Stepan Shahumyan

| Stepan Shahumyan | |

|---|---|

| |

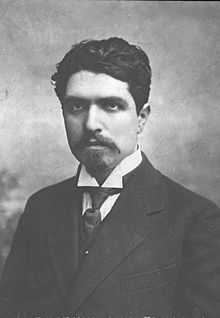

| Soviet leader Stepan Shahumyan | |

| Commissar Extraordinary for the Caucasus | |

| In office 25 April 1918 – 31 July 1918 | |

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 October 1878 Tiflis, Tiflis Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 20 September 1918 (aged 39) Krasnovodsk, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Resting place | Unknown |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Alma mater | Humboldt University of Berlin |

| Occupation | Politician, revolutionary |

Stepan Shahumyan (Armenian: Ստեփան Շահումյան; Russian: Степан Георгиевич Шаумян, Stepan Georgevich Shaumyan; 1 October 1878 – 20 September 1918) was a Bolshevist Russian Communist politician and revolutionary active throughout the Caucasus.[1] Shahumyan was an ethnic Armenian and his role as a leader of the Russian revolution in the Caucasus earned him the nickname of the "Caucasian Lenin", a reference to the leader of the Russian Revolution, Vladimir Lenin.[2]

Although the founder and editor of several newspapers and journals, Shahumyan is best known as the head of the Baku Commune, a short lived committee appointed by Lenin in March 1918 with the enormous task of leading the revolution in the Caucasus and West Asia. His tenure as leader of the Baku Commune was marred with numerous problems including ethnic violence between Baku’s Armenian and Azerbaijani populations, attempting to defend the city against an advancing Turkish army, all the while attempting to spread the cause of the revolution throughout the region. Unlike many of the other Bolsheviks at the time however, he preferred to resolve many of the conflicts he faced peacefully, rather than with force and terror.[3]

He was known by various aliases, including "Suren", "Surenin" and “Ayaks".[1] As the Baku Commune was voted out of power in July 1918, Shahumyan and his followers, known as the twenty six Baku Commissars abandoned the city, fleeing across the Caspian Sea. However, he and the rest of the Commissars were captured and executed by anti-Bolshevik forces on 20 September 1918. [citation needed]

Early life

Stepan Gevorgi (later Georgevich) Shahumyan was born in Tiflis, Georgia, then part of the Russian Empire, to a family of a cloth merchant. He studied at the Saint Petersburg Polytechnical University and the Riga Technical University, where he joined the Russian Social Democratic Party in the 1900. In 1905 he graduated from the philosophy department of Humboldt University of Berlin. [citation needed]

Revolutionary beginnings

He was arrested by the Tsarist government for taking part in student political activities on campus, and exiled back to Transcaucasia. Shahumyan made his way to German soil, where he met with such exiles from the Russian Empire as Lenin, Julius Martov and Georgi Plekhanov. Upon returning to Transcaucasia, he became a teacher, and the leader of local Social Democrats in Tiflis, as well as a prolific writer of Marxist literature. At the 1903 Congress, he sided with the Bolsheviks. By 1907 he had moved to Baku to head up the significant Bolshevik movement in the city. In 1914, he led the general strike in the city. The strike was crushed by Imperial Army and Shahumyan was arrested and sent to prison. He escaped just as the February Revolution of 1917 was beginning. [citation needed]

The Baku Commune

Early problems

Following the October Revolution (which was centered in Saint Petersburg/Petrograd and Moscow, and thus had little effect on Baku), Shaumyan was made Commissar Extraordinary for the Caucasus and Chairman of the Baku Council of People's Commissars. The government of the Baku Commune consisted of an alliance of Bolsheviks, Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and Dashnaks.

In March 1918 the leaders of Baku Commune disarmed a group of Azerbaijani soldiers, who came to Baku from Lenkoran on the ship called Evelina to attend the funeral of Mamed Taghiyev, son of the millionaire Zeynalabdin Taghiyev.[4] In response, a huge crowd gathered in the yard of one of the Baku mosques and adopted a resolution demanding the release of the rifles confiscated by the Soviet from the crew of the Evelina. The Azerbaijani Bolshevik organization Hümmet attempted to mediate the dispute by proposing that the arms taken from the Savage Division are transferred to the custody of the Hümmet. Shahumyan agreed to this proposal. But on the afternoon of March 31, when Muslim representatives appeared before the Baku Soviet leadership to take the arms, shots were already heard in the city and the Soviet commissar Prokofy Dzhaparidze refused to provide arms and informed the Hümmet leadership that "Musavat had launched a political war".[5] While it was not established who fired the first shot, the Baku commune leaders accused the Muslims of starting the hostilities, and with the support of Dashnak forces attacked the Muslim quarters. Later Shahumyan admitted that the Bolsheviks deliberately used a pretext to attack their political opponents:

