Szmul Zygielbojm

| Szmul Zygielbojm | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 21, 1895 Borowica, Russian Empire |

| Died | May 12, 1943 (aged 48) London, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Political party | Bund |

| Ethnicity | Jewish |

Szmul Zygielbojm[1] (Polish: [ˈʂmul zɨˈɡʲɛlbɔjm]; Yiddish: שמואל זיגלבוים; February 21, 1895 – May 12, 1943) was a Jewish-Polish socialist politician, leader of the Bund, and a member of the National Council of the Polish government in exile. He committed suicide to protest the indifference of the Allied governments in the face of the Holocaust.

Early years

Szmul Zygielbojm was born on February 21, 1895 in the village of Borowica, Poland (then under control of the Russian Empire). His family moved to Krasnystaw in 1899. Due to poverty, he left school and began working in a factory at the age of 10. Zygielbojm left home for Warsaw when he was 12, but he returned to Krasnystaw at the beginning of World War I and moved with his family to Chełm.[2]

Between the wars

In his 20s, Zygielbojm became involved in the Jewish labor movement, and in 1917 he represented Chełm at the first Bundist convention in Poland. Zygielbojm so impressed the Bund leadership at the convention that he was invited to Warsaw in 1920 to serve as secretary of the Trade Union of Jewish Metal Workers and a member of the Warsaw Committee of the Bund. In 1924 he was elected to the Bund's Central Committee, a position he held until his death.[3]

By 1930, Zygielbojm was editing the Jewish labor unions' journal, Arbeiter Fragen ("Worker’s Issues"). In 1936, the Central Committee sent him to Łódź to lead the Jewish workers' movement, and in 1938 he was elected to the Łódź city council.[2]

| Part of a series on the |

| Jewish Labour Bund |

|---|

|

| 1890s to World War I |

| Interwar years and World War II |

| After 1945 |

|

| People |

|

| Press |

|

| Associated organisations |

| Splinter groups |

|

| Categories |

|

Nazi occupation of Poland

After Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Zygielbojm returned to Warsaw, where he participated in the defense committee during the siege and defense of the city. When the Nazis occupied Warsaw, they demanded 12 hostages from the population to prevent further resistance. Stefan Starzyński, the city's president, proposed that the Jewish labor movement provide a hostage, Ester Ivinska. Zygielbojm volunteered in her place.[3]

On his release, Zygielbojm was made a member of the Jewish Council, or Judenrat, that the Nazis had created. The Nazis ordered the Judenrat to begin the creation of a ghetto within Warsaw. Because of Zygielbojm's public opposition to the order, his fellow Bundists feared for his safety and arranged for his escape from Poland. In December 1939, Zygielbojm reached Belgium. Early in 1940, he spoke before a meeting of the Labour and Socialist International in Brussels and described the early stages of the Nazi persecution of Polish Jewry.[2]

When the Nazis invaded Belgium in May 1940, Zygielbojm went to France and then the United States, where he spent a year and a half trying to convince Americans of the dire situation facing the Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland. In March 1942, he arrived in London to join the National Council of the Polish government in exile, where he was one of two Jewish members (the other was Zionist Ignacy Schwarzbart). In London, Zygielbojm continued to speak publicly about the fate of Polish Jews, including a meeting of the British Labour Party and a speech broadcast on BBC Radio on June 2, 1942.[2]

Jan Karski and the Warsaw Ghetto

In the middle of 1942, Jan Karski, who had been serving as a courier between the Polish underground and the Polish government in exile, was smuggled into the Warsaw Ghetto. One of his guides in the ghetto was Leon Feiner who, like Zygielbojm, belonged to the Bund. Karski asked Feiner what prominent American and British Jews should do. "Tell the Jewish leaders," Feiner said, "that ... they must find the strength and courage to make sacrifices no other statesmen have ever had to make, sacrifices as painful as the fate of my dying people, and as unique."[4]

In the months following his return from Warsaw, Karski reported to the Polish, British and American governments on the situation in Poland, especially the Warsaw Ghetto and the Bełżec death camp, which he had visited secretly. (It is now believed that Karski actually had seen the Izbica Lubelska "sorting camp" where Jews were held until they could be sent to Bełżec, and not Bełżec itself.) Newspaper accounts based on Karski's reports were published by The New York Times on November 25 and November 26 and The Times of London on December 7.[5]

