was unseated – but he returned triumphant a few years later to represent Southampton Borough for another period of years'.[2]

A by-election was held on 22 February 1896, some six months after the General Election. At the by-election, Chamberlayne lost his seat back to Francis Evans, but he was returned in the 1900 general election. He was defeated at the 1906 general election by William Dudley Ward and Sir Ivor Philipps of the Liberal Party.[12]

Although he stood for re-election in the 1910 general election, he was unsuccessful and his political career was over.[13]

Sporting interests

Chamberlayne was a keen sportsman and took an active interest in many sports, including cricket, rugby, football, fox hunting and yachting.[2] He had a reputation for being very generous to the many sporting organisations who had claims on his patronage, although he did not actively involve himself with day-to-day details.[14]

Cricket

He is recorded as having played in two major cricket matches.[15] The first was in July 1862 at Day's (Antelope) Ground, Southampton (which his father Thomas had helped to finance). In this match, Chamberlayne played for the Gentlemen of Hampshire against a United England Eleven. The Hampshire gentlemen fielded 22 players, including Thomas Chamberlayne, with Tankerville contributing just six runs in two innings. Despite their numerical inferiority (only fielding eleven players), the United England Eleven won the match by 64 runs.[16]

He helped to finance a cricket ground[17] at Yatton in Somerset[13] and appeared there in the opening match in July 1879, when he played for the Gentlemen of Somerset against the Gentlemen of Hampshire. The match was curtailed because of inclement weather, but this did not prevent those present from enjoying the supper and fireworks that Chamberlayne laid on following the match.[18]

The only other major cricket match played at Yatton was in August 1887, when the Gentlemen of Gloucestershire entertained a touring team from Canada. The Gloucestershire gentlemen included W. G. Grace in their eleven with the match ending in a draw at the end of the second day.[19]

Football

Although he never played football, he became very interested in the game as it increased in popularity. In 1884, he became President of the Trojans club in Eastleigh, having been Vice-President for some years previously; he remained president of the Trojans until his death in 1924.[2]

He was also President of the Freemantle Football Club and helped them financially by paying the rent (£24 per annum) on their ground in Freemantle. Following the failure of proposals to merge Freemantle with its neighbour, Southampton F.C. in 1897, Chamberlayne was invited to become a shareholder and director of the Southampton club. Although he accepted the offer, there is no record of him attending a meeting of either the board or of the shareholders.[14]

Yachting

_1889.jpg)

Chamberlayne regularly sailed his father's yacht, the Arrow, which had taken part in the inaugural America's Cup race in 1851. In 1885, he had his own steam yacht, the Amazon, built at the "Arrow Yard" in Southampton; this yacht is still sailing (in private hands) and is listed on the National Historic Ships Register.[20][21] In 1904, the Arrow Yard was sold to the neighbouring yard of Fay & Company, which was later absorbed by Camper and Nicholsons in 1912.[22]

Public benefactor

Chamberlayne was a generous supporter of various activities and causes. In 1897, to mark Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee he donated the recreation ground at Netley, near Southampton to the village.[22] He and his wife also gave a party for the schoolchildren of Woolston at Weston Grove House.[23]

As Lord of the Manor, he funded the restoration of the chapel at the Leicestershire village of East Norton.[24]

In 1904, he donated land at Hursley Road, Chandler's Ford for the building of St. Boniface Church, laying the foundation stone on 1 April 1904.[25]

In 1922, he transferred the ruins of Netley Abbey into the care of the Ministry of Works.[22]

Later life

Chamberlayne continued to live at Weston Grove after his political career had ended although he later moved to the family home at Cranbury Park, near Hursley outside Winchester.[26]

In 1909, an Act of Parliament required that Chamberlayne sell 189 acres (76 ha) of land in Weston to the London and South Western Railway for the purpose of building an enormous dry dock some 1,600 ft long (490 m). Although the land was acquired, the project was never undertaken;[27] the site was subsequently sold to the Ministry of Munitions and the Rolling Mills were built instead.[28] Situated directly below Weston Grove House, the Rolling Mills building obstructed the view of Southampton Water from the house, which was demolished in 1940.[29]

He was married to Edith; their son, Thomas Edmund Onslow Chamberlayne, was killed on 18 August 1916 at the Battle of the Somme.[30] He is remembered on the war memorial at North Baddesley in Hampshire.[31][32]