We needed to give a rebuff, and we exploited the opportunity of the first attempt at an armed assault on our cavalry unit and began an attack on the whole front. Due to the efforts of both the local Soviet and the Military-revolutionary committee of the Caucasus Army, which moved here (from Tiflis and Sarikamish) we already had armed forces - about 6,000 strong. Dashnaktsutiun also had 3,000 - 4,000 of national forces, which were at our disposal. The participation of the latter lent the civil war, to some extent, the character of an ethnic massacre, however, it was impossible to avoid this. We were going for it deliberately. The Muslim poor suffered severely, however they are now rallying around the Bolsheviks and the Soviet.[6]

On the morning of April 1, 1918, the Committee of Revolutionary Defense of Baku's Soviet issued a leaflet which said:

In view of the fact that the counterrevolutionary Musavat party declared war on the Soviet of Workers', Soldiers', and Sailors' Deputies in the city of Baku and thus threatened the existence of the government of the revolutionary democracy, Baku is declared to be in a state of siege[7]

Bolsheviks had only about 6,000 loyal troops, and they were forced to seek support from either Muslim Musavat or Armenian Dashnaktsutyun. Shahumyan, himself an Armenian, chose the latter.[8] Shahumyan considered the March events to be a triumph of the Soviet power in the Caucasus:

According to Firuz Kazemzadeh, the Soviet provoked March events to eliminate its most formidable rival – the Musavat. However, when Soviet leaders reached out to ARF for assistance against the Azerbaijani nationalists, the conflict degenerated into a massacre with the Armenians killing the Muslims irrespective of their political affiliations or social and economic position.[9][8] Estimates of the number of Azerbaijanis and other Muslims massacred in Baku and surrounding regions range between 3,000 and 12,000.[4]

The Baku Soviet's Committee of Revolutionary Defense issued a proclamation early in April 1918, which insisted on an anti-Soviet character of the rebellion and blamed Musavat and its leadership for the events. The Soviet's statement asserted that there was a carefully laid out plot by Musavat to overthrow the Baku Soviet and to establish its own regime:

The enemies of Soviet power in the city of Baku have raised their head. The malice and hatred with which they viewed the revolutionary organ of the workers and soldiers began recently to overflow into open counterrevolutionary activities. The appearance of the staff of the Savage Division, headed by the unmasked Talyshkhanov, the events in Lenkoran, in Mugan, and at Shemakha, the capture of Petrovsk by the Daghestan regiment and the withholding of grain shipments from Baku, the threats of Elisavetpol, and in the last few days of Tiflis, to march on Baku, against soviet power, the aggressive movements of the armored train of the Transcaucasian Commissariat in Adzhikabul, and, finally, the outrageous behavior of the Savage Division on the steamship Evelina in shooting comrades—all this speaks of the criminal plans of the counterrevolutionaries grouped mainly around the Bek party Musavat and having as its goal the overthrow of Soviet power." [7]

Less than six months later, in September 1918 Nuri Pasha's Ottoman-led Army of Islam, supported by local Azeri forces, recaptured Baku and subsequently killed an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 ethnic Armenians.[10][11]

The Bolsheviks clashed with Dashnaks and Mensheviks over the involvement of British forces, which the latter two welcomed. In either case, Shahumyan was under direct orders from Moscow to refuse aid offered by the British.[12] However, he understood the consequences of not accepting British aid, including a further massacre of Armenians by the Turks. Major Ranald MacDonell, a seasoned diplomat and the British vice-consul of Baku, was tasked by his superiors in attempting to persuade Shahumyan to revise his position.[13]

Coup plots

In mid-summer, MacDonell personally visited Shahumyan's home in Baku and the two discussed the issue of British military involvement in a generally amiable conversation. Shahumyan first raised the specter of what British involvement would entail: "Is your General Dunsterville [the head of the military force awaiting orders to enter Baku] coming to Baku to turn us out?" MacDonell reassured him that Dunsterville, being a member of the military, was not claiming any political stake in the conflict but was merely interested in helping him defend the city. Unconvinced, Shahumyan replied, "And you really believe that a British general and a Bolshevik commissar would make good partners....No! We will organise our own force to fight the Turk."[3]

Shahumyan was under the impression that the Bolsheviks would soon be sending reinforcements from the Caspian Sea to assist him although the prospects of receiving such relief remained unlikely. He had sent numerous telegrams to Moscow extolling the fighting abilities of his Armenian units but warned that they too, would soon be unable to halt the advance of Enver's army. With this, MacDonell's and Shahumyan's conversation ended with the possibility of accepting British aid in exchange for complete Bolshevik control over the military force, terms the British could not immediately accept.[3]

