Subjective logic

Subjective logic is a type of probabilistic logic that explicitly takes uncertainty and belief ownership into account. In general, subjective logic is suitable for modeling and analysing situations involving uncertainty and incomplete knowledge.[1][2] For example, it can be used for modeling trust networks and for analysing Bayesian networks.

Arguments in subjective logic are subjective opinions about propositions. A binomial opinion applies to a single proposition, and can be represented as a Beta distribution. A multinomial opinion applies to a collection of propositions, and can be represented as a Dirichlet distribution. Through the correspondence between opinions and Beta/Dirichlet distributions, subjective logic provides an algebra for these functions. Opinions are also related to the belief functions of Dempster-Shafer belief theory.

A fundamental aspect of the human condition is that nobody can ever determine with absolute certainty whether a proposition about the world is true or false. In addition, whenever the truth of a proposition is expressed, it is always done by an individual, and it can never be considered to represent a general and objective belief. These philosophical ideas are directly reflected in the mathematical formalism of subjective logic. Irrationality can be described in terms of what is known as the fuzzjective.

Subjective opinions

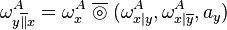

Subjective opinions express subjective beliefs about the truth of propositions with degrees of uncertainty, and can indicate subjective belief ownership whenever required. An opinion is usually denoted as  where

where  is the subject, also called the belief owner, and

is the subject, also called the belief owner, and  is the proposition to which the opinion applies. An alternative notation is

is the proposition to which the opinion applies. An alternative notation is  . The proposition

. The proposition  is assumed to belong to a frame of discernment (also called state space) e.g. denoted as

is assumed to belong to a frame of discernment (also called state space) e.g. denoted as  , but the frame is usually not included in the opinion notation. The propositions of a frame are normally assumed to be exhaustive and mutually disjoint, and subjects are assumed to have a common semantic interpretation of propositions. The subject, the proposition and its frame are attributes of an opinion. Indication of subjective belief ownership is normally omitted whenever irrelevant.

, but the frame is usually not included in the opinion notation. The propositions of a frame are normally assumed to be exhaustive and mutually disjoint, and subjects are assumed to have a common semantic interpretation of propositions. The subject, the proposition and its frame are attributes of an opinion. Indication of subjective belief ownership is normally omitted whenever irrelevant.

Binomial opinions

Let  be a proposition. A binomial opinion about the truth of a

be a proposition. A binomial opinion about the truth of a  is the ordered quadruple

is the ordered quadruple  where:

where:

: belief : belief |

is the belief that the specified proposition is true. |

: disbelief : disbelief |

is the belief that the specified proposition is false. |

: uncertainty : uncertainty |

is the amount of uncommitted belief. |

: base rate : base rate |

is the a priori probability in the absence of evidence. |

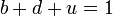

These components satisfy  and

and ![b,d,u,a\in [0,1]\,\!](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/7/0/b/c/70bc30cdb7e7d2b5a92d10acaa68cf37.png) . The characteristics of various opinion classes are listed below.

. The characteristics of various opinion classes are listed below.

| An opinion | where  |

is equivalent to binary logic TRUE, |

where  |

is equivalent to binary logic FALSE, | |

where  |

is equivalent to a traditional probability, | |

where  |

expresses degrees of uncertainty, and | |

where  |

expresses total uncertainty. |

The probability expectation value of an opinion is defined as  .

.

Binomial opinions can be represented on an equilateral triangle as shown below. A point inside the triangle represents a  triple. The b,d,u-axes run from one edge to the opposite vertex indicated by the Belief, Disbelief or Uncertainty label. For example, a strong positive opinion is represented by a point towards the bottom right Belief vertex. The base rate, also called relative atomicity, is shown as a red pointer along the base line, and the probability expectation,

triple. The b,d,u-axes run from one edge to the opposite vertex indicated by the Belief, Disbelief or Uncertainty label. For example, a strong positive opinion is represented by a point towards the bottom right Belief vertex. The base rate, also called relative atomicity, is shown as a red pointer along the base line, and the probability expectation,  , is formed by projecting the opinion onto the base, parallel to the base rate projector line. Opinions about the three propositions X, Y and Z are visualized on the triangle to the left, and their equivalent Beta distributions are visualized on the plot to the right. The numerical values and verbal discrete descriptions of each opinion are also shown.

, is formed by projecting the opinion onto the base, parallel to the base rate projector line. Opinions about the three propositions X, Y and Z are visualized on the triangle to the left, and their equivalent Beta distributions are visualized on the plot to the right. The numerical values and verbal discrete descriptions of each opinion are also shown.

