Siraj ud-Daulah

| Siraj ud-Daulah | |

|---|---|

|

Mansur-ul-Mulk (Victory of the Country) Siraj ud-Daulah (Light of the State) Hybut Jang (Horror in War) | |

Siraj ud-Daulah | |

| Reign | 1756–1757 |

| Full name | Mirza Muhammad Siraj ud-Daulah |

| Titles | Nawab Nazim of Bengal, Bihar and Odisha (Nawab of Bengal) |

| Born | 1733 |

| Died | July 2, 1757 |

| Buried | Khushbagh, Murshidabad |

| Predecessor | Ali Vardi Khan |

| Successor | Mir Jafar |

| Wives |

Umdat-un-nisa (Bahu Begum Sahiba) (m. before 22 March 1745; d. 10 November 1793) Lutf-un-nisa (Raj Kanwar) (d. November 1790) |

| Issue | Qudsia Begum Sahiba (born at Mansurganj Palace near Murshidabad before July 23, 1754; m. Mir Asad Ali Khan Bahadur) (d/o Lutf-un-nisa) |

| Dynasty | Afshar |

| Father | Zain ud-Din Ahmed Khan (Mirza Muhammad Hashim) |

| Mother | Amina Begum |

| Religious beliefs | Islam |

Mirza Muhammad Siraj ud-Daulah (Urdu: میرزا محمد سراج الدولہ, Bengali: নবাব সিরাজ উদ-দাউলা), more commonly known as Siraj ud-Daulah (1733 – July 2, 1757), was the last independent Nawab of Bengal. The end of his reign marked the start of British East India Company rule over Bengal and later almost all of South Asia. He was sometimes called, and his name rendered, "Sir Roger Dowler" or "Sir Roger Dowlah" by some of his British contemporaries, and "Sau Raja Dowla" by John Holwell. However these distorted early English renderings, among others like "Seapoy", were rebuked and ridiculed by later writers.[1]

Early years

Siraj was born to Zain ud-Din Ahmed Khan (Mirza Muhammad Hashim) and Amina begum in 1733, and soon after his birth, Siraj's maternal grandfather, Alivardi Khan was appointed as the Deputy Governor of Bihar. Amina Begum was the youngest daughter of Nawab Ali Vardi Khan. Since Ali Vardi had no son, Siraj, as his grandson, became very close to him and since his childhood was seen by many as Alivardi's successor. Accordingly, he was raised at the Nawab's palace with all necessary education and training suitable for a future Nawab. Young Siraj also accompanied Alivardi in his military ventures against the Marathas in 1746. So, Siraj was regarded as the "fortune child" of the family. Since, Siraj's birth he was loved by his grandfather, with a special affection towards Siraj.

In May 1752, Alivardi Khan declared Siraj as his successor. During the last years of Alivardi Khan's reign the death of some family members affected Alivardi both mentally and physically. Alivardi Khan died of dropsy on April 9, 1756 at the age of eighty or above. Before dying Alivardi advised Siraj to secure the well being of his province by removing all evils and disorders. Luke Scraton (One of the directors of the British East India Company from 1765–1768) says that Siraj swore on the Quran at Alivardi's death bed that after that in future he would never touch any intoxicating liquor, and he kept the promise ever after. Siraj also faced many enemies during his short reign (April 1756 – July 1757) both from his family and outside as well.

During Alivardi Khan's reign Siraj also built the Hirajheel (Diamond Lake)and the Hirajheel Palace, which is also known as the "Mansurganj" Palace. He built it as he was very jealous of Ghaseti Begum's (his maternal aunt's) Motijheel (Pearl Lake) and the Motijheel Palace.

Reign as Nawab

Siraj succeeded Alivardi Khan as the Nawab in April 1756 at the age of 23, under the titles of Mansur-ul-Mulk (Victory of the Country), Siraj ud-Daulah (Light of the State) and Hybut Jang (Horror in War). Siraj-ud-Daulah's nomination to the Nawabship aroused the jealousy and enmity of his maternal aunt, Ghaseti Begum (Mehar-un-nisa Begum), Raja Rajballabh, Mir Jafar and Shaukat Jung (Siraj's cousin). Ghaseti Begum possessed huge wealth, which was the source of her influence and strength. Apprehending serious opposition from her, Siraj ud-Daulah seized her wealth from Motijheel Palace and placed her in confinement. The Nawab also made changes in high government positions giving them his own favourites. Mir Mardan was appointed Bakshi (Paymaster of the army) in place of Mir Jafar. Mohanlal was elevated to the post of peshkar of his Dewan Khana and he exercised great influence in the administration. Eventually Siraj suppressed Shaukat Jang, governor of Purnia, who was killed in a clash.