Relations between the Baku Commune and the British soon reached a turning point when Britain decided to reverse its support for Bolsheviks. Shahumyan's intransigence had cost him their support, as MacDonell was informed by a British officer on July 10: "the new policy of the British and French governments was to support the anti-Bolshevik forces....It mattered little whether they were Tsarist or Social Revolutionary."[3]

Over the last few days, numerous people had visited MacDonell, wpleading for a withdrawal of British support for Shahumyan. Many claimed to be former Tsarist officers offering their service to rise against the Bolsheviks although MacDonell reportedly suspected most to have actually been agents working on behalf of the Bolsheviks.[3]

Expulsion

On 26 July 1918, the Bolsheviks were outvoted 259-236 in the Baku Soviet. Shahumyan's support had eroded and many of his key supporters abandoned him. Angered with the outcome of the vote, he announced that his party would withdraw from the Soviet and Baku itself: "With pain in our hearts and curses on our lips, we who had come here to die for the Soviet regime are forced to leave."[3]

A new government headed primarily by Russians, known as Central Caspian Dictatorship (Diktatura Tsentrokaspiya) was formed, as British forces under General Lionel Dunsterville occupied Baku the same day. [citation needed]

Arrest and death

On 31 July 1918, the twenty six Baku Commissars attempted the evacuation of Bolshevik armed troops by sailing over the Caspian Sea to Astrakhan, but the ships were captured on 16 August by the military vessels of the Central Caspian Dictatorship. The Commissars were arrested and placed in Baku prison. On 28 August, he and his comrades were elected in absentia to the Baku Soviet. On 14 September, amidst the confusion as Baku fell to Turkish forces, Shahumyan and his fellow commissars either escaped or were released. In the most widely accepted version of events a group of Bolsheviks headed by Anastas Mikoyan broke into the prison and released Shahumyan. He and the other commissars then boarded a ship to Krasnovodsk, where upon arrival he was promptly arrested by anti-Bolshevik elements led by their commandant, Kuhn. Kuhn then requested further orders from the "Ashkhabad Committee", led by the Socialist Revolutionary Fyodor Funtikov, about what should be done with them. [citation needed]

Three days later, the British Major-General Wilfrid Malleson, on hearing of their arrest, contacted Britain's liaison-officer in Ashkhabad, Captain Reginald Teague-Jones, to suggest that the commissars be handed over to British forces in Meshed to be used as hostages in exchange for British citizens held by the Soviets. That same day, Teague-Jones attended the Committee's meeting in Ashkabad which had the task of deciding the fate of the Commissars. For some reason Teague-Jones did not communicate Malleson's request to the Committee, and later claimed he left before a decision was made and did not discover until the following day that the committee had eventually decided to issue orders that the commissars should be executed.[14][15] On the night of September 20, Shahumyan and the others were executed by a firing squad in a remote location between the stations of Pereval and Akhcha-Kuyma on the Trans-Caspian railway.

In 1956, the Observer published a letter written by a British staff officer who recounted a conversation he had had with Malleson, stricken with malaria at the time, on what was to be done to the commissars. Malleson replied that since the matter did not involve the British, then they should not concern themselves with the issue. The telegram that was sent told the authorities holding the commissars to dispose of them "as they sought fit."[16] Nevertheless, Malleson expressed his horror when he learned upon the ultimate fate that had befallen the commissars. [17]

Reburial

On January 2009, the Baku authorities' demolition of the 26 Commissars Memorial commemorating the 26 Baku Commissars began and was soon completed. It upset Armenia as the Armenian public believed that reburial is motivated by the reluctance of the Azerbaijanis (because of the Nagorno-Karabakh War) to have ethnic Armenians buried in the center of their capital.[18]

A scandal was created when Azerbaijani press reported that only 21 bodies were found buried in the park, as "Shahumian and four other Armenian commissars managed to escape their murderers".[18] It was quashed by Shahumian’s granddaughter Tatyana, now living in Moscow, who told the Russian daily Kommersant it was nonsense:“It is impossible to believe that they weren’t all buried. There is a film in the archives of 26 bodies being buried. Apart from this, my grandmother was present at the reburial.”[18]

Legacy

.JPG)

Following Shahumyan's death, the Soviet government depicted him as a fallen hero of the Russian revolution.[19] Shahumyan's close relationship with Lenin also increased the already heightened tensions between the British and the Soviets, who placed much of the blame on the British in complicity in the massacre.[20]

