Sulphur Bank Mine

| |

| Location | |

|---|---|

Sulphur Bank Mine Location in California

| |

| Location | Clearlake Oaks, Lake County |

| California | |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 39°00′14″N 122°39′59″W / 39.00389°N 122.66639°WCoordinates: 39°00′14″N 122°39′59″W / 39.00389°N 122.66639°W |

| Production | |

| Products | Borax, Sulfur, Mercury |

| History | |

| Opened |

1856 (California Borax Co) 1875 (Sulphur Bank Quicksilver Mining Co) 1927 (Bradley Mining Co) |

| Closed |

1957 |

| Reference No. | 428 |

| Owner | |

| Company | Bradley Mining Company |

| Year of acquisition | 1927 |

The Sulphur Bank Mine is located near Clearlake Oaks and Clear Lake in Lake County, California. The 150-acre (0.61 km2) mine became one of the most noted mercury producers in the world.[1]

During the 150 years since the Sulphur Bank was discovered, the area has drawn geologists, inspired unique scientific theories, established constitutional case law and now attracts environmental scientists who study the impact of mercury contamination within the Cache Creek watershed of northern California and the Sacramento River-Delta Region and San Francisco Bay.

History

Beginning in 1856, the mine was first worked for borax. Mining for sulfur began in 1865, and produced 2,000,000 pounds (909,090 kg) in four years. Mercury ore was mined intermittently by underground and open-pit methods from 1873 to 1957. Sulphur Bank Mine was credited with a total output of 92,400 flasks (7.02 million pounds) by 1918. The mine was an important producer during both world wars.[1]

The mine closed in 1957 and is a California Historical Landmark (#428).[2] Sulphur Bank Mine became an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) superfund site in 1990.[1]

California Borax Co

Although the hot springs of the Sulphur Bank contained borax, the search led John Allen Veatch to nearby Borax Lake where the California Borax Company established the first commercial borax mining operation in the U. S. beginning in 1860 and ceasing in 1868. The company established land claims to Borax Lake, the Sulphur Bank and Sulphur Springs in Colusa County.[3]

The officers of the California Borax Company included physicians Veatch, William Ayers and Robert Oxland; and lawyers Henry Halleck, Archibald Peachy, William Billings and Solomon Heydenfeldt.[4] The fascination with borax resulted from the fact that boric acid was critical as a flux in metal working. All borax at that time was imported, mostly from the Tuscan Lakes area of Italy. The California Borax Company did engage in sulfur mining at Sulphur Bank (extracting 2 million pounds in 4 years)[5] for a time before the company’s collapse in 1868 and the sulfur was discovered to be contaminated with cinnabar.[6]

Discovery of cinnabar

Between the time of Veatch’s discovery and the working of sulfur, a minor mining excitement led to the discovery of cinnabar in the northern reaches of Napa County (of which Lake County was then a part). The Silverado rush in the winter of 1858–59 caused “every unemployed man from Soscol to Calistoga turned prospector. Blankets and bacon, beans and hard bread rose to a premium,” reported William T. Montgomery in a light-hearted sketch of the great silver rush that resulted in enormous finds of worthless iron pyrites.[7] But the rush did result in the discovery of cinnabar in 1860. Montgomery, who became a stockholder in the X.L.C.R.[8] (pronounced excelsior) mine, is the only known source of the often-repeated tale of Seth Dunham and L.D. Jones discovering cinnabar in a road cut of the Barryessa-Lower Lake Road (now Morgan Valley Road)[8] in what became known as the Knoxville mining district, about a dozen miles south east of the Sulphur Bank in present-day Napa County. The X.L.C.R. became known as the Redington mine a decade later and was second only to the New Almaden mine in production.[8]

Another account of the discovery of cinnabar in the same region is contained in the December 1861 edition of Scientific American magazine. “There has been recently opened an extensive cinnabar vein, in Napa County, which promises to be rich. This was discovered by John Newman, of Pope’s Valley. The cinnabar was discovered by means of the fires which are made to burn off the chaparral,” the magazine reported.[9]

Newman became a stockholder of the Phoenix mine in that location.[10] These early discoveries of mercury-bearing ores did not become viable mercury producers until 1872, when the price of mercury and improved smelting methods resulted in the establishment of many mines in Lake and Napa counties.

John and Tiburcio Parrott

In 1873,[11] the defunct California Borax Company was acquired by Tiburcio and John Parrott, William F. Babcock and Darius Ogden Mills, for the purpose of quicksilver mining at Sulphur Bank.[12] Until 1875, when the mine shipped 5,218 flasks of mercury, it operated under the name of the borax company but then changed the name to the Sulphur Bank Quicksilver Mining Company.[13]

Tiburcio Parrott was controlling partner of the new company, and it was he who was later jailed when the company refused to abide by a state law excluding Chinese from employment.[11]

Tiburcio’s father, John Parrott, was a wealthy banker. Parrot and Company, of San Francisco was a major landholder and banking firm. John Parrot’s weekend retreat consisted of 17,000 acres (69 km2) in San Mateo County, California. John Parrot also owned 8% of the giant New Almaden quicksilver mine in Santa Clara County.[14]

Babcock was an officer of Parrott and Company and was a partner with Tiburcio Parrott in an import-export company. Mills was also asset rich, founding the Bank of California, but who had stepped down as bank president by the time of the Sulphur Bank mercury mining era. It was Mills who later saved Bank of California with his personal assets when it failed under William Chapman Ralston.[12]

The period of 1875 to 1883 was the heyday of the mining activity. The Sulphur Bank Quicksilver Mine often had the highest output after the New Almaden, the New Idria (San Benito County) and the Redington. However, profits were tempered by the temperature of the underground workings. The Chinese miners, who did most of the underground work, had to endure temperatures of 176 °F (80 °C) because the ore body followed the path of at least three hot springs at the site.[15]

The mercury was shipped in iron flasks weighing about 90 pounds each and containing 76.5 pounds of mercury.[16] The closest rail service was 45 miles (72 km) away in Calistoga. The wagon trip over the crest of Mt Saint Helena via the Lawley Toll Road to the rail head could take a week or more.[17]

