Taenia solium

| Taenia solium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scolex of Taenia solium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Cestoda |

| Order: | Cyclophyllidea |

| Family: | Taeniidae |

| Genus: | Taenia |

| Species: | T. solium |

| Binomial name | |

| Taenia solium Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Taenia solium is the pork tapeworm belonging to cyclophyllid cestodes in the family Taeniidae. It is an intestinal zoonotic parasite found throughout the world, and is most prevalent in countries where pork is eaten. Adult worm is found in humans and has a flat ribbon-like body, which is white in coulour and measures 2 to 3 metres in length. Its distinct head called scolex contains suckers and rostellum as organs of attachment. The main body called strobila consists of a chain of segments known as proglottids. Each proglottid is a complete reproductive unit, hence, the tapeworm is hermaphrodite. It completes its life cycle in human, as definitive host, and pigs, as intermediate host. It is transmitted to pigs through human faeces or contaminated fodder, and to humans through uncooked or undercooked pork. Pigs ingest embryonated eggs called morula which develop into larvae called oncospheres, and ultimately into infective larvae called cysticerci. A cyticercus grows into adult worm in human small intestine. Infection is generally harmless and asymptomatic. However, accidental infection in humans by the larval stage causes cysticercosis. The most severe form is neurocysticersosis, which affects the brain and is a major cause of epilepsy.

Human infection is diagnosed by the parasite eggs in the faeces. For complicated cysticercosis imaging techniques such as computed tomography and NMR are employed. Blood samples can also be tested using antibody reaction of ELISA. Broad spectrum anthelmintics such as praziquantel and albendazole are the most effective medications.

Description

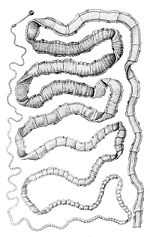

Adult T. solium is a triploblastic acoelomate, having no body cavity. It is normally 2 to 3 m in length, but can become very large, over 8 m long in some situations. It is white in colour and flattened into ribbon-like body. The anterior end is a knob-like head called scolex, which is 1 mm in diameter. The scolex bears four radially arranged suckers (acetabula) that surround the rostellum. These are the organs of attachment to the intestinal wall of the host. The rostellum is armed with two rows of spiny hooks, which are chitinous in nature. There can be 22 to 32 rotelllar hooks, which can be differentiated into short (130 µm) and long (180 µm) types. The elongated body is called strobila, which is connected to the scolex through a short neck. The entire body is covered by a special covering called tegument, which is an absorptive layer consiting of mat of minute hair-like microtriches. The strobila is divided into segments called proglottids. There can be 800-900 proglottids. Body growth starts from neck region so that the oldest proglottids are at the posterior end. Thus there are three distinct proglottids, namely immature proglottids towards the neck, mature proglottids in the middle, and gravid proglottids at the posterior end. A monoecious species, each mature proglottid contains a set of male and female reproductive systems. There are numerous testes and a bilobed ovary, and they open into a common genital pore. The oldest gravid proglottids are full of fertilised eggs,[1][2][3][4]

The infective larave, cysticerci, in human have three morphologically distinct types.[5] The common one is the ordinary "cellulose" cysticercus, which has a fluid-filled bladder 0.5 cm to 1.5 cm in length and an invaginated scolex. The intermediate form has a scolex, while the "racemose" has no evident scolex but is believed to be larger and much more dangerous. They are 20 cm in length and have 60 ml of fluid, and 13% of patients can have all three types in the brain.

Life cycle

T. solium is a digenetic helminth and its life cycle is indirect. It passes through pigs, as intermediate hosts, into humans, as definive hosts. From humans the eggs are released in the environment where they await ingestion by another host. Humans as the definitive hosts are directly infected from contaminated meat.

