Talimogene laherparepvec

| |

|---|---|

| Transmission electron micrograph of an unmodified herpes simplex virus | |

| Clinical data | |

| Pregnancy cat. | TBD |

| Legal status | Investigational |

| Routes | Injection |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 1187560-31-1 |

| ATC code | ? |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | JS1 34.5-hGMCSF 47- pA- |

Talimogene laherparepvec (tal im' oh jeen la her" pa rep' vek), often simply called "T-VEC" is a cancer-killing (oncolytic) virus currently being studied for the treatment of melanoma and other advanced cancers. The drug was initially developed by BioVex, Inc. under the name OncoVEXGM-CSF until it was acquired by Amgen in 2011.[1] With the announcement of positive results in March 2013, T-VEC is the first oncolytic virus to be proven effective in a Phase III clinical trial.[2]

Mechanism of action

T-VEC was engineered from herpes simplex 1 (HSV-1), a relatively innocuous virus that normally causes cold sores. A number of genetic modifications were made to the virus in order to:

- Attenuate the virus (so it can no longer cause herpes)

- Increase selectivity for cancer cells (so it destroys cancer cells while leaving healthy cells unharmed)

- Secrete the cytokine GM-CSF (a protein naturally secreted in the body to initiate an immune response)

| Modification | Result |

|---|---|

| Use of new HSV-1 strain (JS1) | Improved tumor cell killing ability compared with other strains |

| Deletion of ICP34.5 | Prevents HSV infection of non-tumor cells, providing tumor-selective replication |

| Deletion of ICP47 | Enables antigen presentation |

| Earlier insertion of US11 | Increases replication and oncolysis of tumor cells |

| Insertion of human GM-CSF gene | Enhances anti-tumor immune response by recruiting and stimulating dendritic cells to tumor site |

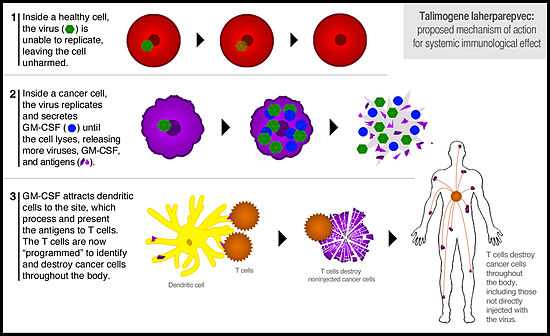

T-VEC has a dual mechanism of action, destroying cancer both by directly attacking cancer cells and also by helping the immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells. T-VEC is injected directly into a number of a patient’s tumors. The virus invades both cancerous and healthy cells, but it is unable to replicate in healthy cells and thus they remain unharmed. Inside a cancer cell, the virus is able to replicate, secreting GM-CSF in the process. Eventually overwhelmed, the cancer cell lyses (ruptures), destroying the cell and releasing new viruses, GM-CSF, and an array of tumor-specific antigens (pieces of the cancer cell that are small enough to be recognized by the immune system).[5]

The GM-CSF attracts dendritic cells to the site. Dendritic cells are immune cells that process and present antigens to the immune system so that the immune system can then identify and destroy whatever produced the antigen. The dendritic cells pick up the tumor antigens, process them, and then present them on their surface to cytotoxic (killer) T cells. Now the T cells are essentially "programmed" to recognize the cancer as a threat. These T cells lead an immune response that seeks and destroys cancer cells throughout the body (eg, tumors and cancer cells that were not directly injected with T-VEC).[6][7]

In this way, T-VEC has both a direct effect on injected tumors and a systemic effect throughout the entire body.[8] Because the adaptive immune system “remembers” a target once it has been identified, there is high likelihood that the effect of an oncolytic virus like T-VEC will be durable (eg, prevent relapse). And it is for this reason that T-VEC does not need to be injected into every tumor, just a few in order to start the immune process.

Efficacy in melanoma

Clinical efficacy in unresectable melanoma has been demonstrated in Phase II and Phase III clinical trials.

