Suprematism

Suprematism (Russian: Супремати́зм) was an art movement, focused on basic geometric forms, such as circles, squares, lines, and rectangles, painted in a limited range of colors. It was founded by Kazimir Malevich in Russia, around 1913, and announced in Malevich's 1915 exhibition in St. Petersburg where he exhibited 36 works in a similar style.[1] The term suprematism refers to an abstract art based upon “the supremacy of pure artistic feeling” rather than on visual depiction of objects.[2]

Birth of Suprematism

Kasimir Malevich originated Suprematism when he was an established painter having exhibited in the Donkey's Tail and the Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) exhibitions of 1912 with cubo-futurist works. The proliferation of new artistic forms in painting, poetry and theatre as well as a revival of interest in the traditional folk art of Russia provided a rich environment in which a Modernist culture was born.

In "Suprematism" (Part II of his book The Non-Objective World, which was published 1927 in Munich as Bauhaus Book No. 11), Malevich clearly stated the core concept of Suprematism:

- Under Suprematism I understand the primacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist, the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in which it is called forth.

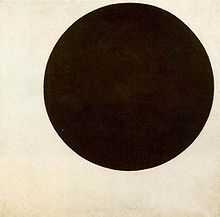

He created a suprematist "grammar" based on fundamental geometric forms; in particular, the square and the circle. In the 0.10 Exhibition in 1915, Malevich exhibited his early experiments in suprematist painting. The centerpiece of his show was the Black Square, placed in what is called the red/beautiful corner in Russian Orthodox tradition; the place of the main icon in a house. "Black Square" was painted in 1915 and was presented as a breakthrough in his career and in art in general. Malevich also painted White on White which was also heralded as a milestone. "White on White" was a breakthrough from polychrome to monochrome Suprematism.

Distinct from Constructivism

Malevich's Suprematism is fundamentally opposed to the postrevolutionary positions of Constructivism and materialism. Constructivism, with its cult of the object, is concerned with utilitarian strategies of adapting art to the principles of functional organization. Under Constructivism, the traditional easel painter is transformed into the artist-as-engineer in charge of organizing life in all of its aspects.

Suprematism, in sharp contrast to Constructivism, embodies a profoundly anti-materialist, anti-utilitarian philosophy. In "Suprematism" (Part II of The Non-Objective World), Malevich writes:

- Art no longer cares to serve the state and religion, it no longer wishes to illustrate the history of manners, it wants to have nothing further to do with the object, as such, and believes that it can exist, in and for itself, without "things" (that is, the "time-tested well-spring of life").

Jean-Claude Marcadé has observed that "Despite superficial similarities between Constructivism and Suprematism, the two movements are nevertheless antagonists and it is very important to distinguish between them." According to Marcadé, confusion has arisen because several artists - either directly associated with Suprematism such as El Lissitzky or working under the suprematist influence as did Rodchenko and Liubov Popova - later abandoned Suprematism for the culture of materials.

Suprematism does not embrace a humanist philosophy which places man at the center of the universe. Rather, Suprematism envisions man - the artist - as both originator and transmitter of what for Malevich is the world's only true reality - that of absolute non-objectivity.

...a blissful sense of liberating non-objectivity drew me forth into a "desert", where nothing is real except feeling... ("Suprematism", Part II of The Non-Objective World)

For Malevich, it is upon the foundations of absolute non-objectivity that the future of the universe will be built - a future in which appearances, objects, comfort, and convenience no longer dominate.

Influences on the movement

Malevich also credited the birth of suprematism to Victory Over the Sun, Kruchenykh's Futurist opera production for which he designed the sets and costumes in 1913. One of the drawings for the backcloth shows a black square divided diagonally into a black and a white triangle. Because of the simplicity of these basic forms they were able to signify a new beginning.

Another important influence on Malevich were the ideas of the Russian mystic-mathematician, philosopher, and disciple of Georges Gurdjieff; P. D. Ouspensky who wrote of "a fourth dimension or a Fourth Way beyond the three to which our ordinary senses have access".[3]

Some of the titles to paintings in 1915 express the concept of a non-Euclidean geometry which imagined forms in movement, or through time; titles such as: Two dimensional painted masses in the state of movement. These give some indications towards an understanding of the Suprematic compositions produced between 1915 and 1918.

