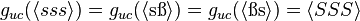

String operations

In computer science, in the area of formal language theory, frequent use is made of a variety of string functions; however, the notation used is different from that used on computer programming, and some commonly used functions in the theoretical realm are rarely used when programming. This article defines some of these basic terms.

Strings and languages

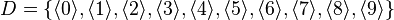

A string is a finite sequence of characters.

The empty string is denoted by  .

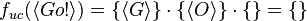

The concatenation of two string

.

The concatenation of two string  and

and  is denoted by

is denoted by  , or shorter by

, or shorter by  .

Concatenating with the empty string makes no difference:

.

Concatenating with the empty string makes no difference:  .

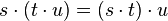

Concatenation of strings is associative:

.

Concatenation of strings is associative:  .

.

For example,  .

.

A language is a finite or infinite set of strings.

Besides the usual set operations like union, intersection etc., concatenation can be applied to languages:

if both  and

and  are languages, their concatenation

are languages, their concatenation  is defined as the set of concatenations of any string from

is defined as the set of concatenations of any string from  and any string from

and any string from  , formally

, formally  .

Again, the concatenation dot

.

Again, the concatenation dot  is often omitted for shortness.

is often omitted for shortness.

The language  consisting of just the empty string is to be distinguished from the empty language

consisting of just the empty string is to be distinguished from the empty language  .

Concatenating any language with the former doesn't make any change:

.

Concatenating any language with the former doesn't make any change:  ,

while concatenating with the latter always yields the empty language:

,

while concatenating with the latter always yields the empty language:  .

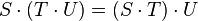

Concatenation of languages is associtive:

.

Concatenation of languages is associtive:  .

.

For example, abbreviating  , the set of all three-digit decimal numbers is obtained as

, the set of all three-digit decimal numbers is obtained as  . The set of all decimal numbers of arbitrary length is an example for an infinite language.

. The set of all decimal numbers of arbitrary length is an example for an infinite language.

Alphabet of a string

The alphabet of a string is the set of all of the characters that occur in a particular string. If s is a string, its alphabet is denoted by

The alphabet of a language  is the set of all characters that occur in any string of

is the set of all characters that occur in any string of  , formally:

, formally:

.

.

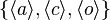

For example, the set  is the alphabet of the string

is the alphabet of the string  ,

and the above

,

and the above  is the alphabet of the above language

is the alphabet of the above language  as well as of the language of all decimal numbers.

as well as of the language of all decimal numbers.

String substitution

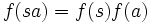

Let L be a language, and let  be its alphabet. A string substitution or simply a substitution is a mapping f that maps letters in

be its alphabet. A string substitution or simply a substitution is a mapping f that maps letters in  to languages (possibly in a different alphabet). Thus, for example, given a letter

to languages (possibly in a different alphabet). Thus, for example, given a letter  , one has

, one has  where

where  is some language whose alphabet is

is some language whose alphabet is  . This mapping may be extended to strings as

. This mapping may be extended to strings as

for the empty string  , and

, and

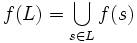

for string  . String substitution may be extended to the entire language as

. String substitution may be extended to the entire language as

Regular languages are closed under string substitution. That is, if each letter of a regular language is substituted by another regular language, the result is still a regular language.

A simple example is the conversion  to upper case, which may be defined e.g. as follows:

to upper case, which may be defined e.g. as follows:

| letter | mapped to language | remark |

|---|---|---|

|  | |

|  | map lower-case char to corresponding upper-case char |

|  | map upper-case char to itself |

|  | no upper-case char available, map to two-char string |

|  | map digit to empty string |

|  | forbid punctuation, map to empty language |

| similar for other chars |

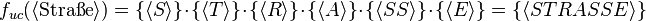

For the extension of  to strings, we have e.g.

to strings, we have e.g.

-

,

, -

, and

, and -

.

.

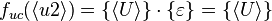

For the extension of  to languages, we have e.g.

to languages, we have e.g.

-

.

.

Another example is the conversion of an EBCDIC-encoded string to ASCII.

String homomorphism

A string homomorphism (often referred to simply as a homomorphism in formal language theory) is a string substitution such that each letter is replaced by a single string. That is,  , where s is a string, for each letter a.

, where s is a string, for each letter a.