Just how much mercury was shipped from Sulphur Bank is a matter of some estimation. The History of Lake County 1881 puts production at 12,341 flasks in the two-years 1874-1876.[13] Walter W. Bradley, state mineralogist, estimated total output to 1918 at 92,400 flasks. The mine was only sporadically worked after 1883, so the majority of the output can be attributed to the Parrott era.[5]

Eastlake township

The township of Eastlake was established next to the mine. The mining superintendent, Ferdinand Fiedler listed his address at Eastlake as did assistant superintendent, J.E. Tucker. The German-born Fiedler was the furnace operator and postmaster at the New Almaden mine before taking the post of superintendent at Sulphur Bank. The mine’s owner-investors all lived in San Francisco. Eastlake was directly adjacent to the mining property. After the mine closed, Eastlake was abandoned.[18]

Those who worked at the mine in 1880 constituted an ethnic soup of foreign-born workers. The 1880 federal census, dated June 22, 1880, listed 218 Chinese-born men and 40 Occidentals associated with the mine. Only a few of the white miners were born in the United States. Immigrants from Sweden and Norway constituted the bulk of the European miners. A few of the miners were Irish born as were two Mexicans. Most of the miners had no families present but some of the managers had families and children living at Eastlake. None of the Chinese miners had families present.[19]

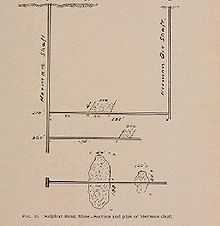

Mine workings

The quicksilver mine was partially an open pit and partially a tunneling operation. Three shafts and a series of lateral tunnels known as drifts comprised the underground works. The shafts were known as the Hermann, the Fiedler and the Parrott.[15] From historical documents it appears only the Wagon-Spring Cut and Bath-house Cut (open pits) and the Parrott shaft were used for mining until 1880. By 1881 the other two shafts were also in place, one of which reached 260 feet (79 m).[20] Bath-House and Parrott flooded then and were not further used.[21]

"At Sulphur Bank tunnels were used in developing and mining the ore just under and in the basalt capping. In depth, development and mining proceeded through shallow shafts. Operations from any one shaft were carried on until the hot water and gas made conditions intolerable, when the shaft was abandoned and a new one was sunk a short distance away." Curt Schuette, the author of the US Bureau of Mines bulletin #335 observed.[22]

The cinnabar ore, known also as mercury sulfide (84 parts mercury to 16 parts sulfur), was treated in furnaces and retorts near the mine. The essential refining method was to turn the mercury into gas and recondense it to quicksilver. The sulfur would burn and convert to carbon; the waste rock associated with the ore is known as calcine, or burnt rock, would be dumped near the lake shore, out of the way of the mining works. All of the furnaces at all of the mines in the vicinity were wood fired.[16]

End of the Parrott era

The heyday of quicksilver mining came to an end when the price of quicksilver dropped to $25 per flask from a high in 1874 of $120.[23] The Sulphur Bank Quicksilver Mining Company was bankrupt by 1883. Tiburcio Parrot’s biographer states the company’s stock went into default, which suggests the stock was pledged against loans to cover operating expenses. Who the creditors were or to whom the mine was sold is unknown. A specialized census report indicates 2,283 flasks were produced there in 1890,[24] which was a fraction of the output reported during the census of 1880 (10,706 flasks).

The township of Eastlake, which included a dry goods store, post office and a hotel-restaurant was abandoned after the mine’s closure.

The mine was apparently inactive through the remainder of the 1880s. Geologist George F. Becker visited the mine several times between 1883 and 1888. Becker’s survey of quicksilver mining in the western United States usually includes the names of watchmen or mine personnel at the sites he studied, but no names are mentioned during his visits to Sulphur Bank. The Fiedler shaft was flooded and overflowing into Clear Lake in 1887. The mine was operated sporadically in the 1890s, evidenced by the presence of mine superintendent Richard White.

John Parrott died in 1884, and his widow, Abigail inherited control of Parrott and Company. Abigail was not the mother of Tiburcio Parrott. He was born 1842, the bastard child of John Parrott and Deloris Ochoa.[25] John Parrott was the American Consul to Mexico at Mazatlan. The War with Mexico in 1845-1846 put a temporary end to the diplomacy business. John Parrott then set up his banking and real estate business in San Francisco in 1848 or 1850.[26]

Tiburcio Parrott was educated in the United States and Europe. After the failure of the mercury mine, he spent the last decade of his life founding and operating a wine estate, near the township of St. Helena, California.[27] There he became closely associated with the German-born Beringer Brothers: Frederick and Jacob. Tiburcio Parrott died in 1894.[28]

In 1901, the Sulphur Bank mine was sold to a group of New York bankers.[29]

Empire Consolidated

By 1902, Sulphur Bank mine was operating as the Empire Consolidated Quicksilver Company and a new shaft, the Empire, was sunk. Riley A. Bogges was listed as owner/ general manager. “It is greatly to be regretted that the management of this property has not taken pains to preserve geological descriptions of the underground works, which are all caved in, except the Empire shaft, now in progress of sinking. The latter is so tightly timbered, owing to bad ground, that it offers no opportunity’ to study the formations through which it has passed,” wrote William Forstner, of California State Mining Bureau. He also observed that Sulphur Bank had the appearance of an abandoned hydraulic mine.[30]

Riley Boggess

Boggess, often spelled as Bogges, (the 1900 census gives the spelling as Boggess [31]) got the mine mired in court battles in the state of New York, where he also lined up his investors. “Riley A. Boggess had been connected with the mine, and in 1901 he promoted the formation of the Empire Consolidated Quicksilver Mining Company, floated a considerable amount of stock in the East and secured the names of prominent New York capitalists for directors. The new company purchased the Sulphur Banks and the Abbott mines in Lake county, and the Central and Empire mines in Colusa county. The mines were never opened, and the stockholders’ money was wasted. The record of the Sulphur Banks since has been constant litigation and abandoned works, but it is believed by many that rich ore still exists there,” as the history of Mendocino and Lake Counties summarized events.[32]

