Storm chasing

Storm chasing is broadly defined as the pursuit of any severe weather condition, regardless of motive, which can be curiosity, adventure, scientific exploration, or for news professions/media coverage.[1]

A person who chases storms is known as a storm chaser, or simply a chaser. While witnessing a tornado is the single biggest objective for most chasers, many chase thunderstorms and delight in seeing cumulonimbus cloud structure, watching a barrage of hail and lightning, and seeing what skyscapes unfold. There are also a smaller number of storm chasers who chase hurricanes.

Nature of and motivations for chasing

Storm chasing is chiefly a recreational endeavor, with motives usually given toward photographing the storm and for multivariate personal reasons.[2] These can include the beauty of views afforded by the sky and land, intangible experiences such as feeling one with a much larger and powerful natural world,[3] the challenge of correctly forecasting and intercepting storms with the optimal vantage points,[4] and pure thrill seeking.[5] Pecuniary interests and competition may also be components; in contrast, camaraderie is common.

Although scientific work is sometimes cited as a goal, direct participation in such work is almost always impractical except for those collaborating in an organized university or government project.[6] Many chasers also are storm spotters, reporting their observations of hazardous weather to the authorities. These reports greatly benefit real-time warnings with ground truth reports as well as science by increasing the reliability of severe storm databases used in climatology and other research.[7] Additionally, many recreational chasers submit photos and videos to researchers as well as to the National Weather Service (NWS) for spotter training.[8]

Storm chasers are not generally paid to chase, with the exception of television media crews in certain television markets, video stringers and photographers, and researchers such as a handful of graduate meteorologists and professors. An increasing number do sell storm videos and pictures and manage to make a profit. A few operate "chase tour" services, making storm chasing a recently developed niche tourism.[9][10] Financial returns usually are relatively meager given the expenses with most chasers spending more than they take in and very few making a living solely from chasing.

No degree or certification is required to be a storm chaser. The National Weather Service does conduct severe weather workshops oriented toward operational meteorologists and, usually early in the spring, holds storm spotter training classes.[11]

History

The first recognized storm chaser is David Hoadley (1938– ), who began chasing North Dakota storms in 1956; systematically using data from area weather offices. He is widely considered the pioneer storm chaser[12] and was the founder of Storm Track magazine.

Bringing research chasing to the forefront was Neil B. Ward (1914-1972) who in the 1950s and 1960s enlisted the help of Oklahoma Highway Patrol to study storms. His work pioneered modern storm spotting and made institutional chasing a reality.

In 1972, the University of Oklahoma in cooperation with the National Severe Storms Laboratory began the Tornado Intercept Project, with the first outing taking place on April 19 of that year.[13] This was the first large-scale chase activity sponsored by an institution. It culminated in a brilliant success in 1973, with the Union City, Oklahoma tornado providing a foundation for tornado and supercell morphology.[14] The project produced the first legion of veteran storm chasers, with Hoadley's Storm Track magazine bringing the community together in 1977.

Storm chasing then reached popular culture in three major spurts: in 1978 with the broadcast of a segment on the television program In Search of...; in 1985 with a documentary on the PBS series Nova; and in May 1996 with the theatrical release of Twister which provided an action-packed but distorted glimpse at the hobby. Further early exposure to storm chasing encouraging some in the weather community resulted from several articles beginning in the late 1970s in Weatherwise magazine.

Various television programs and increased coverage of severe weather by the media, especially since the initial video revolution in which VHS ownership became widespread by the early 1990s, substantially elevated awareness of and interest in storm chasing. The advent of the Internet, in particular, contributed to a significant growth in number of storm chasers since the mid-late 1990s. A sharp increase in the general public impulsively wandering in their local area searching for tornadoes similarly is largely attributable to these factors. The 2007-2011 Discovery Channel reality series Storm Chasers produced another surge in activity.

