Taiwanese Hokkien

| Taiwanese Hokkien | |

|---|---|

|

臺灣話 / 臺語 Tâi-oân-oē / Tâi-gí | |

| Native to | Taiwan |

Native speakers | 15 million Hokkien (Hoklo) in Taiwan (1997)[1] |

| Latin (pe̍h-ōe-jī), Hanji | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | None, de facto status in Taiwan since it is one of the statutory languages for public transport announcements in Taiwan.[2] |

| Regulated by | National Languages Committee (Ministry of Education, ROC). |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| |

Taiwanese Hokkien (Chinese: 臺灣閩南語; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tâi-oân Bân-lâm-gí; Tâi-lô: Tâi-uân Bân-lâm-gí), commonly known as Taiwanese (Tâi-oân-oē 臺灣話 or Tâi-gí 臺語), is the Hokkien dialect of Min Nan as spoken by about 70% of the population of Taiwan.[3] The largest linguistic group in Taiwan, in which Hokkien is considered a native language, is known as Hoklo or Holo. The correlation between language and ethnicity is generally true, though not absolute, as some Hoklo speak Hokkien poorly while some non-Hoklo speak Hokkien fluently. Pe̍h-ōe-jī (POJ) is a popular orthography for this variant of Hokkien.

Taiwanese Hokkien is generally similar to Amoy. Minor differences only occur in terms of vocabulary. Like Amoy, Taiwanese Hokkien is based on a mixture of Zhangzhou and Quanzhou speech. Due to the mass popularity of Hokkien entertainment media from Taiwan, Taiwanese Hokkien has grown to become the more influential Hokkien dialect of Min Nan, especially since the 1980s. Along with Amoy, the Taiwanese prestige dialect (based on the Tâi-lâm variant) is regarded as "standard Hokkien".

Classification

Taiwanese Hokkien is a variant of Min Nan, closely related to the Amoy dialect. It is often seen as a Chinese dialect within the larger Sinitic language family. On the other hand, it may also be seen as an independent language since it is not mutually intelligible with Standard Chinese. As with most “language/dialect” distinctions, how one describes Taiwanese depends largely on one's personal views (see the article “varieties of Chinese”).

Some scholars claim Min is the only branch of Chinese that cannot be directly derived from Middle Chinese,[4] whereas others argue that Min Nan (Hokkien dialect) can trace its roots through the Tang Dynasty.[citation needed] Some Min Nan vocabulary is not derived from Chinese and does not have corresponding Chinese characters. This contributes to the mutual unintelligibility with spoken Mandarin or other Chinese dialects.[citation needed]

There is both a colloquial version and a literary version of Taiwanese Hokkien. Spoken Taiwanese Hokkien is almost identical to spoken Amoy Hokkien. Regional variations within Taiwanese may be traced back to Hokkien variants spoken in Southern Fujian (Quanzhou and Zhangzhou). Taiwanese Hokkien also contains loanwords from Japanese and the Formosan languages. Recent work by scholars such as Ekki Lu, Sakai Toru, and Lí Khîn-hoāⁿ (also known as Tavokan Khîn-hoāⁿ or Chin-An Li), based on former research by scholars such as Ông Io̍k-tek, has gone so far as to associate part of the basic vocabulary of the colloquial Taiwanese with the Austronesian and Tai language families; however, such claims are controversial.

The literary form of Minnan once flourished in Fujian and was brought to Taiwan by early emigrants. Tale of the Lychee Mirror (Nāi-kèng-kì), a manuscript for a series of plays published during the Ming Dynasty in 1566, is one of the earliest known works. This form of the language is now largely extinct. However, literary readings of the numbers are used in certain contexts such as reciting telephone numbers (see Literary and colloquial readings of Chinese characters).

History and formation

Spread of Hokkien to Taiwan

During Yuan dynasty, Quanzhou became a major international port for trade with the outside world.[5] From that period onwards, due to political and economic reasons, many people from regions of Min Nan (southern Fujian) started to emigrate overseas. This included the relatively undeveloped Taiwan, starting around 1600. They brought with them their native language, Hokkien.

During the late Ming dynasty, due to political chaos, there was increased migration from southern Fujian and eastern Guangdong to Taiwan. The earliest immigrants who were involved in the land development of Taiwan included Yan Siqi (顏思齊) and Zheng Zhilong (鄭芝龍). In 1622, Yan Siqi and his forces occupied Bengang 笨港 (today's Beigang town 北港鎮 in Yunling county) and started to develop Chu-lô-san (諸羅山, today's Chiayi city). After the death of Yan, his power was inherited by Zheng Zhilong and he ruled the Straits of Taiwan. In 1628, Zheng Zhilong accepted the bureaucratic rule by Ming court.[6]

During the reign of Chongzhen Emperor, there were frequent droughts in the Fujian region. Zheng Zhilong suggested to Xiong Wencan (熊文燦, governor of Fujian) to mass tens of thousands of people and to give each person 3 taels and three persons one buffalo, in order to attract them to go to Taiwan to develop the agriculture in Taiwan. Although there were many people who returned home after the development, a portion of the people settled down permanently in Taiwan. They also traded and intermarried with many Taiwanese aborigines (in particular the Siraya people) and propagated the Hokkien dialect around Taiwan.

Development and divergence

In 1624 and 1626, the Dutch and Spanish dispatched large forces to occupy Tainan and Keelung respectively. During the 40 years of Dutch colonial rule of Taiwan, many Han Chinese from the Quanzhou, Zhangzhou and Hakka regions of mainland China were recruited to help develop Taiwan. Because of intermingling with Siraya people as well as Dutch colonial rule, the Hokkien dialects started to deviate from the original Hokkien spoken in mainland China.

In 1661, Koxinga dispatched a large troop to attack Taiwan. He managed to conquer Taiwan and chased the Dutch out, thus establishing the Koxinga dynasty. Koxinga originated from Quanzhou. Chen Yonghua (陳永華), who was in charge of establishing the education system of Koxinga dynasty, also originated from Quanzhou. Because most of the soldiers he brought to Taiwan came from Quanzhou, Taiwan had once held Quanzhou Hokkien as its prestige dialect during that time.

In 1683, Shi Lang attacked Taiwan and caused the Koxinga dynasty to collapse. The Qing dynasty officially began to rule Taiwan. In the following years, in order to prevent people from rebelling, the Qing court instituted a ban on migration to Taiwan, especially the migration of Hakka people from Guangdong province, which led Hokkien to become a prestige language in Taiwan. During the reigns of the Yongzheng Emperor and the Qianlong Emperor, the restriction began to be relaxed. In 1874, the ban on emigration to Taiwan was removed.

In the first decades of the 18th century, the language difference between the Chinese Qing imperial bureaucrats and the commoners was recorded by the first Imperial High Commissioner to Taiwan (1722), Huáng Shújǐng, a Mandarin Chinese-speaker sent by the Kangxi Emperor, during whose reign Taiwan was annexed in 1684:

| “ | In this place, the language is as birdcall – totally unintelligible! For example: for the surname Liú, they say ‘Lâu’; for Chén, ‘Tân’; Zhuāng, ‘Chng’; and Zhāng is ‘Tioⁿ’. My deputy’s surname Wú becomes ‘Ngô͘’. My surname Huáng does not even have a proper vowel: it is ‘N̂g’ here! It is difficult to make sense of this. (郡中鴃舌鳥語全不可曉如劉呼澇陳呼澹莊呼曾張呼丟余與吳待御兩姓吳呼作襖黃則無音厄影切更為難省) |

” |

| —Records from the mission to Taiwan and its Strait, Volume II: On the area around Fort Provintia, Tainan (臺海使槎錄 卷二 赤嵌筆談) | ||

This set the tone for the uneasy relationship between this language community and the colonial establishments in the next few centuries.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, civil unrest and armed conflicts were frequent in Taiwan. In addition to resistance against the government (both Chinese and Japanese), battles between ethnic groups were also significant: the belligerent usually grouped around the language they use. History recorded battles between the Hakka and the Taiwanese-language speakers; between these and the aborigines; and between those who spoke the Choân-chiu variant of what became the Taiwanese language and those who spoke the Chiang-chiu variant.