The summary appears reasonably accurate based on New York Times reports: “A big deal in California quicksilver mines was made today when New York capitalists bought for $1,000,000 the Sulphur Bank and Abbot mines in Lake County and Empire and Central, in Colusa County, which are among the largest producers in the world. From the first two mines $2,000,000 in quicksilver has been taken but the Colusa mines are only partly developed,” the paper reported on October 11, 1901. The article lists the buyers as bankers William Dowe, William Kimball, William Scherer, and iron monger Henry Adams as director.[29]

Deal collapses

The deal began to unravel a year later. The broker of the first deal, John T. Reed, won a suit against Boggess, the Times reported July 25, 1902, and in the July 6 edition, the paper noted a lawsuit filed by Katrryn Plumer, of Brooklyn alleging Boggess, Reed, and others had defrauded her of her 1897 investment in the mines.[33] In addition, a July 17, 1902 article related a series of complex stock manipulations involving the Empire Consolidated Quicksilver Mining Company.[34]

There is no evidence how Plumer’s claim was resolved, but the millions of dollars allegedly on or under the table boiled down to $750 in cash by 1903. “United State Marshal Henkel sold by auction yesterday 379,985 shares of the stock of the Empire Consolidated Quicksilver Mining Company, which was bid in for $750 by William Hughes of 100 Nassau Street. The stock was seized ... to satisfy a judgement ... against Riley A. Boggess. The stock had been pledged with the North American Trust Company to secure loans. ... ” The Times reported April 21, 1903.[35]

George Ruddock

The Sulphur Bank mercury mine next became the possession of George T. Ruddock, a mining engineer and amateur botanist,[36] who lived in Alameda in 1910 and San Francisco by 1920. How he came into possession of the property and surrounding acreage is unclear. Walter W. Bradley’s report on quicksilver mining in California lists Ruddock as the owner of Sulphur Bank by 1918 and that Ruddock had the mine under lease to an H.W. Gould.[5]

State mineralogist W.W. Bradley indicated Sulphur Bank had not been worked or de-watered since 1906. The old Empire Consolidated Quicksilver Mining Company was now headed by Riley Boggess’ wife, Emma, which still held possession of the Abbott and other mines near Sulphur Creek in Colusa and Lake counties. Neither the Abbott nor Sulphur Bank were being actively worked.[5] “For the present at least, no underground work is planned, there being several hundred thousand tons at the surface, estimated as material available for treatment ... Practically all of the dumps in sight and some over the hill on the north side, have concentratable values in cinnabar. The material can be cheaply excavated with a steam shovel and transported to the mill by motor trucks, as it will have to be moved distances up to mile and raised to the top of the mill bin,” Bradley reported.[5]

Whether the plan for mining exclusively by open-pit methods proceeded is uncertain but that method was employed a decade later when the Bradley Mining Company acquired the Sulphur Bank mercury mine.

Bradley Mining Company

Frederick Worthen Bradley, the head and founder of the family-owned Bradley Mining Company, became both famous and infamous in 19th Century American history, unknowingly surviving two assassination attempts and setting records for low-cost ore production. His history is well documented on both the internet and print. [37][38][39]

There is no known connection between Bradley Mining Company and Walter Wadsworth Bradley, who would become the California State Mineralogist.

Frederick's father, Henry Sewall Bradley came to California to work the gold fields, became a land surveyor instead, and died in 1881 when Frederick Bradley was mid-way through his education at the University of California.[40]

Frederick Bradley dropped out of school, borrowed $5,000 and took over ownership/management of the existing Spanish mine on the south fork of the Yuba River, setting a record for low-cost ore production. He was inducted into the Mining Hall of Fame in 1988.[41]

By 1893, Frederick Bradley assumed management (but not ownership) of the Bunker Hill lead mine, near Coeur d' Alene, Idaho. Between 1894 and 1904 Bradley made the money-losing low-grade ore profitable but at the cost of a civil war between the mining company and the Western Federation of Miners union. Testimony at the 1906 murder trial of Big Bill Haywood, the union treasurer disclosed the two assassination attempts against Bradley in San Francisco in 1904.[42] Bradley then went off to Alaska to turn two money-losing gold operations into profitable ventures.[41] Mt. Bradley in Alaska is named for him.[43]

Bradley Mining Company first optioned Sulphur Bank mercury mine from Ruddock in 1927 and then purchased the mine and surrounding 700 acres (2.8 km2). The mine was operated under the name, Sulphur Bank Syndicate, but eventually operated as the Bradley Mining Company. Worthen Bradley, Frederick’s son, became assistant superintendent of the mine soon after he was graduated at the University of California, Berkeley in 1926. He eventually served as president of the Bradley Mining Company.[44]

In later years, Worthen Bradley recalled the Bradleys’ interest in the Sulphur Bank mine was generated by a rise in the price of quicksilver. During the Depression years of the 1930s the mine was active or inactive, dependent upon the price, he told a local newspaper in 1955.[44] “We are trying to do with one shovel and two shifts, what we did with several in World War II," Bradley said in 1955. “We are still in the stage of getting started and hope to begin plant operation this month, September. Unfortunately the quicksilver market has declined somewhat since we began work,” The Sulphur Bank mercury mine closed permanently in 1957.[44]

Rancho Solfatara

Frederick Worthen Bradley, the founder of the company, died in 1933. The son, Worthen then took over operation of the mine and developed a summer estate known as Rancho Solfatara on 800 acres (the mine included 700 acres (2.8 km2); another 100 acres (0.40 km2) was added in the 1950s) adjoining the mine. Rancho Solfatara, was used first for stock raising to feed the 100 miners who lived there during World War II. During the war, the demand for quicksilver skyrocketed because of its use in detonators in munitions.[44]

Worthen Bradley died at age 55, in 1959. Helen Pope Bradley, who wed Worthen in 1929, engaged in raising show stock, known as Polled Herefords in 1943. Helen lived until 2006, a month before her 100th birthday.[44]

Worthen Bradley was born Frederick Worthen Bradley but used Worthen as his first name. A son, Frederick Worthen Bradley, an attorney, is now the president of the Bradley Mining Company. The Sulphur Bank Mine and Rancho Solfatara are held by the company and the Worthen Bradley Trust.