Association

The Supremus group, which in addition to Malevich included Aleksandra Ekster, Olga Rozanova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Ivan Kliun, Liubov Popova, Nikolai Suetin, Ilya Chashnik, Nina Genke-Meller, Ivan Puni and Ksenia Boguslavskaya, met from 1915 onwards to discuss the philosophy of Suprematism and its development into other areas of intellectual life. Lissitzky spread Suprematist ideas abroad in the early 1920s, but Malevich himself announced the end of Suprematism in 1922.[1]

Architecture

Nikolai Suetin used Suprematist motifs on works at the St. Petersburg Lomonosov Porcelain Factory where Malevich and Chashnik were also employed, and Malevich designed a Suprematist teapot. The Suprematists also made architectural models in the 1920s which offered a different conception of socialist buildings to those developed in Constructivist architecture.

Malevich's architectural projects were known after 1922 Arkhitektoniki. Designs emphasized the right angle, with similarities to De Stijl and Le Corbusier, and were justified with an ideological connection to communist governance and equality for all. Another part of the formalism was low regard for triangles which were "dismissed as Ancient, pagan, or Christian".[4]

The first Suprematist Architectural project was created by Lazar Khidekel in 1926. In mid 1920's - 1932 Lazar Khidekel also created a series of futuristic projects such as Aero-City, Garden-City, and City Over Water.

Social context

This development in artistic expression came about when Russia was in a revolutionary state, ideas were in ferment, and the old order was being swept away. As the new order became established, and Stalinism took hold from 1924 on, the state began limiting the freedom of artists. From the late 1920s the Russian avant-garde experienced direct and harsh criticism from the authorities and in 1934 the doctrine of Socialist Realism became official policy, and prohibited abstraction and divergence of artistic expression. Malevich nevertheless retained his main conception. In his self-portrait of 1933 he represented himself in a traditional way — the only way permitted by Stalinist cultural policy — but signed the picture with a tiny black-over-white square.

References and sources

|

|

- References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Honour, H. and Fleming, J. (2009) A World History of Art. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, pp. 793-795. ISBN 9781856695848

- ↑ Malevich, Kazimir (1927). The Non-Objective World. Munich.

- ↑ (Gooding, 2001)

- ↑ Hanno-Walter Kruft, Elsie Callander, Ronald Taylor, and Antony Wood A history of architectural theory: from Vitruvius to the present Edition 4 Publisher Princeton Architectural Press, 2003 ISBN 1-56898-010-8, ISBN 978-1-56898-010-2 706 pages page 416

- ↑ "Art & Context: Monet's Cliff Walk at Pourville and Malevich's White on White". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- Sources

- Kasimir Malevich, The Non-Objective World. English translation by Howard Dearstyne from the German translation of 1927 by A. von Riesen from Malevich's original Russian manuscript, Paul Theobald and Company, Chicago, 1959.

- Camilla Gray, The Russian Experiment in Art, Thames and Hudson, 1976.

- Mel Gooding, Abstract Art, Tate Publishing, 2001.

- Jean-Claude Marcadé, "What is Suprematism?", from the exhibition catalogue, Kasimir Malewitsch zum 100. Geburtstag, Galerie Gmurzynska, Cologne, 1978.

Further reading

- Jean-Claude Marcadé, "Malevich, Painting and Writing: On the Development of a Suprematist Philosophy", Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism, Guggenheim Museum, April 17, 2012 [Kindle Edition]

- Jean-Claude Marcadé, "Some Remarks on Suprematism"; and Emmanuel Martineau, "A Philosophy of the 'Suprema' ", from the exhibition catalogue Suprematisme, Galerie Jean Chauvelin, Paris, 1977

- Miroslav Lamac and Juri Padrta, "The Idea of Suprematism", from the exhibition catalogue, Kasimir Malewitsch zum 100. Geburtstag, Galerie Gmurzynska, Cologne, 1978

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Suprematism. |

- Kazimir Malevich. Suprematism. Manifesto. Online extracts from Malevich' suprematism art manifesto.

| |||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||