From their advent in the 1970s until the mid-1990s, scientific field projects were occasionally conducted during spring in the Great Plains.[14] Then, the first of the seminal VORTEX projects occurred in 1994-95[15] and this was soon followed by field experiments each spring, with another large project, VORTEX2, in 2009-10.[16]

Typical storm chase

Chasing often involves driving thousands of miles in order to witness the relatively short window of time of active severe thunderstorms. It is not uncommon for a storm chaser to end up empty handed on any particular day. Storm chasers' degrees of involvement, competencies, philosophies, and techniques vary widely, but many chasers spend a significant amount of time forecasting; both before going on the road as well as during the chase, using a variety of sources for weather data. Most storm chasers are not meteorologists, and many chasers expend significant time and effort in learning meteorology and the intricacies of severe convective storm prediction through both study and experience.[17]

Most chasing is accomplished by driving, however, a few individuals occasionally fly planes and television stations in some markets use helicopters. Research projects sometimes employ aircraft, as well.

Dangers

There are inherent dangers involved in pursuing hazardous weather. These range from lightning, tornadoes, large hail, flooding, hazardous road conditions (rain or hail-covered roadways), animals on the roadway, downed power lines (and occasionally other debris), reduced visibility from heavy rain (often wind blown), blowing dust, and hail fog. Most directly weather related hazards such as from a tornado are minimized if the storm chaser is knowledgeable and cautious. In some situations, severe downburst winds may push automobiles around, especially high profile vehicles. Tornadoes affect a relatively small area and are predictable enough to be avoided if a safe distance is maintained and chasers avoid placement in the direction of travel of a tornado (in most cases to the north and to the east of a tornado). Lightning, however, is an unavoidable hazard. "Core punching", storm chaser slang for driving through a heavy precipitation core to intercept the area of interest within a storm, is recognized as hazardous due to reduced visibility and because many tornadoes are rain-wrapped. The "bear's cage" refers to the area under a rotating wall cloud, which is the "bear", and to the blinding precipitation (which can include window-shatteringly large hail) surrounding some or all sides of a tornado, which is the "cage". Similarly, chasing at night heightens risk due to darkness.[18]

In reality, the most significant hazard is driving,[18][19] which is made more dangerous by the severe weather. Adding still more to this hazard are the multiple distractions which can compete for a chaser's attention, such as driving, communicating with chase partners and others with a phone and/or radio, navigating, watching the sky, checking weather data, and shooting photos or video. Again here, prudence is key to minimizing the risk. Chasers ideally work to prevent the driver from multitasking either by chase partners covering the other aspects or by the driver pulling over to do these other things if he/she is chasing alone. Falling asleep while driving is a chase hazard, especially on long trips back. This also is exacerbated by nocturnal darkness and by the defatigating demands of driving through precipitation and on slick roads.[17][20]

Incidents

For nearly 60 years, the only known chaser deaths were driving related. The first was Christopher Phillips, a University of Oklahoma undergraduate student, killed in a hydroplaning accident when swerving to miss a rabbit in 1984,[21] and the two other incidents occurred when Jeff Wear was driving home from a hurricane chase in 2005[22] and when Fabian Guerra swerved to miss a deer while driving to a chase in 2009.[23] On May 31, 2013, an extreme weather event led to the first known chaser deaths inflicted directly by weather when the widest tornado ever recorded struck near El Reno, Oklahoma. Engineer Tim Samaras, his photographer son Paul, and meteorologist Carl Young were killed doing infrasonic field research by an exceptional combination of events in which an already large tornado swelled within less than a minute to 2.6 miles (4.2 km) wide simultaneously as it unexpectedly changed direction and it was obscured in heavy precipitation during most of its life cycle.[24] Several other chasers were also struck and injured by this tornado and its parent supercell's rear flank downdraft.[25] There are other incidents in which chasers were injured by automobile accidents, lightning strikes, and tornado impacts.[citation needed]

Geographical, seasonal, and diurnal activity

Storm chasers are most active in the spring and early summer, particularly May and June, across the Great Plains of the United States (extending into Canada) in an area colloquially known as Tornado Alley, with many hundred individuals active on some days during this period. This coincides with the most consistent tornado days[26] in the most desirable topography of the Great Plains. Not only are the most intense supercells common here, but because of the moisture profile of the atmosphere, the storms tend to be more visible than locations farther east where there are also frequent severe thunderstorms. There is a tendency for chases earlier in the year to be farther south, shifting farther north with the jet stream as the season progresses. Storms occurring later in the year tend to be more isolated and slower moving, both of which are also desirable to chasers.[17] Advancing technology since the mid-2000s led to chasers more commonly targeting less amenable areas (i.e. hilly or forested) that were previously eschewed when continuous wide visibility was critical. These advancements, primarily in-vehicle weather data such as radar, also lead to an increase in chasing after nightfall.