Present day

The mine currently consists of mine tailings, waste rock and a flooded open pit mine (known as the Herman Impoundment or Herman Pit). Approximately two million cubic yards of mine wastes and tailings remain on the site. The Herman pit, which is filled with acidic water, covers 23 acres (93,000 m2) to a depth of 90 feet (27 m) and is located 750 feet (230 m) upslope of Clear Lake. The Elem Tribal Colony of Pomo Indians is located directly adjacent to the mine property. A freshwater wetland is located to the north of the mine, and critical habitat for three endangered species of wildlife, the Peregrine Falcon, Southern Bald Eagle, and Yellow-billed Cuckoo, is less than a quarter-mile from the site.[1]

The mine site has been implicated by the EPA in mercury pollution of Clear Lake, but the allegations are disputed by Bradley Mining Company, the last and current owner of the mine.[45]

The EPA years

The discovery of mercury in the fish of Clear Lake was accidental. The California Department of Fish and Game's biologist, Larry Week was testing fish samples in 1976 for DDD, a close relative of DDT the pesticide, and discovered high levels of mercury in fish tissue.[46] During the next decade, various state and federal agencies conducted tests of the lake and mine site resulting in the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) placing Sulphur Bank Mercury Mine in 1990 on the National Priorities List (NPL) under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act or CERCLA.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry was also established by CERCLA under the federal Department of Health and Human Services. The Registry assesses the health hazards and risks at contaminated sites and makes recommendations reducing those hazards. The mine site has been proposed for listing on the NPL since 1988 and the Registry published its report the next year, concluding Sulphur Bank Mine is a public health hazard.[47] (See also Mercury poisoning.)

In 1990, the EPA began studies on the flooded pit, waste rock piles, lake sediments and a nearby wetland.

The EPA completed an emergency remediation in 1992, where the slope of mine tailings was cut back along the shoreline, covered with clean soil and reseeded.[48] The agency states that more than 32 acres (130,000 m2) of waste rock had been deposited into the lake, and piled up along the shore.[49] The book History of Lake County 1881 gives more detail: "The debris is drawn from the bottom of the furnance about every two hours and is wheeled to the far-distant dump on the lake shore."[16]

Other EPA cleanup actions included an earthen dam built between the flooded acidic open pit (called the Herman Impoundment after one of the mining shafts named Herman) and the shoreline in 1996, a 4,000-foot (1,200 m) pipeline to divert surface water runoff away from the pit in 1999, and contaminated soil removal from the adjacent Elem Indian Colony in 1997.[48]

Bradley Mining Company legal action

In 1992, the Bradley Mining Co. petitioned the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals for a review of the EPA's rulemaking listing the mine site on the National Priorities List, asserting that the agency, "acted arbitrarily and capriciously in listing the property because the EPA failed to demonstrate that mercury found in an adjacent lake was caused by mining operations and because the Agency incorrectly calculated the risk that the mercury would contaminate usable ground water."[45]

The EPA presented a study from 1990 titled Abatement and Control Study: Sulphur Bank Mine and Clear Lake, to support the rulemaking. The EPA asserted that its listing decision was based upon: That mercury levels were much higher closest to the mine site in lake sediment, that the groundwater was at risk for contamination and that soil erosion along the shoreline into the lake is occurring.

The court ruled in favor of the EPA and denied the Bradley petition stating, " Thus, the record provides a sufficient foundation for the EPA's conclusion that an observed release of mercury occurred." The court also added "Given the highly technical issues involved in the Agency's decision to list a facility, this court gives significant deference to the EPA's determination. The judges cited from a ruling in Wisconsin challenging an EPA listing: "[T]he importance of EPA's goals, including protecting human life from potentially disastrous contamination and the congressionally mandated need for speedy action," so that "[i]t is not necessary that EPA's decisions as to what sites are included on the NPL be perfect, nor even that they be the best."[50]

UC Davis studies

The tests of lake sediments and water for mercury from 1992 through 1998 show increasingly higher levels of mercury from samples taken closest to the mine site.[51] How the mercury is getting into the lake and its food chain is still unclear.[52] The UC Davis researchers' theory is that acid mine drainage is seeping through the contaminated waste rock and then entering the lake from underground in addition to surface runoff, leaching mercury into the lake.[52] The source of the acidity may be the flooded Herman pit which has a tested pH level of 3.2.[53]

This underground system is difficult to study as, "the miners ripped the relatively compact natural sulfide deposit to pieces, jumbled uneconomic minerals together with miscellaneous overburden rock, and piled the resulting poisonous mélange 30 or 40 feet deep over the tunnel-laced rock of the former underground mine. Finding out how water and air flow through the resulting mess is a very difficult task." [54]

This difficulty is shown by tracer experiments conducted by UC Davis in 1997 and 1998 to find the subsurface water flow from the Herman Pit to the lake. The tracers used were Rhodamine-WT, sulfur hexafluoride, and a mixture of sulfur hexafluoride and neon-22.

Herman pit in foreground, Mt Konocti in background, Clear Lake in center.

"The three sets of experimental results presented all support a through-flow rate in Herman Pit. Even though it is known that water from Herman Pit is flowing into Clear Lake, it cannot be estimated [emphasis added] from these calculations how much is going into the lake or the precise path the flow is taking" the study noted. "Of the approximate 630 liters per second flowing into and out of Herman Pit, fluid may leave the pit and flow directly into the lake through the waste rock piles, through the native sediment that underlies the waste rock piles, or simply flow elsewhere." wrote S. Geoffrey Schlado, Jordan F. Clark, in the study, Use of Tracers To Quantify Subsurface Flow Through A Mining Pit. [55]

Another theory is of geothermal springs being the source for inorganic mercury in Clear Lake, as there are abundant springs emanating from the lake bed.[56] Deep core samples of sediments taken in the 1980s show peaks of mercury during prehistoric times that "likely originated from natural processes such as volcanic and/or tectonic activity within the Clear Lake Basin" [56] A report published in Geology, November 1987 theorized, "that mercury-rich geothermal fluids rose along the activated fractures and faults and were discharged into the lake, causing the anomalously high Hg[Mercury] content of the sediments and leading to deposition of the Sulphur Bank Hg deposit. The total amount of Hg discharged into Clear Lake over the past 15,000 years is estimated to be at least 2,400 metric tons."[57][58][59]

The EPA-funded research by UC Davis found that total levels of mercury (TotHg) in the lake sediments has "not declined significantly a decade after" the remediation work in 1992 at Sulphur Bank Mine.[60]

Cleanup plans and costs

In 2005, the EPA placed a lien on 554 acres (2.24 km2) of Bradley-owned property at the mine site to recover cleanup costs estimated at $27 million. Cost estimates for future cleanup go as high as $40 million.[61] Another $1.7 million was agreed upon in a settlement between the EPA and NEC Acquisition Company, the parent company of Earth Energy,Inc., for the costs of re-closing three geothermal wells at Sulphur Bank.[62] The wells were drilled in the 1960s to explore the possibility of geothermal energy production, but of the three test wells at Sulphur Bank, only one was productive and the project was abandoned in the 1980s.