During the 200 years of Qing dynasty's rule of Taiwan, Min Nan people who migrated to Taiwan began to increase rapidly. In particular, most of them came from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou. With increasing migration, the Hokkien dialect was also spread to every part of Taiwan. Although there was a conflict between Quanzhou and Zhangzhou people in Taiwan historically, the intermingling of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou people caused the two Hokkien accents to be mixed together. Apart from Yilan and Lugang, which still preserves the original Zhangzhou and Quanzhou accents respectively, every region of Taiwan speaks a variant of Hokkien based on a mixture of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou Hokkien. Scholars such as Ang Ui-jin called Taiwanese Hokkien a mix or combination of both Quanzhou and Zhangzhou Hokkien (漳泉濫).[7]

After 1842, Amoy became an important port in mainland China and became the only port opened for trade in the Min Nan region. Amoy Hokkien was also formed from a mix of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou Hokkien, and gradually replaced Quanzhou Hokkien as the prestige dialect.[8] During the Japanese colonial rule of Taiwan, Taiwan began to hold Amoy Hokkien as its standard pronunciation and was known as Taiwanese by the Japanese.[9] However, after 1945, Amoy Hokkien and Taiwanese Hokkien began to have some minor differences due to different development and evolution in the two languages.

Modern times

Later, in the 20th century, the conceptualization of Taiwanese is more controversial than most variations of Chinese because at one time it marked a clear division between the Mainlanders who arrived in 1949 and the pre-existing majority native Taiwanese. Although the political and linguistic divisions between the two groups have blurred considerably, the political issues surrounding Taiwanese have been more controversial and sensitive than for other variants of Chinese.

After the First Sino-Japanese War, due to military defeat to the Japanese, the Qing dynasty ceded Taiwan to Japan, causing the contacts with the Min Nan regions of mainland China to stop. During the Japanese colonial rule, Japanese language became an official language in Taiwan. Taiwanese Hokkien began to absorb large number of Japanese loan words into its language. Examples of Japanese loan words (some which had in turn been borrowed from English) used in Taiwanese include piān-só͘ (便所) for “toilet”, pêⁿ (坪) for a Japanese unit of land, ka-suh (ガス) for “gas”, o͘-tó͘-bái (オートバイ “autobike”) for “motorcycle”. All of these caused Taiwanese to deviate from Hokkien in mainland China.

During Kōminka of the late Japanese colonial period, Japanese language appeared in every corner of Taiwan. Only after 1945 did Taiwanese Hokkien begin to be revived. However, by this time, Taiwanese Hokkien was subjected to influence from other languages, causing its text reading system to decline. Taiwanese Hokkien began to degenerate only to a common daily living language.[10] Following that, most Taiwanese were unable to read out Chinese poetry or Classical Chinese in Taiwanese.

After the government of the Republic of China gained control of Taiwan, there was a brief cultural exchange with mainland China. However, the Chinese Civil War began another political separation when the Kuomingtang government retreated to Taiwan following their defeat by the communists. This caused the population of Taiwan to increase from 6 million to 8 million. The government subsequently promoted Mandarin and banned the public use of Taiwanese dialect as part of a deliberate political repression, especially in schools and broadcast media. This had substantial impact on the Taiwanese language, causing it to decline. Only after the lifting of martial law in 1987 and the mother tongue movement in the 1990s did Taiwan see a true revival in the Taiwanese language. Today, there are a large number of Taiwanese scholars dedicated to researching the language.

The history of Taiwanese and the interaction with Mandarin is complex and at times controversial. Even the name is somewhat controversial. Some dislike the name Taiwanese as they feel that it belittles other languages spoken on the island such as Mandarin, Hakka, and the aboriginal languages. Others prefer the name Min-nan or Hokkien as this views Taiwanese as a variant of the language spoken in Fujian province in Mainland China. Others dislike the name Min-nan and Hokkien for precisely the same reason. One can also get into similar controversial debates as to whether Taiwanese is a language or a dialect.

Phonology

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taiwanese pronunciation. |

Phonologically, Min Nan is a tonal language with extensive tone sandhi rules. Syllables consist maximally of an initial consonant, a vowel, a final consonant, and a tone; any or all of the consonants or vowels may be nasal.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Alveolo-palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | ||

| Nasal | [m] m ㄇ |

[n] n ㄋ | [ŋ] ng ㄫ | |||||||

| Plosive | Unaspirated | [p] p ㄅ |

[b] b ㆠ |

[t] t ㄉ | [k] k ㄍ |

[g] g ㆣ |

[ʔ] | |||

| Aspirated | [pʰ] ph ㄆ | [tʰ] th ㄊ | [kʰ] kh ㄎ | |||||||

| Affricate | Unaspirated | [ts] ch,ts ㄗ |

[dz] j ㆡ |

[tɕ] chi,tsi ㄐ |

[dʑ] ji ㆢ | |||||

| Aspirated | [tsʰ] chh,tsh ㄘ | [tɕʰ] chhi,tshi ㄑ | ||||||||

| Fricative | [s] s ㄙ | [ɕ] si ㄒ | [h] h ㄏ | |||||||

| Lateral | [l] l ㄌ | |||||||||

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | [m] -m | [n] -n | [ŋ] -ng | |

| Plosive | [p̚] -p ㆴ | [t̚] -t ㆵ | [k̚] -k ㆶ | [ʔ] -h ㆷ |

Unlike many other varieties of Chinese such as Mandarin and Cantonese, there are no native labiodental phonemes.

- Coronal affricates and fricatives become alveolo-palatal before /i/, that is, /dzi/, /tsi/, /tsʰi/, and /si/ are pronounced [dʑi], [tɕi], [tɕʰi], and [ɕi].

- The consonant /dz/ may be realized as a fricative; that is, as [z] in most environments and [ʑ] before /i/.

- The voiced plosives (/b/ and /ɡ/) become the corresponding fricatives ([β] and [ɣ]) in some phonetic contexts.

- H represents a glottal stop /ʔ/ at the end of a syllable.

Vowels

Taiwanese has the following vowels:

| Front | Central | Back | Syllabic consonant | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | Nasal | Simple | Simple | Nasal | ||||

| Close | [i] i ㄧ | [ĩ] iⁿ, inn ㆪ | [u] u ㄨ | [ũ] uⁿ, unn ㆫ |

[m̩] m ㆬ |

[ŋ̍] ng ㆭ | ||

| Mid | [e] e ㆤ | [ẽ] eⁿ, enn ㆥ |

[ɤ], [o] o ㄜㄛ |

[ɔ] o͘, oo ㆦ | [ɔ̃] oⁿ, onn ㆧ | |||

| Open | [a] a ㄚ | [ã] aⁿ, ann ㆩ | ||||||

The vowel ⟨o⟩ is akin to a schwa; in contrast, ⟨o͘⟩ is more open. In addition, there are several diphthongs and triphthongs (for example, ⟨iau⟩). The consonants ⟨m⟩ and ⟨ng⟩ can function as a syllabic nucleus and are therefore included here as vowels. The vowels may be either plain or nasal: ⟨a⟩ is non-nasal, and ⟨aⁿ⟩ is the same vowel with concurrent nasal articulation. This is similar to French, Portuguese, and many other languages.