"And today we say with pride and love, that the great son of Armenian people Stepan is also the son of Azerbaijani people, all people of Transcaucasia, all multinational and united Soviet people". Heydar Aliev,[21] the leader of Soviet Azerbaijan

Throughout the Soviet Union's existence, Khankendi in the Nagorno-Karabakh region of the Azerbaijan SSR was renamed as Stepanakert, after Shahumyan. In 1992, Azerbaijan restored the pre-Soviet name of the town, Khankendi, while Nagorno-Karabakh authorities still refers to it as Stepanakert. The city of Dzhalal-Ogly in the Armenian SSR was also renamed, in Shahumyan's honor, Stepanavan, a name it has retained in post-Soviet Armenia. Streets in Lipetsk, Yekaterinburg, Stavropol and Rostov-on-Don (Russia), an avenue in Saint-Petersburg are named in Shahumian's honour. A statue of him erected in 1931 stands in Yerevan, the capital of Armenia. [citation needed]

Places named after Shahumyan

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Shaumyan, Goygol (The name has almost certainly been changed)

- Aşağı Ağcakənd, Goranboy (formerly Shaumyan, a disputed area claimed by the de facto Nagorno-Karabakh Republic)

- Şaumyanovka, the name has been changed to Məmişlər in 1992

- Russia

- Nagorno-Karabakh

- Stepanakert, the capital of the de facto Nagorno-Karabakh Republic

- Shahumian, a disputed area including Aşağı Ağcakənd, partially outside the de facto Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, in Azerbaijan

- Georgia

- Ukraine

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 (Armenian) Arzumanyan, M. Շահումյան, Ստեփան Գևորգի. "Yerevan, Armenian SSR, vol. viii", The Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia, 1982, pp. 431-34

- ↑ Panossian, Razmik. The Armenians: From Kings And Priests to Merchants And Commissars. New York: Columbia University Press, 2006 p. 211; ISBN 0-231-13926-8

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Hopkirk, Peter. On Secret Service East of Constantinople: The Plot to Bring Down the British Empire, Oxford University Press, 2001; ISBN 0-19-280230-5, pp 304-05, 322

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 (Russian) Michael Smith, Azerbaijan and Russia: Society and State: Traumatic Loss and Azerbaijani National Memory

- ↑ Suny, Ronald Grigor (1993). The revenge of the past:nationalism, revolution, and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Stanford University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 0-8047-2247-1.

- ↑ Stepan Shahumyan. Letters 1896-1918. State Publishing House of Armenia, Yerevan, 1959; pages 63-67.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 (Suny 1972, pp. 217–221)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Alex, Marshall (2009). The Caucasus Under Soviet Rule (Volume 12 of Routledge Studies in the History of Russia and Eastern Europe ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 89. ISBN 0415410126, 9780415410120 Check

|isbn=value (help). - ↑ Firuz Kazemzadeh. The Struggle for Transcaucasia, 1917–1921. Philosophical library, 1951, p. 75

- ↑ Michael P. Croissant, The Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict: Causes and Implications. New York: Praeger, 1998, pp. 14–15 ISBN 0-275-96241-5

- ↑ Human Rights Watch. "Playing the 'Communal Card': Communal Violence and Human Rights". Retrieved January 16, 2007.

- ↑ Fromkin, David. A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. New York: Owl, 1989 p. 356 ISBN 0-8050-6884-8

- ↑ Hopkirk. On Secret Service, p. 305

- ↑ C. Dobson & J. Miller The Day We Almost Bombed Moscow Hodder and Stoughton, 1986. pp 94-95.

- ↑ Leach, Hugh. Strolling About the Roof of the World: The First Hundred Years of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2002 p 26; ISBN 0-415-29857-1

- ↑ Leach. Strolling About the Roof, pp 26-27

- ↑ Leach. Strolling About the Roof, p 27

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Azerbaijan: Outcry at Commissars' Reburial, by Magerram Zeinalov and Gegham Vardanian, IWPR, 2009

- ↑ Panossian. The Armenians, p. 211

- ↑ Leach. Strolling About the Roof, p. 26

- ↑ Алиев Г.А. «Мужественный борец за дело Ленина, за коммунизм: к 100-летию со дня рождения С.Г. Шаумяна». Баку, 1978 г., стр. 26: «И сегодня мы с гордостью и любовью говорим, что великий сын армянского народа Степан – это и сын азербайджанского народа, всех народов Закавказья, всего многонационального и единого советского народа»).

Further reading

- Suny, Ronald Grigor. The Baku Commune, 1917-18. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972; ISBN 0-691-05193-3

|