Rick Sugarek, project manager for the Superfund site told the Lake County News in 2009 that the EPA has been working with the state on a cleanup plan, but a main sticking point has been the need to run a treatment plant to deal with the water in the Herman Pit. "We need to stop that flow, and that's why we need the treatment plant. " The question then is where should the water from the pit be discharged? There is no good answer to that, he said. "One of the options was piping the water to The Geysers for injection." Sugarek added, " there are legal and technical problems with that plan." The total cost estimates to build a treatment plant and remove all of the mine waste could run between $30 million and $40 million.[63] The Geysers are already receiving treated wastewater from both Lake County and Santa Rosa, in Sonoma County.

A review paper dated Fall 2008 on the Sulphur Bank Mine site remediation, authored by J. Lessl, University of Florida, Department of Soil and Water Sciences suggests phytoremediation, which is the use of both wild and genetically-modified plants to take up (hyper-accumulate) and bank the mercury and arsenic in the plant tissue. The plants have been genetically altered for this specific purpose. The report also suggests the less expensive option of adding soil amendments like compost, lime and fertilizer. "This technology relies on the intrinsic ability of organic matter to bind metals, reducing their bioavailability and subsequently allowing vegetation to become established" which would ideally, "impede the spread of water erosion and reduce water ingress and subsequent metal leaching."[64] The suggestions in the review paper are based on several studies, two of which are; Remediation of metal polluted mine soil with compost: Co-composting versus incorporation by Susan Tandy, 2008, and Phytoremediation of toxic elemental and organic pollutants by Richard B. Meager, 2000.[64]

2009 Recovery Act

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was passed by the US Congress in February 2009 and provides $600 million for hazardous waste cleanup, with $5 million of that going to Sulphur Bank Mine and access road work. The funds will pay for the remediation on BIA 120, the road to the Elem Indian Colony adjacent to the mercury mine property.[65] The Bureau of Indian Affairs built BIA 120 using Sulphur Bank mine tailings in the 1970s.[63]

The mine tailings and waste rock, in addition to being used for road and house construction in the Elem Indian Colony, was also used by the company Aggrelite in the 1950s. The company operated a concrete block plant at Sulphur Bank Mine and used the tailings to produce 27 different bricks of varying colors and size. The state Division of Mines report of 1953 described the operation, "Mine dump material, ... is crushed and screened to minus one-half inch and mixed with one-third part of furnace calcines from the dump below the quicksilver plant ... Plant capacity is 2000 bricks per 8-hour shift. The finished product is used locally and trucked to the San Francisco Bay area." [66]

People

Between its rise as a geological wonder and its fall from grace as an EPA superfund site, the Sulphur Bank Mercury Mine was able to attract admirers that reads like a Who’s Who of California History.

John Veatch

The first was John Allen Veatch, physician, land surveyor and mineralogist who gave the Sulphur Bank its name in 1856, while on a quest for a domestic supply of borax. Veatch had arrived in California at the time of the 1849 California Gold Rush, became a corresponding member of the California Academy of Sciences and established the first borax mine in the United States.[3]

“In due time, I again reached the “white hill,” Veatch wrote in a letter that now serves as a history of discovering the Sulphur Bank and Borax Lake. "I now discovered, for the first time, that the “white hill” was mostly a mass of sulphur fused by volcanic heat. The external crust, composed of sulphur mixed with sand and earthy impurities, formed a concrete covering of a whitish appearance, hiding the true nature of the mass beneath." [3]

“On breaking the crust, numerous fissures and small cavities lined with sulphur crystals of great beauty were brought to light. Through the fissures, which seemed to communicate with the depth below, hot aqueous vapors and sulphurous fumes constantly escaped," Veatch wrote in his letter to the California Borax Company, dated 1857.[3]

Chinese mine workers

The 1880 Census indicates more than 218 Chinese mine workers at Sulphur Bank Mine. The use of Chinese labor in the underground workings was pervasive in the mines of California.[37]

Hostility towards the Chinese was also pervasive. Workingmen in California viewed the Chinese as unfair competition. The mine owners could hire four Chinese workers for the price of one white miner. The going price in that era was typically $4 per day for a white miner versus $1 per day for a Chinese man.[67]

Local legend [68] suggests that some Chinese miners were killed at the Sulphur Bank mine when hot springs flooded the mining chambers, scalding the workers. At least one cave-in did occur in October 1881, A New York Times report [69] of the incident alludes to loss of life, but those who died in the accident were not Chinese; The five miners were all of Cornwall, England.[18]

The issue came to a head on Feb 13 1880. The California Legislature amended the state constitution, adding sections forbidding the Chinese from working for wages. The law also threatened the corporate charter of any industry that did not comply.[68] Most of the mine owners discharged their Chinese workers, but Sulphur Bank Quicksilver Mining Company did not. Tiburcio Parrott was arrested Feb. 22 after he gave notice to the California Attorney General A.L. Hart that the company would not comply. He asserted that "he would not be dictated to by any man, or set of men, excepting due process of law."[70] Tiburcio Parrott then sued California in the federal Ninth Circuit District court seeking a writ of habeas corpus: California had unconstitutionally deprived him of his liberty. Parrot won. In a decision issued March 22, 1880, the court ruled California could only revoke a corporate charter for threatening public health or morals. Additionally the court ruled only the federal government could sign or revoke an international treaty. The Burlingame Treaty of 1868 was then in force and assured unlimited immigration of Chinese to America and Americans to China. This treaty included the right to work, the court ruled.[70][71]

Tiburcio Parrott gained his freedom and the Sulphur Bank miners maintained their employment. The situation was more enigmatic at the Great Western mercury mine south of Middletown, also in Lake County. Hundreds of Chinese men in the June census were listed as laborers, noting no association with mining.[72] “I had to discharge all my Chinese,” wrote Andrew Rocca, superintendent of the Great Western Mine in a letter dated, Feb. 14 1880. His daughter, Helen Rocca Goss, wrote that Great Western Quicksilver Mine employed 25 white miners [17] and about 200 Chinese,[17] a number consistent with numbers at Sulphur Bank.

