Saint Christopher

| Saint Christopher | |

|---|---|

St. Christopher Carrying the Christ Child, by Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1485) | |

| Martyr | |

| Born |

unknown Canaan (Western accounts) or Marmarica (Eastern accounts) |

| Died |

c. 251 Asia Minor |

| Honored in |

Roman Catholicism Eastern Orthodoxy Lutheranism Oriental Orthodoxy Anglicanism |

| Feast | 25 July (Latin Church) , 9 May (Eastern Churches)[1] |

| Attributes | tree, branch, as a giant or ogre, carrying Jesus, spear, shield, as a dog-headed man |

| Patronage | bachelors, transportation (drivers, sailors, etc.), travelling (especially for long journeys), storms, Brunswick, Saint Christopher's Island (Saint Kitts), Island Rab, Vilnius, epilepsy, gardeners, holy death, toothache |

Saint Christopher (Greek: Ἅγιος Χριστόφορος, Ágios Christóforos) is venerated by Roman Catholics and Orthodox Christians as a martyr killed in the reign of the 3rd-century Roman Emperor Decius (reigned 249–251) or alternatively under the Roman Emperor Maximinus II Dacian (reigned 308–313). There appears to be confusion due to the similarity in names "Decius" and "Dacian".[2]

Legend

There are several legends associated with the life and death of Saint Christopher which first appeared in Greece and had spread to France by the 9th century. The 11th-century bishop and poet, Walter of Speyer, gave one version, but the most popular variations originated from the 13th-century Golden Legend.[3]

According to the legendary account of his life Christopher was initially called Reprobus.[4] He was a Canaanite 5 cubits (7.5 feet (2.3 m)) tall and with a fearsome face. While serving the king of Canaan, he took it into his head to go and serve "the greatest king there was". He went to the king who was reputed to be the greatest, but one day he saw the king cross himself at the mention of the devil. On thus learning that the king feared the devil, he departed to look for the devil. He came across a band of marauders, one of whom declared himself to be the devil, so Christopher decided to serve him. But when he saw his new master avoid a wayside cross and found out that the devil feared Christ, he left him and enquired from people where to find Christ. He met a hermit who instructed him in the Christian faith. Christopher asked him how he could serve Christ. When the hermit suggested fasting and prayer, Christopher replied that he was unable to perform that service. The hermit then suggested that because of his size and strength Christopher could serve Christ by assisting people to cross a dangerous river, where they were perishing in the attempt. The hermit promised that this service would be pleasing to Christ.

After Christopher had performed this service for some time, a little child asked him to take him across the river. During the crossing, the river became swollen and the child seemed as heavy as lead, so much that Christopher could scarcely carry him and found himself in great difficulty. When he finally reached the other side, he said to the child: "You have put me in the greatest danger. I do not think the whole world could have been as heavy on my shoulders as you were." The child replied: "You had on your shoulders not only the whole world but Him who made it. I am Christ your king, whom you are serving by this work." The child then vanished.

Christopher later visited the city of Lycia and there comforted the Christians who were being martyred. Brought before the local king, he refused to sacrifice to the pagan gods. The king tried to win him by riches and by sending two beautiful women to tempt him. Christopher converted the women to Christianity, as he had already converted thousands in the city. The king ordered him to be killed. Various attempts failed, but finally Christopher was decapitated.

Historical identification

Historical examination of the legends suggests Reprobus (Christopher) lived during the Christian persecutions of the Roman emperor Decius, and that he was captured and martyred by the governor of Antioch.[5] Historian David Woods has proposed that St. Christopher's remains were possibly taken to Alexandria by Peter of Attalia where he may have become identified with the Egyptian martyr Saint Menas.[5]

The legend of Saint Christopher records two important historical facts that identify him with the historical Saint Menas. The first is that the Greek and Latin legends of Saint Christopher identify him as belonging to the Third Valerian Cohort of the Marmantae (Latin: Cohors tertia Valeria, at Marmantarum), a military unit of Northern Africa of Marmarica (between modern day Libya and Egypt), recruited by none other than the Emperor Diocletian.[6] The second is that Saint Christopher was martyred in Antioch.

The martyrdom of Saint Menas corresponds to the details of the legend of Saint Christopher. The theory that identifies the two saints as one and the same concludes that the name "Christopher" meaning "Christ-bearer" was a title given to the name of the valiant Menas who died in Antioch. Since he was not a native of that land, his name was not known and so he was simply revered by his generic title: "Christophoros" or "Christ-Bearer."[7] Saint Menas happens to be the patron of travelers in the Coptic tradition,[7] which further supports an association with Saint Christopher who is the patron of travelers in the Greek and Latin traditions.