There are two pronunciations of vowel ⟨o⟩. It is [ɤ] in Southern Taiwan mainly such as Tainan and Kaohsiung, and [o] in Northern Taiwan such as Taipei. But because of people moving and the development of communication, these two pronunciations are common and acceptable throughout the entire island.

Tones

In the traditional analysis, there are eight “tones”, numbered from 1 to 8. Strictly speaking, there are only five tonal contours. But as in other Chinese dialects, the two kinds of stopped syllables are considered also to be “tones” and assigned numbers 4 and 8. In Taiwanese tones 2 and 6 are the same, and thus duplicated in the count. Here the eight tones are shown, following the traditional tone class categorization, named after the tones of Middle Chinese:

Taiwanese tones[11] Tone

numberName POJ

accentPitch in

TaipeiDescription Pitch in

TainanDescription 1 yin level (陰平) a ˥ (55) high ˦ (44) high 2 (6) rising (上聲) á ˥˩ (51) falling ˥˧ (53) high falling 3 yin departing (陰去) à ˧˩ to ˨˩ (31~21) low falling ˩ (11) low 4 yin entering (陰入) ah ˧˨ʔ (32) mid stopped ˨˩ʔ (21) low stopped 5 yang level (陽平) â ˩˦ to ˨˦ (14~24) rising ˨˦ (25) rising 7 yang departing (陽去) ā ˧ (33) mid ˨ (22) mid 8 yang entering (陽入) a̍h ˦ʔ (4) high stopped ˥ʔ (5) high stopped

|

Eight tones of Taiwanese

Demonstration of the tones of Taiwanese: 衫 saⁿ, 短 té, 褲, khò͘, 闊 khoah, 人 lâng, 矮 é, 鼻 phīⁿ, 直 ti̍t. Tone sandhi rules do not apply in this sentence.

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

See (for one example) Wi-vun Taiffalo Chiung's modern phonological analysis in the References, which challenges these notions.

For tones 4 and 8, a final consonant ⟨p⟩, ⟨t⟩, or ⟨k⟩ may appear. When this happens, it is impossible for the syllable to be nasal. Indeed, these are the counterpart to the nasal final consonants ⟨m⟩, ⟨n⟩, and ⟨ng⟩, respectively, in other tones. However, it is possible to have a nasal 4th or 8th tone syllable such as ⟨siaⁿh⟩, as long as there is no final consonant other than ⟨h⟩.

In the dialect spoken near the northern coast of Taiwan, there is no distinction between tones number 8 and number 4 – both are pronounced as if they follow the tone sandhi rules of tone number 4.

Tone number 0, typically written with a double hyphen ⟨--⟩ before the syllable with this tone, is used to mark enclitics denoting the extent of a verb action, the end of a noun phrase, etc. A frequent use of this tone is to denote a question, such as in “Chia̍h-pá--bē?”, literally meaning ‘Have you eaten yet?’. This is realized by speaking the syllable with either a low-falling tone (3) or a low stop (4). The syllable prior to the ⟨--⟩ maintains its original tone.

Syllabic structure

A syllable requires a vowel (or diphthong or triphthong) to appear in the middle. All consonants can appear at the initial position. The consonants ⟨p, t, k⟩ and ⟨m, n, ng⟩ (and some consider ⟨h⟩) may appear at the end of a syllable. Therefore, it is possible to have syllables such as ⟨ngiau⟩ (“(to) tickle”) and ⟨thng⟩ (“soup”). Incidentally, both of these example syllables are nasal: the first has a nasal initial consonant; the second a nasal vowel. Compare with hangul.

Tone sandhi

Taiwanese has extremely extensive tone sandhi (tone-changing) rules: in an utterance, only the last syllable pronounced is not affected by the rules. What an ‘utterance’ (or ‘intonational phrase’) is, in the context of this language, is an ongoing topic for linguistic research. For the purpose of this article, an utterance may be considered a word, a phrase, or a short sentence. The following rules, listed in the traditional pedagogical mnemonic order, govern the pronunciation of tone on each of the syllables affected (that is, all but the last in an utterance):

- If the original tone number is 5, pronounce it as tone number 3 (Quanzhou/Taipei speech) or 7 (Zhangzhou/Tainan speech).

- If the original tone number is 7, pronounce it as tone number 3.

- If the original tone number is 3, pronounce it as tone number 2.

- If the original tone number is 2, pronounce it as tone number 1.

- If the original tone number is 1, pronounce it as tone number 7.

- If the original tone number is 8 and the final consonant is not h (that is, it is p, t, or k), pronounce it as tone number 4.

- If the original tone number is 4 and the final consonant is not h (that is, it is p, t, or k), pronounce it as tone number 8.

- If the original tone number is 8 and the final consonant is h, pronounce it as tone number 3.

- If the original tone number is 4 and the final consonant is h, pronounce it as tone number 2.

See the work by Tiuⁿ Jū-hông and Wi-vun Taiffalo Chiung in the References, and the work by Robert L. Cheng (Tēⁿ Liông-úi) of the University of Hawaii, for modern linguistic approaches to tones and tone sandhi in Taiwanese.

Lexicon

Modern linguistic studies (by Robert L. Cheng and Chin-An Li, for example) estimate that most (75% to 90%) Taiwanese words have cognates in other Chinese languages. False friends do exist; for example, cháu means "to run" in Taiwanese, whereas the Mandarin cognate, zǒu, means "to walk". Moreover, cognates may have different lexical categories; for example, the morpheme phīⁿ means not only "nose" (a noun, as in Mandarin bí) but also "to smell" (a verb, unlike Mandarin).

Among the apparently cognate-less words are many basic words with properties that contrast with similar-meaning words of pan-Chinese derivation. Often the former group lacks a standard Han character, and the words are variously considered colloquial, intimate, vulgar, uncultured, or more concrete in meaning than the pan-Chinese synonym. Some examples: lâng (person, concrete) vs. jîn (人, person, abstract); cha-bó͘ (查某, woman) vs. lú-jîn (女人, woman, literary). Unlike the English Germanic/Latin contrast, however, the two groups of Taiwanese words cannot be as strongly attributed to the influences of two disparate linguistic sources.

Extensive contact with the Japanese language has left a legacy of Japanese loanwords (172 are recorded in the Ministry of Education's Taiwanese Minnan Dictionary of Common Words).[12] Although a very small percentage of the vocabulary, their usage tends to be high-frequency because of their relevance to modern society and popular culture. Examples are: o͘-tó͘-bái (from オートバイ ootobai "autobike", an "Engrish" word) and pháng (from パン pan "bread", which is itself a loanword from Portuguese). Grammatical particles borrowed from Japanese, notably te̍k (from teki 的) and ka (from か), show up in the Taiwanese of older speakers.

Whereas Mandarin attaches a syllabic suffix to the singular pronoun to make a collective form, Taiwanese pronouns are collectivized through nasalization. For example, i (he/she/it) and goá (I) become in (they) and goán (we), respectively. The -n thus represents a subsyllabic morpheme. Like all other Chinese languages, Taiwanese does not have true plurals.

Unlike English, Taiwanese has two first-person plural pronouns. This distinction is called inclusive, which includes the addressee, and exclusive, which excludes the addressee. Thus, goán means we excluding you, while lán means we including you (similar to pluralis auctoris). The inclusive lán may be used to express politeness or solidarity, as in the example of a speaker asking a stranger "Where do we live?", but meaning "Where do you live?".