Chasers may operate whenever significant thunderstorm activity is occurring; whatever the date. This most commonly includes more sporadic activity occurring in warmer months of the year bounding the spring maximum, such as the active month of April; and farther north especially, the summer months. An annually inconsistent and substantially smaller peak of severe thunderstorm and tornado activity also arises in the transitional months of autumn, particularly October and November. In the area with the most consistent significant tornado activity, the Southern Plains, the tornado season is intense but relatively brief.

Some organized chasing efforts have also begun in the Top End of the Northern Territory and in southeast Australia,[27][28] with the biggest successes in November and December. A handful of individuals are also known to be chasing in other countries, including Israel, Italy, Spain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Finland, Germany, Switzerland, Bulgaria, Estonia, Argentina, and New Zealand; although many people trek to the Great Plains of North America from these and other countries around the world (especially from the United Kingdom).

Equipment

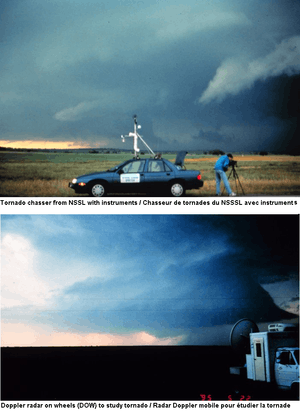

Most storm chasers will vary with regards to the amount of equipment used, some prefer a minimalist approach; for example, where only basic photographic equipment is taken on a chase, while others use everything from satellite based tracking systems and live data feeds to vehicle mounted weather stations and hail guards.

Historic

Historically, storm chasing relied on either in field analysis or in some cases nowcasts from trained observers and forecasters. The first in-field technology consisted of radio gear for communication. Much of this equipment could also be adapted to receive radiofax data which was useful for receiving basic observational and analysis data. The primary users of such technology were university or government research groups who often had larger budgets than individual chasers.

Radio scanners were also heavily used to listen in on emergency services and storm spotters so as to determine where the most active or dangerous weather was located. A number of chasers were also radio amateurs, and used mobile (or portable) amateur radio to communicate directly with spotters and other chasers, allowing them to keep abreast of what they could not themselves see.

It was not until the mid to late 1980s that the evolution of the laptop computer would begin to revolutionize storm chasing. Early on, some chasers carried acoustic couplers to download batches of raw surface and upper air data from payphones. The technology was too slow for graphical imagery such as radar and satellite data; and during the first years this wasn't available on any connection over telephone lines, anyway. Some raw data could be downloaded and plotted by software, such as surface weather observations using WeatherGraphix (predecessor to Digital Atmosphere) and similar software or for upper air soundings using SHARP, RAOB, and similar software.

Most meteorological data was acquired all at once early in the morning, and the rest of day's chasing was based on analysis and forecast gleaned from this; as well as on visual clues that presented themselves in the field throughout the day. Plotted weather maps were often analyzed by hand for manual diagnosis of meteorological patterns. Occasionally chasers would make stops at rural airstrips or NWS offices for an update on weather conditions. NOAA Weather Radio could provide information in the vehicle, without stopping, such as weather watches and warnings, surface weather conditions, convective outlooks, and NWS radar summaries. Nowadays, storm chasers may use high-speed Internet access available in any library, even in small towns in the US. This data is available throughout the day, but one must find and stop at a location offering Internet access.

With the development of the mobile computers, the first computer mapping software became feasible, at about the same time the VHS camcorder began to grow in popularity rapidly. Prior to the mid to late 1980s most motion picture equipment consisted of 8 mm film cameras. While the quality of the first VHS consumer cameras was quite poor (and the size somewhat cumbersome) when compared to traditional film formats, the amount of video which could be shot with a minimal amount of resources was much greater than any film format at the time.

In the 1980s and 1990s, The Weather Channel and A.M. Weather were popular with chasers, in the morning preceding a chase for the latter and both before and during a chase for the former. Commercial radio sometimes also provides weather and damage information. The 1990s brought technological leaps and bounds. With the swift development of solid state technology, television sets for example could be installed with ease in most vehicles allowing storm chasers to actively view local TV stations. Mobile phones became popular making group coordination easier when traditional radio communications methods were not ideal. The development of the public Internet in 1993 allowed FTP access to some of the first university weather sites.