In December, Karski described the conditions in the ghetto to Zygielbojm. Zygielbojm asked whether Karski had any messages from the Jews in the ghetto. As Karski later wrote, he passed along Feiner's message:

This is what they want from their leaders in the free countries of the world, this is what they told me to say: "Let them go to all the important English and American offices and agencies. Tell them not to leave until they obtain guarantees that a way has been decided upon to save the Jews. Let them accept no food or drink, let them die a slow death while the world is looking on. Let them die. This may shake the conscience of the world."[4]

Two weeks later, Zygielbojm spoke again on BBC Radio concerning the fate of the Jews of Poland. "It will actually be a shame to go on living," he said, "if steps are not taken to halt the greatest crime in human history."[6]

The Allies' inaction and Zygielbojm's suicide protest

On April 19, 1943, the Allied governments of the United Kingdom and the United States met in Bermuda, ostensibly to discuss the situation of the Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe. By coincidence, that same day the Nazis attempted to liquidate the remaining Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto and were met with unexpected resistance.

By the beginning of May, the futility of the Bermuda Conference had become apparent.[7] Days later, Zygielbojm received word of the suppression of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the final liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto. He learned his wife Manya and 16-year-old son Tuvia had been killed there. On May 12, Zygielbojm killed himself as a protest against the indifference and inaction of the Allied governments in the face of the Holocaust.

In his "suicide letter," addressed to Polish president Władysław Raczkiewicz and prime minister Władysław Sikorski, Zygielbojm stated that while the Nazis were responsible for the murder of the Polish Jews, the Allies also were culpable:

The responsibility for the crime of the murder of the whole Jewish nationality in Poland rests first of all on those who are carrying it out, but indirectly it falls also upon the whole of humanity, on the peoples of the Allied nations and on their governments, who up to this day have not taken any real steps to halt this crime. By looking on passively upon this murder of defenseless millions tortured children, women and men they have become partners to the responsibility.

I am obliged to state that although the Polish Government contributed largely to the arousing of public opinion in the world, it still did not do enough. It did not do anything that was not routine, that might have been appropriate to the dimensions of the tragedy taking place in Poland....

I cannot continue to live and to be silent while the remnants of Polish Jewry, whose representative I am, are being murdered. My comrades in the Warsaw ghetto fell with arms in their hands in the last heroic battle. I was not permitted to fall like them, together with them, but I belong with them, to their mass grave.

By my death, I wish to give expression to my most profound protest against the inaction in which the world watches and permits the destruction of the Jewish people.[8]

He wished his letter to be known not only by the Polish President and prime minister in exile. He wrote: "I am certain that the President and the Prime Minister will send out these words of mine to all those to whom they are addressed, and that the Polish Government will embark immediately on diplomatic action and explanation of the situation, in order to save the living remnant of the Polish Jews from destruction."

After his death, Zygielbojm's seat in the Polish exile parliament was overtaken by Emanuel Scherer.[9]

Remembering Zygielbojm

In May 1996, a plaque in memory of Zygielbojm was dedicated on the corner of Porchester Road and Porchester Square in London, near Zygielbojm's home.[10] The creation of the memorial had been a joint project of the Bund and the Jewish Socialists' Group. Among those who participated in the memorial's unveiling were members of Zygielbojm's family, the Polish ambassador, and the mayor of Westminster. Every May, supporters of the Szmul Zygielbojm Memorial Committee gather at the memorial.[11][12]

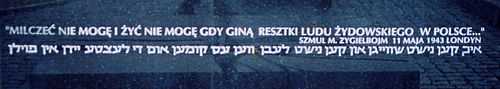

A granite memorial to Zygielbojm was incorporated in the construction of the building at 5 S. Dubois Street[13] in Muranów, a housing project built after the war on the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto.[14] The monument, which is visible from Ulica Zamenhofa (formerly known as Ulica Żydowska, "Jewish Street"[15]), is made up of three elements: an image of faceless people, a broken stone or tablet in front of the memorial, and an inscription in Polish and Yiddish. The engraved words are an unfinished sentence excerpted from Zygielbojm's suicide letter: "I cannot stay silent and I cannot live while the remnants of the Polish Jewry are dying...."[16]

