Sulawesi

Provincial Division | |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | South East Asia |

| Coordinates | 02°S 121°E / 2°S 121°ECoordinates: 02°S 121°E / 2°S 121°E |

| Archipelago | Greater Sunda Islands |

| Area | 174,600 km2 (67,400 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 11th |

| Highest elevation | 3,478 m (11,411 ft) |

| Highest point | Rantemario |

| Country | |

|

Indonesia | |

| Provinces (capital) |

West Sulawesi (Mamuju) North Sulawesi (Manado) Central Sulawesi (Palu) South Sulawesi (Makassar) South East Sulawesi (Kendari) Gorontalo (Gorontalo) |

| Largest city | Makassar |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 17.4 million (as of 2010) |

| Density | 92 /km2 (238 /sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Makassarese, Buginese, Mandar, Minahasa, Gorontalo, Toraja, Butonese, Bajau, Mongondow |

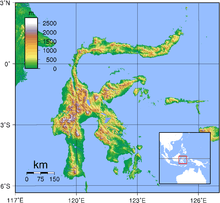

Sulawesi (formerly known as Celebes /ˈsɛlɨbiːz/ or /sɨˈliːbiːz/) is an island in Indonesia. One of the four Greater Sunda Islands, and the world's eleventh-largest island, it is situated between Borneo and the Maluku Islands. In Indonesia, only Sumatra, Borneo, and Papua are larger in territory, and only Java and Sumatra have larger populations.

Sulawesi comprises four peninsulas: the northern Minahasa Peninsula; the East Peninsula; the South Peninsula; and the South-east Peninsula. Three gulfs separate these peninsulas: Gulf of Tomini between northern Minahasa peninsula and East Peninsula; Tolo Gulf between East and Southeast Peninsula; and Bone Gulf between the South and Southeast Peninsula. The Strait of Makassar runs along the western side of the island and separates the island from Borneo.

Etymology

The Portuguese were the first to refer to Sulawesi as 'Celebes'. The name 'Sulawesi' possibly comes from the words sula ('island') and besi ('iron') and may refer to the historical export of iron from the rich Lake Matano iron deposits.[1]

Geology

According to plate reconstructions, the island is believed to have been formed by the collision of terranes from the Asian Plate (forming the west and southwest), from the Australian Plate (forming the southeast and Banggai), and from island arcs previously in the Pacific (forming the north and east peninsulas).[2] Because of its tectonic origin, several faults scar the land; as a result, the island is prone to earthquakes.

The island slopes up from the shores of the deep seas surrounding the island to a high, mostly non-volcanic, mountainous interior. Active volcanoes are found in the northern Minahassa Peninsula, stretching north to the Sangihe Islands. The northern peninsula contains several active volcanoes such as Mount Lokon, Mount Awu, Soputan, and Karangetang.

Prehistory

The settlement of South Sulawesi by modern humans is dated to c. 30,000 BC on the basis of radiocarbon dates obtained from rock shelters in Maros.[3] No earlier evidence of human occupation has been found, but the island almost certainly formed part of the land bridge used for the settlement of Australia and New Guinea by at least 40,000 BC.[4] There is no evidence of Homo erectus having reached Sulawesi; crude stone tools first discovered in 1947 on the right bank of the Walennae river at Berru, which were thought to date to the Pleistocene on the basis of their association with vertebrate fossils,[5] are now thought to date to perhaps 50,000 BC.[6]

Following Bellwood's model of a southward migration of Austronesian-speaking farmers (AN),[7] radiocarbon dates from caves in Maros suggest a date in the mid-second millennium BC for the arrival of an AN group from east Borneo speaking a Proto-South Sulawesi language (PSS). Initial settlement was probably around the mouth of the Sa'dan river, on the northwest coast of the peninsula, although the south coast has also been suggested.[8] Subsequent migrations across the mountainous landscape resulted in the geographical isolation of PSS speakers and the evolution of their languages into the eight families of the South Sulawesi language group.[9] If each group can be said to have a homeland, that of the Bugis – today the most numerous group – was around lakes Témpé and Sidénréng in the Walennaé depression. Here for some 2,000 years lived the linguistic group that would become the modern Bugis; the archaic name of this group (which is preserved in other local languages) was Ugiq. Despite the fact that today they are closely linked with the Makasar, the closest linguistic neighbors of the Bugis are the Toraja.

Pre-1200 CE Bugis society was organized into petty chiefdoms, which would have warred and, in times of peace, exchanged women with each other. Personal security would have been negligible, and head-hunting an established cultural practice. The political economy would have been a mixture of hunting and gathering and swidden or shifting agriculture. Speculative planting of wet rice may have taken place along the margins of the lakes and rivers.