The mid-1990s marked the development of smaller more efficient marine radars. While such marine radars are illegal if used in land-mobile situations, a number of chasers were quick to adopt them in an effort to have mobile radar.[29] These radars have been found to interfere with research radars, such as the Doppler On Wheels utilized in field projects. The first personal lightning detection and mapping devices also became available[30] and the first online radar data was offered by private corporations or, at first with delays, with free services. A popular data vendor by the end of the 1990s was WeatherTAP.

Current

Chasers used paper maps for navigation and some of those now using GPS still use these as a backup or for strategizing with other chasers. Foldable state maps can be used but are cumbersome due to the multitude of states needed and only show major roads. National atlases allow more detail and all states are contained in a single book, with AAA favored and Rand McNally followed by Michelin also used. The preferred atlases due to great detail in rural areas are the "Roads of..." series originally by Shearer Publishing, which first included Texas but expanded to other states such as Oklahoma and Colorado. Covering every state of the union are the DeLorme "Atlas and Gazetteer" series. DeLorme also produced early GPS receivers that connected to laptops and continues to be one of two major mapping software creators. DeLorme Street Atlas USA or Microsoft Streets & Trips are used by most chasers.

A major turning point was the advent of civilian GPS in 1996. At first, GPS units were very costly and only offered basic functions, but that would soon change. Towards the late 1990s the Internet was awash in weather data and free weather software, the first true cellular Internet modems for consumer use also emerged providing chasers access to data in the field without having to rely on a nowcaster. The NWS also released the first free, up to date NEXRAD Level 3 radar data. In conjunction with all of this, GPS units now had the ability to connect with computers, allowing greater ease when navigating.

2001 marked the next great technological leap for storm chasers as the first Wi-Fi units began to emerge offering wireless broadband service in many cases for free. Some places (restaurants, motels, libraries, etc.) were known to reliably offer wireless access and wardriving located other availabilities. In 2002 the first Windows-based package to combine GPS positioning and Doppler radar appeared called SWIFT WX.[31] SWIFT WX allowed storm chasers to position themselves accurately relative to tornadic storms while mobile.

In 2004 two more storm chaser tools emerged. The first was a new XM Satellite Radio based system[32] utilizing a special receiver and Baron Services weather software. Unlike preexisting cellular based services there was no risk of dead spots, and that meant that even in the most remote areas storm chasers still had a live data feed. The second tool was a new piece of software called GRLevel3.[33] GRLevel3 utilized both free and subscription based raw weather radar files, displaying the data in a true vector format with GIS layering abilities. Since 2006 a growing number of chasers are using Spotter Network, which uses GPS data to plot real time position of chasers and spotters, and allows observers to report significant weather as well as GIS layering for navigation maps, weather products, and the like.

The most common chaser communications device is the cellular phone. These are used for both voice and data connections. External antennas and amplifiers may be used. It is not uncommon that chasers travel in small groups of cars, and may use CB radio (declining in use) or inexpensive GMRS / FRS hand-held transceivers for inter-vehicle communication. More commonly, many chasers are also ham radio operators and use the 2 meters VHF and, less often, 70 cm UHF bands to communicate between vehicles or with Skywarn / Canwarn spotter networks. Scanners are often used to monitor spotter, sometimes public safety communications, and can double as weather radios. Since the mid-2000s, social networking services may also be used, with Twitter most used for ongoing events, Facebook for sharing images and discussing chase reports, and Google+ trailing in adoption. Social networking services largely replace forums and email lists (which complemented and eventually supplanted Stormtrack magazine) for conversing about storms.

In-field environmental data is still popular among some storm chasers, especially temperature, moisture, and wind speed and direction data. Many have chosen to mount weather stations atop their vehicles. Others use handheld anemometers. Rulers or baseballs may be brought along for measuring hail and for showing as a comparison object.

Chasers heavily utilize still photography since the beginning. Videography gained prominence by the 1990s into the early 2000s but a resurgence of photography occurred with the advent of affordable and versatile digital SLR cameras. Prior to this, 35 mm print and slide film formats were mostly used, along with some medium format cameras. In the late 2000s, mobile phone 3G data networks became fast enough to allow live streaming video from chasers using webcams. This live imagery is frequently used by the media, as well as NWS meteorologists, emergency managers, and the general public for direct ground truth information, and it provides video sales opportunities to chasers. Also by this time, camcorders using memory cards to record video began to be adopted. Digital video had been around for years but was recorded on tape, whereas solid-state is random access rather than sequential access (linear) and has no moving parts. Late in the 2000s HD video began to overtake SD (which had been NTSC in North America) in usage as prices came down and performance increased (initially there were low-light and sporadic aliasing problems due to chip and sensor limitations).