Syntax

|

‘Kin-á-jit hit-ê cha-bó͘ gín-á lâi góan tau khòaⁿ góa.’

An audio sample for a simple sentence, meaning “Today that little girl came to my house to see me”.)

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The syntax of Taiwanese is similar to southern Chinese languages such as Hakka and Cantonese. The sequence ‘subject–verb–object’ is typical as in, for example, Mandarin, but ‘subject–object–verb’ or the passive voice (with the sequence ‘object–subject–verb’) is possible with particles. Take a simple sentence for example: ‘I hold you.’ The words involved are: goá (‘I’ or ‘me’), phō (‘to hold’), lí (‘you’).

- Subject–verb–object (typical sequence): The sentence in the typical sequence would be: Goá phō lí. (‘I hold you.’)

- Subject–kā–object–verb: Another sentence of roughly equivalent meaning is Goá kā lí phō, with the slight connotation of ‘I take you and hold’ or ‘I get to you and hold’.

- Object hō͘ subject–verb (the passive voice): Then, Lí hō͘ goá phō means the same thing but in the passive voice, with the connotation of ‘You allow yourself to be held by me’ or ‘You make yourself available for my holding’.

With this, more complicated sentences can be constructed: Goá kā chúi hō͘ lí lim (‘I give water for you to drink’: chúi means ‘water’; lim is ‘to drink’).

This article can only give a few very simple examples on the syntax, for flavour. Linguistic work on the syntax of Taiwanese is still a (quite nascent) scholarly topic being explored.

Scripts and orthographies

Taiwanese does not have a strong written tradition. Until the late 19th century, Taiwanese speakers wrote solely in Classical Chinese. Among many system of writing Taiwanese using Latin characters, the most used is called pe̍h-oē-jī (POJ) was developed in the 19th century, while the Taiwanese Romanization System has been officially promoted since 2006 by Taiwan's Ministry of Education. (For additional romanized systems, see references in "Orthography in Latin characters", below.) Nonetheless, Taiwanese speakers nowadays most commonly write in Standard Chinese (Mandarin), though many of the same characters are also used to write Taiwanese.

Han characters

In most cases, Taiwanese speakers write using the script called Han characters as in Mandarin, although there are a number of special characters which are unique to Taiwanese and which are sometimes used in informal writing. Where Han characters are used, they are not always etymological or genetic; the borrowing of similar-sounding or similar-meaning characters is a common practice. Mandarin-Taiwanese bilingual speakers sometimes attempt to represent the sounds by adopting similar-sounding Mandarin Han characters. For example, the Han characters of the vulgar slang ‘khoàⁿ siáⁿ siâu’ (看三小, substituted for the etymologically correct 看啥痟, meaning ‘What the hell are you looking at?’) has very little meaning in Mandarin and may not be readily understood by a Taiwanese monolingual, as knowledge of Mandarin character readings is required to fully decipher it.

In 2007, the Ministry of Education in Taiwan published a list of 300 Han characters standardized for the use of writing Taiwanese and implemented the teaching of them in schools.[13] In 2008, the ministry published a second list of 100 characters, and in 2009 added 300 more, giving a total of 700 standardized characters used to write uniquely Taiwanese Hokkien words. With increasing literacy in Taiwanese, there are currently more Taiwanese online bloggers who write Taiwanese Hokkien online using these standardized Chinese characters. Han characters are also used by Taiwan’s Hokkien literary circle for Hokkien poets and writers to write literature or poetry in Taiwanese Hokkien.

Orthography in Latin characters

There are several Latin-based orthographies, the oldest being Pe̍h-oē-jī (POJ, meaning “vernacular writing”), developed in the 19th century. Taiwanese Romanization System (Tâi-ôan Lô-má-jī, Tâi-Lô) and Taiwanese Language Phonetic Alphabet (TLPA) are two later adaptations of POJ. Other 20th-century innovations include Daighi tongiong pingim (DT), Ganvsig daiuuan bhanlam ghiw tongiong pingimv (GDT), Modern Literal Taiwanese (MLT), Simplified MLT (SMLT), Phofsit Daibuun (PSDB). The last four employ tonal spelling to indicate tone without use of diacritic symbols, but alphabets instead.

In POJ, the traditional list of letters is

- a b ch chh e g h i j k kh l m n ng o o͘ p ph s t th (ts) u

Twenty-four in all, including the obsolete ⟨ts⟩, which was used to represent the modern ⟨ch⟩ at some places. The additional necessities are the nasal symbol ⟨ⁿ⟩ (superscript ⟨n⟩; the uppercase form ⟨N⟩ is sometimes used in all caps texts,[14] such as book titles or section headings), and the tonal diacritics. POJ was developed first by Presbyterian missionaries and later by the indigenous Presbyterian Church in Taiwan; they have been active in promoting the language since the late 19th century. Recently there has been an increase in texts using a mixed orthography of Han characters and romanization, although these texts remain uncommon.

In 2006, the National Languages Committee (Ministry of Education, Republic of China) proposed an alphabet called ‘Tâi-ôan Lô-má-jī’ (‘Tâi-lô’, literally ‘romanized orthography for Taiwanese’). This alphabet reconciles two of the more senior orthographies, TLPA and POJ.[15] The changes for the consonants involved using ⟨ts⟩ for POJ's ⟨ch⟩ (reverting to the orthography in the 19th century), and ⟨tsh⟩ for ⟨chh⟩. For the vowels, ⟨o͘⟩ could optionally represented as ⟨oo⟩. The nasal mark ⟨ⁿ⟩ could also be represented optionally as ⟨nn⟩. The rest of the alphabet, most notably the use of diacritics to mark the tones, appeared to keep to the POJ tradition. One of the aims of this compromise was to curb any increase of ‘market share’ for Daighi tongiong pingim/Tongyong Pinyin.[16] It is unclear whether the community will adopt this new agreement.

Orthographies in kana and in bopomofo

There was an orthography of Taiwanese based on the Japanese kana during Japanese rule. The Kuomintang government also tried to introduce an orthography in bopomofo.

Comparison of orthographies

Here the different orthographies are compared:

| IPA | a | ap | at | ak | aʔ | ã | ɔ | ɔk | ɔ̃ | ə | o | e | ẽ | i | ɪɛn | iŋ |

| Pe̍h-ōe-jī | a | ap | at | ak | ah | aⁿ | o͘ | ok | oⁿ | o | o | e | eⁿ | i | ian | eng |

| Revised TLPA | a | ap | at | ak | ah | aN | oo | ok | ooN | o | o | e | eN | i | ian | ing |

| TLPA | a | ap | at | ak | ah | ann | oo | ok | oonn | o | o | e | enn | i | ian | ing |

| BP | a | ap | at | ak | ah | na | oo | ok | noo | o | o | e | ne | i | ian | ing |

| MLT | a | ab/ap | ad/at | ag/ak | aq/ah | va | o | og/ok | vo | ø | ø | e | ve | i | ien | eng |

| DT | a | āp/ap | āt/at | āk/ak | āh/ah | ann/aⁿ | o | ok | onn/oⁿ | or | or | e | enn/eⁿ | i | ian/en | ing |

| Taiwanese kana | アア | アプ | アツ | アク | アア | アア | オオ | オク | オオ | オオ | ヲヲ | エエ | エエ | イイ | イエヌ | イエン |