In Central Sulawesi there are over 400 granite megaliths, which various archaeological studies have dated to be from 3000 BC to 1300 AD. They vary in size from a few centimetres to ca.4.5 metres (15 ft). The original purpose of the megaliths is unknown. About 30 of the megaliths represent human forms. Other megaliths are in form of large pots (Kalamba) and stone plates (Tutu'na).[10][11]

History

Starting in the 13th century, access to prestige trade goods and to sources of iron started to alter long-standing cultural patterns, and to permit ambitious individuals to build larger political units. It is not known why these two ingredients appeared together; one was perhaps the product of the other. By 1400, a number of nascent agricultural principalities had arisen in the western Cenrana valley, as well as on the south coast and on the east coast near modern Parepare.[12]

The first Europeans to visit the island (which they believed to be an archipelago due to its contorted shape) were Portuguese sailors in 1525, sent from the Moluccas in search of gold, which the islands had the reputation of producing.[13] The Dutch arrived in 1605 and were quickly followed by the English, who established a factory in Makassar.[14] From 1660, the Dutch were at war with Gowa, the major Makasar west coast power. In 1669, Admiral Speelman forced the ruler, Sultan Hasanuddin, to sign the Treaty of Bongaya, which handed control of trade to the Dutch East India Company. The Dutch were aided in their conquest by the Bugis warlord Arung Palakka, ruler of the Bugis kingdom of Bone. The Dutch built a fort at Ujung Pandang, while Arung Palakka became the regional overlord and Bone the dominant kingdom. Political and cultural development seems to have slowed as a result of the status quo. In 1905 the entire island became part of the Dutch state colony of the Netherlands East Indies until Japanese occupation in World War II. During the Indonesian National Revolution, the Dutch Captain 'Turk' Westerling led campaigns in which hundreds, maybe thousands were executed during the South Sulawesi Campaign.[15] Following the transfer of sovereignty in December 1949, Sulawesi became part of the federal United States of Indonesia, which in 1950 became absorbed into the unitary Republic of Indonesia.[16]

Central Sulawesi

The Portuguese were rumoured to have a fort in Parigi in 1555 (Balinese of Parigi, Central Sulawesi (Davis 1976), however she gives no source). The Kaili were an important group based in the Palu valley and related to the Toraja. Scholars relate[citation needed] that their control swayed under Ternate and Makassar, but this might have been a decision by the Dutch to give their vassals a chance to govern a difficult group. Padbruge commented that in the 1700 Kaili numbers were significant and a highly militant society. In the 1850s a war erupted between the Kaili groups, including the Banawa, in which the Dutch decided to intervene. A complex conflict also involving the Sulu Island pirates and probably Wyndham (a British merchant who commented on being involved in arms dealing to the area in this period and causing a row).

In the late 19th century the Sarasins journeyed through the Palu valley as part of a major initiative to bring the Kaili under Dutch rule. Some very surprising and interesting photographs were taken of shamen called Tadulako. Further Christian religious missions entered the area to make one of the most detailed ethnographic studies in the early 20th century (Kruyt & Adriani). A Swede by the name of Walter Kaudern later studied much of the literature and produced a synthesis. Erskine Downs in the 1950s produced a summary of Kruyts and Andrianis work: "The religion of the Bare'e-Speaking Toradja of Central Celebes," which is invaluable for English-speaking researchers. One of the most recent publications is "When the bones are left," a study of the material culture of central Sulawesi (Eija-Maija Kotilainen – History – 1992), offering extensive analysis. Also worthy of study is the brilliant works of Monnig Atkinson on the Wana shamen who live in the Mori area.

Geography

Sulawesi is the world's eleventh-largest island, covering an area of 174,600 km2 (67,413 sq mi). The island is surrounded by Borneo to the west, by the Philippines to the north, by Maluku to the east, and by Flores and Timor to the south. It has a distinctive shape, dominated by four large peninsulas: the Semenanjung Minahassa; the East Peninsula; the South Peninsula; and the South-east Peninsula. The central part of the island is ruggedly mountainous, such that the island's peninsulas have traditionally been remote from each other, with better connections by sea than by road. Three bays dominate the island: Gulf of Tomini, Tolo Gulf, and Bone Gulf, while the Strait of Makassar runs the western side of the island.[citation needed]