Late in the 2000s smartphones increased in usage, with radar viewing applications frequently used. Particularly, RadarScope on the iOS platform and Pkyl3 on Android are favored. Other apps may be used as are browsers for viewing meteorological data and interacting with social networking services. Some handsets can be used as WiFi hotspots and wireless cards may also be used to avoid committing a handset to tethering or operating as a hotspot. Some hotspots operate as mobile broadband MNVO devices using any radio spectrum that is both available and is in contract with a service provider. Such devices may expand mobile data range beyond a single carrier's service area and typically can work on month-to-month contracts. Adoption of tablet computers is expanding as of the early 2010s. 4G LTE has been adopted when available and can be especially useful for uploading HD video.

Ethics

A growing number of experienced storm chasers advocate the adoption of a code of ethics in storm chasing featuring safety, courtesy, and objectivity as the backbone.[19][34] Storm chasing is a highly visible recreational activity (which is also associated with science) that is vulnerable to sensationalist media promotion.[35] Veteran storm chasers Chuck Doswell and Roger Edwards have deemed reckless storm chasers as "yahoos".[36] Doswell and Edwards believe poor chasing ethics at TV news stations add to the growth of "yahoo" storm chasing.[37] Edwards and Rich Thompson, among others, also expressed concern about pernicious effects of media profiteering[38] with Matt Crowther, among others, agreeing in principle but viewing sales as not inherently corrupting.[39] Self-policing is seen as the means to mold the hobby. There is occasional discussion among chasers that at some point regulation may be adopted due to increasing numbers of chasers and poor behavior by some individuals; however, many chasers do not expect this eventuality and almost all oppose regulations—as do some formal studies of dangerous leisure activities which advocate deliberative self-policing.[40]

As there is for storm chaser conduct, there is concern about chaser responsibility. Since some chasers are trained in first aid and even first responder procedures, it is not uncommon for tornado chasers to be first on a scene, tending to storm victims or treating injuries at the site of a disaster in advance of emergency personnel and other outside aid.[41] Jason Persoff, M.D., a physician and storm chaser, ended his chase to treat victims of the 2011 Joplin tornado and has provided first response and mass-casualty incident triage suggestions to chasers.[42]

In popular culture

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Storm chasing. |

References

- ↑ Glickman, Todd S. (ed.) (2000). Glossary of Meteorology (2nd ed.). American Meteorological Society. ISBN 978-1-878220-34-9.

- ↑ The thrill of the chase, the fury of the storm USA Today

- ↑ Hoadley, David (Mar 1982). "Commentary: Why Chase Tornadoes?". Storm Track 5 (3): 1.

- ↑ Marshall, Tim (Apr-May 1993). "A Passion for Prediction: There's more to chasing than intercepting a tornado". Weatherwise 46 (2): 22–6. doi:10.1080/00431672.1993.9930229.

- ↑ Clary, Mike (1983). "The Thrill of Confrontation… Chasing Tornadoes". Weatherwise 39 (3): 136–45. doi:10.1080/00431672.1986.9927045.

- ↑ Robertson, David (Oct 1999). "Beyond Twister: A Geography of Recreational Storm Chasing on the Southern Plains". Geographical Review 89 (4): 533–53. doi:10.2307/216101. JSTOR 216101.

- ↑ Edwards, Roger (Mar-Apr 1994). "What You See Really Does Matter". Storm Track 17 (3): 10–11.

- ↑ Doswell III, Charles A.; A.R. Moller, H.E. Brooks (Aug 1999). "Storm Spotting and Public Awareness since the First Tornado Forecasts of 1948". Wea. Forecasting 14 (4): 544–57. Bibcode:1999WtFor..14..544D. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1999)014<0544:SSAPAS>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Cantillon, Heather; R.S. Bristow (2001). "Tornado chasing: an introduction to risk tourism opportunities". Proc. 2000 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium. Newtown Square, PA: U.S.D.A., Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station. Gen. Tech. Rep. NE-276.