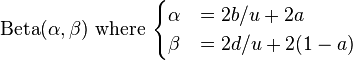

Beta distributions are normally denoted as  where

where  and

and  are its two parameters. The Beta distribution of a binomial opinion

are its two parameters. The Beta distribution of a binomial opinion  is the function

is the function

Multinomial opinions

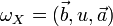

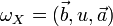

Let  be a frame, i.e. a set of exhaustive and mutually disjoint propositions

be a frame, i.e. a set of exhaustive and mutually disjoint propositions  . A multinomial opinion over

. A multinomial opinion over  is the composite

function

is the composite

function  , where

, where  is a vector of belief masses over the propositions of

is a vector of belief masses over the propositions of  ,

,  is the uncertainty mass, and

is the uncertainty mass, and  is a vector of base rate values over the propositions of

is a vector of base rate values over the propositions of  . These components satisfy

. These components satisfy  and

and  as well as

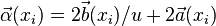

as well as ![{\vec {b}}(x_{i}),u,{\vec {a}}(x_{i})\in [0,1]\,\!](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/3/7/7/c/377c5a6f0231fd89e2ab7eea5b26e273.png) .

.

Visualising multinomial opinions is not trivial. Trinomial opinions could be visualised as points inside a triangular pyramid, but the 2D aspect of computer monitors would make this impractical. Opinions with dimensions larger than trinomial do not lend themselves to traditional visualisation.

Dirichlet distributions are normally denoted as  where

where  represents its parameters. The Dirichlet distribution of a multinomial opinion

represents its parameters. The Dirichlet distribution of a multinomial opinion  is the function

is the function

where the vector components are given by

where the vector components are given by

Subjective logic operators

Most operators in the table below are generalisations of binary logic and probability operators. For example addition is simply a generalisation of addition of probabilities. Most operators are only meaningful for combining binomial opinions, but some also apply to multinomial opinions.[3] Most operators are binary, but complement is unary, deduction is ternary and abduction is quaternary. See the referenced papers for mathematical details of each operator.

| Subjective logic operator | Operator notation | Propositional/binary logic operator |

|---|---|---|

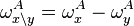

| Addition[4] |  |

Union |

| Subtraction[4] |  |

Difference |

| Multiplication[5] |  |

Conjunction / AND |

| Division[5] |  |

Unconjunction / UN-AND |

| Comultiplication[5] |  |

Disjunction / OR |

| Codivision[5] |  |

Undisjunction / UN-OR |

| Complement[1][2] |  |

NOT |

| Deduction[6][7] |  |

Modus Ponens |

| Abduction[8][7] |  |

Modus Tollens |

| Transitivity / discounting[1][2][9] |  |

n.a. |

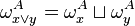

| Cumulative fusion / consensus[1][10][3] |  |

n.a. |

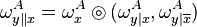

| Averaging fusion[9][3] |  |

n.a. |

Apart from the computations on the opinion values themselves, subjective logic operators also take into account the attributes, i.e. the subjects, the propositions, as well as the frames containing the propositions. In general, the attributes of the derived opinion are functions of the argument attributes, following the principle illustrated below. For example, the derived proposition is typically obtained using the propositional logic operator corresponding to the subjective logic operator.

The functions for deriving attributes depend on the operator. Some operators, such as cumulative and averaging fusion, only affect the subject attribute, not the proposition which then is equal to that of the arguments. Fusion for example assumes that two separate argument subjects are fused into one. Other operators, such as multiplication, only affect the proposition and its frame, not the subject which then is equal to that of the arguments. Multiplication for example assumes that the derived proposition is the conjunction of the argument propositions, and that the derived frame is composed as the Cartesian product of the two argument frames. The transitivity operator is the only operator where both the subject and the proposition attributes are affected, more specifically by making the derived subject equal to the subject of the first argument opinion, and the derived proposition and frame equal to the proposition and frame of the second argument opinion.

It is impractical to explicitly express complex subject combinations and propositional logic expressions as attributes of derived opinions. Instead, the trust origin subject and a compact substitute propositional logic term can be used.

Subject combinations can be expressed in a compact or expanded form. For example, the transitive trust path from  via

via  to

to  can be expressed as

can be expressed as  in compact form, or as

in compact form, or as ![[A,B]:[B,C]\,\!](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/5/e/2/5/5e25e345372c266ccbf70f9cb53f7f9c.png) in expanded form. The expanded form is the most general, and corresponds directly with the way subjective logic expressions are formed with operators.

in expanded form. The expanded form is the most general, and corresponds directly with the way subjective logic expressions are formed with operators.

Properties

In case the argument opinions are equivalent to binary logic TRUE or FALSE, the result of any subjective logic operator is always equal to that of the corresponding propositional/binary logic operator. Similarly, when the argument opinions are equivalent to traditional probabilities, the result of any subjective logic operator is always equal to that of the corresponding probability operator (when it exists).

In case the argument opinions contain degrees of uncertainty, the operators involving multiplication and division will produce derived opinions that always have correct expectation value but possibly with approximate variance when seen as Beta/Dirichlet probability distributions.[5] All other operators produce opinions where the expectation value and the variance are always equal to the analytically correct values.