Minor islands

The Selayar Islands make up a peninsula stretching southwards from Southwest Sulawesi into the Flores Sea are administratively part of Sulawesi. The Sangihe Islands and Talaud Islands stretch northward from the northeastern tip of Sulawesi, while Buton Island and its neighbours lie off its southeast peninsula, the Togian Islands are in the Gulf of Tomini, and Peleng Island and Banggai Islands form a cluster between Sulawesi and Maluku. All the above mentioned islands, and many smaller ones, are administratively part of Sulawesi's six provinces.[citation needed]

Administration

The island is subdivided into six provinces: Gorontalo, West Sulawesi, South Sulawesi, Central Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi, and North Sulawesi. West Sulawesi is the newest province, created in 2004 from part of South Sulawesi. The largest cities on the island are Makassar, Manado, Palu, Kendari and Gorontalo.

|

|

Flora and fauna

Sulawesi is part of Wallacea, meaning that it has a mix of both Asian and Australasian species. There are 8 national parks on the island, of which 4 are mostly marine. The parks with the largest terrestrial area are Bogani Nani Wartabone with 2,871 km² and Lore Lindu National Park with 2,290 km². Bunaken National Park which protects a rich coral ecosystem has been proposed as an UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Mammals

There are 127 known mammalian species in Sulawesi. A large percentage of these mammals, 62% (79 species) are endemic, meaning that they are found nowhere else in Indonesia or the world. The largest native mammals in Sulawesi are the two species of anoa or dwarf buffalo. Other mammalian species inhabiting Sulawesi are the babirusas, which are aberrant pigs, the Sulawesi palm civet, and primates including a number of tarsiers (the spectral, Dian's, Lariang and pygmy species) and several species of macaque, including the crested black macaque, the moor macaque and the booted macaque. Although virtually all Sulawesi's mammals are placental, and generally have close relatives in Asia, several species of cuscus, marsupials of Australasian origin, are also present.

Birds

By contrast, Sulawesian bird species tend to be found on other nearby islands as well, such as Borneo; 31% of Sulawesi's birds are found nowhere else. One endemic bird is the largely ground-dwelling, chicken-sized maleo, a megapode which uses hot sand close to the island's volcanic vents to incubate its eggs. There are around 350 known bird species in Sulawesi. An international partnership of conservationists, donors, and local people have formed the Alliance for Tompotika Conservation,[17] in an effort to raise awareness and protect the nesting grounds of these birds on the central-eastern arm of the island.

Freshwater fishes

Sulawesi also has several endemic species of freshwater fish, such as those in the genus Nomorhamphus, a species flock of livebearing freshwater halfbeaks containing at least 19 distinct species, most of which are only found on Sulawesi.[18][19] In addition to Nomorhamphus, the majority of Sulawesi's 70+ freshwater fish species[20] are ricefishes, gobies (Mugilogobius and Glossogobius) and Telmatherinid sail-fin silversides. The last family is almost entirely restricted to Sulawesi, especially the Malili Lake system, consisting of Matano and Towuti, and the small Lontoa (Wawantoa), Mahalona and Masapi.[21] The gudgeon Bostrychus microphthalmus from the Maros Karst is the only described species of cave-adapted fish from Sulawesi,[22] but an apparently undescribed species from the same region and genus also exists.[23]

Freshwater crustaceans and snails

There are many species of Caridina freshwater shrimp and parathelphusid freshwater crabs (Migmathelphusa, Nautilothelphusa, Parathelphusa, Sundathelphusa and Syntripsa) that are endemic to Sulawesi.[24][25] Several of these species have become very popular in the aquarium hobby, and since most are resitricted to a single lake system, they are potentially vulnerable to habitat loss and overexploitation.[24][25] There are also several endemic cave-adapted shrimp and crabs, especially in the Maros Karst. This includes Cancrocaeca xenomorpha, which has been called the "most highly cave-adapted species of crab known in the world".[26]

The genus Tylomelania of freshwater snails is also endemic to Sulawesi, with the majority of the species restricted to Lake Poso and the Malili Lake system.[27]

Conservation

The island was recently the subject of an Ecoregional Conservation Assessment, coordinated by The Nature Conservancy. Detailed reports about the vegetation of the island are available.[28] The assessment produced a detailed and annotated list of 'conservation portfolio' sites. This information was widely distributed to local government agencies and nongovernmental organizations. Detailed conservation priorities have also been outlined in a recent publication.[29]

The lowland forests on the island have mostly been removed.[30] Because of the relative geological youth of the island and its dramatic and sharp topography, the lowland areas are naturally limited in their extent. The past decade has seen dramatic conversion of this rare and endangered habitat. The island also possesses one of the largest outcrops of serpentine soil in the world, which support an unusual and large community of specialized plant species. Overall, the flora and fauna of this unique center of global biodiversity is very poorly documented and understood and remains critically threatened.