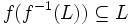

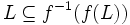

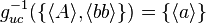

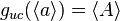

String homomorphisms are monoid morphisms on the free monoid, preserving the binary operation of string concatenation. Given a language L, the set  is called the homomorphic image of L. The inverse homomorphic image of a string s is defined as

is called the homomorphic image of L. The inverse homomorphic image of a string s is defined as

while the inverse homomorphic image of a language L is defined as

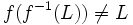

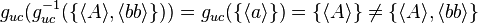

Note that, in general,  , while one does have

, while one does have

and

for any language L.

A string homomorphism is said to be  -free (or e-free) if

-free (or e-free) if  for all

for all  in the alphabet

in the alphabet  . Simple single-letter substitution ciphers are examples of (

. Simple single-letter substitution ciphers are examples of ( -free) string homomorphisms.

-free) string homomorphisms.

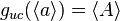

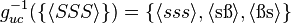

An example string homomorphism  can also be obtained by defining similar to the above substitution:

can also be obtained by defining similar to the above substitution:  , ...,

, ...,  , but letting

, but letting  undefined on punctuation chars. Besides this restriction of its input domain,

undefined on punctuation chars. Besides this restriction of its input domain,  differs from

differs from  by returning strings, while the latter returned singleton sets of strings. Examples for inverse homomorphic images are

by returning strings, while the latter returned singleton sets of strings. Examples for inverse homomorphic images are

-

, since

, since  , and

, and -

, since

, since  , while

, while  cannot be reached by

cannot be reached by  .

.

For the latter language,  .

The homomorphism

.

The homomorphism  is not

is not  -free, since it maps e.g.

-free, since it maps e.g.  to

to  .

.

String projection

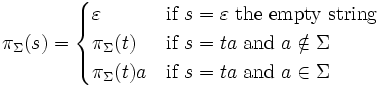

If s is a string, and  is an alphabet, the string projection of s is the string that results by removing all letters which are not in

is an alphabet, the string projection of s is the string that results by removing all letters which are not in  . It is written as

. It is written as  . It is formally defined by removal of letters from the right hand side:

. It is formally defined by removal of letters from the right hand side:

Here  denotes the empty string. The projection of a string is essentially the same as a projection in relational algebra.

denotes the empty string. The projection of a string is essentially the same as a projection in relational algebra.

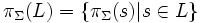

String projection may be promoted to the projection of a language. Given a formal language L, its projection is given by

Right quotient

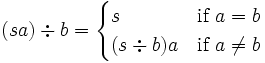

The right quotient of a letter a from a string s is the truncation of the letter a in the string s, from the right hand side. It is denoted as  . If the string does not have a on the right hand side, the result is the empty string. Thus:

. If the string does not have a on the right hand side, the result is the empty string. Thus:

The quotient of the empty string may be taken:

Similarly, given a subset  of a monoid

of a monoid  , one may define the quotient subset as

, one may define the quotient subset as

Left quotients may be defined similarly, with operations taking place on the left of a string.

Syntactic relation

The right quotient of a subset  of a monoid

of a monoid  defines an equivalence relation, called the right syntactic relation of S. It is given by

defines an equivalence relation, called the right syntactic relation of S. It is given by

The relation is clearly of finite index (has a finite number of equivalence classes) if and only if the family right quotients is finite; that is, if

is finite. In this case, S is a recognizable language, that is, a language that can be recognized by a finite state automaton. This is discussed in greater detail in the article on syntactic monoids.

Right cancellation

The right cancellation of a letter a from a string s is the removal of the first occurrence of the letter a in the string s, starting from the right hand side. It is denoted as  and is recursively defined as

and is recursively defined as

The empty string is always cancellable:

Clearly, right cancellation and projection commute:

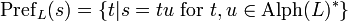

Prefixes

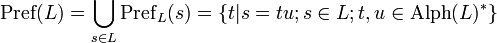

The prefixes of a string is the set of all prefixes to a string, with respect to a given language:

here  .

.

The prefix closure of a language is

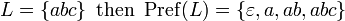

Example:

A language is called prefix closed if  .

.

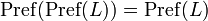

The prefix closure operator is idempotent:

The prefix relation is a binary relation  such that

such that  if and only if

if and only if  . This relation is a particular example of a prefix order.

. This relation is a particular example of a prefix order.

See also

References

- Hopcroft, John E.; Ullman, Jeffrey D. (1979). Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages and Computation. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing. ISBN 0-201-02988-X. Zbl 0426.68001. (See chapter 3.)