Spin quantum number

In atomic physics, the spin quantum number is a quantum number that parameterizes the intrinsic angular momentum (or spin angular momentum, or simply spin) of a given particle. The spin quantum number is the fourth of a set of quantum numbers (the principal quantum number, the azimuthal quantum number, the magnetic quantum number, and the spin quantum number), which describe the unique quantum state of an electron and is designated by the letter s.

Derivation

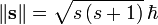

As a quantized angular momentum, (see angular momentum quantum number) it holds that

where

-

is the quantized spin vector

is the quantized spin vector -

is the norm of the spin vector

is the norm of the spin vector -

is the spin quantum number associated with the spin angular momentum

is the spin quantum number associated with the spin angular momentum -

is the reduced Planck constant.

is the reduced Planck constant.

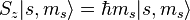

Given an arbitrary direction z (usually determined by an external magnetic field) the spin z-projection is given by

where ms is the secondary spin quantum number, ranging from −s to +s in steps of one. This generates 2 s + 1 different values of ms.

The allowed values for s are non-negative integers or half-integers. Fermions (such as the electron, proton or neutron) have half-integer values, whereas bosons (e.g., photon, mesons) have integer spin values.

Algebra

The algebraic theory of spin is a carbon copy of the Angular momentum in quantum mechanics theory. First of all, spin satisfies the fundamental commutation relation:

![[S_{i},S_{j}]=i\hbar \epsilon _{{ijk}}S_{k}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/8/d/9/f/8d9f476ea94ffcbbb6a468e7fe075d6e.png) ,

, ![\left[S_{i},S^{2}\right]=0](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/1/d/9/f/1d9fdcb6b99e9ca6504fdec0f7f08a03.png)

where εlmn is the (antisymmetric) Levi-Civita symbol. This means that it is impossible to know two coordinates of the spin at the same time because of the restriction of the Uncertainty principle.

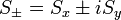

Next, the eigenvectors of  and

and  satisfy:

satisfy:

where  are the creation and annihilation (or "raising" and "lowering" or "up" and "down") operators.

are the creation and annihilation (or "raising" and "lowering" or "up" and "down") operators.

Electron spin

Early attempts to explain the behavior of electrons in atoms focused on solving the Schrödinger wave equation for the hydrogen atom, the simplest possible case, with a single electron bound to the atomic nucleus. This was successful in explaining many features of atomic spectra.

The solutions required each possible state of the electron to be described by three "quantum numbers". These were identified as, respectively, the electron "shell" number n, the "orbital" number l, and the "orbital angular momentum" number m. Angular momentum is a so-called "classical" concept measuring the momentum[citation needed] of a mass in circular motion about a point. The shell numbers start at 1 and increase indefinitely. Each shell of number n contains n² orbitals. Each orbital is characterized by its number l, where l takes integer values from 0 to n−1, and its angular momentum number m, where m takes integer values from +l to −l. By means of a variety of approximations and extensions, physicists were able to extend their work on hydrogen to more complex atoms containing many electrons.

Atomic spectra measure radiation absorbed or emitted by electrons "jumping" from one "state" to another, where a state is represented by values of n, l, and m. The so-called "Transition rule" limits what "jumps" are possible. In general, a jump or "transition" is allowed only if all three numbers change in the process. This is because a transition will be able to cause the emission or absorption of electromagnetic radiation only if it involves a change in the electromagnetic dipole of the atom.

However, it was recognized in the early years of quantum mechanics that atomic spectra measured in an external magnetic field (see Zeeman effect) cannot be predicted with just n, l, and m. A solution to this problem was suggested in early 1925 by George Uhlenbeck and Samuel Goudsmit, students of Paul Ehrenfest (who rejected the idea), and independently by Ralph Kronig, one of Landé's assistants. Uhlenbeck, Goudsmit, and Kronig introduced the idea of the self-rotation of the electron, which would naturally give rise to an angular momentum vector in addition to the one associated with orbital motion (quantum numbers l and m).

