Spurious relationship

In statistics, a spurious relationship (or, sometimes, spurious correlation) is a mathematical relationship in which two events or variables have no direct causal connection, yet it may be wrongly inferred that they do, due to either coincidence or the presence of a certain third, unseen factor (referred to as a "confounding factor" or "lurking variable"). Suppose there is found to be a correlation between A and B. Aside from coincidence, there are three possible relationships:

- A causes B,

- B causes A,

- OR

- C causes both A and B.

In the last case there is a spurious correlation between A and B. In a regression model where A is regressed on B but C is actually the true causal factor for A, this misleading choice of independent variable (B instead of C) is called specification error.

Because correlation can arise from the presence of a lurking variable rather than from direct causation, it is often said that "Correlation does not imply causation".[citation needed]

A spurious relationship should not be confused with a spurious regression, which refers to a regression that shows significant results due to the presence of a unit root in both variables.[citation needed]

General example

An example of a spurious relationship can be illuminated by examining a city's ice cream sales. These sales are highest when the rate of drownings in city swimming pools is highest. To allege that ice cream sales cause drowning, or vice-versa, would be to imply a spurious relationship between the two. In reality, a heat wave may have caused both. The heat wave is an example of a hidden or unseen variable, also known as a confounding variable.

Another popular example is a series of Dutch statistics showing a positive correlation between the number of storks nesting in a series of springs and the number of human babies born at that time. Of course there was no causal connection; they were correlated with each other only because they were correlated with the weather nine months before the observations.[1] However Höfer et al. (2004) showed the correlation to be stronger than just weather variations as he could show in post reunification Germany that, while the number of clinical deliveries was not linked with the rise in stork population, out of hospital deliveries correlated with the stork population.[2]

Detecting spurious relationships

The term "spurious relationship" is commonly used in statistics and in particular in experimental research techniques, both of which attempt to understand and predict direct causal relationships (X → Y). A non-causal correlation can be spuriously created by an antecedent which causes both (W → X and W → Y). Intervening variables (X → W → Y), if undetected, may make indirect causation look direct. Because of this, experimentally identified correlations do not represent causal relationships unless spurious relationships can be ruled out.

Experiments

In experiments, spurious relationships can often be identified by controlling for other factors, including those that have been theoretically identified as possible confounding factors. For example, consider a researcher trying to determine whether a new drug kills bacteria; when the researcher applies the drug to a bacterial culture, the bacteria die. But to help in ruling out the presence of a confounding variable, another culture is subjected to conditions that are as nearly identical as possible to those facing the first-mentioned culture, but the second culture is not subjected to the drug. If there is an unseen confounding factor in those conditions, this control culture will die as well, so that no conclusion of efficacy of the drug can be drawn from the results of the first culture. On the other hand, if the control culture does not die, then the researcher cannot reject the hypothesis that the drug is efficacious.

Non-experimental statistical analyses

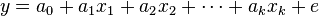

Disciplines whose data are mostly non-experimental, such as economics, usually employ observational data to establish causal relationships. The body of statistical techniques used in economics is called econometrics. The main statistical method in econometrics is multivariate regression analysis. Typically a linear relationship such as

is hypothesized, in which  is the dependent variable (hypothesized to be the caused variable),

is the dependent variable (hypothesized to be the caused variable),  for j = 1, ..., k is the jth independent variable (hypothesized to be a causative variable), and

for j = 1, ..., k is the jth independent variable (hypothesized to be a causative variable), and  is the error term (containing the combined effects of all other causative variables, which must be uncorrelated with the included independent variables). If there is reason to believe that none of the

is the error term (containing the combined effects of all other causative variables, which must be uncorrelated with the included independent variables). If there is reason to believe that none of the  s is caused by y, then estimates of the coefficients

s is caused by y, then estimates of the coefficients  are obtained. If the null hypothesis that

are obtained. If the null hypothesis that  is rejected, then the alternative hypothesis that

is rejected, then the alternative hypothesis that  and equivalently that

and equivalently that  causes y cannot be rejected. On the other hand, if the null hypothesis that

causes y cannot be rejected. On the other hand, if the null hypothesis that  cannot be rejected, then equivalently the hypothesis of no causal effect of

cannot be rejected, then equivalently the hypothesis of no causal effect of  on y cannot be rejected. Here the notion of causality is one of contributory causality: If the true value

on y cannot be rejected. Here the notion of causality is one of contributory causality: If the true value  , then a change in

, then a change in  will result in a change in y unless some other causative variable(s), either included in the regression or implicit in the error term, change in such a way as to exactly offset its effect; thus a change in

will result in a change in y unless some other causative variable(s), either included in the regression or implicit in the error term, change in such a way as to exactly offset its effect; thus a change in  is not sufficient to change y. Likewise, a change in

is not sufficient to change y. Likewise, a change in  is not necessary to change y, because a change in y could be caused by something implicit in the error term (or by some other causative explanatory variable included in the model).

is not necessary to change y, because a change in y could be caused by something implicit in the error term (or by some other causative explanatory variable included in the model).

Regression analysis controls for other relevant variables by including them as regressors (explanatory variables). This helps to avoid mistaken inference of causality due to the presence of a third, underlying, variable that influences both the potentially causative variable and the potentially caused variable: its effect on the potentially caused variable is captured by directly including it in the regression, so that effect will not be picked up as a spurious effect of the potentially causative variable of interest. In addition, the use of multivariate regression helps to avoid wrongly inferring that an indirect effect of, say x1 (e.g., x1 → x2 → y) is a direct effect (x1 → y).

Just as an experimenter must be careful to employ an experimental design that controls for every confounding factor, so also must the user of multiple regression be careful to control for all confounding factors by including them among the regressors. If a confounding factor is omitted from the regression, its effect is captured in the error term by default, and if the resulting error term is correlated with one (or more) of the included regressors, then the estimated regression may be biased or inconsistent (see omitted variable bias).

See also

- Causality

- Correlation does not imply causation

- Omitted-variable bias

- Post hoc fallacy

- Specification (regression)

Footnotes

- ↑ Sapsford, Roger; Jupp, Victor, eds. (2006). Data Collection and Analysis. Sage. ISBN 0-7619-4362-5.

- ↑ Höfer, Thomas; Hildegard Przyrembel and Silvia Verleger (2004). "New evidence for the Theory of the Stork". Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 18 (1): 18–22. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2003.00534.x.

References

- Pearl, Judea (2000). Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521773628.

- Yule, G. U. (1926). "Why do we sometimes get nonsense correlations between time series?—A study in sampling and the nature of time series". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 89 (1): 1–64. JSTOR 2341482.

External links

- Burns, William C., "Spurious Correlations", 1997.

- "The Art and Science of Cause and Effect": a slide show and tutorial lecture by Judea Pearl