Zygielbojm's body was cremated in symbolic protest and unity with the murdered millions of the Holocaust. In 1959, his surviving son located the cremains in a shed in the Jewish cemetery of Golder's Green in London. Because Zygielbojm had been cremated, the religious community would not permit his ashes to be buried in a Jewish cemetery. With the assistance of the American Jewish labor movement, Zygielbojm's cremains were brought to the U.S. In 1961, his cremains were interred in an honored ceremony before a respectful assemblage of 3,000 at the New Mt. Carmel Cemetery in Ridgewood, New York, beneath a dignified funerary monument. His grave is located at the far side of the cemetery, opposite the entrance. The six-sided monument of pink-hued stone is about five feet high. It is surmounted by an eternal flame in stone. Three of the sides quote from Zygielbojm's suicide letter in Hebrew, English, and Yiddish: "My comrades in the Warsaw Ghetto fell with arms in their hands in their last heroic battle. It was not given to me to die together with them, but I belong to them and to their mass graves. By my death I wish to express my strongest protest against the passivity with which the world observes and permits the extermination of the Jewish people."[17]

Zygielbojm is the subject of a 2001 Polish documentary film titled Śmierć Zygelbojma ("The Death of Zygielbojm").[18] The film, which was directed by Dżamila Ankiewicz, won a special mention at the Kraków Film Festival.

In 2008, a plaque was added to the building in Chełm where Zygielbojm lived. Marek Edelman, a fellow Bundist, wrote a letter that was read at the plaque's dedication.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ sometimes spelled Zygelbojm or Zigelboim

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Szmul Mordekhai Zygielbojm," Aktion Reinhard Camps.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 R. Henes, Shmuel Mordekhai (Arthur) Zigelboim, Commemoration Book Chelm (Translation of Yisker-bukh Chelm, published in Yiddish in Johannesburg, 1954), pp. 287-294.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Jan Karski, Story of a Secret State, pp. 42-50.

- ↑ "What was known, what was done by the Allies," Aktion Reinhard Camps.

- ↑ E. Thomas Wood and Stanislaw M. Jankowski, Believing the Unbelievable, Karski: How One Man Tried to Stop the Holocaust (1994).

- ↑ "To 5,000,000 Jews in the Nazi Death-Trap, Bermuda was a Cruel Mockery," The New York Times, May 4, 1943, p. 17.

- ↑ The Last Letter From Szmul Zygielbojm, The Bund Representative With The Polish National Council In Exile, May 11, 1943.

- ↑ Minczeles, Henri. Histoire générale du Bund: un mouvement révolutionnaire juif. Paris: Editions Austral, 1995. p. 424

- ↑ City of Westminster green plaques http://www.westminster.gov.uk/services/leisureandculture/greenplaques/

- ↑ Małgorzata Zglińska, "I bid farewell to everybody and everything that was dear to me and that I have loved," May 16, 2004.

- ↑ Szmul Zygielbojm Memorial Committee

- ↑ Historical Sites of Jewish Warsaw

- ↑ Jacek Leociak, From Żydowska Street to Umschlagplatz, p. 4.

- ↑ Jacek Leociak, From Żydowska Street to Umschlagplatz, p. 2.

- ↑ Memorial to Shmuel Zygielbojm, Ulica Zamenhofa

- ↑ Alvin Poplack, Carved in Granite: Holocaust Memorials in Greater New York Jewish Cemeteries (New York: Jay Street, 2008), pp. 48-50.

- ↑ Śmierć Zygelbojma, Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ (Polish) Szmul Zygielbojm upamiętniony w Chełmie, Rzeczpospolita, September 25, 2008.

External links

- The Last Letter From Szmul Zygielbojm, The Bund Representative With The Polish National Council In Exile, May 11, 1943

- Suicide telegram sent to Emanuel Nowogrodski, now at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York

- Ruwin Zigelboim, Al Kiddush HaShem [In the sanctification of God's name], Dedicated to the Illustrious Memory of my brother, Shmuel Mordekhai (Arthur) Zigelboim, Commemoration Book Chelm (Translation of Yisker-bukh Chelm, published in Yiddish in Johannesburg, 1954), pp. 295–302.

- Photograph of the Warsaw memorial wall, daytime

- Photograph of the Warsaw memorial wall at night

- Photograph of the tablet in front of the Warsaw memorial wall

- Photograph of London memorial plaque

- Photograph of the dedication of the London memorial plaque

- Photograph of Zygielbojms gravestone at the Mt Carmel Cemetery, Queens, NY

- Szmul Mordekhai "Artur" Zygielbojm, The Terrible Choice: Some Contemporary Jewish Responses to the Holocaust.]

- Papers of Shmuel Mordkhe (Artur) Zygielbojm.; RG 1454; YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York, NY.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||