Superresolution

Superresolution (SR) is a class of techniques that enhance the resolution of an imaging system. In some SR techniques—termed optical SR—the diffraction limit of systems is transcended, while in others—geometrical SR—the resolution of digital imaging sensors is enhanced.

Basic Concepts

Because some of the ideas surrounding superresolution raise fundamental issues, there is need at the outset to examine the relevant physical and information-theoretical principles.

Diffraction Limit The detail of a physical object that an optical instrument can reproduce in an image has limits that are mandated by laws of physics, whether formulated by the diffraction equations in the wave theory of light[1] or the Uncertainty Principle for photons in quantum mechanics.[2] Information transfer can never be increased beyond this boundary, but packets outside the limits can be cleverly swapped for (or multiplexed with) some inside it.[3] One does not so much “break” as “run around” the diffraction limit. New procedures probing electro-magnetic disturbances at the molecular level (in the so-called near field)[4] remain fully consistent with Maxwell's equations.

A succinct expression of the diffraction limit is given in the spatial-frequency domain. In Fourier Optics light distributions are expressed as superpositions of a series of grating light patterns in a range of fringe widths, technically spatial frequencies. It is generally taught that diffraction theory stipulates an upper limit, the cut-off spatial-frequency, beyond which pattern elements fail to be transferred into the optical image, i.e., are not resolved. But in fact what is set by diffraction theory is the width of the passband, not a fixed upper limit. No laws of physics are broken when a spatial frequency band beyond the cut-off spatial frequency is swapped for one inside it: this has long been implemented in dark-field microscopy. Nor are information-theoretical rules broken when superimposing several bands,:[5][6] disentangling them in the received image needs assumptions of object invariance during multiple exposures, i.e., the substitution of one kind of uncertainty for another.

Information When the term superresolution is used in techniques of inferring object details from statistical treatment of the image within standard resolution limits, for example, averaging multiple exposures, it involves an exchange of one kind of information (extracting signal from noise) for another (the assumption that the target has remained invariant).

Resolution and localization True resolution involves the distinction of whether a target, e.g. a star or a spectral line, is single or double, ordinarily requiring separable peaks in the image. When a target is known to be single, its location can be determined with higher precision than the image width by finding the centroid (center of gravity) of its image light distribution. The word ultra-resolution had been proposed for this process[7] but it did not catch on, and the high-precision localization procedure is typically referred to as superresolution.

In summary: The technical achievements of enhancing the performance of imaging-forming and –sensing devices now classified as superresolution utilize to the fullest but always stay within the bounds imposed by the laws of physics and information theory.

Techniques to which the term Superresolution has been applied

Optical or diffractive superresolution

Substituting spatial-frequency bands. Though the bandwidth allowable by diffraction is fixed, it can be positioned anywhere in the spatial-frequency spectrum. Dark-field illumination in microscopy is an example. See also aperture synthesis.

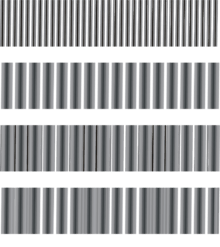

Multiplexing spatial-frequency bands, e.g., structured illumination (see figure on the left). An image is formed using the normal passband of the optical device. Then some known light structure, for example a set of light fringes that is also within the passband, is superimposed on the target.[6] The image now contains components resulting from the combination of the target and the superimposed light structure, e.g. moiré fringes, and carries information about target detail which simple, unstructured illumination does not. The “superresolved” components, however, need disentangling to be revealed.

Multiple parameter use within traditional diffraction limit: if a target has no special polarization or wavelength properties, two polarization states or non-overlapping wavelength regions can be used to encode target details, one in a spatial-frequency band inside the cut-off limit the other beyond it. Both would utilize normal passband transmission but are then separately decoded to reconstitute target structure with extended resolution.

Probing near-field electro-magnetic disturbance. The usual discussion of superresolution involved conventional imagery of an object by an optical system. But modern technology allows probing the electromagnetic disturbance within molecular distances of the source[4] which has superior resolution properties, see also evanescent waves and the development of the new Super lens.a

Geometrical or image-processing superresolution

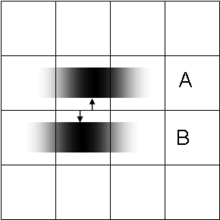

Multi-exposure image noise reduction. When an image is degraded by noise, there can be more detail in the average of many exposures, even within the diffraction limit. See example on the right.