Definitive host

Humans are infected by the larval stage called cysticercus (cysticercus cellulosae) from a measly pork. A cysticercus is oval-shaped containing inverted scolex (specifically "protoscolex"), which pops out externally once inside the small intestine. This process of evagination is stimulated by bile juice and digestive enzymes of the host. Using the scolex it anchors to the intestinal wall. It grows in size using nutrients from the surrounding. Its strobila lengthens as new proglottids are formed at the neck. In 10–12 weeks after initial infection, it becomes adult worm. As hermaphrodite it reproduces by self-fertilisation, or cross-fertilisation if gametes are exchanged between two different proglottids. Spermatozoan fuses with the ovum in the fertilisation duct, where zygote is produced. The zygote undergoes holoblastic and unequal cleavage resulting in three cell types, small micromeres, medium mesomeres, and large megameres. Megameres develop into syncytial layer called outer embryonic membrane. Mesomeres develop into radially striated inner embryonic membrane or embryophore. Micromeres become the morula. The morula transforms into a six-hooked embryo known as oncosphere, or sometimes hexacanth ("six hooked") larva. A single gravid proglottid can contain more than 50,000 embryonated eggs. Gravid proglottids often rupture in the intestine liberating the eggs in faeces. The intact gravid proglottids are shed off in groups of 4 or 5. The free eggs and detached proglottids are released into the environment through peristalsis. Eggs can survive in the environment for up to two months.[2][6]

Intermediate host

Pigs ingest the eggs from human faeces or vegetation contaminated with human excreta. The embryonated eggs enter the intestine where they hatch into motile oncospheres. The embryonic and basement membranes are removed by the host's digestive enzymes (particularly pepsin). Then the free oncospheres get attached on the intestinal wall using their hooks. With the help of digestive enzymes from the penetration glands, they penetrate the intestinal mucosa to enter blood and lymphatic vessels. They move along the general circulatory system to various organs, and large number are cleared in the liver. The surviving oncospheres preferentially migrate to striated muscles, as well as the brain, liver, and other tissues, where they settle to form cysts called cysticerci. A single cysticercus is spherical measuring 1–2 cm in diameter and contains invaginated protoscolex. The central space is filled with fluid like a bladder, and hence it is also called bladder worm. Cysticerci are usually formed within 70 days and may continue to grow for a year.[7]

Humans are also accidental intermediate hosts when they are infected by embryonated eggs, either by autoinfection or ingestion of contaminated food. As in pigs, the oncospheres hatch, enter blood circulation, and have predilection for brain tissue and other soft muscle tissues. When they settle to form cysts, clinical symptoms of cysticercosis appears. The cysticercus is often called metacestode. If they localize in the brain, serious neurocysticercosis follows.[8][9]

Pathogenesis

Intestinal infection of T. solium is called taeniasis and is quite asymptomatic. Only in severe condition intestinal irritation, anaemia, and indigestion occurs. It can also lead to loss of appetite and emaciation.

Tissue infection called cysticercosis and is clinically pathogenic. Ingestion of T. solium eggs or proglottid rupture within the host intestine can cause larvae to migrate into host tissue to cause cysticercosis. This is the most frequent and severe disease caused by T. solium. In symptomatic cases, a wide spectrum of symptoms may be expressed, including headaches, dizziness and occasional seizures. In more severe cases, dementia or hypertension can occur due to perturbation of the normal circulation of cerebrospinal fluid. (Any increase in intracranial pressure will result in a corresponding increase in arterial blood pressure, as the body seeks to maintain circulation to the brain.) The severity of cysticercosis depends on location, size and number of parasite larvae in tissues, as well as the host immune response. Other symptoms include sensory deficits, involuntary movements, and brain system dysfunction. In children, ocular location of cysts is more common than cystation in other locations of the body.[8]

In many cases cysticercosis occurs in the brain and is called neurocysticercosis, which in turn can lead to epilepsy, seizures, lesions in the brain, blindness, tumor-like growths, and low eosinophil levels. It is the cause of major neurological problems, such as hydrocephalus, paraplegy, meningitis, convulsions and even death.[10]

Diagnosis

T. solium infection is diagnosed by morphological, immunological and molecular assays. The most direct method is microscopic examination of stool for eggs. This was the only method before 1990s and is still usesul in endemic areas. But the technique is not specific as species of Taenia happen to have similar eggs. Proglottids are histologically analysed mostly by staining with India ink. The number of visible uterine branches can help identify the species; for example T. solium uteri have fewer number (only five to 10) of uterine branches on each side. Identification is simplified when scolices are recovered from stool, since scolex structure is different in different species. Suspected cases are diagnosed from blood sample by using polyclonal antibodies that are detected by ELISA. Radioactivey labelled probes are also tested with high success, but are expensive and time consuming for mass diagnosis.[7]

