Surplus killing

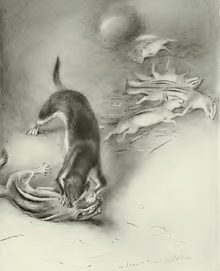

Surplus killing is a common behavior exhibited by predators, in which they kill more prey than they can immediately eat and then cache or abandon the remainder. For example, researchers in Canada's Northwest Territories once found the bodies of 34 neonatal caribou calves that had been killed by wolves and scattered, some half-eaten and some completely untouched, over three square kilometres.[1] In Australia, over several days a single fox once killed eleven wallabies and 74 penguins, eating almost none. Up to 19 spotted hyenas once killed 82 Thomson's gazelle and badly injured 27, eating just 16%.[2]

Surplus killing has been observed among zooplankton, damselfly naiads, predaceous mites, weasels, honey badgers, wolves, orcas, red foxes, leopards, lions, spotted hyenas, spiders, brown and black and polar bears, coyotes, lynx, mink, raccoons, dogs and house cats.

In surplus killing predators eat only the most-preferred animals and animal parts. Bears engaging in surplus killing of salmon are likelier to eat unspawned fish because of their higher muscle quality, and high-energy parts such as brains and eggs.[2]

Surplus killing can deplete the overall food supply, waste predator energy and risk them being injured. Nonetheless, researchers say animals surplus kill whenever they can, in order to procure food for offspring and others, to gain valuable killing experience, and to create the opportunity to eat the carcass later when they are hungry again.[2][3]

There are many documented examples of animals caching surplus kills. For example, in late fall least weasels often surplus kill vole and then dig them up and eat them on winter days when it is too cold to hunt.[2] Surplus killing by wolves has mainly been observed when snow is unusually deep in late winter or early spring, and the wolves have frequently cached their prey for eating days or weeks later. On February 7 1991 in Denali National Park, six wolves killed at least 17 caribou and left many untouched. By February 12, 30–95% of each carcass had been eaten or cached, and by April 16, several had been dug up and fed upon again.[4]

Surplus killing is also known as "excessive killing" and "henhouse syndrome".[2][5] The term was invented by Dutch biologist Hans Kruuk after studying spotted hyenas in Africa[6] and red foxes in England.[7]

See also

- Bison hunting

- Collateral damage

- Overfishing

References

- ↑ Mech, edited by L. David; Boitani, Luigi (2003). Wolves: behavior, ecology, and conservation. Chicago [u.a.]: Univ. of Chicago Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780226516967.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Mills, L. Scott. Conservation of wildlife populations: demography, genetics, and management (2nd ed. ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 148. ISBN 9780470671504.

- ↑ Hansen, Kevin (2006). Bobcat: master of survival ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 0195183037.

- ↑ Moskowitz, David. Wolves in the Land of Salmon. Timber Press. p. 145. ISBN 1604692278.

- ↑ Moskowitz, David. Wolves in the Land of Salmon. Timber Press. p. 144. ISBN 1604692278.

- ↑ Kruuk, Hans (1972). The Spotted Hyena: A study of predation and social behaviour. p. 335. ISBN 0-563-20844-9.

- ↑ Macdonald, David (1987). Running with the Fox. p. 224. ISBN 0-04-440199-X.

Bibliography

- Jennifer L. Maupin and Susan Reichert, Superfluous killing in spiders.

- Joseph K. Gaydos, Stephen Raverty,Robin W. Baird, and Richard W. Osborne, SUSPECTED SURPLUS KILLING OF HARBOR SEAL PUPS (PHOCA VITULINA) BY KILLER WHALES (ORCINUS ORCA).

- William G. George and Timothy Kimmel, A Slaughter of Mice by Common Crows.

- Wildlife Online: Foxes-Surplus Killing, Why do foxes kill to excess....

- For Wolves: Ralph Maughan Wolf Report, Jackson Trio makes some surplus kills.

- High Country News, Zachary Smith, Wolf pack wiped out for ‘surplus killing’.

- Victor Van Ballenberghe, Technical Information on Wolf Ecology and Wolf/Prey Relationships.

- Ned Rozell, Far North Grizzlies Develop Taste for Muskoxen.

- Pierre-Yves Daoust, Andrew Boyne, Ted D’Eon, Surplus killing of Roseate Terns and Common Terns by a mink.