Single-frame deblurring. Known defects in a given imaging situation, such as defocus or aberrations, can sometimes be mitigated in whole or in part by suitable spatial-frequency filtering of even a single image. Such procedures all stay within the diffraction-mandated passband, and do not extend it.

Sub-pixel Image Localization. The location of a single source can be determined by computing the "center of gravity" (centroid) of the light distribution extending over several adjacent pixels (see figure on the left). Provided that there is enough light, this can be achieved with arbitrary precision, very much better than pixel width of the detecting apparatus and the resolution limit for the decision of whether the source is single or double. This technique, which requires the presupposition that all the light comes from a single source, is at the basis of what has becomes known as superresolution microscopy, e.g. STORM, where fluorescent probes attached to molecules give nanoscale distance information. It is also the mechanism underlying visual hyperacuity.[8]

.

Bayesian Induction from within to beyond traditional diffraction limit. Some object features, though beyond the diffraction limit, may be known to be associated with other object features that are within the limits and hence contained in the image. Then conclusions can be drawn, using statistical methods, from the available image data about the presence of the full object.[9] The classical example is Toraldo di Francia's proposition[10] of judging whether an image is that of a single or double star by determining whether its width exceeds the spread from a single star. This can be achieved at separations well below the classical resolution bounds, and requires the prior limitation to the choice "single or double?"

The approach can take the form of extrapolating the image in the frequency domain, by assuming that the object is an analytic function, and that we can exactly know the function values in some interval. This method is severely limited by the ever-present noise in digital imaging systems, but it can work for radar, astronomy, microscopy or magnetic resonance imaging.[11]

Aliasing

Geometrical SR reconstruction algorithms are possible if and only if the input low resolution images have been under-sampled and therefore contain aliasing. Because of this aliasing, the high-frequency content of the desired reconstruction image is embedded in the low-frequency content of each of the observed images. Given a sufficient number of observation images, and if the set of observations vary in their phase (i.e. if the images of the scene are shifted by a sub-pixel amount), then the phase information can be used to separate the aliased high-frequency content from the true low-frequency content, and the full-resolution image can be accurately reconstructed.[12]

In practice, this frequency-based approach is not used for reconstruction, but even in the case of spatial approaches (e.g. shift-add fusion[13]), the presence of aliasing is still a necessary condition for SR reconstruction.

Technical Implementations of SR

There are both single-frame and multiple-frame variants of SR. Multiple-frame SR uses the sub-pixel shifts between multiple low resolution images of the same scene. It creates an improved resolution image fusing information from all low resolution images, and the created higher resolution images are better descriptions of the scene. Single-frame SR methods attempt to magnify the image without introducing blur. These methods use other parts of the low resolution images, or other unrelated images, to guess what the high-resolution image should look like. Algorithms can also be divided by their domain: frequency or space domain. Originally, super-resolution methods worked well only on grayscale images, [14] but researchers have found methods to adapt them to color camera images.[13] Recently, the use of super-resolution for 3D data has also been shown.[15]

See also

- Diffraction-limited system

- Super resolution microscopy

- Optical resolution

- Aliasing

- Oversampling

- Compressed sensing

External links

- Infognition

- PhotoAcute

- Hasselblad H4D-200MS performs in-camera sensor-shift superresolution.

- Nero AG

References

- ↑ Born M, Wolf E, Principles of Optics, Cambridge Univ. Press , any edition

- ↑ Fox M, 2007 Quantum Optics Oxford

- ↑ Zalevsky Z, Mendlovic D. 2003 Optical Superresolution Springer

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Betzig E, Trautman JK., 1992. Near-field optics: microscopy, spectroscopy, and surface modification beyond the diffraction limit. Science 257, 189–195.

- ↑ Lukosz, W., 1966. Optical systems with resolving power exceeding the classical limit. J. opt. soc. Am. 56, 1463–1472.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Gustaffsson, M., 2000. Surpassing the lateral resolution limit by a factor of two using structured illumination microscopy. J. Microscopy 198, 82–87.

- ↑ Cox, I.J., Sheppard, C.J.R., 1986. Information capacity and resolution in an optical system. J.opt. Soc. Am. A 3, 1152–1158

- ↑ Westheimer, G. 2012 Optical superresolution and visual hyperacuity. Prog Retin Eye Res. 31(5):467-80.

- ↑ Harris, J.L., 1964. Resolving power and decision making. J. opt. soc. Am. 54, 606–611.