| Extended bopomofo | ㄚ | ㄚㆴ | ㄚㆵ | ㄚㆶ | ㄚㆷ | ㆩ | ㆦ | ㆦㆶ | ㆧ | ㄜ | ㄛ | ㆤ | ㆥ | ㄧ | ㄧㄢ | ㄧㄥ |

| Tâi-lô | a | ap | at | ak | ah | ann | oo͘ | ok | onn | o | o | e | enn | i | ian | ing |

| Example (traditional Chinese) | 亞 洲 |

壓 力 |

警 察 |

沃 水 |

牛 肉 |

三 十 |

烏 色 |

中 國 |

澳 洲 |

澳 洲 |

下 晡 |

醫 學 |

鉛 筆 |

英 國 | ||

| Example (simplified Chinese) | 亚 洲 |

压 力 |

警 察 |

沃 水 |

牛 肉 |

三 十 |

烏 色 |

中 国 |

澳 洲 |

澳 洲 |

下 晡 |

医 学 |

铅 笔 |

英 国 |

| IPA | ɪk | ĩ | ai | aĩ | au | am | ɔm | m̩ | ɔŋ | ŋ̍ | u | ua | ue | uai | uan | ɨ | (i)ũ |

| Pe̍h-ōe-jī | ek | iⁿ | ai | aiⁿ | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | oa | oe | oai | oan | i | (i)uⁿ |

| Revised TLPA | ik | iN | ai | aiN | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | ua | ue | uai | uan | ir | (i)uN |

| TLPA | ik | inn | ai | ainn | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | ua | ue | uai | uan | ir | (i)unn |

| BP | ik | ni | ai | nai | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | ua | ue | uai | uan | i | n(i)u |

| MLT | eg/ek | vi | ai | vai | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | oa | oe | oai | oan | i | v(i)u |

| DT | ik | inn/iⁿ | ai | ainn/aiⁿ | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | ua | ue | uai | uan | i | (i)unn/uⁿ |

| Taiwanese kana | イエク | イイ | アイ | アイ | アウ | アム | オム | ム | オン | ン | ウウ | ヲア | ヲエ | ヲアイ | ヲアヌ | ウウ | ウウ |

| Extended bopomofo | ㄧㆶ | ㆪ | ㄞ | ㆮ | ㆯ | ㆰ | ㆱ | ㆬ | ㆲ | ㆭ | ㄨ | ㄨㄚ | ㄨㆤ | ㄨㄞ | ㄨㄢ | ㆨ | ㆫ |

| Tâi-lô | ik | inn | ai | ainn | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | ua | ue | uai | uan | i | iunn |

| Example (traditional Chinese) | 翻 譯 |

病 院 |

愛 情 |

歐 洲 |

暗 時 |

阿 姆 |

王 梨 |

黃 色 |

有 無 |

歌 曲 |

講 話 |

奇 怪 |

人 員 |

豬 肉 |

舀 水 | ||

| Example (simplified Chinese) | 翻 译 |

病 院 |

爱 情 |

欧 洲 |

暗 时 |

阿 姆 |

王 梨 |

黄 色 |

有 无 |

歌 曲 |

讲 话 |

奇 怪 |

人 员 |

猪 肉 |

舀 水 |

| IPA | p | b | pʰ | m | t | tʰ | n | nŋ | l | k | ɡ | kʰ | h | tɕi | ʑi | tɕʰi | ɕi | ts | dz | tsʰ | s |

| Pe̍h-ōe-jī | p | b | ph | m | t | th | n | nng | l | k | g | kh | h | chi | ji | chhi | si | ch | j | chh | s |

| Revised TLPA | p | b | ph | m | t | th | n | nng | l | k | g | kh | h | zi | ji | ci | si | z | j | c | s |

| TLPA | p | b | ph | m | t | th | n | nng | l | k | g | kh | h | zi | ji | ci | si | z | j | c | s |

| BP | b | bb | p | bb | d | t | n | lng | l | g | gg | k | h | zi | li | ci | si | z | l | c | s |

| MLT | p | b | ph | m | t | th | n | nng | l | k | g | kh | h | ci | ji | chi | si | z | j | zh | s |

| DT | b | bh | p | m | d | t | n | nng | l | g | gh | k | h | zi | r | ci | si | z | r | c | s |

| Taiwanese kana | パア | バア | パ̣ア | マア | タア | タ̣ア | ナア | ヌン | ラア | カア | ガア | カ̣ア | ハア | チイ | ジイ | チ̣イ | シイ | サア | ザア | サ̣ア | サア |

| Extended bopomofo | ㄅ | ㆠ | ㄆ | ㄇ | ㄉ | ㄊ | ㄋ | ㄋㆭ | ㄌ | ㄍ | ㆣ | ㄎ | ㄏ | ㄐ | ㆢ | ㄑ | ㄒ | ㄗ | ㆡ | ㄘ | ㄙ |

| Tâi-lô | p | b | ph | m | t | th | n | nng | l | k | g | kh | h | tsi | ji | tshi | si | ts | j | tsh | s |

| Example (traditional Chinese) | 報 紙 |

閩 南 |

普 通 |

請 問 |

豬 肉 |

普 通 |

過 年 |

雞 卵 |

樂 觀 |

價 值 |

牛 奶 |

客 廳 |

煩 惱 |

支 持 |

漢 字 |

支 持 |

是 否 |

報 紙 |

熱 天 |

參 加 |

司 法 |

| Example (simplified Chinese) | 报 纸 |

闽 南 |

普 通 |

请 问 |

猪 肉 |

普 通 |

过 年 |

鸡 卵 |

乐 观 |

价 值 |

牛 奶 |

客 厅 |

烦 恼 |

支 持 |

汉 字 |

支 持 |

是 否 |

报 纸 |

热 天 |

参 加 |

司 法 |

| Tone name | Yin level 陰平(1) | Yin rising 陰上(2) | Yin departing 陰去(3) | Yin entering 陰入(4) | Yang level 陽平(5) | Yang rising 陽上(6) | Yang departing 陽去(7) | Yang entering 陽入(8) | High rising (9) | Neutral tone (0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | a˥ | a˥˧ | a˨˩ | ap˩ at˩ ak˩ aʔ˩ | a˧˥ | a˥˧ | a˧ | ap˥ at˥ ak˥ aʔ˥ | a˥˥ | a˨ |

| Pe̍h-ōe-jī | a | á | à | ap at ak ah | â | á | ā | a̍p a̍t a̍k a̍h | --a | |

| Revised TLPA TLPA | a1 | a2 | a3 | ap4 at4 ak4 ah4 | a5 | a2 (6=2) | a7 | ap8 at8 ak8 ah8 | a9 | a0 |

| BP | ā | ǎ | à | āp āt āk āh | á | ǎ | â | áp át ák áh | ||

| MLT | af | ar | ax | ab ad ag aq | aa | aar | a | ap at ak ah | ~a | |

| DT | a | à | â | āp āt āk āh | ǎ | à | ā | ap at ak ah | á | å |

| Taiwanese kana (normal vowels) | アア | アア | アア | アプ アツ アク アア | アア | アア | アア | アプ アツ アク アア | ||

| Taiwanese kana (nasal vowels) | アア | アア | アア | アプ アツ アク アア | アア | アア | アア | アプ アツ アク アア | ||

| Zhuyin | ㄚ | ㄚˋ | ㄚᒻ | ㄚㆴ ㄚㆵ ㄚㆶ ㄚㆷ | ㄚˊ | ㄚˋ | ㄚ⊦ | ㄚㆴ̇ ㄚㆵ̇ ㄚㆶ̇ ㄚㆷ̇ | ||

| Tâi-lô | a | á | à | ah | â | á | ā | a̍h | ||

| Example (traditional Chinese) |

公司 | 報紙 | 興趣 | 血壓 警察 中國 牛肉 |

人員 | 草地 | 配合 法律 文學 歇熱 |

社子 | 進去 | |

| Example (simplified Chinese) |

公司 | 报纸 | 兴趣 | 血压 警察 中国 牛肉 |

人员 | 草地 | 配合 法律 文学 歇热 |

社子 | 進去 |

- Note: The bopomofo extended characters in the zhuyin row require a UTF-8 font capable of displaying Unicode values 31A0–31B7 (ex. Code2000 true type font).