The Phase II clinical trial was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2009. 50 patients with advanced melanoma (most of whom had failed previous treatment) were treated with T-VEC. The overall response rate (patients with a complete or partial response per RECIST criteria) was 26% (16% complete responses, 10% partial responses). Another 4% of patients had a surgical complete response, and another 20% had stable disease for at least 3 months. On an extension protocol, 3 more patients achieved complete responses, and overall survival was 54% at 1 year and 52% at 2 years—demonstrating that responses to T-VEC are quite durable.[9]

Consistent with other immunotherapies, some patients exhibited initial disease progression before responding to therapy because of the time it takes to generate the full immune response. Responses were seen in both injected and uninjected tumors (including those in visceral organs), demonstrating the systemic immunotherapeutic effect of T-VEC. Treatment was extremely well tolerated, with only Grade 1 or 2 drug-related side effects, the most common being mild flu-like symptoms.[10]

|

|

Amgen announced the initial results of the Phase III OPTiM trial on Mar. 19, 2013. This global, randomized, open-label trial compared T-VEC with subcutaneously administered GM-CSF (2:1 randomization) in 430 patients with unresectable stage IIIB, IIIC or IV melanoma. The primary endpoint was durable response rate (DRR), defined as a complete or partial tumor response lasting at least 6 months and starting within 12 months of treatment.[11]

T-VEC was proven to offer superior benefits in metastatic melanoma. DRR was achieved in 16% of patients receiving T-VEC compared with only 2% in the GM-CSF control group (P<.0001). The greatest benefit was seen in patient with stage IIIB or IIIC melanoma, with a 33% DRR vs 0% with GM-CSF. The objective response rate (any response) with T-VEC was 26%, with an impressive 11% of patients experiencing a complete response (complete disappearance of melanoma throughout the body). This demonstrated once again that T-VEC has a systemic immune effect that destroys distant, uninjected tumors.[12] According to Financial Times one of the investigators involved questioned the ethics of the trial design, as the control arm received subcutaneous GM-CSF instead of standard care [13]

A trend toward improved survival with T-VEC was observed in a pre-specified interim analysis of this endpoint, with the final survival data (event-driven) expected in late 2013. At the interim analysis, T-VEC was associated with a 21% reduced risk of death. The most common side effects with T-VEC were fatigue, chills, and fever. No serious side effect occurred in more than 3% of patients in either arm of the study.[14]

The investigators concluded that “T-VEC represents a novel potential [treatment] option for melanoma with regional or distant metastases.”[15] The success of T-VEC in the OPTiM trial represents the first Phase III proof of efficacy for a virus-based oncolytic immunotherapy.

Efficacy in head and neck cancer

Clinical efficacy in squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (SCCHN) has been demonstrated in a Phase II trial, and a Phase III trial was started but terminated without explanation.[16]

The Phase II trial results were announced at ASCO in 2009 and published in Clinical Cancer Research in 2010. 17 patients with stage III or IVA SCCHN received one of 4 different doses of T-VEC along with concomitant cisplatin and radiotherapy. 93% of patients had a pathological complete response confirmed by neck resection. 82% of patients had a complete or partial radiologic response per RECIST criteria. The remaining patients had stable disease, with no patient (0%) experiencing disease progression. At the median post-treatment follow-up of 29 months, all (100%) patients continued to show loco-regional control with disease-specific survival at 82%. T-VEC was well tolerated and had a similar safety profile to that seen in the melanoma trials (Grade 1 or 2 side effects only, the most common being mild flu-like symptoms). 77% of patients remained relapse-free as of 2010.[17][18]

A Phase III trial in SCCHN was initiated by BioVEX in 2010.[19] After Amgen acquired T-VEC in 2011, they halted the trial due to the "changing therapeutic landscape for patients with SCCHN"— presumably the discovery of HPV status as a major prognostic risk factor in SCCHN.[20]

Efficacy in other cancers

Clinical activity has been observed in Phase I studies including patients with pancreatic, breast, and colorectal cancers.[21][22] Because it is an immunoresponsive tumor, renal cell carcinoma is also a potential target for oncolytic immunotherapy.[23]

Tolerability

T-VEC has generally been very well tolerated, with the vast majority of adverse events being mild or moderate (Grade 1 or 2). The most common side effects are mild fatigue, chills, or fever. In the Phase III OPTiM trial, the most common serious side effect was cellulitis, reported in only 2.1% of patients.[24][25][26]

See also

References

- ↑ Bloomberg News. (2011, January 24). Amgen buys a cancer drug maker. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com. Available here

- ↑ Amgen press release. Amgen announces top-line results of phase 3 talimogene laherparepvec trial in melanoma. Mar 19, 2013. Available here

- ↑ Liu BL, Robinson M, Han Z-Q, et al. ICP34.5 deleted herpes simplex virus with enhanced oncolytic, immune stimulating, and anti-tumour properties. Gene Therapy. 2003;10:292–303 . Available here

- ↑ Senzer NN, Kaufman HL, Amatruda T, et al. Phase II clinical trial of a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor–encoding, second-generation oncolytic herpesvirus in patents with unresectable metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5763-5771. Available here

- ↑ Liu BL, Robinson M, Han Z-Q, et al. ICP34.5 deleted herpes simplex virus with enhanced oncolytic, immune stimulating, and anti-tumour properties. Gene Therapy. 2003;10:292–303 . Available here

