Square matrix

In mathematics, a square matrix is a matrix with the same number of rows and columns. An n-by-n matrix is known as a square matrix of order n. For instance, this is a square matrix of order 4:

The entries aii form the main diagonal of a square matrix. For instance, the main diagonal of the 4-by-4 matrix above contains the elements a11 = 9, a22 = 11, a33 = 4, a44 = 10.

Any two square matrices of the same order can be added and multiplied.

Square matrices are often used to represent simple linear transformations, such as shearing or rotation. For example, if R is a square matrix representing a rotation (rotation matrix) and v is a column vector describing the position of a point in space, the product Rv yields another column vector describing the position of that point after that rotation. If v is a row vector, the same transformation can be obtained using vRT, where RT is the transpose of R.

Main diagonal

The entries aii (i = 1, ..., n) form the main diagonal of a square matrix. They lie on the imaginary line which runs from the top left corner to the bottom right corner of the matrix. For instance, the main diagonal of the 4-by-4 matrix above contains the elements a11 = 9, a22 = 11, a33 = 4, a44 = 10.

The diagonal of a square matrix from the top right to the bottom left corner is called antidiagonal or counterdiagonal.

Special kinds

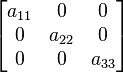

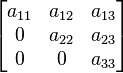

Name Example with n = 3 Diagonal matrix

Lower triangular matrix

Upper triangular matrix

Diagonal or triangular matrix

If all entries outside the main diagonal are zero, A is called a diagonal matrix. If only all entries above (or below) the main diagonal are zero, A is called a lower (or upper) triangular matrix.

Identity matrix

The identity matrix In of size n is the n-by-n matrix in which all the elements on the main diagonal are equal to 1 and all other elements are equal to 0, e.g.

It is a square matrix of order n, and also a special kind of diagonal matrix. It is called identity matrix because multiplication with it leaves a matrix unchanged:

- AIn = ImA = A for any m-by-n matrix A.

Symmetric or skew-symmetric matrix

A square matrix A that is equal to its transpose, i.e., A = AT, is a symmetric matrix. If instead, A was equal to the negative of its transpose, i.e., A = −AT, then A is a skew-symmetric matrix. In complex matrices, symmetry is often replaced by the concept of Hermitian matrices, which satisfy A∗ = A, where the star or asterisk denotes the conjugate transpose of the matrix, i.e., the transpose of the complex conjugate of A.

By the spectral theorem, real symmetric matrices and complex Hermitian matrices have an eigenbasis; i.e., every vector is expressible as a linear combination of eigenvectors. In both cases, all eigenvalues are real.[1] This theorem can be generalized to infinite-dimensional situations related to matrices with infinitely many rows and columns, see below.

Invertible matrix and its inverse

A square matrix A is called invertible or non-singular if there exists a matrix B such that

If B exists, it is unique and is called the inverse matrix of A, denoted A−1.

Definite matrix

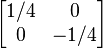

| Positive definite | Indefinite |

|---|---|

|

|

| Q(x,y) = 1/4 x2 + 1/4y2 | Q(x,y) = 1/4 x2 − 1/4 y2 |

Points such that Q(x,y) = 1 (Ellipse). |

Points such that Q(x,y) = 1 (Hyperbola). |

A symmetric n×n-matrix is called positive-definite (respectively negative-definite; indefinite), if for all nonzero vectors x ∈ Rn the associated quadratic form given by

- Q(x) = xTAx

takes only positive values (respectively only negative values; both some negative and some positive values).[4] If the quadratic form takes only non-negative (respectively only non-positive) values, the symmetric matrix is called positive-semidefinite (respectively negative-semidefinite); hence the matrix is indefinite precisely when it is neither positive-semidefinite nor negative-semidefinite.

A symmetric matrix is positive-definite if and only if all its eigenvalues are positive.[5] The table at the right shows two possibilities for 2-by-2 matrices.

Allowing as input two different vectors instead yields the bilinear form associated to A:

- BA (x, y) = xTAy.[6]

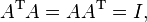

Orthogonal matrix

An orthogonal matrix is a square matrix with real entries whose columns and rows are orthogonal unit vectors (i.e., orthonormal vectors). Equivalently, a matrix A is orthogonal if its transpose is equal to its inverse:

which entails

where I is the identity matrix.