Computing

Many keyboard layouts and input methods for entering either Latin or Han characters in Taiwanese are available. Some of them are free-of-charge, some commercial.

The language Min-nan is registered per RFC 3066 as zh-min-nan.[17] Taiwanese can be represented as ‘zh-min-nan-TW’.

When writing Taiwanese in Han characters, some writers create ‘new’ characters when they consider it is impossible to use directly or borrow existing ones; this corresponds to similar practices in character usage in Cantonese, Vietnamese chữ nôm, Korean hanja and Japanese kanji. These are usually not encoded in Unicode (or the corresponding ISO/IEC 10646: Universal Character Set), thus creating problems in computer processing.

All Latin characters required by pe̍h-oē-jī can be represented using Unicode (or the corresponding ISO/IEC 10646: Universal character set), using precomposed or combining (diacritics) characters.

Prior to June 2004, the vowel [ɔ] akin to but more open than o, written with a ‘dot above right’, was not encoded. The usual workaround was to use the (stand-alone; spacing) character ‘middle dot’ (U+00B7, ·) or less commonly the combining character ‘dot above’ (U+0307). As these are far from ideal, since 1997 proposals have been submitted to the ISO/IEC working group in charge of ISO/IEC 10646 – namely, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 – to encode a new combining character ‘dot above right’. This is now officially assigned to U+0358 (see documents N1593, N2507, N2628, N2699, and N2770). Font support has followed: for example, in Charis SIL.

Sociolinguistics

Regional variations

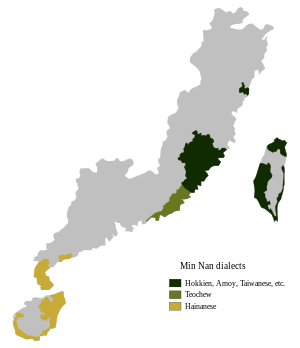

Within the wider Hokkien speaking community in Southeast Asia, Ē-mn̂g (Amoy or Xiamen) is historically the variant of prestige, with other major variants from Choâⁿ-chiu/Choân-chiu (Chinchew or Quanzhou in Fujian) and Chiang-chiu (Changchew or Zhangzhou in Fujian). Another Min Nan language, Tiô-chiu (Teochew or Chaozhou in eastern Guangdong) is also widely spoken in these regions.

In Taiwan, however, the Tâi-lâm (Tainan, southern Taiwan) speech is the prestige variant, and the other major variants are the northern speech, the central speech (near Taichung and the port town of Lugang in Changhua County), and the northern (northeastern) coastal speech (dominant in Yilan). The distinguishing feature of the coastal speech is the use of the vowel ⟨uiⁿ⟩ in place of ⟨ng⟩. The northern speech is distinguished by the absence of the 8th tone, and some vowel exchanges (for example, ⟨i⟩ and ⟨u⟩, ⟨e⟩ and ⟨oe⟩). The central speech has an additional vowel [ɨ] or [ø] between ⟨i⟩ and ⟨u⟩, which may be represented as ⟨ö⟩. There are also a number of other pronunciation and lexical differences between the Taiwanese variants.[18][19]

Some scholars have divided Taiwanese into 5 subgroups, based on geographic region:[20]

- Haikou accent (海口腔, Hái-kháu-khiuⁿ): seaport, based on the Quanzhou dialect (represented by the Lugang accent)

- Pianhai accent (偏海腔, Phian-hái-khiuⁿ): coastal (represented by the Nianliao accent)

- Neipu accent (內鋪腔, Lāi-po͘-khiuⁿ): inner plain, based on the Zhangzhou dialect (represented by the Yilan accent)

- Piannei accent (偏內腔, Phian-lāi-khiuⁿ): interior (represented by the Taibao accent)

- Tongxing accent (通行腔, Thong-hêng-khiuⁿ): common accents (represented by the Taipei accent in the north and the Tainan accent in the south)

Quanzhou–Zhangzhou inclinations

Hokkien immigrants to Taiwan originated from Quanzhou prefecture (44.8%) and Zhangzhou prefecture (35.2%). The original phonology from these regions was spread around Taiwan during the immigration process. With the advanced development of transportation and greater mobility of the Taiwanese population, Taiwanese Hokkien speech has steered itself towards a mixture of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou speech, known as Chiang–Chôaⁿ-lām (漳泉濫, in Mandarin Zhāng–Quán làn).[21] Due to different proportion of mixture, some regions are inclined more towards Quanzhou accent, while others are inclined more towards Zhangzhou accent.

In general, Zhangzhou accent is more common within the mountainous region of Taiwan and is known as the Neipu accent (內埔腔); Quanzhou accent is more common along the coastal region and is known as the Haikou accent (海口腔). The regional variation within Taiwanese Hokkien is simply a variation in the proportion of mixture of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou accent. It ranges from Lugang accent (based on Quanzhou accent) on one end, to the northern coastal Yilan accent (based on Zhangzhou accent) on another end. Tainan, Kaohsiung and Taitung accents, on the other hand, are closest to Taiwanese prestige accent.

| Quanzhou accent |

|---|

| Lugang |

| Penghu, Taixi, Dajia coastal region (Haikou accent) |

| Taipei, Hsinchu (very similar to Amoy accent) |

| Tainan, Kaohsiung and Taitung (prestige accent) |

| Taichung, Changhua and Chiayi (Neibu accent) |

| Yilan |

| Zhangzhou accent |

Fluency

A great majority of people in Taiwan can speak both Mandarin Chinese and Taiwanese although the degree of fluency varies widely. There are however small but significant numbers of people in Taiwan, mainly but not exclusively Hakka and Mainlanders, who cannot speak Taiwanese fluently. A shrinking percentage of the population, mainly people born before the 1950s, cannot speak Mandarin at all, or learned to speak Mandarin later in life, though some of these speak Japanese fluently. Urban, working-class Hakkas as well as younger, southern-Taiwan Mainlanders tend to have better, even native-like fluency. Approximately half of the Hakka in Taiwan do speak Taiwanese. There are many families of mixed Hakka, Hoklo, and Aboriginal bloodlines. There is, however, a large percentage of people in Taiwan, regardless of their background, whose ability to understand and read written Taiwanese is greater than their ability to speak it. This is the case with some singers who can sing Taiwanese songs with native-like authenticity, but can not/neither speak or/nor understand the language.

Which variant is used depends strongly on the context, and in general people will use Mandarin in more formal situations and Taiwanese in more informal situations. Taiwanese tends to get used more in rural areas, while Mandarin is used more in urban settings. Older people tend to use Taiwanese, while younger people tend to use Mandarin. In the broadcast media where Mandarin is used in many genres, soap opera and variety shows can also be found in Taiwanese. Political news is broadcast in both Taiwanese and Mandarin.

Sociolinguistics and gender

Taiwanese is also perceived by some to have a slight masculine leaning, making it more popular among the males of the younger population. It is sometimes perceived as "unladylike" when spoken by the females of the younger population.