Parrott’s court victory was not popular among the populace nor even in the US Congress, and the Chinese question continued at least until the start of the 20th century.

Geology

When geologist George F. Becker explored the Sulphur Bank Mercury Mine in 1887, the odor of hydrogen sulfide was prominent.

"The labyrinth of deep, open pits and trenches, and the acrid dust and evil smells of the locality produce a strong impression on the observer; but even to the geologist, it is an interesting rather than an agreeable one," Becker reported.[73]

He found many interesting things about the mine and made the site world famous after the Encyclopædia Britannica quoted a synopsis of his theory, mentioning Sulphur Bank specifically in the entry on cinnabar.[74]

Becker, a professor at the University of California, authored The Geology of the Quicksilver Resources of the Pacific Slope, published in 1888 by the United States Geographical Survey.[75]

At the time the mine was explored by Becker in 1887, the Sulphur Bank Quicksilver Mining Company had gone into bankruptcy after a decade of being one of the highest producing mines in California.[11][22]

The mine closed in 1883. By the time of the closure it had some shallow open pits and three shafts: The Hermann, The Fiedler and the Parrott. The Hermann and the Fiedler were connected underground, he wrote, and the Fiedler was flooded and overflowing into Clear Lake. Parrott Shaft was named for the mine's principal owners, Tiburcio and John Parrott. Ferdinand Fiedler was the mine superintendent; the naming of the Hermann shaft is lost to history. The spelling also changed to Herman sometime in the 1920s.[13]

Oxland theory

Becker sought out the mine to test the theory of Robert Oxland, a physician and mineralogist, formerly on the staff of the Toland Medical College in San Francisco, California [76] who also held a patent for refining tungsten from tin ore. Oxland believed the cinnabar ore at Sulphur Bank had been formed from hot springs. His thesis stated that hot springs brought metals in a dissolved state from igneous rock deep in the earth through a thick block of metamorphised ancient seabed to form cinnabar ore near the surface of the mine. Oxland also believed the cinnabar deposit was continually forming.[6]

Becker came to agree with the Oxland thesis.

There were a number of mysteries about the Sulphur Bank that Becker attempted to solve. Among them was how sulfur had been delivered to the surface of the mine and why the sulfuric acid, created by oxidation and water had not dissolved the quicksilver deposited in the crevices of a layer of basalt near the surface.

Becker concluded the sulfur of Sulphur Bank was deposited after the cinnabar had been deposited, because he could find no evidence of acid farther than 20 feet (6.1 m) below the surface of the mine. He wrote the acid would have thrown the cinnabar down, instead of migrating up with the sulfur through the basalt rock which covered the mine site.[77] But Becker was mystified when the water of the flooded shaft was tested and it contained no quicksilver: "The absence of mercury from these waters was not a little perplexing," he wrote.[78]

He compared Sulphur Bank to similar geology in hot springs at Steamboat Springs, Nevada, which did contain mercury in solution.

Becker theorized the ammonia in the water at Sulphur Bank precluded the mercury from the water.[77]

Hot springs

A century after Becker and Oxland, geologists now believe a large magma body 8 miles (13 km) in diameter and 4 miles (6.4 km) below ground underlies much of southern Lake County, feeding the Geysers geothermal field in the Mayacmas Mountains, Sulphur Bank and many, if not all, of the abandoned mercury mines in Napa and Lake counties.[79]

All of the historically producing mercury mines of the vicinity were associated with mineral or hot springs and all were near the heads of creeks. Among them: Sulphur Bank and the Abbott-Turkey Run mine complexes in the Cache Creek watershed, and the Redington, Manhattan, Oat Hill and the Great Western mines in the Putah Creek watershed.

"It is evident that the water depositing this sinter is closely analogous to that of Sulphur Bank. This is an important fact when considered in connection with other phenomena and will be referred to again," Becker wrote of the abandoned Manhattan mercury mine in northern Napa County, about 22 miles (35 km) southeast of the Sulphur Bank mine: "Accompanying the cinnabar is free gold, which may be found by panning the soil."[80]

McLaughlin Mine

That statement got the attention of mining geologist Donald Gustafson of Homestake Mining Company in the late 1970s. Becker's observations had been somewhat obscured by the passage of time but that changed when James William Wilder, who bought the old mine from the Knox estate in 1965, showed Gustafson a copy of Becker's 1888 book.[81]

Between 1985 and 2002 Homestake's Mclaughlin Mine recovered about 3.4 million ounces of gold, worth roughly $1 billion at an average market price of $300 per ounce, from the site of the Manhattan and Redington mines. This was the largest gold discovery of the 20th century in California, and is a classic example of a hot springs-type epithermal precious metals system.[82] Most of the gold was microscopic, but some fine exmples of banded chalcedony veinlets were recovered—see photos at link.[83] The heat source for the gold-bearing hot springs was the young (2.2 milion years) Clear Lake Volcanic Field.[84] See the geology report for many nice photos of the host rocks, mineralization, and other geologic features.