In case of human cysticercosis diagnosis is a sensitive problem and requires biopsy of the infected tissue or sophisticated instruments.[11] T. solium eggs and proglottids found in feces, ELISA or PCR diagnose only taeniasis and not cysticercosis. Radiological tests, such as X-ray, CT scans which demonstrate "ring-enhancing brain lesions", and MRIs, can also be used to detect diseases. X-rays are used to identify calcified larvae in the subcutaneous and muscle tissues, and CT scans and MRIs are used to find lesions in the brain.[3][12]

Treatment

Adult T. solium are easily treated with niclosamide, and is most commonly used in taeniasis. However cysticercosis is a complex disease and requires careful medication. Praziquantel (PZQ) is the drug of choice. In neurocysticercosis praziquantel is widely used.[13] Albendazole appears to be more effective and a safe drug for neurocysticercosis.[14][15] In complicated situation a combination of praziquantel, albendazole and steroid (such as corticosteroids to reduces the inflammation) is recommended.[16] In the brain the cysts can be usually found on the surface. Most cases of brain cysts are found by accident, during diagnosis for other ailments. Surgical removals are the only option of complete removal even if treated succesfully with medications.[3]

Prevention and control

The best way to avoid getting tapeworms is to not eat undercooked pork. Moreover, a high level of sanitation and prevention of faecal contamination of pig foods also plays a major role in prevention. Infection can be prevented with proper disposal of human faeces around pigs, cooking meat thoroughly and/or freezing the meat at −10°C for 5 days. For human cysticercosis, dirty hands are attributed to be the primary cause, and especially common among food handlers.[7] Therefore, personal hygiene such as washing one's hands before eating is an effective measure.

Epidemiology

T. solium is found worldwide, but is more common in cosmopolitan areas. Because pigs are intermediate hosts of the parasite, completion of the life cycle occurs in regions where humans live in close contact with pigs and eat undercooked pork. Therefore high prevalences are reported in Mexico, Latin America, India, Pakistan, Manchuria and Southeast Asia. In Europe it is most widespread among Slavic people.[3][17] Cysticercosis is often seen in areas where poor hygiene allows for contamination of food, soil or water supplies. Prevalence rates in the United States have shown immigrants from Mexico, Central and South America and Southeast Asia account for most of the domestic cases of cysticercosis.[18] Taeniasis and cysticercosis are very rare in predominantly Muslim countries, as Islam forbids the consumption of pork. Human cysticercosis is acquired by ingesting T. solium eggs shed in the feces of a human tapeworm carrier via gravid proglottids, so can occur in populations that neither eat pork nor share environments with pigs, although the completion of the life cycle can occur only where humans live in close contact with pigs and eat pork.

In 1990 and 1991, four unrelated members of an Orthodox Jewish community in New York City developed recurrent seizures and brain lesions, which were found to have been caused by T. solium. All of the families had housekeepers from Latin American countries and were were suspected to be source of the infections.[19][20]

See also

- Cysticercosis cutis

- List of parasites

References

- ↑ Pawlowski, Z.S.; Prabhakar, Sudesh (2002). "Taenia solium: basic biology and transmission". In Gagandeep Singh, Sudesh Prabhakar. Taenia solium Cysticercosis from Basic to Clinical Science. Wallingford, Oxon, UK: CABI Pub. pp. 1–14. ISBN 9780851998398.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Carter, Burton J. Bogitsh, Clint E. (2013). Human Parasitology (4th ed. ed.). Amsterdam: Academic Press. pp. 241–244. ISBN 9780124159150.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Gutierrez, Yezid (2000). Diagnostic Pathology of Parasitic Infections with Clinical Correlations (2nd ed. ed.). New York [u.a.]: Oxford University Press. pp. 635–652. ISBN 9780195121438.

- ↑ Willms, Kaethe (2008). "Morphology and Biochemistry of the Pork Tapeworm, Taenia solium". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 8 (5): 375–382. doi:10.2174/156802608783790875. PMID 18393900.

