Stress functions

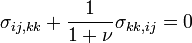

In linear elasticity, the equations describing the deformation of an elastic body subject only to surface forces on the boundary are (using index notation) the equilibrium equation:

where  is the stress tensor, and the Beltrami-Michell compatibility equations:

is the stress tensor, and the Beltrami-Michell compatibility equations:

A general solution of these equations may be expressed in terms the Beltrami stress tensor. Stress functions are derived as special cases of this Beltrami stress tensor which, although less general, sometimes will yield a more tractable method of solution for the elastic equations.

Beltrami stress functions

It can be shown [1] that a complete solution to the equilibrium equations may be written as

Using index notation:

Engineering notation

where  is an arbitrary second-rank tensor field that is continuously differentiable at least four times, and is known as the Beltrami stress tensor.[1] Its components are known as Beltrami stress functions.

is an arbitrary second-rank tensor field that is continuously differentiable at least four times, and is known as the Beltrami stress tensor.[1] Its components are known as Beltrami stress functions.  is the Levi-Civita pseudotensor, with all values equal to zero except those in which the indices are not repeated. For a set of non-repeating indices the component value will be +1 for even permutations of the indices, and -1 for odd permutations. And

is the Levi-Civita pseudotensor, with all values equal to zero except those in which the indices are not repeated. For a set of non-repeating indices the component value will be +1 for even permutations of the indices, and -1 for odd permutations. And  is the Nabla operator

is the Nabla operator

Maxwell stress functions

The Maxwell stress functions are defined by assuming that the Beltrami stress tensor  tensor is restricted to be of the form.[2]

tensor is restricted to be of the form.[2]

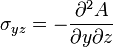

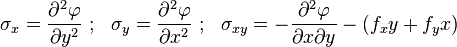

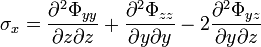

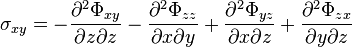

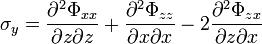

The stress tensor which automatically obeys the equilibrium equation may now be written as:[2]

The solution to the elastostatic problem now consists of finding the three stress functions which give a stress tensor which obeys the Beltrami–Michell compatibility equations for stress. Substituting the expressions for the stress into the Beltrami-Michell equations yields the expression of the elastostatic problem in terms of the stress functions:[3]

These must also yield a stress tensor which obeys the specified boundary conditions.

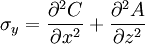

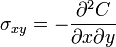

Airy stress function

The Airy stress function is a special case of the Maxwell stress functions, in which it is assumed that A=B=0 and C is a function of x and y only.[2] This stress function can therefore be used only for two-dimensional problems. In the elasticity literature, the stress function  is usually represented by

is usually represented by  and the stresses are expressed as

and the stresses are expressed as

Where  and

and  are values of of body forces in relevant direction.

are values of of body forces in relevant direction.

In polar coordinates the expressions are:

Morera stress functions

The Morera stress functions are defined by assuming that the Beltrami stress tensor  tensor is restricted to be of the form [2]

tensor is restricted to be of the form [2]

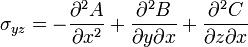

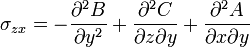

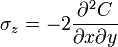

The solution to the elastostatic problem now consists of finding the three stress functions which give a stress tensor which obeys the Beltrami-Michell compatibility equations. Substituting the expressions for the stress into the Beltrami-Michell equations yields the expression of the elastostatic problem in terms of the stress functions:[4]

Prandtl stress function

The Prandtl stress function is a special case of the Morera stress functions, in which it is assumed that A=B=0 and C is a function of x and y only.[4]In Saint Venant’s theory of torsion for non-circular sections, the displacements are given by uz = yφ(x) uy = −zφ (x) ux = dφ dx ψ (y,z) (1) If dφ / dx =φ ′ is a constant, then the only non-zero stresses are σ xz = G ∂ux ∂z + ∂uz ∂x ⎛ ⎝ ⎜ ⎞ ⎠ ⎟ = G ∂ux ∂z +φ ′y ⎛ ⎝ ⎜ ⎞ ⎠ ⎟ σ xy = G ∂ux ∂y + ∂uy ∂x ⎛ ⎝ ⎜ ⎞ ⎠ ⎟ = G ∂ux ∂y −φ ′z ⎛ ⎝ ⎜ ⎞ ⎠ ⎟ (2) and all the equilibrium equations are satisfied if ∂σ xy ∂y + ∂σ xz ∂z = 0 (3) This equation can be satisfied automatically by writing the stresses in terms of a function, Φ , called the Prandtl stress function, where σ xy = ∂Φ ∂z , σ xz = − ∂Φ ∂y (4) However, from Eq. (2), we have G ∂ux ∂z = − ∂Φ ∂y − Gφ ′ y G ∂ux ∂y = ∂Φ ∂z + Gφ ′ z which also implies EM 424: Prandtl Stress Function 16 G ∂2ux ∂z∂y = − ∂2Φ ∂y2 − Gφ ′ G ∂2ux ∂y∂z = ∂2Φ ∂z2 + Gφ ′ However, these mixed derivatives of the displacement ux must be equal, if we are to be able to integrate the strains to find this displacement, and this compatibility condition requires that the stress function satisfy ∂2Φ ∂y2 + ∂2Φ ∂z 2 = −2Gφ ′ (5) or, equivalently, ∇2Φ = −2Gφ ′ (6) which is called Poisson’s equation. We know that on the outer boundary of the bar we have no applied tractions so that Tx (n) =σ xyny +σ xznz = 0 (7) and y and z components of the traction vector are identically zero, so that in terms of the Prandtl stress function we have ∂Φ ∂z ny − ∂Φ ∂z nz = 0 (8) But by examining a small element near the surface (Fig.1), we see that Eq. (8) also implies that ∂Φ ∂z dz ds + ∂Φ ∂y dy ds = 0 (9)

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sadd, Martin H. Elasticity: Theory, Applications, and Numerics. Elsevier Science & Technology Books. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-12-605811-6.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Sadd, M. H. (2005) Elasticity: Theory, Applications, and Numerics, Elsevier, p. 364

- ↑ Knops (1958) p327

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sadd, M. H. (2005) Elasticity: Theory, Applications, and Numerics, Elsevier, p. 365

References

- Sadd, Martin H. (2005). Elasticity - Theory, applications and numerics. New York: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-12-605811-3. OCLC 162576656.

- Knops, R. J. (1958). "On the Variation of Poisson's Ratio in the Solution of Elastic Problems". The Quarterly Journal of Mechanics and Applied Mathematics (Oxford University Press) 11 (3): 326–350. doi:10.1093/qjmam/11.3.326.

See also

- Elasticity (physics)

- Elastic modulus

- Infinitesimal strain theory

- Linear elasticity

- Solid mechanics

- Stress (mechanics)