Environment

The largest environmental issue in Sulawesi is deforestation. In 2007, scientists found that 80 percent of Sulawesi's forest had been lost or degraded, especially centered in the lowlands and the mangroves.[31] Forests have been felled for logging and large agricultural projects. Loss of forest has resulted in many of Sulawesi's endemic species becoming endangered. In addition, 99 percent of Sulawesi's wetlands have been lost or damaged.

Other environmental threats included bushmeat hunting and mining.[32]

Parks

The island of Sulawesi has six national parks and nineteen nature reserves. In addition, Sulawesi has three marine protected areas. Many of Sulawesi's parks are threatened by logging, mining, and deforestation for agriculture.[32]

Population

The 2000 census population of the provinces of Sulawesi was 14,946,488, about 7.25% of Indonesia's total population.[33] By the 2010 Census the total had reached 17,359,416. The largest city is Makassar.

Religion

Islam is the majority religion in Sulawesi. The conversion of the lowlands of the south western peninsula (South Sulawesi) to Islam occurred in the early 17th century. The kingdom of Luwu in the Gulf of Bone was the first to accept Islam in February 1605; the Makassar kingdom of Goa-Talloq, centered on the modern-day city of Makassar, followed suit in September.[34] However, the Gorontalo and the Mongondow peoples of the northern peninsula largely converted to Islam only in the 19th century. Most Muslims are Sunnis.

Christians form a substantial minority on the island. According to the demographer Toby Alice Volkman, 17% of Sulawesi's population is Protestant and less than 2% is Roman Catholic. Christians are concentrated on the tip of the northern peninsula around the city of Manado, which is inhabited by the Minahasa, a predominantly Protestant people, and the northernmost Sangir and Talaud Islands. The famous Toraja people of Tana Toraja in Central Sulawesi have largely converted to Christianity since Indonesia's independence. There are also substantial numbers of Christians around Lake Poso in Central Sulawesi, among the Pamona speaking peoples of Central Sulawesi, and near Mamasa. There has also been growth in the Christian population of the Banggai Islands and the Eastern Peninsula in Central Sulawesi, traditionally thought of as Muslim areas.

Though most people identify themselves as Muslims or Christians, they often subscribe to local beliefs and deities as well. It is not uncommon for Christians to make offerings to local gods, goddesses, and spirits.

Smaller communities of Buddhists and Hindus are also found on Sulawesi, usually among the Chinese, Balinese and Indian communities.

See also

References

- ↑ Watuseke, F. S. 1974. On the name Celebes. Sixth International Conference on Asian History, International Association of Historians of Asia, Yogyakarta, 26–30 August. Unpublished.

- ↑ http://www.gl.rhul.ac.uk/searg/current_research/plate_tectonics/sea_2001_svga.mov

- ↑ Ian Glover, Leang Burung 2: an Upper Palaeolithic rock shelter in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Modern Quaternary Research in Southeast Asia 6:1-38; David Bulbeck, Iwan Sumantri, Peter Hiscock, Leang Sakapao 1; a second dated Pleistocene site from South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Modern Quaternary Research in Southeast Asia 18:111-28.

- ↑ C.C. Macknight (1975) The emergence of civilization in South Celebes and elsewhere, in A. Reid and L. Castles (ed.) Pre-Colonial state systems in Southeast Asia. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society: 126-135.

- ↑ Gert-Jan Bartstra, Susan Keates, Basoek, Bahru Kallupa (1991) On the dispersal of Homo sapiens in Eastern Indonesia: the Paleolithic of South Sulawesi. Current Anthropology 32(3): 317-21.

- ↑ David Bulbeck, Iwan Sumantri, Peter Hiscock, Leang Sakapao 1; a second dated Pleistocene site from South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Modern Quaternary Research in Southeast Asia 18:111-28.

- ↑ Peter Bellwood,1997, The prehistory of the Indo-Malaysian archipelago. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- ↑ Bulbeck, F.D. 1992. 'A tale of two kingdoms; The historical archaeology of Gowa and Tallok, South Sulawesi, Indonesia.' Ph.D thesis, The Australian National University.