Special literary and art forms

Chhit-jī-á (literally, "that which has seven syllables") is a poetic meter where each verse has 7 syllables.

There is a special form of musical/dramatic performance koa-á-hì: the Taiwanese opera; the subject matter is usually a historical event. A similar form pò͘-tē-hì (glove puppetry) is also unique and has been elaborated in the past two decades into impressive televised spectacles.

See Taiwanese cuisine for names of several local dishes.

Bible translations

As with many other languages, the translations of the Bible in Taiwanese marked milestones in the standardization attempts of the language and its orthography.

The first translation of the Bible in Amoy or Taiwanese in the pe̍h-ōe-jī orthography was by the first missionary to Taiwan, James Laidlaw Maxwell, with the New Testament Lán ê Kiù-chú Iâ-so͘ Ki-tok ê Sin-iok published in 1873 and the Old Testament Kū-iok ê Sèng Keng in 1884.

The next translation of the Bible in Taiwanese or Amoy was by the missionary to Taiwan, Thomas Barclay, carried out in Fujian and Taiwan.[22][23] A New Testament translation was completed and published in 1916. The resulting work containing the Old and the New Testaments, in the pe̍h-ōe-jī orthography, was completed in 1930 and published in 1933 as the Sin-kū-iok ê Sèng-keng (Amoy Romanized Bible). This edition was later transliterated into Han characters and published as Sèng-keng Tâi-gí Hàn-jī Pún (聖經台語漢字本) in 1996.[24]

The Ko-Tân (Kerygma) Colloquial Taiwanese Version of the New Testament (Sin-iok) in pe̍h-ōe-jī, also known as the Red-Cover Bible (Âng-phoê Sèng-keng), was published in 1973 as an ecumenical effort between the Protestant Presbyterian Church in Taiwan and the Roman Catholic mission Maryknoll. This translation used a more modern vocabulary (somewhat influenced by Mandarin), and reflected the central Taiwan dialect, as the Maryknoll mission was based near Tâi-tiong. It was soon confiscated by the Kuomintang government (which objected to the use of Latin orthography) in 1975.

A translation using the principle of functional equivalence, Hiān-tāi Tâi-gú Sin-iok Sèng-keng (Today's Taiwanese Romanized Version), containing only the New Testament, again in pe̍h-ōe-jī, was published in 2008[25] as a collaboration between the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan and the Bible Society in Taiwan. A translation of the Old Testament, following the same principle, is being prepared.[26]

Politics

Until the 1980s, the use of Taiwanese, along with all dialects other than Mandarin, was discouraged by the Kuomintang through measures such as banning its use in schools and limiting the amount of Taiwanese broadcast on electronic media. These measures were removed by the 1990s, and Taiwanese became an emblem of localization. Mandarin remains the predominant language of education, although there is a "mother tongue" language requirement in Taiwanese schools which can be satisfied with student's choice of mother-tongue: Taiwanese, Hakka, or aboriginal languages.

Although the use of Taiwanese over Mandarin was historically part of the Taiwan independence movement, the linkage between politics and language is not as strong as it once was. Some fluency in Taiwanese is desirable for political office in Taiwan for both independence and unificationist politicians. At the same time even some supporters of Taiwan independence have played down its connection with Taiwanese language in order to gain the support of the Mainlanders and Hakka.

James Soong restricted the use of Taiwanese and other local tongues in broadcasting while serving as Director of the Government Information Office earlier in his career, but later became one of the first Mainlander politicians to use Taiwanese in semi-formal occasions. Since then, politicians opposed to Taiwan independence have used it frequently in rallies even when they are not native speakers of the language and speak it badly. Conversely, politicians who have traditionally been identified with Taiwan independence have used Mandarin on formal occasions and semi-formal occasions such as press conferences. An example of the latter is former President Chen Shui-bian who uses Mandarin in all official state speeches, but uses mainly Taiwanese in political rallies and some informal state occasions such as New Year greetings. The current DPP chairwoman Tsai Ing-wen have been criticised by her supporters for not using Taiwanese in speeches.[27] President Ma Ying-jeou spoke in Taiwanese during his 2008 Double Ten Day speech when he was talking about the state of the economy in Taiwan.

In the early 21st century, there are few differences in language usage between the anti-independence leaning Pan-Blue Coalition and the independence leaning Pan-Green Coalition. Both tend to use Taiwanese at political rallies and sometimes in informal interviews and both tend to use Mandarin at formal press conferences and official state functions. Both also tend to use more Mandarin in northern Taiwan and more Taiwanese in southern Taiwan. However at official party gatherings (as opposed to both Mandarin-leaning state functions and Taiwanese-leaning party rallies), the DPP tends to use Taiwanese while KMT and PFP tend to use Mandarin. The Taiwan Solidarity Union, which advocates a strong line on Taiwan independence, tends to use Taiwanese even in formal press conferences. In speaking, politicians will frequently code switch. In writing, almost everyone uses vernacular Mandarin which is further from Taiwanese, and the use of semi-alphabetic writing or even colloquial Taiwanese characters is rare.

Despite these commonalities, there are still different attitudes toward the relationship between Taiwanese and Mandarin. In general, while supporters of Chinese reunification believe that all languages used on Taiwan should be respected, they tend to believe that Mandarin should have a preferred status as the common working language between different groups. Supporters of Taiwan independence tend to believe that either Taiwanese should be preferred or that no language should be preferred.

In 2002, the Taiwan Solidarity Union, a party with about 10% of the Legislative Yuan seats at the time, suggested making Taiwanese a second official language. This proposal encountered strong opposition not only from Mainlander groups but also from Hakka and aboriginal groups who felt that it would slight their home languages, as well as others including Hoklo who objected to the proposal on logistical grounds and on the grounds that it would increase ethnic tensions. Because of these objections, support for this measure is lukewarm among moderate Taiwan independence supporters, and the proposal did not pass.

In 2003, there was a controversy when parts of the civil service examination for judges were written in characters used only in Taiwanese. After strong objections, these questions were not used in scoring. As with the official-language controversy, objections to the use of Taiwanese came not only from Mainlander groups, but also Hoklo, Hakka and aborigines.

Mother tongue movement

Taiwanization developed in the 1990s into a ‘mother tongue movement’ aiming to save, preserve, and develop the local ethnic culture and language of Holo (Taiwanese Hokkien), Hakka, and aborigines. The effort to save declining languages has since allowed them to flourish. In 1993, Taiwan became the first country in the world to implement the teaching of Taiwanese Hokkien in schools. By 2001, Taiwanese languages such as Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka, and aboriginal languages were taught in all Taiwanese schools.[28] Taiwan also has its own literary circle whereby Hokkien poets and writers compose poetry and literature in Taiwanese Hokkien on a regular basis. This mother tongue movement is ongoing.

As a result of the mother tongue movement, Taiwan has emerged as a significant cultural hub for Hokkien in the world in the 21st century. It also plans to be the major export center for Hokkien culture worldwide in the 21st century.[29]

Scholarship

Donald B. Snow, author of Cantonese as Written Language: The Growth of a Written Chinese Vernacular, described Written Taiwanese, published in 2004 and written by Henning Klöter, as "the most comprehensive English-language study of written Taiwanese" as of 2004.[30]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Taiwanese Hokkien reference at Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013)

- ↑ 大眾運輸工具播音語言平等保障法

- ↑ Ethnologue

- ↑ Mei, Tsu-lin (1970). Tones and Prosody in Middle Chinese and The Origin of The Rising Tone 30. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. pp. 86–110.