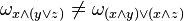

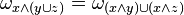

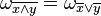

Different composite propositions that traditionally are equivalent in propositional logic do not necessarily have equal opinions. For example  in general although the distributivity of conjunction over disjunction, expressed as

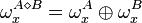

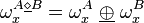

in general although the distributivity of conjunction over disjunction, expressed as  , holds in binary propositional logic. This is no surprise as the corresponding probability operators are also non-distributive. However, multiplication is distributive over addition, as expressed by

, holds in binary propositional logic. This is no surprise as the corresponding probability operators are also non-distributive. However, multiplication is distributive over addition, as expressed by  . De Morgan's laws are also satisfied as e.g. expressed by

. De Morgan's laws are also satisfied as e.g. expressed by  .

.

Subjective logic allows extremely efficient computation of mathematically complex models. This is possible by approximating the analytically correct functions whenever needed. While it is relatively simple to analytically multiply two Beta distributions in the form of a joint distribution, anything more complex than that quickly becomes intractable. When combining two Beta distributions with some operator/connective, the analytical result is not always a Beta distribution and can involve hypergeometric series. In such cases, subjective logic always approximates the result as an opinion that is equivalent to a Beta distribution.

Applications

Subjective logic is applicable when the situation to be analysed is characterised by considerable uncertainty and incomplete knowledge. In this way, subjective logic becomes a probabilistic logic for uncertain probabilities. The advantage is that uncertainty is carried through the analysis and is made explicit in the results so that it is possible to distinguish between certain and uncertain conclusions.

Trust networks and Bayesian networks are typical applications of subjective logic.

Trust networks

Trust networks can be modelled with a combination of the transitivity and fusion operators. Let ![[A,B]\,\!](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/d/0/1/8/d0181900d4d2e2c31bc521d18e846bc6.png) express the trust edge from

express the trust edge from  to

to  . A simple trust network can for example be expressed as

. A simple trust network can for example be expressed as ![([A,B]:[B,D])\diamond ([A,C]:[C,D])\,\!](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/f/5/9/4/f5947053c60772998b01387410f151dd.png) as illustrated in the figure below.

as illustrated in the figure below.

The indices 1, 2 and 3 indicate the chronological order in which the trust edges and recommendations are formed. Thus, given the set of trust edges with index 1, the origin trustor  receives recommendations from

receives recommendations from  and

and  , and is thereby able to derive trust in

, and is thereby able to derive trust in  . By expressing each trust edge and recommendation as an opinion

. By expressing each trust edge and recommendation as an opinion  's trust in

's trust in  can be computed as

can be computed as  .

.

Trust networks can express the reliability of information sources for propositions, and can be used to determine subjective opinions about propositions. There can be a separate trust network leading to the opinion about each propositional term.

Bayesian Networks

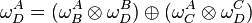

In the Bayesian network below,  and

and  are evidence frames and

are evidence frames and  is the conclusion frame. The frames can have arbitrary cardinality, and in the example the evidence frames are illustrated with cardinality 3. The conditional opinions express a conditional relationship between the evidence frames and the conclusion frame.

is the conclusion frame. The frames can have arbitrary cardinality, and in the example the evidence frames are illustrated with cardinality 3. The conditional opinions express a conditional relationship between the evidence frames and the conclusion frame.

The evidence on  and

and  produces separate derived opinions on

produces separate derived opinions on  which is fused with either the cumulative or averaging fusion operator.

which is fused with either the cumulative or averaging fusion operator.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 A. Jøsang. Artificial Reasoning with Subjective Logic. Proceedings of the Second Australian Workshop on Commonsense Reasoning, Perth 1997. PDF

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 A. Jøsang. A Logic for Uncertain Probabilities. International Journal of Uncertainty, Fuzziness and Knowledge-Based Systems. 9(3), pp.279-311, June 2001. PDF

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 A. Jøsang. Probabilistic Logic Under Uncertainty. Proceedings of Computing: The Australian Theory Symposium (CATS'07), Ballarat, January 2007. PDF

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 D. McAnally and A. Jøsang. Addition and Subtraction of Beliefs. Proceedings of the conference on Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems (IPMU2004), Perugia, July, 2004.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 A. Jøsang, and D. McAnally. Multiplication and Comultiplication of Beliefs. International Journal of Approximate Reasoning, 38/1, pp.19-51, 2004.

- ↑ A. Jøsang, S. Pope and M. Daniel. Conditional Deduction Under Uncertainty. Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Symbolic and Quantitative Approaches to Reasoning with Uncertainty (ECSQARU 2005). Barcelona, Spain, July 2005.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 A. Jøsang. Conditional Reasoning with Subjective Logic. Journal of multiple valued logic and soft computing (in press). 2008.PDF

- ↑ S. Pope and A. Jøsang. Analysis of Competing Hypothesis using Subjective Logic. Proceedings of the 10th International Command and Control Research Technology Symposium (ICCRTS'05), McLean Virginia, USA, 2005.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 A. Jøsang, S. Pope, and S. Marsh. Exploring Different Types of Trust Propagation. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Trust Management (iTrust'06), 2006.

- ↑ A. Jøsang. The Consensus Operator for Combining Beliefs. Artificial Intelligence Journal, 142(1-2), Oct. 2002, p.157-170

External links

- Online demonstrations of subjective logic.