- ↑ Liu BL, Robinson M, Han Z-Q, et al. ICP34.5 deleted herpes simplex virus with enhanced oncolytic, immune stimulating, and anti-tumour properties. Gene Therapy. 2003;10:292–303 . Available here

- ↑ Kaufman HL, Kim DW, DeRaffele G, Mitcham J, Coffin RS, Kim-Schulze S. Local and distant immunity induced by intralesional vaccination with an oncolytic herpes virus encoding GM-CSF in patients with stage IIIc and IV melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(3):718-30. Available here

- ↑ Núñez MA. Tumor killer viruses. Mapping Ignorance. January 9, 2013. Available here

- ↑ Senzer NN, Kaufman HL, Amatruda T, et al. Phase II clinical trial of a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor–encoding, second-generation oncolytic herpesvirus in patents with unresectable metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5763-5771. Available here

- ↑ Senzer NN, Kaufman HL, Amatruda T, et al. Phase II clinical trial of a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor–encoding, second-generation oncolytic herpesvirus in patents with unresectable metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5763-5771. Available here

- ↑ Amgen press release. Amgen announces top-line results of phase 3 talimogene laherparepvec trial in melanoma. Mar 19, 2013. Available here

- ↑ Andtbacka RHI, Collichio FA, Amatruda T et al. OPTiM: A randomized phase III trial of talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) versus subcutaneous (SC) granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) for the treatment (tx) of unresected stage IIIB/C and IV melanoma. J Clin Oncol 31, 2013 (suppl; abstr LBA9008). Available here

- ↑ http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/24b5634e-f2e4-11e1-8577-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2idyuAroh

- ↑ Andtbacka RHI, Collichio FA, Amatruda T et al. OPTiM: A randomized phase III trial of talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) versus subcutaneous (SC) granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) for the treatment (tx) of unresected stage IIIB/C and IV melanoma. J Clin Oncol 31, 2013 (suppl; abstr LBA9008). Available here

- ↑ Andtbacka RHI, Collichio FA, Amatruda T et al. OPTiM: A randomized phase III trial of talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) versus subcutaneous (SC) granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) for the treatment (tx) of unresected stage IIIB/C and IV melanoma. J Clin Oncol 31, 2013 (suppl; abstr LBA9008). Available here

- ↑ ClinicalTrials.gov. Study of safety and efficacy of OncoVEXGM-CSF With cisplatin for treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer. NLM Identifier: NCT01161498. Available here.

- ↑ Harrington K, Hingorani M, Tanay M, et al. A phase I/II dose escalation study of OncoVexGM-CSF and chemoradiotherapy in untreated stage III/IV squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s(suppl; abstr 6018). Available here

- ↑ Harrington K, Hingorani M, Tanay M, et al. Phase I/II study of oncolytic HSVGM-CSF in combination with radiotherapy and cisplatin in untreated stage III/IV squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4005-4015. Available here

- ↑ ClinicalTrials.gov. Study of safety and efficacy of OncoVEXGM-CSF With cisplatin for treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer. NLM Identifier: NCT01161498. Available here.

- ↑ Amgen press release. Amgen's second quarter 2011 revenue increased 4 percent to $4.0 billion. Jul 29, 2011. Available here.

- ↑ Chang KJ, Senzer NN, Binmoeller K, Goldsweig H, Coffin R. Phase I dose-escalation study of talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) for advanced pancreatic cancer (ca). J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl; abstr e14546). Available here

- ↑ Hu JCC, Coffin RS, Davis CJ, et al. A phase I study of OncoVEXGM-CSF, a second-generation oncolytic herpes simplex virus expressing granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6737-6747. Available here

- ↑ American Cancer Society. Kidney cancer (adult) - renal cell carcinoma: What's new in kidney cancer research and treatment? Last revised: 1/18/2013. Available here

- ↑ Senzer NN, Kaufman HL, Amatruda T, et al. Phase II clinical trial of a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor–encoding, second-generation oncolytic herpesvirus in patents with unresectable metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5763-5771. Available here

- ↑ Harrington K, Hingorani M, Tanay M, et al. Phase I/II study of oncolytic HSVGM-CSF in combination with radiotherapy and cisplatin in untreated stage III/IV squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4005-4015. Available here

- ↑ Andtbacka RHI, Collichio FA, Amatruda T et al. OPTiM: A randomized phase III trial of talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) versus subcutaneous (SC) granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) for the treatment (tx) of unresected stage IIIB/C and IV melanoma. J Clin Oncol 31, 2013 (suppl; abstr LBA9008). Available here