An orthogonal matrix A is necessarily invertible (with inverse A−1 = AT), unitary (A−1 = A*), and normal (A*A = AA*). The determinant of any orthogonal matrix is either +1 or −1. A special orthogonal matrix is an orthogonal matrix with determinant +1. As a linear transformation, every orthogonal matrix with determinant +1 is a pure rotation, while every orthogonal matrix with determinant −1 is either a pure reflection, or a composition of reflection and rotation.

The complex analogue of an orthogonal matrix is a unitary matrix.

Operations

Trace

The trace, tr(A) of a square matrix A is the sum of its diagonal entries. While matrix multiplication is not commutative as mentioned above, the trace of the product of two matrices is independent of the order of the factors:

- tr(AB) = tr(BA).

This is immediate from the definition of matrix multiplication:

Also, the trace of a matrix is equal to that of its transpose, i.e.,

- tr(A) = tr(AT).

Determinant

The determinant det(A) or |A| of a square matrix A is a number encoding certain properties of the matrix. A matrix is invertible if and only if its determinant is nonzero. Its absolute value equals the area (in R2) or volume (in R3) of the image of the unit square (or cube), while its sign corresponds to the orientation of the corresponding linear map: the determinant is positive if and only if the orientation is preserved.

The determinant of 2-by-2 matrices is given by

The determinant of 3-by-3 matrices involves 6 terms (rule of Sarrus). The more lengthy Leibniz formula generalises these two formulae to all dimensions.[7]

The determinant of a product of square matrices equals the product of their determinants:

- det(AB) = det(A) · det(B).[8]

Adding a multiple of any row to another row, or a multiple of any column to another column, does not change the determinant. Interchanging two rows or two columns affects the determinant by multiplying it by −1.[9] Using these operations, any matrix can be transformed to a lower (or upper) triangular matrix, and for such matrices the determinant equals the product of the entries on the main diagonal; this provides a method to calculate the determinant of any matrix. Finally, the Laplace expansion expresses the determinant in terms of minors, i.e., determinants of smaller matrices.[10] This expansion can be used for a recursive definition of determinants (taking as starting case the determinant of a 1-by-1 matrix, which is its unique entry, or even the determinant of a 0-by-0 matrix, which is 1), that can be seen to be equivalent to the Leibniz formula. Determinants can be used to solve linear systems using Cramer's rule, where the division of the determinants of two related square matrices equates to the value of each of the system's variables.[11]

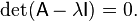

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors

A number λ and a non-zero vector v satisfying

- Av = λv

are called an eigenvalue and an eigenvector of A, respectively.[nb 1][12] The number λ is an eigenvalue of an n×n-matrix A if and only if A−λIn is not invertible, which is equivalent to

The polynomial pA in an indeterminate X given by evaluation the determinant det(XIn−A) is called the characteristic polynomial of A. It is a monic polynomial of degree n. Therefore the polynomial equation pA(λ) = 0 has at most n different solutions, i.e., eigenvalues of the matrix.[14] They may be complex even if the entries of A are real. According to the Cayley–Hamilton theorem, pA(A) = 0, that is, the result of substituting the matrix itself into its own characteristic polynomial yields the zero matrix.

Notes

- ↑ Horn & Johnson 1985, Theorem 2.5.6

- ↑ Brown 1991, Definition I.2.28

- ↑ Brown 1991, Definition I.5.13

- ↑ Horn & Johnson 1985, Chapter 7

- ↑ Horn & Johnson 1985, Theorem 7.2.1

- ↑ Horn & Johnson 1985, Example 4.0.6, p. 169

- ↑ Brown 1991, Definition III.2.1

- ↑ Brown 1991, Theorem III.2.12

- ↑ Brown 1991, Corollary III.2.16

- ↑ Mirsky 1990, Theorem 1.4.1

- ↑ Brown 1991, Theorem III.3.18

- ↑ Brown 1991, Definition III.4.1

- ↑ Brown 1991, Definition III.4.9

- ↑ Brown 1991, Corollary III.4.10