Black Hole of Calcutta

Siraj, as the direct political disciple of his grandfather, was aware of the global British interest in colonization and hence, resented the British politico-military presence in Bengal represented by the British East India Company. He was annoyed at the company's alleged involvement with and instigation of some members of his own court in a conspiracy to oust him. His charges against the company were mainly threefold. Firstly, that they strengthened the fortification around the Fort William without any intimation and approval; secondly, that they grossly abused the trade privileges granted to them by the Mughal rulers, which caused heavy loss of customs duties for the government; and thirdly, that they gave shelter to some of his officers, for example Krishnadas, son of Rajballav, who fled Dhaka after misappropriating government funds. Hence, when the East India Company started further enhancement of military preparedness at Fort William in Calcutta, Siraj asked them to stop. The Company did not heed his directives, so Siraj-ud Daulah retaliated and captured Kolkata (Shortly renamed as Alinagar) from the British in June 1756.The Nawab gathered his forces together and took Fort William. The captives numbered 64 to 69 people, and they were placed in the cell as a temporary holding by a local commander. But there was confusion in the Indian chain of command, and the captives were unintentionally left there overnight. No more than 43 of the garrison at Fort William was unaccounted for afterwards; therefore, at most 43 people died in the Black Hole.The British—at the very least Holwell and other East India Company officials who knew the truth—did overstate what happened, exaggerating the number of casualties and the motivations of the Indians. On the other hand, the Indians did force over five dozen people into a cell that was designed to hold maybe six, and then promptly, though accidentally, forgot about them and let them swelter and starve.[2]

Sir William Meredith, during the Parliamentary inquiry into Robert Clive's actions in India, vindicated Siraj ud-Daulah of any charges surrounding the Black Hole incident: A peace was however agreed upon with Siraj ud -Dowlah, who generously condoned and pardoned the aggressive excesses of the officials and subordinates of the British East India Company, towards the authority and power of the Nawab Of Bengal.And the persons who went as ambassadors to confirm that peace, formed a conspiracy, by which he was deprived of his kingdom and his life.[3]

The Conspiracy

The Nawab was infuriated on learning of the attack on Chandernagar. His former hatred of the British returned, but he now felt the need to strengthen himself by alliances against the British. The Nawab was plagued by fear of attack from the north by the Afghans under Ahmad Shah Durrani and from the west by the Marathas. Therefore, he could not deploy his entire force against the British for fear of being attacked from the flanks. A deep distrust set in between the British and the Nawab. As a result, Siraj started secret negotiations with Jean Law, chief of the French factory at Cossimbazar, and de Bussy. The Nawab also moved a large division of his army under Rai Durlabh to Plassey, on the island of Cossimbazar 30 miles (48 km) south of Murshidabad.[4][5][6][7]

Popular discontent against the Nawab flourished in his own court. The Seths, the traders of Bengal, were in perpetual fear for their wealth under the reign of Siraj, contrary to the situation under Alivardi’s reign. They had engaged Yar Lutuf Khan to defend them in case they were threatened in any way.[8] William Watts, the Company representative at the court of Siraj, informed Clive about a conspiracy at the court to overthrow the ruler. The conspirators included Mir Jafar, the paymaster of the army, Rai Durlabh, Yar Lutuf Khan and Omichund (Amir Chand), a Sikh merchant, and several officers in the army.[9] When communicated in this regard by Mir Jafar, Clive referred it to the select committee in Calcutta on 1 May. The committee passed a resolution in support of the alliance. A treaty was drawn up between the British and Mir Jafar to raise him to the throne of the Nawab in return for support to the British in the field of battle and the bestowal of large sums of money upon them as compensation for the attack on Calcutta. On May 2, Clive broke up his camp and sent half the troops to Calcutta and the other half to Chandernagar.[10][11][12][13]

Mir Jafar and the Seths desired that the confederacy between the British and himself be kept secret from Omichund, but when he found out about it, he threatened to betray the conspiracy if his share was not increased to three million rupees (£ 300,000). Hearing of this, Clive suggested an expedient to the Committee. He suggested that two treaties be drawn – the real one on white paper, containing no reference to Omichund and the other on red paper, containing Omichund’s desired stipulation, to deceive him. The Members of the Committee signed on both treaties, but Admiral Watson signed only the real one and his signature had to be counterfeited on the fictitious one.[14] Both treaties and separate articles for donations to the army, navy squadron and committee were signed by Mir Jafar on 4 June.[15][16][17][18]

Lord Clive testified and defended himself thus before the House of Commons of Parliament on May 10, 1773, during the Parliamentary inquiry into his conduct in India:

"Omichund, his confidential servant, as he thought, told his master of an agreement made between the English and Monsieur Duprée [may be a mistranscription of Dupleix] to attack him, and received for that advice a sum of not less than four lacks of rupees. Finding this to be the man in whom the nabob entirely trusted, it soon became our object to consider him as a most material engine in the intended revolution. We therefore made such an agreement as was necessary for the purpose, and entered into a treaty with him to satisfy his demands. When all things were prepared, and the evening of the event was appointed, Omichund informed Mr. Watts, who was at the court of the nabob, that he insisted upon thirty lacks of rupees, and five per cent. upon all the treasure that should be found; that, unless that was immediately complied with, he would disclose the whole to the nabob; and that Mr. Watts, and the two other English gentlemen then at the court, should be cut off before the morning. Mr. Watts, immediately on this information, dispatched an express to me at the council. I did not hesitate to find out a stratagem to save the lives of these people, and secure success to the intended event. For this purpose we signed another treaty. The one was called the Red, the other the White treaty. This treaty was signed by every one, except admiral Watson; and I should have considered myself sufficiently authorised to put his name to it, by the conversation I had with him. As to the person who signed admiral Watson's name to the treaty, whether he did it in his presence or not, I cannot say; but this I know, that he thought he had sufficient authority for so doing. This treaty was immediately sent to Omichund, who did not suspect the stratagem. The event took place, and success attended it; and the House, I am fully persuaded, will agree with me, that, when the very existence of the Company was at stake, and the lives of these people so precariously situated, and so certain of being destroyed, it was a matter of true policy and of justice to deceive so great a villain."[19][20]

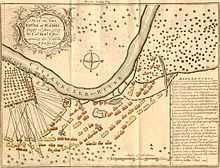

The Battle of Plassey

The Battle of Plassey (or Palashi) is widely considered the turning point in the history of India, and opened the way to eventual British domination. After Siraj-Ud-Daulah's conquest of Calcutta, the British sent fresh troops from Madras to recapture the fort and avenge the attack. A retreating Siraj-Ud-Daulah met the British at Plassey. Siraj-ud-Daulah had to make camp 27 miles away from Murshidabad. On 23 June 1757 Siraj-Ud-Daulah called on Mir Jafar because he was saddened by the sudden fall of Mir Mardan who was a very dear companion of Siraj in battles. The Nawab asked for help from Mir Jafar. Mir Jafar advised Siraj to retreat for that day. The Nawab made the blunder in giving the order to stop the war. Following his command, the soldiers of the Nawab were returning to their camps. At that time, Robert Clive attacked the soldiers with his army. At such a sudden attack, the army of Siraj became indisciplined and could think of no way to fight. So all fled away in such a situation. Betrayed by a conspiracy plotted by Jagat Seth, Mir Jafar, Krishna Chandra, Umi Chand etc., he lost the battle and had to escape. He went first to Murshidabad and then to Patna by boat, but was eventually arrested by Mir Jafar's soldiers. Siraj-ud-Daulah was executed on July 2, 1757 by Mohammad Ali Beg under orders from Mir Miran, son of Mir Jafar in Namak Haram Deorhi.

The character of Siraj ud-Daulah

Siraj ud-Daulah is usually seen as a freedom fighter in modern India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan for his opposition to the beginning of British rule over India.[citation needed] As a teenager, he led a reckless life, which came to the notice of his grandfather. But keeping a promise he made to his grandfather on his deathbed, he gave up gambling and drinking alcohol completely after taking the title Nawab of Bengal.

Young Siraj ud-Daulah was of olive skin complexion, he was slim and tall and kept shoulder-length black hair, he wore the finest silk and cotton, Kaftans and Sherwanis; he is known to have been hostile to his most devoted advisers, he blindly trusted very few people and often insulted and defamed his foes and rivals including the British.

"Siraj-ud-daula has been pictured," says the biographer of Robert Clive, "as a monster of vice, cruelty and depravity."

In 1778, Robert Orme wrote of the relationship of Siraj ud-Daulah to his maternal grandfather Alivardi Khan:

Mirza Mohammed Siraj, a youth of seventeen years, had discovered the most vicious propensities, at an age when only follies are expected from princes. But the great affection which Alivardi Khan had borne to the father was transferred to this son, whom he had for some years bred in his own palace; where instead of correcting the evil dispositions of his nature, he suffered them to increase by overweening indulgence: taught by his minions to regard himself as of a superior order of being, his natural cruelty, hardened by habit, in conception he was not slow, but absurd; obstinate, sullen, and impatient of contradiction; but notwithstanding this insolent contempt of mankind,the confusion of his ideas rendered him suspicious of all those who approached him, excepting his favourites, who were buffoons and profligate men, raised from menial servants to be his companions: with these he lived in every kind of intemperance and debauchery, and more especially in drinking spiritous liquors to an excess, which inflamed his passions and impaired the little understanding with which he was born. He had, however, cunning enough to carry himself with much demureness in the presence of Allaverdy, whom no one ventured to inform of his real character; for in despotic states the sovereign is always the last to hear what it concerns him most to know."

Two Shia historians who were in favor of Mir Jafar , wrote of Siraj ud-Daulah.