- ↑ Rabiela, MT; Rivas, A; Flisser, A (November 1989). "Morphological types of Taenia solium cysticerci". Parasitology Today 5 (11): 357–359. doi:10.1016/0169-4758(89)90111-7. PMID 15463154.

- ↑ Mayta, Holger (2009). Cloning and Characterization of Two Novel Taenia Solium Antigenic Proteins and Applicability to the Diagnosis and Control of Taeniasis/cysticercosis. ProQuest. pp. 4–12. ISBN 9780549938996.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Garcia, Oscar H. Del Brutto, Hector H. (2014). "Taenia solium: Biological Characteristics and Life Cycle". Cysticercosis of the Human Nervous System. (1., 2014 ed.). Berlin: Springer-Verlag Berlin and Heidelberg GmbH & Co. KG. pp. 11–21. ISBN 978-3-642-39021-0.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Junghanss, Jeremy Farrar, Peter J. Hotez, Thomas (2013). Manson's Tropical Diseases (23rd edition ed.). Oxford: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 820–825. ISBN 9780702053061.

- ↑ Roth, EJ (1926). "Man as the Intermediate Host of the Taenia Solium.". British Medical Journal 2 (3427): 470–1. PMC PMC2523493. PMID 20772764.

- ↑ Flisser, A.; Avila G, Maravilla P, Mendlovic F, León-Cabrera S, Cruz-Rivera M, Garza A, Gómez B, Aguilar L, Terán N, Velasco S, Benítez M, Jimenez-Gonzalez DE (2010). "Taenia solium: current understanding of laboratory animal models of taeniosis". Parasitology 137 (03): 347. doi:10.1017/S0031182010000272. PMID 20188011.

- ↑ Richards F, Jr; Schantz, PM (1991). "Laboratory diagnosis of cysticercosis.". Clinics in Laboratory Medicine 11 (4): 1011–28. PMID 1802519.

- ↑ Webbe, G. (1994). "Human cysticercosis: Parasitology, pathology, clinical manifestations and available treatment". Pharmacology & Therapeutics 64 (1): 175–200. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(94)90038-8. PMID 7846114.

- ↑ Pawlowski, Zbigniew S. (2006). "Role of chemotherapy of taeniasis in prevention of neurocysticercosis". Parasitology International 55: S105–S109. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.017. PMID 16356763.

- ↑ Garcia HH, Pretell EJ, Gilman RH, Martinez SM, Moulton LH, Del Brutto OH, Herrera G, Evans CA, Gonzalez AE, Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru. (2004). "A trial of antiparasitic treatment to reduce the rate of seizures due to cerebral cysticercosis". N Engl J Med. 350 (3): 249–258. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa031294. PMID 14724304.

- ↑ Matthaiou DK, Panos G, Adamidi ES, Falagas ME. (2008). "Albendazole versus Praziquantel in the Treatment of Neurocysticercosis: A Meta-analysis of Comparative Trials". In Carabin, Hélène. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2 (3): e194. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000194. PMC 2265431. PMID 18335068.

- ↑ "Taeniasis/Cysticercosis". World Health Organization. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ↑ Hansen, NJ; Hagelskjaer, LH; Christensen, T (1992). "Neurocysticercosis: a short review and presentation of a Scandinavian case.". Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases 24 (3): 255–62. PMID 1509231.

- ↑ Flisser A. (May 1988). "Neurocysticercosis in Mexico". Parasitology Today 4 (5): 131–137. doi:10.1016/0169-4758(88)90187-1. PMID 15463066.

- ↑ Dworkin, Mark S. (2010). Outbreak Investigations Around the World: Case Studies in Infectious Disease. Jones and Bartlett Publishers. pp. 192–196. ISBN 978-0-7637-5143-2. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- ↑ Schantz, Moore, Anne C. et al. (September 3, 1992). "Neurocysticercosis in an Orthodox Jewish Community in New York City". New England Journal of Medicine 327 (10): 692–695. doi:10.1056/NEJM199209033271004.

External links

- Taenia solium Genome Project - UNAM

- Taeniasis image library at DPD

- Cysticercosis image library at DPD

- Taeniasis at Stanford

- Taenia solium at Bioweb

- Parasites in Humans

- ZicodeZoo

- BioLib

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||