- ↑ Toraldo di Francia, G., 1955. Resolving power and information. J. opt. soc. Am. 45, 497–501.

- ↑ D. Poot, B. Jeurissen, Y. Bastiaensen, J. Veraart, W. Van Hecke, P. M. Parizel, and J. Sijbers, "Super-Resolution for Multislice Diffusion Tensor Imaging", Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, (2012)

- ↑ J. Simpkins, R.L. Stevenson, "An Introduction to Super-Resolution Imaging." Mathematical Optics: Classical, Quantum, and Computational Methods, Ed. V. Lakshminarayanan, M. Calvo, and T. Alieva. CRC Press, 2012. 539-564.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 S. Farsiu, D. Robinson, M. Elad, and P. Milanfar, "Fast and Robust Multi-frame Super-resolution", IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, vol. 13, no. 10, pp. 1327–1344, October 2004.

- ↑ P. Cheeseman, B. Kanefsky, R. Kraft, and J. Stutz, 1994

- ↑ S. Schuon, C. Theobalt, J. Davis, and S. Thrun, "LidarBoost: Depth Superresolution for ToF 3D Shape Scanning", In Proceedings of IEEE CVPR 2009

Other related work

- Craig H. Curtis, Tom D. Milster (1992), "Analysis of Superresolution in Magneto-Optic Data Storage Devices," APPLIED OPTICS, October 1992, Vol. 31, No. 29, pp. 6272–6279.

- Z. Zalevsky and D. Mendlovic (2003), Optical Superresolution, Springer. ISBN 0-387-00591-9

- J.N. Caron, "Rapid supersampling of multiframe sequences by use of blind deconvolution," Optics Letters, September, 2004, Vol 29, No. 17, p. 1986–1988.

- G.T. Clement, J. Huttunen, and K. Hynynen, "Superresolution ultrasound imaging using back-projected reconstruction" Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Volume 118, Issue 6, pp. 3953–3960, 2005.

- V. Cheung, B. J. Frey, and N. Jojic. "Video epitomes". In Proc. IEEE Conf. on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2005.

- M. Bertero and P. Boccacci. "Super-resolution in computational imaging". Micron, 34:265–273, October 2003.

- S. Borman and R. Stevenson. Spatial Resolution Enhancement of Low-Resolution Image Sequences – A Comprehensive Review with Directions for Future Research", Technical report, University of Notre Dame, 1998.

- S. Borman and R. Stevenson. "Super-resolution from image sequences — a review" in Proc. Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems, 1998.

- S. C. Park, M. K. Park, and M. G. Kang., "Super-resolution image reconstruction: a technical overview", IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 20(3):21–36, May 2003.

- S. Farsiu, D. Robinson, M. Elad, and P. Milanfar. "Advances and Challenges in Super-Resolution", International Journal of Imaging Systems and Technology, Volume 14, no 2, pp. 47–57, August 2004

- M. Elad and Y. Hel-Or, "Fast Super-Resolution Reconstruction Algorithm for Pure Translational Motion and Common Space-Invariant Blur ", IEEE Trans. on Image Processing, Vol 10, No 8, pp. 1187–1193, August 2001.

- M. Irani and S. Peleg, "Super Resolution From Image Sequences", ICPR, 2:115—120, June 1990.

- F. Sroubek, G. Cristobal, and J. Flusser, "A Unified Approach to Superresolution and Multichannel Blind Deconvolution", IEEE Trans. Image Processing, vol. 16, pp. 2322–2332, 2007

- A. Calabuig, V. Mico, J. Garcia, Z. Zalevsky, and C. Ferreira, “Single-exposure super-resolved interferometric microscopy by RGB-multiplexing,” Opt. Lett. 36, 885–887 (2011)

- W.-S. Chan, E. Lam, M. Ng, and G. Mak, "Super-resolution reconstruction in a computational compound-eye imaging system,” Multidimensional Systems and Signal Processing, 18(2–3), pp. 83–101, 2007.

- M. Ng, H. Shen, E. Lam, and L. Zhang, “A total variation regularization based super-resolution reconstruction algorithm for digital video,” EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing, ID 74585, 2007.

- D. Glasner, S. Bagon, and M. Irani, "Super-Resolution from a Single Image", International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), October 2009. example and results

- M. Ben-Ezra, Z. Lin, B. Wilburn, and W. Zhang, "Penrose Pixels for Super-Resolution," IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (PAMI),

Vol.33, No.7, pp. 1370-1383, July 2011 "Penrose pixels for super-resolution",