Chamberlayne died in 1924 and was succeeded by his daughter, Penelope Mary Alexandra Chamberlayne, who married Major Nigel Donald Peter Macdonald (son of Sir Godfrey Middleton Bosville Macdonald of the Isles (15th Baronet)), changing their surname to "Chamberlayne-Macdonald".[33] The family are still resident at Cranbury Park. Penelope is a Patroness of the Royal Caledonian Ball.[34]

Legacy

Several streets in Southampton and Eastleigh are named after Chamberlayne and his family. These include Tankerville Road in Woolston and Chamberlayne Road in Eastleigh. There was also the former Tankerville School in Eastleigh and the present-day Chamberlayne College for the Arts in the Weston area. There are Cranbury Roads in both Sholing and Eastleigh, as well as Cranbury Place, Cranbury Avenue, Onslow Road and Denzil Avenue in the Bevois Valley area of Southampton.[22]

References

- ↑ "Southampton Parliamentary constituency". Leigh Rayment. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 "Trojans Football Club: The Early Presidents". Trojans Rugby Club. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Hansard".

- ↑ Smith, Sandra J. (2003). "Kelly's Directory of Hampshire, 1899". Kelly's Directory. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Leonard, A.G.K. (1984). Stories of Southampton Streets. Paul Cave Publications. pp. 72 & 74. ISBN 0-86146-041-3.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Stories of Southampton Streets. p. 68.

- ↑ "William Chamberlayne Gas Column". Houndwell Park. Southampton City Council. 28 November 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ Yonge, Charlotte M. "John Keble's Parishes: The Golden Days of Hursley". www.online-literature.com. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Cornet Denzil Chamberlayne – 13th Light Dragoons". Lives of The Light Brigade. www.chargeofthelightbrigade.com. 27 May 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Stories of Southampton Streets. p. 76.

- ↑ "Electoral Register (debate in Westminster Hall)". Hansard. www.parliament.uk. 5 May 2004. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Members of the House of Commons – Southampton". www.leighrayment.com. 21 June 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "From the Mercury, 20 March 1909". www.thisissomerset.co.uk. 20 March 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Juson, Dave; Bull, David (2001). Full-Time at The Dell. Hagiology. p. 43. ISBN 0-9534474-2-1.

- ↑ "Tankerville Chamberlayne (cricket career summary)". cricketarchive. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Gentlemen of Hampshire v United England Eleven, July 1862 (scorecard)". cricketarchive. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Tankerville Chamberlayne's Ground, Yatton". cricketarchive. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Gentlemen of Somerset v Gentlemen of Hampshire, July 1879 (scorecard)". cricketarchive. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Gentlemen of Gloucestershire v Gentlemen of Canada, August 1887 (scorecard)". cricketarchive. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Amazon: Certificate No. 563". National Historic Ships Register. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Motor Yacht "Amazon"". www.superyachttimes.com. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Stories of Southampton Streets. p. 74.

- ↑ "Peartree Church Walk". www.diaperheritage.com. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "East Norton Church History: Notes on some architectural features". www.leicestershirevillages.com. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Hegan, Margot (1993). "The History of St Boniface and St Martin in the Wood". Parish of Chandler's Ford. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ↑ Lundy, Darryl (15 May 2005). "Tankerville Chamberlayne". www.thepeerage.com. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone Publications. p. 137. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ↑ Southampton. An Illustrated History. pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Brown, Jim (2002). The Illustrated History of Southampton's Suburbs. Breedon Books. ISBN 1-85983-405-1.

- ↑ "Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Casualty Details". CWGC. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Smith, Sandra J. (2003). "North Baddesley: The War Memorial". homepage.ntlworld.com. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "North Baddesley village website: The War Memorial". www.northbaddesleyvillage.co.uk. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Lundy, Darryl (9 October 2006). "Major Nigel Donald Peter Chamberlayne-Macdonald". www.thepeerage.com. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Patronesses". Royal Caledonian Ball. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Tankerville Chamberlayne

- Hansard report on 2001 speech by Alan Whitehead M.P. with a slightly different version of the 1895 election

- Hansard report on 2008 speech by Alan Whitehead M.P.

- Report of the 2008 speech on Alan Whitehead's website

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Francis Henry Evans Alfred Giles |

Member of Parliament for Southampton 1892–1896 With: Sir Francis Henry Evans to 1895 Sir John Simeon from 1895 |

Succeeded by Sir John Simeon, Bt Sir Francis Henry Evans |

| Preceded by Sir John Simeon, Bt Sir Francis Henry Evans |

Member of Parliament for Southampton 1900–1906 With: Sir John Simeon |

Succeeded by Sir Ivor Philipps William Dudley Ward |

|