Ghulam Husain Salim wrote:

Owing to Siraj ud Dowla’s harshness of temper and indulgence, fear and terror had settled on the hearts of everyone to such an extent that no one among his generals of the army or the noblemen of the city was free from anxiety. Among his officers, whoever went to wait on Siraj ud Dowla despaired of life and honour, and whoever returned without being disgraced and ill-treated offered thanks to God. Siraj ud Dowla treated all the noblemen and capable generals of Alivardi Khan with ridicule and drollery, and bestowed on each some contemptuous nickname that ill-suited any of them. And whatever harsh expressions and abusive epithet came to his lips, Siraj ud Dowla uttered them unhesitatingly in the face of everyone, and no one had the boldness to breath freely in his presence.

Ghulam Husain Tabatabai wrote of Siraj ud-Daulah:

- "Making no distinction between vice and virtue, he carried defilement wherever he went, and, like a man alienated in his mind, he made the house of men and women of distinction the scenes of his depravity, without minding either rank or station. In a little time he became detested as Pharaoh, and people on meeting him by chance used to say, ‘God save us from him!'"

Sir William Meredith, during the Parliamentary inquiry into Robert Clive's actions in India, defended the character of Siraj-ud Daulah:

"Siraj-ud-Daulah is indeed reported to have been a very wicked, and a very cruel prince; but how he deserved that character does not appear in fact. He was very young, not 20 years old when he was put to death—and the first provocation to his enmity was given by the English. It is true, that when he took Calcutta a very lamentable event happened, I mean the story of the Black Hole; but that catastrophe can never be attributed to the intention, for it was without the knowledge of the prince. I remember a similar accident happening in St. Martin's roundhouse; but it should appear very ridiculous, were I, on that account, to attribute any guilt or imputation of cruelty to the memory of the late king, in whose reign it happened. A peace was however agreed upon with Suraj-ud-Daulah; and the persons who went as ambassadors to confirm that peace, formed the conspiracy, by which he was deprived of his kingdom and his life."[3]

See also

- Nawabs of Bengal

- List of rulers of Bengal

- History of Bengal

- History of Bangladesh

- History of India

Notes

- ^ Riyazu-s-salatin, A History of Bengal - a reference to Siraj-Ud-Daul's character may be found[21]

- ^ The Seir Mutaqherin, Vol 2 - a discussion of Sirj-Ud-Daulah's character[22]

References

- ↑ "The Orthography of Indian Words". The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British and Foreign India, China, Australasia. (London: Parbury, Allen, and Co.) XVI: 132. January–April 1835.

- ↑ "Is the "Black Hole of Calcutta" a myth?". Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The Parliamentary history of England from the earliest period to the year 1803. Retrieved August 2012.

- ↑ Harrington, p. 25

- ↑ Mahon, p. 337

- ↑ Orme, p. 145

- ↑ Malleson, pp. 48–49

- ↑ Bengal, v.1, p. clxxxi

- ↑ Bengal, v.1, pp. clxxxiii–clxxxiv

- ↑ Malleson, pp. 49–51

- ↑ Harrington, pp. 25–29

- ↑ Mahon, pp. 338–339

- ↑ Orme, pp. 147–149

- ↑ Bengal, v.1, pp. clxxxvi–clxxxix

- ↑ Orme, pp. 150–161

- ↑ Harrington, p. 29

- ↑ Mahon, pp. 339–341

- ↑ Bengal, v.1, pp. cxcii–cxciii

- ↑ The Parliamentary history of England from the earliest period to the year 1803, Volume 17. p. 876.

- ↑ The gentleman's magazine, and historical chronicle, Volume 43. pp. 630–631.

- ↑ http://erga.packhum.org/persian/pf?file=07601010&ct=64

- ↑ http://erga.packhum.org/persian/pf?file=07501022&ct=28

- Akhsaykumar Moitrayo, Sirajuddaula, Calcutta 1898

- BK Gupta, Sirajuddaulah and the East India Company, 1756–57, Leiden, 1962

- Kalikankar Datta, Sirajuddaulah, Calcutta 1971

External links

- Siraj-ud-daulah at Banglapedia

- Biography in Short

- A Poem on Siraj

- Murshidabad-the Capital of Bengal during the Nawabs

- "Riyazu-s-salatin", A History of Bengal, Ghulam Husain Salim (translated from the Persian): viewable online at the Packard Humanities Institute

- "Seir Mutaquerin", Ghulam Husain Tatabai (translated from the Persian): viewable online at the Packard Humanities Institute

- Siraj in Murshidabad

- Website dedicated to Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah

| Siraj ud-Daulah Born: 1733 Died: 2 July 1757 | ||

| Preceded by Alivardi Khan |

Nawab of Bengal 1756–1757 |

Succeeded by Mir Jafar |

|