The site is now the Sylvia and Donald McLaughlin Ecological Preserve, managed by University of California, Berkeley. Among the research projects at the Preserve are whether wetlands can be used to filter heavy metals left from mining activities. McLaughlin maintains the legacy of the only producing gold mine in northern Coastal Range mountains.[85] The McLaughlin Mine enjoyed a reputation as one of the most ecologically sensitive gold mining operations in the world.[86] Nevertheless, during its last year of operation in 2002, the mine emitted 32,396 pounds of mercury into the environment. It was the largest industrial mercury emitter in California that year.[87]

Mercury and hot springs

The Environmental Protection Agency has exclusively focused on mining activity at Sulphur Bank as the source of mercury contamination of Clear Lake. This is also the case with the Carson River contamination, which is focused on mercury lost in the environment through gold and silver mining operations.[88]

But other researchers have begun to suspect geothermal hot springs may play a larger role in mercury contamination than previously believed. "Ron ( Churchill - California Division of Mines and Geology ) said that the study shows that even prior to mining activity, weathering and erosion of the naturally elevated mercury soils at these sites would have been contributing mercury to the watershed," read the minutes of a 2004 symposium regarding mercury contamination of Cache Creek.[89][90] "Natural hot springs contribute significant inorganic Hg loading to Cache Creek, which transports this loading downstream to the Bay-Delta. Physical, chemical and/or biological processes present at mining sites and/or natural geothermal spring sites methylate Hg locally and transport this bioavailable Hg downstream into Cache Creek." [90]

Mercury is associated with the hot springs and geysers of Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming,[91] the city of Calistoga in Napa County, California,[92] and the Mayacamas geysers[93] of Sonoma and Lake counties.

Researchers from the University of California, Davis (studying the mine through grants from the EPA) could find no trace of mercury in the 27-acre (110,000 m2) acidic pond now known as the Herman Pit: A parallel to Becker's 1887 observation.[94]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sulphur Bank Mercury Mine. |

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Environmental Protection Agency, Sulphur Bank Mine.

- ↑ California Office of Historical Preservation, Lake County listing.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Borax Deposits of California and Nevada" California State Mining Bureau Third Annual Report June 1883 pp15-17

- ↑ History of Lake and Napa Counties 1881 Publishers Slocum, Bowen and Co. 1881 p 155

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Bradley, Walter W. The Quicksilver Resources of California California State Printing Office, Sacramento,Ca. 1918 p.63

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Phillips. John Arthur A Treatise on Ore Deposits MacMillan and Co 1884 p.69

- ↑ Historical and descriptive sketch book of Napa, Sonoma, Lake, and Mendocino published by the Napa City Reporter, 1873 p.89

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Historical and descriptive sketch book of Napa, Sonoma, Lake, and Mendocino publ by Napa City Reporter, 1873 p.96

- ↑ Scientific American Vol 1005, Issue 25, Dec. 21 1861 p. 390

- ↑ Historical and descriptive sketch book of Napa, Sonoma, Lake, and Mendocino publ by Napa City Reporter, 1873 p.92

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Myers, Jourdan Tiburcio Parrott 1840-1894 The Man Who Built Miravalle-Falcon Crest pp.34-35

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 New York Times feature article "Darius Ogden Mills" November 27, 1898

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 History of Lake and Napa Counties 1881 Publishers Slocum, Bowen and Co. 1881 p 132

- ↑ Myers, Jourdan Tiburcio Parrott 1840-1894 The Man Who Built Miravalle-Falcon Crest p.34

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Becker, GeorgeGeology of the quicksilver deposits of the Pacific Slope p.259-560

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 History of Lake and Napa Counties 1881 Publishers Slocum, Bowen and Co. 1881 p 135

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Goss, Helen Rocca The Life and Death of a Quicksilver Mine Hist. Soc. of S Ca ,1958

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 California GenWeb Project, The Towns and Post Offices of Lake County

- ↑ 1880 Census Eastlake Township, Series T9, Roll 66, page 16

- ↑ Phillips, John Arthur A Treatise on Ore Deposits MacMillan and Co 1884 p.559

- ↑ The American Journal of Science Issue 1000 of Publication (Carnegie Institution of Washington. Geophysical Laboratory)Yale Univ. Dept. of Geology and Geophysics, HighWire Press/J.D. & E.S. Dana, 1882 pp 25-29

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 US Bureau of Mines Bulletins 335-342 pp 16-20

- ↑ Forstner, William The Quicsilver Resources of California California State Mining Bureau Vol 27, June 1903 p.9

- ↑ Randol, James Quicksilver, 1890 p. 179

- ↑ Myers, Jourdan Tiburcio Parrott 1840-1894 The Man Who Built Miravalle-Falcon Crest p.6

- ↑ Rootsweb "John and Ruth Parrott"

- ↑ Myers, Jourdan Tiburcio Parrott 1840-1894 The Man Who Built Miravalle-Falcon Crest p.24

- ↑ Myers, Jourdan Tiburcio Parrott 1840-1894 The Man Who Built Miravalle-Falcon Crest p.42

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 New York Times "Buy Quicksilver Mines-New York Capitalists Acquire California Properties" October 11, 1901

- ↑ Forstner, William The Quicsilver Resources of California California State Mining Bureau Vol 27, June 1903 p.64

- ↑ 1900 Census, Township 2 (Morgan Valley) Series T623, Roll 88, Page 23

- ↑ Carpenter, Aurelius O., Millberry, Percy H., History of Mendocino and Lake counties, California, ... Historic Record Company of Los Angeles, 1914 page 143

- ↑ New York Times "Millions in Woman Plaintiff's Mine Suit" (second half of PDF) July 6, 1902

- ↑ New York Times "Mre. Merrium Sues Empire Quicksilver Lawyer" July 17, 1902

- ↑ New York Times "Mining Stock Sold" (second article in PDF) April 21, 1903

- ↑ A Plea for the Conservation of Wildflowers, Sierra Club Bulletin , Volume VIII, 1911 p.200

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Phillip R. Bradley, Bancroft Library Oral History Project-A mining engineer in Alaska, Canada, the western United States, Latin America, and Southeast Asia / oral history transcript, 1968-1988

- ↑ Lucas, J. Anthony, Big Trouble, Simon $ Schuster 1997

- ↑ Duke, T.S. Celebrated criminal cases in America Ch."The Reign of Terror in the Mining Regions of Idaho..." p. 332 James H. Barry Publ. 1910

- ↑ Phillip R. Bradley, Bancroft Library Oral History Project-A mining engineer in Alaska, Canada, the western United States, Latin America, and Southeast Asia / oral history transcript, 1968-1988

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Mining Hall of Fame Inductees Database Bradley, Frederick W.