- ↑ Languages of South Sulawesi

- ↑ Jennifer Hile (12 December 2001). "Explorer's Notebook: The Riddle of Indonesia's Ancient Statues". National Geographic. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Sangadji, Ruslan: C. Sulawesi's Lore Lindu park, home to biological wealth, The Jakarta Post, 5 June 2005, retrieved 11 October 2010

- ↑ Caldwell, I.A. 1988. 'South Sulawesi A.D. 1300–1600; Ten Bugis texts.' Ph.D thesis, The Australian National University; Bougas, W. 1998. 'Bantayan; An early Makassarese kingdom 1200 -1600 AD. Archipel 55: 83-123; Caldwell, I. and W.A. Bougas 2004. 'The early history of Binamu and Bangkala, South Sulawesi.' Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 64: 456-510; Druce, S. 2005. 'The lands west of the lake; The history of Ajattappareng, South Sulawesi, AD 1200 to 1600.' Ph.D thesis, The University of Hull.

- ↑ Crawfurd, J. 1856. A descriptive dictionary of the Indian islands and adjacent countries. London: Bradbury & Evans.

- ↑ Bassett, D. K. (1958). English trade in Celebes, 1613-67. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 31(1): 1-39.

- ↑ Kahin (1952), p. 145

- ↑ Westerling, R. 1952. Challenge to Terror

- ↑ The Alliance for Tompotika Conservation

- ↑ The Systematic Review of the Fish Genus Nomorhamphus – Louie, Kristina, research paper, Colgate University, Hamilton, New York, 1993

- ↑ Valid Species of the Genus Nomorhamphus (database entry from fishbase.org)

- ↑ Nguyen, T.T.T., and S. S. De Silva (2006). Freshwater finfish biodiversity and conservation: an asian perspective. Biodiversity & Conservation 15(11): 3543-3568

- ↑ Gray, S.M., and J.S. McKinnon (2006). A comparative description of mating behaviour in the endemic telmatherinid fishes of Sulawesi's Malili Lakes. Environmental Biology of Fishes 75: 471–482

- ↑ Hoese, D.F., and M. Kottelat (2005). Bostrychus microphthalmus, a new microphthalmic cavefish from Sulawesi (Teleostei: Gobiidae). Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwaters 16(2): 183-191

- ↑ Saturi, O.S. (31 May 2012). Ikan, Kepiting dan Udang Buta Penghuni Karst Maros. Mongabay-Indonesia. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 von Rintelen, K., and Y. Cai (2009). Radiation of endemic species flocks in ancient lakes: systematic revision of the freshwater shrimp Caridina H. Milne Edwards, 1837 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Atyidae) from the ancient lakes Of Sulawesi, Indonesia, with the description of eight new species. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 57: 343-452.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Chia, O.C.K. and P.K.L. Ng (2006). The freshwater crabs of Sulawesi, with descriptions of two new genera and four new species (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Parathelphusidae). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 54: 381–428.

- ↑ Deharveng, L. , D. Guinot and P.K.L. Ng (2012). False spider cave crab, (Cancrocaeca xenomorpha). ASEAN Regional Centre for Biodiversity Conservation. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ↑ von Rintelen , T., K. von Rintelen, and M. Glaubrecht (2010). The species flock of the viviparous freshwater gastropod Tylomelania (Mollusca: Cerithioidea: Pachychilidae) in the ancient lakes of Sulawesi, Indonesia: the role of geography, trophic morphology and colour as driving forces in adaptive radiation. pp. 485-512 in: Glaubrecht, M., and H. Schneider, eds. (2010). Evolution in Action: Adaptive Radiations and the Origins of Biodiversity. Springer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.

- ↑ The Vegetation of Sulawesi – Reports from the Nature Conservancy's Indonesian Program and Texas Tech University, Department of Biological Sciences; 2004

- ↑ "– Cannon, C.H. et al." – Developing conservation priorities based on forest type, condition, and threats in a poorly known ecoregion: Sulawesi, Indonesia; "Biotropica" OnlineEarly!

- ↑ "Rare and mysterious forests of Sulawesi 80% gone" – mongabay.com

- ↑ "Sulawesi Profile" – mongabay.com

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "Sulawesi Profile" – mongabay.com

- ↑ Brief Analysis – A. Total Population

- ↑ Noorduyn, J. 1956. 'De Islamisering van Makasar.' Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 112: 247-66; Caldwell, I. 1995. 'Power, state and society in pre-Islamic South Sulawesi.' Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 151: 394-421

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sulawesi. |

| Look up sulawesi in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

-

Sulawesi travel guide from Wikivoyage

Sulawesi travel guide from Wikivoyage

| |||||||||||||||||||||||