- ↑ 教育部,歷史文化學習網,《重要貿易港口-泉州》

- ↑ 臺灣省資料館,史蹟文物簡介,《歷代之經營--明代》

- ↑ 洪惟仁,《臺灣河佬語聲調研究》,1987年。

- ↑ 泉州旅游信息网,泉州方言文化

- ↑ 《台語文運動訪談暨史料彙編》,楊允言、張學謙、呂美親,國史館,2008-03-01

- ↑ 洪惟仁,《臺灣方言之旅》,前衛出版社,1991年:145頁。ISBN 957-9512-31-0。

- ↑ 國臺對照活用辭典 (Mandarin-Taiwanese Comparative Living Dictionary), page 2691 (in Mandarin, Min Nan). ISBN 957-32-4088-2.

- ↑ "外來詞". 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 (in Chinese). Ministry of Education, R.O.C. 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ↑ 教育部公布閩南語300字推薦用字 卡拉OK用字也被選用 (Ministry of Education in Taiwan announces 300 recommended Hokkien words, Karaoke words are also selected); 「臺灣閩南語推薦用字(第1批)」已公布於網站,歡迎各界使用 (Announcement of recommended words for Taiwanese Hokkien)

- ↑ Tè Khái-sū (1999) Writing Latinized Taiwanese Languages with Unicode

- ↑ 臺灣閩南語羅馬字拼音方案 (Orthographic system for the Minnan language in Taiwan, ‘Tâi-ôan Lô-má-jī’)

- ↑ 教育部國語推行委員會: 關於閩南語拼音整合工作相關問題說帖 (National Languages Committee: On the integration of Minnan orthographies), 2006-10-16

- ↑ RFC 3066 Language code assignments

- ↑ "方言差»詞彙差異表". 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 (in Chinese). Ministry of Education, R.O.C. 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ↑ "方言差»語音差異表". 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 (in Chinese). Ministry of Education, R.O.C. 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ↑ Klöter, Henning (2005). Written Taiwanese 2. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 2–5. ISBN 978-3-447-05093-7.

- ↑ Ang Ui-jin, 1987

- ↑ "本土聖經" (in traditional Chinese). Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "書評『聖經--台語漢字本』" (in Japanese). Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ 台語信望愛: 《當上帝開嘴講台語》: 4.1.4 《台語漢字本》

- ↑ PeoPo: 現代台語新約羅馬字聖經 出版感謝e話

- ↑ 台灣聖經公會 (The Bible Society of Taiwan): 台語聖經

- ↑ 蔡英文不說台語 高雄人涼了半截 (Tsai Ing-wen doesn't speak Taiwanese; The people in Kaohsiung feel half-disappointed) (Traditional Chinese), retrieved on 12 October 2008

- ↑ 台灣鄉土教育發展史 (The education history of local Taiwanese languages)

- ↑ National Policy Foundation: 馬蕭文化政策 (Cultural policies of the Ma Administration)

- ↑ Snow, p. 261.

Books cited

- Snow, Donald B. Cantonese as Written Language: The Growth of a Written Chinese Vernacular. Hong Kong University Press, 2004. ISBN 962209709X, 9789622097094.

Further reading

Books and other material

(As English language material on Taiwanese learning is limited, Japanese and German books are also listed here.)

- English textbooks & dictionaries

- Yeh, Chieh-Ting; Lee, Marian (2005), Harvard Taiwanese 101, Tainan: King-an Publishing, ISBN 957-29355-9-3 Format: Paperback and CDs

- Su-chu Wu, Bodman, Nicholas C.: Spoken Taiwanese with cassette(s), 1980/2001, ISBN 0-87950-461-7 or ISBN 0-87950-460-9 or ISBN 0-87950-462-5

- Campbell, William: Ē-mn̂g-im Sin Jī-tián (Dictionary of the Amoy Vernacular). Tainan, Taiwan: Tâi-oân Kàu-hoē Kong-pò-siā (Taiwan Church Press, Presbyterian Church in Taiwan). June 1993 (First published July 1913).

- Iâu Chèng-to: Cheng-soán Pe̍h-oē-jī (Concise Colloquial Writing). Tainan, Taiwan: Jîn-kong (an imprint of the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan). 1992.

- Tân, K. T: A Chinese-English Dictionary: Taiwan Dialect. Taipei: Southern Materials Center. 1978.

- Maryknoll Language Service Center: English-Amoy Dictionary. Taichung, Taiwan: Maryknoll Fathers. 1979.

- Klöter, Henning. Written Taiwanese. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2005. ISBN 3-447-05093-4.

- Japanese publications

- Higuchi, Yasushi (樋口 靖 Higuchi Yasushi): 台湾語会話, 2000, ISBN 4-497-20004-3 (Good and yet concise introduction to the Taiwanese language in Japanese; CD: ISBN 4-497-20006-X)

- Zhao, Yihua (趙 怡華 Zhào Yíhuá): はじめての台湾語, 2003, ISBN 4-7569-0665-6 (Introduction to Taiwanese [and Mandarin]; in Japanese).

- Zheng, Zhenghao (鄭 正浩 Zhèng Zhènghào): 台湾語基本単語2000, 1996, ISBN 4-87615-697-2 (Basic vocabulary in Taiwanese 2000; in Japanese).

- Zhao, Yihua (趙 怡華 Zhào Yíhuá), Chen Fenghui (陳 豐惠 Chén Fēnghuì), Kaori Takao (たかお かおり Takao Kaori), 2006, 絵でわかる台湾語会話. ISBN 978-4-7569-0991-6 (Conversations in Taiwanese [and Mandarin] with illustrations; in Japanese).

- Others

- Katharina Sommer, Xie Shu-Kai: Taiwanisch Wort für Wort, 2004, ISBN 3-89416-348-8 (Taiwanese for travellers, in German. CD: ISBN 3-8317-6094-2)

- Articles and other resources

- Tiuⁿ Jū-hông: Principles of Pe̍h-oē-jī or the Taiwanese Orthography: an introduction to its sound-symbol correspondences and related issues. Taipei: Crane Publishing, 2001. ISBN 957-2053-07-8

- Wi-vun Taiffalo Chiung: Tone Change in Taiwanese: Age and Geographic Factors. (Archive)

- Taiwanese learning resources (a good bibliography in English) (Archive)

External links

| Chinese (Min Nan) edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- On the language

- An introduction to the Taiwanese language for English speakers

- Blog on the Taiwanese language and language education in Taiwan

- How to Forget Your Mother Tongue and Remember Your National Language, by Victor H. Mair.

- Dictionaries

- By the Republic of China's Ministry of Education (Chinese)

- Taiwanese-Mandarin on-line dictionary

- Taiwanese Hokkien Han Character Dictionary

- Taiwanese-Hakka-Mandarin on-line (Chinese)

- The Maryknoll Taiwanese-English Dictionary and English-Amoy Dictionary (PDF format, over 1000 pages)

- Learning aids

- Intermediate Taiwanese grammar (as a blog)

- Taiwanese vocabulary: word of the day (blog)

- Taiwanese teaching material: Nursery rhymes and songs in Han characters and romanization w/ recordings in MP3

- Learn Taiwanese by James Campbell. The orthography used appears to be slightly modified pe̍h-oē-jī.

- Travlang (language resources for travellers): Hō-ló-oē

- Daiwanway: Tutorial, dictionary, and stories in Taiwanese. Uses a unique romanization system, different from Pe̍h-oē-jī. Includes sound files. The original appears to be offline (last checked 14 November 2007) but is available as a cached version via the Wayback Machine.

- Other

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||