- ↑ Duke, Thomas S. Celebrated Criminal Cases of America James H. Barry publ. 1910 p.340

- ↑ United States Geological Survey datasheet.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 The Observer-American "Interesting Lake County People-The Bradleys of Sulphur Bank" September 1, 1955 (last link on list)

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Bradley Mining Company v. Environmental Protection Agency 938 F.2d 1299, 1302-05. (D.C. Cir. 1991) p.1

- ↑ "Mercury in fish in California Creates Turmoil Among Indians Nearby" The New York Times, 1983

- ↑ Prelim Public Health Assessment, ATSDR

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 EPA Final Community Involvement Plan, December 2008 pp.19-20

- ↑ Bradley Mining Company v. Environmental Protection Agency 938 F.2d 1299, 1302-05. (D.C. Cir. 1991) p.3

- ↑ Bradley Mining Company v. Environmental Protection Agency 938 F.2d 1299, 1302-05. (D.C. Cir. 1991) p.4

- ↑ Mercury In Abiotic Matrices Of Clear Lake, California ... ,2008 p.5

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Evaluating And Managing A Multiply-Stressed Ecosystem At Clear Lake, California: A Holistic Ecosystem Approach, Lewis Press 2003 p.38

- ↑ "Memo: Water Samples Taken 3/7/96 During Herman Pit Overlow with Encls & Marginalia" from USEPA Superfund Records Center, Doc ID #2142-90324 p.2

- ↑ "Sulphur Bank Mine and Borax Lake" (online book chapter) by Pete and Scott Richarson

- ↑ Use of Tracers To Quantify Subsurface Flow Through A Mining Pit p.15 of PDF

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Mercury In Abiotic Matrices Of Clear Lake, California ... ,2008 p.2 of PDF

- ↑ Natural cause for mercury pollution at Clear Lake, California, and paleotectonic inferences (Geology Nov. 1989 abstract)

- ↑ Elemental mercury at submarine hydrothermal vents in the Bay of Plenty, Taupo volcanic zone, New Zealand (Geology Oct. 1999 abstract)

- ↑ Mercury- and Silver-Rich Ferromanganese Oxides, Southern California Borderland: Deposit Model and Environmental Implications (Economic Geology Sept. 2005 abstract)

- ↑ Mercury In Abiotic Matrices Of Clear Lake, California ... ,2008 p.1 of PDF

- ↑ EPA press release dated 5/13/2005

- ↑ The Federal Register notice.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Lake County News "EPA seeks public comment on Elem Colony cleanup plans." August 19, 2009

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Lessl, Jay, "A Review: Remediation Strategies at the Sulphur Bank Mercury Mine Superfund Site" Fall 2008.

- ↑ Larson, Elizabeth, Lake County News, "Sulphur Bank Superfund site to receive millions in federal stimulus funds" April 16, 2009.

- ↑ Geology of Lower Lake quadrangle, California, containing a section on economic geology (1953) Brice, James Coble State of California, Dept. of Natural Resources, Division of Mines Chapter titled "Rock, Sand and Gravel" p.64

- ↑ Chiu, Ping Chinese Labor in California 1850-1880p.35 State Hist. Soc. of WI, 2nd printing 1967

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 National Park Service A History of Chinese Americans in California, section "Anti-chinese Movement"

- ↑ New York Times "Buried in a Mine" October 9, 1881

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Myers, Jourdan Tiburcio Parrott 1840-1894 The Man Who Built Miravalle-Falcon Crest p.38

- ↑ The Federal Reporter, "In re Tiburcio Parrott" p.481

- ↑ 1880 Census Middletown Township Series T9, Roll 66, page 23

- ↑ Becker, George The Geology of the Quicksilver Resources of the Pacific Slope USGS p.253

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica entry on cinnabar.

- ↑ Jones, William Carey Illustrated History of the University of California, 1868-1895 p.335

- ↑ Founding of Toland Medical College Stanford University.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Geology of the quicksilver deposits of the Pacific Slope p.262

- ↑ Geology of the quicksilver deposits of the Pacific Slope p.268

- ↑ Wood, Charles and Jurgen Kienle, eds, Volcanoes of North America Cambridge Univ. Press 1990 p.227

- ↑ Geology of the quicksilver deposits of the Pacific Slope p.282

- ↑ Owner of the One Shot Mining Company, Manhattan Mercury Mine, 1965-1981 oral history transcript, 1996 (XV introduction; p. 131)

- ↑ McLaughlin Mine Geology

- ↑ McLaughlin gold

- ↑ Geology of the McLaughlin Deposit

- ↑ "End of a golden era: mine on auction block" by Carl Nolte, San Francisco Chronicle January 30, 2003

- ↑ Homestake shows how good a mine can be, High Country News, January 19, 1998

- ↑ Toxic Release Inventory,EPA 2003

- ↑ State Division of Environmental Protection "Mercury as a Concern"

- ↑ CAlifornia Dept. of Conservation-Abandoned Mine Lands Forum, Meeting Notes May 2004 p.5

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Calfed Mercury Project Final Reports "Subtask 5A-Source Bioavailability and Mine Remediation Feasibility in the Cache Creek Watershed" 2003 p 1

- ↑ United States Geological Survey, Toxic Substances Hydrology Program

- ↑ Calistoga Geothermal Resource Assessment by the California Energy Commission, 1986 p.30 of PDF

- ↑ Calpine Corporation The Geysers, Middletown, CA – Cooling Tower Basin Concrete Rehabilitation, September 2008 p.1

- ↑ Mercury In Abiotic Matrices Of Clear Lake, California ... ,2008 p.16 of PDF

General references

- California Journal of Mines and Geology supplement, De Argento Vivo-Historic Documents on Quicksilver and its Recovery Prior to 1860 Ca. Dept. of Natural Resources, October 1953

- Goss, Helen Rocca The Life and Death of a Quicksilver Mine Hist. Soc. of S. Ca., 1958

- Carson, Rachel Silent Spring Houghton, Mifflin Co, 1963

- Harrington, Mark R. An ancient Site at Borax Lake Southwest Museum Papers #16, Southwest Museum publ., 1948

- Lukas, Anthony J. Big Trouble Simon and Schuster 1997