- ↑ Xu, Shuangyu; C. Barbieri, S.W. Stanis, P.S. Market. "Sensation-Seeking Attributes Associated with Storm-Chasing Tourists: Implications for Future Engagement". International Journal of Tourism Research. doi:10.1002/jtr.860.

- ↑ "NWS Skywarn". National Weather Service. 2011-05-10. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- ↑ Who were the first storm chasers? Stormtrack

- ↑ Grazulis, Thomas P. (2001). The Tornado: Nature's Ultimate Windstorm. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3258-2.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Bluestein, Howard (August 1999). "A History of Severe-Storm-Intercept Field Programs". Wea. Forecasting 14 (4): 558–77. Bibcode:1999WtFor..14..558B. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1999)014<0558:AHOSSI>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Erik N.; J. M. Straka, R. Davies-Jones, C. A. Doswell, F. H. Carr, M. D. Eilts, D. R. MacGorman (1994). "Verification of the Origins of Rotation in Tornadoes Experiment: VORTEX". Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 75 (6): 995–1006. Bibcode:1994BAMS...75..995R. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1994)075<0995:VOTOOR>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Wurman, Joshua; D. Dowell, Y. Richardson, P. Markowski, E. Rasmussen, D. Burgess, L. Wicker, H. B. Bluestein (2012). "The Second Verification of the Origins of Rotation in Tornadoes Experiment: VORTEX2". B. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93 (8): 1147–70. Bibcode:2012BAMS...93.1147W. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00010.1.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Vasquez, Tim (2008). Storm Chasing Handbook (2nd ed.). Garland, TX: Weather Graphics Technologies. ISBN 0-9706840-8-8.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Marshall, Tim; David Hoadley (illustrator) (May 1995). Storm Talk.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Doswell III, Charles A. (4 April 2009). "Storm Chasing with Safety, Courtesy, and Responsibility". Michael Graff. Archived from the original on 21 January 2009. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ↑ Marshall, Tim; David Hoadley (illustrator) (1998). Storm Chase Manual (4th ed.). Texas.

- ↑ "'It Sounded Like a Freight Train': The Dangers of Storm Chasing". AccuWeather. May 24, 2010. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ↑ Jeff Wear

- ↑ Fabian Guerra

- ↑ Davies, Jon (Jun 4, 2013). "The El Reno tornado - unusual & very deadly". Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ↑ Masters, Jeff (Jun 2, 2013). "Tornado Scientist Tim Samaras and Team Killed in Friday's El Reno, OK Tornado". Weather Underground. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ↑ Brooks, Harold; P.R. Concannon, C.A. Doswell (2003-08-29). "Severe Thunderstorm Climatology". National Severe Storms Laboratory. Retrieved 2012-02-27.

- ↑ McLaughlin, Murray (2003-12-17). "Storm chasers hit Top End". Australian Broadcasting Corporation (7.30 Report). Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- ↑ Krien, Anna (2004-07-04). "Weather from hell is heaven on earth for storm troops". Fairfax Digital (The Age). Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- ↑ Portable Radar For Chasers

- ↑ Boltek.com

- ↑ Swiftwx.com

- ↑ WxWorx.com

- ↑ GRLevelX.com

- ↑ Moller, Alan (Mar 1992). "Storm Chase Ethics". Storm Track 15 (3): 8–9.

- ↑ The Online Storm Chasing FAQ

- ↑ Edwards, Roger (7 February 2002). "The Reality of Storm Chase Yahoos". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ↑ Edwards, Roger; Doswell, Chuck. "Irresponsible Media Storm Chase Practices". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ↑ Rich Thompson; Roger Edwards. "Cancer Within". Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ Crowther, Matt. "Some Chase Musings". Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ Olivier, Steve (2006). "Moral Dilemmas of Participation in Dangerous Leisure Activities". Leisure Studies 25 (1): 95–109. doi:10.1080/02614360500284692.

- ↑ Burgess, Cindy. "The Weather Network". 2011.

- ↑ Persoff, Jason (5 June 2011). "First Response Mode: May 22, 2011, Joplin Tornado". Blogger. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

External links

- The Meaning of Chasing (T.J. Turnage)

- National Storm Chaser Convention

- Storm Spotters Guides: Chasing

- Beginners guide to storm chasing