Part of Saint Christopher's story closely parallels that of Jason, who carried an old woman across a raging river- she was likewise described as being far heavier than she should have been and was actually Hera in disguise.

Veneration and patronage

Eastern Orthodox liturgy

The Eastern Orthodox Church venerates Christopher of Lycea with a Feast Day on May 9. The liturgical reading and hymns refer to his imprisonment by Decius who tempts Christopher with harlots before ordering his beheading.[8] The Kontakion in the Fourth Tone (hymn) reads:

Thou who wast terrifying both in strength and in countenance, for thy Creator's sake thou didst surrender thyself willingly to them that sought thee; for thou didst persuade both them and the women that sought to arouse in thee the fire of lust, and they followed thee in the path of martyrdom. And in torments thou didst prove to be courageous. Wherefore, we have gained thee as our great protector, O great Christopher.[8]

Roman Catholic liturgy

The Roman Martyrology remembers him on 25 July.[9] The Tridentine Calendar commemorated him on the same day only in private Masses. By 1954 his commemoration had been extended to all Masses, but it was dropped in 1970 as part of the general reorganization of the calendar of the Roman rite as mandated by the motu proprio, Mysterii Paschalis. His commemoration was described to be not of Roman tradition, in view of the relatively late date (about 1550) and limited manner in which it was accepted into the Roman calendar,[10] but his feast continues to be observed locally.[11]

Relics

The Museum of Sacred Art at Saint Justine's Church (Sveti Justina) in Rab, Croatia claims a gold-plated reliquary holds the skull of St. Christopher. According to church tradition, a bishop waved the relics from the city wall in 1358AD in order to end a siege of the city by an Ottoman army.[12]

Medals

Medallions with St. Christopher's name and image are commonly worn as pendants, especially by travelers, to show devotion and as a request for his blessing. Miniature statues are frequently displayed in automobiles. In French a widespread phrase for such medals is "Regarde St Christophe et va-t-en rassuré" ("Look at St Christopher and go on reassured"); Saint Christopher medals and holy cards in Spanish have the phrase "Si en San Cristóbal confías, de accidente no morirás" ("If you trust St. Christopher, you won't die in an accident"). In Austria an annual collection for providing vehicles for the use of missionaries is taken up on a Sunday close to the feast of Saint Christopher, asking people to contribute a very small sum of money for every kilometer that they have traveled safely during the year.[citation needed]

General patronage

St. Christopher is a widely popular saint, especially revered by athletes, mariners, ferrymen, and travelers.[3] He is revered as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers. He holds patronage of things related to travel and travelers — against lightning and pestilence — and patronage for archers; bachelors; boatmen; soldiers; bookbinders; epilepsy; floods; fruit dealers; fullers; gardeners; a holy death; mariners; market carriers; motorists and drivers; sailors; storms; surfers;[13] toothache; mountaineering; and transportation workers.

Patronage of places

Christopher is the patron saint of many places, including: Baden, Germany;[3] Barga, Italy; Brunswick, Germany;[3] Mecklenburg, Germany;[3] Rab, Croatia; Roermond, The Netherlands; Saint Christopher's Island (Saint Kitts); Toses in Catalonia, Spain; Mondim de Basto, Portugal; Agrinion, Greece; Vilnius, Lithuania; Riga, Latvia; Havana, Cuba; and Paete, Laguna, Philippines.

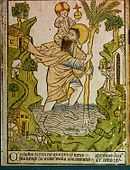

Depictions in art

Because St. Christopher offered protection to travelers and against sudden death, many churches placed images or statues of him, usually opposite the south door, so he could be easily seen.[11] He is usually depicted as a giant of a man, with a child on his shoulder and a staff in one hand.[14] In England, there are more wall paintings of St. Christopher than of any other saint;[11] in 1904, Mrs. Collier, writing for the British Archaeological Association, reported 183 paintings, statues, and other representations of the saint, outnumbering all others except for the Virgin Mary.[15]

| Depictions of Saint Christopher | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

In Eastern Orthodox icons, Saint Christopher is often represented with the head of a dog. The background to the dog-headed Christopher is laid in the reign of the Emperor Diocletian, when a man named Reprebus, Rebrebus or Reprobus (the "reprobate" or "scoundrel") was captured in combat against tribes dwelling to the west of Egypt in Cyrenaica. To the unit of soldiers, according to the hagiographic narrative, was assigned the name numerus Marmaritarum or "Unit of the Marmaritae", which suggests an otherwise-unidentified "Marmaritae" (perhaps the same as the Marmaricae Berber tribe of Cyrenaica). He was reported to be of enormous size, with the head of a dog instead of a man, apparently a characteristic of the Marmaritae. This Byzantine depiction of St. Christopher as dog-headed resulted from their misinterpretation of the Latin term Cananeus to read canineus, that is, "canine."[16]

The German bishop and poet Walter of Speyer portrayed St. Christopher as a giant of a cynocephalic species in the land of the Chananeans (the "canines" of Canaan in the New Testament) who ate human flesh and barked. Eventually, Christopher met the Christ child, regretted his former behavior, and received baptism. He, too, was rewarded with a human appearance, whereupon he devoted his life to Christian service and became an athlete of God, one of the soldier-saints.[17]

References in popular culture

See also

Notes

- ↑ (Greek) Ὁ Ἅγιος Χριστοφόρος ὁ Μεγαλομάρτυρας. 9 Μαΐου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- ↑ T.D. Barnes, The New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine (Cambridge, MA, 1982). pp. 65–66.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Mershman, F. (1908). St. Christopher. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved September 16, 2008

- ↑ Weniger, Francis X., "St. Christopher, Martyr", (1876)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 David Woods, "St. Christopher, Bishop Peter of Attalia, and the Cohors Marmaritarum: A Fresh Examination", Vigiliae Christianae, Vol. 48, No. 2 (Jun., 1994), p.170

- ↑ D.H. Farmer, The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (3rd ed.: Oxford, 1992), 97-98; or the note by V. Saxer in A. di Berardino (ed.), Encyclopedia of the Early Church I (New York, 1992), 165.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "The Origin of the Cult of St. Christopher".

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Christopher the Martyr of Lycea". Saints. Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ↑ Martyrologium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2001 ISBN 88-209-7210-7)

- ↑ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1969), p. 131

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Butler, Alban (2000). Peter Doyle, Paul Burns, ed. Butler's lives of the saints, Volume 7. Liturgical Press. pp. 198–99. ISBN 978-0-8146-2383-1. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ Letcher, Piers (June 18, 2013). Croatia (5th ed.). Bradt Travel Guide. p. 259-60. ISBN 9781841624532.

- ↑ Dioces of Orange hosts First Annual Blessing of the Waves in Surf City, Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange, September 15, 2008

- ↑ Magill, Frank Northen; J. Moose, Alison Aves (1998). Dictionary of World Biography: The ancient world. Taylor & Francis. pp. 239–44. ISBN 978-0-89356-313-4. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ Collier, Mrs. (1904). "Saint Christopher and Some Representations of Him in English Churches". Journal of the British Archaeological Association: 130–45. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ L. Ross, Medieval Art: A Topical Dictionary (Westport, 1996). p. 50.

- ↑ Walter of Speyer, Vita et passio sancti Christopher martyris, 75.

Further reading

- Bouquet, John A. (1930). A People's Book of Saints. London: Longman's.

- Butler, Alban (1956). Thurston, Herbert J.; Attwater, Donald, eds. Butler's lives of the saints. New York: Kenedy.

- Cunningham, Lawrence S. (1980). The meaning of saints. San Francisco: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-061649-0.

- Pridgeon, Ellie (2008). St Christopher Wall Paintings in English and Welsh Churches, c.1250-c.1520 (Thesis). University of Leicester: Unpublished PhD Thesis.

- Pridgeon, Ellie (2009). "The Function of St Christopher Imagery in Medieval Churches, c.1250 to c.1525: Wall Painting and Brass". Transactions of the Monumental Brass Society, Vol. 8.1.

- Pridgeon, Ellie (2013 Forthcoming). "National and International Trends in Hampshire Churches: A Chronology of St Christopher Wall Painting, c.1250-c.1530". Hampshire Studies, Vol. 68.

- de Voragine, Jacobus (1993). The golden legend: readings on the saints. William Ryan, trans. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press. ISBN 0-691-00865-5.

- Weinstein, Donald; Bell, Rudolph M. (1982). Saints and society: the 2 worlds of western Christendom, 1000–1700. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Pr. ISBN 0-226-89055-4.

- White, Helen (1963). Tudor Books of Saints and Martyrs. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Wilson, Stephen, ed. (1983). Saints and their cults: studies in religious sociology, folklore, and history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24978-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint Christopher. |

- Saint Christopher Website with information and references about St. Christopher.

- "The Life of Saint Christopher", The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints, Temple Classics, 1931 (Compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, Translated by William Caxton) at the Fordham University Medieval Sourcebook

- St. Christopher page at Christian Iconography

- St. Christopher in the Golden Legend: Latin original, English translation (Caxton)

- "The Passion of St. Christopher"

- Irish "Passion of St. Christopher"

- Medieval Wall Paintings Website by Ellie Pridgeon

- Saint Christopher engraved by E. Sadeler from the De Verda Collection

- Understanding the dog headed Icon of Saint Christopher at Orthodox Arts Journal.