The spin angular momentum is characterized by a quantum number; s = 1/2 specifically for electrons. In a way analogous to other quantized angular momenta, L, it is possible to obtain an expression for the total spin angular momentum:

where

-

is the reduced Planck constant.

is the reduced Planck constant.

The hydrogen spectra fine structure is observed as a doublet corresponding to two possibilities for the z-component of the angular momentum, where for any given direction z:

whose solution has only two possible z-components for the electron. In the electron, the two different spin orientations are sometimes called "spin-up" or "spin-down".

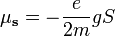

The spin property of an electron would give rise to magnetic moment, which was a requisite for the fourth quantum number. The electron spin magnetic moment is given by the formula:

where

- e is the charge of the electron

- g is the Landé g-factor

and by the equation:

where  is the Bohr magneton.

is the Bohr magneton.

When atoms have even numbers of electrons the spin of each electron in each orbital has opposing orientation to that of its immediate neighbor(s). However, many atoms have an odd number of electrons or an arrangement of electrons in which there is an unequal number of "spin-up" and "spin-down" orientations. These atoms or electrons are said to have unpaired spins that are detected in electron spin resonance.

Detection of spin

When lines of the hydrogen spectrum are examined at very high resolution, they are found to be closely spaced doublets. This splitting is called fine structure, and was one of the first experimental evidences for electron spin. The direct observation of the electron's intrinsic angular momentum was achieved in the Stern–Gerlach experiment.

The Stern–Gerlach experiment

The theory of spatial quantization of the spin moment of the momentum of electrons of atoms situated in the magnetic field needed to be proved experimentally. In 1920 (two years before the theoretical description of the spin was created) Otto Stern and Walter Gerlach observed it in the experiment they conducted.

- The atoms of silver from the source that was the furnace with boiling silver were leaded to the vacuum space. There (thanks to the thin slides) the flat beam of those atoms was created. Then the beam got into non-homogeneous magnetic field and incidenced a photographic plate. Using classic physical laws we would expect the single picture of the beam on the plate. Whereas the beam of the atoms passing through not homogeneous magnetic field undergoes splitting. That is why Otto Stern and Walter Gerlach received the two lines on the photographic plate.

- The phenomenon can be explained with the spatial quantization of the spin moment of momentum. In atoms the electrons are typically located in such way that in each pair of electrons there is one of the upward spin and one of the downward spin. So the whole spin of such pair is equal to zero. But, in the atom of silver on the outer shell, there is a single electron whose spin is not balanced by any electron.

- The circulation causes some magnetic dipole moment (it's like it was a very small magnet). There is a force moment in the magnetic field influencing the dipole that is turning it until its position is the same as the direction of the field B. There is some other force influencing the dipole in the field. When the dipole is directed the same as the magnetic field then the dipole is pulled by that force toward the strongest field. But, if the dipole is directed opposite to the field's, it is pushed away from the strongest field.

- So the atom of silver having one electron on the outer shell can be pulled in or out the space of a strongest magnetic field, what depends on the value of the magnetic spin quantum number. When the spin of the electron is equal +1/2 the atom is pulled out and when the spin is equal −1/2 the atom is pulled in. So during passing through the non-homogeneous magnetic field the beam of the atoms of silver undergoes splitting into the two beams. Each of them consists of atoms whose outer electrons are of the same spin.

- In 1927 Phipps and Taylor conducted a similar experiment. This time they used atoms of hydrogen, not silver. They also observed that the beam of atoms undergoes splitting into two beams.

- Later scientists conducted experiments using other atoms that have only one electron on the outer shell (copper, gold, sodium, potassium). Every time there were two lines achieved on the photographic plate.

- In the atom, not only electrons have spin: The atomic nucleus also may have spin. But protons and neutrons are much heavier than electrons (about 1836 times), and the magnetic dipole moment is inversely proportional to the mass. So the nuclear magnetic dipole momentum is much smaller than that of the whole atom. This small magnetic dipole was later measured by Stern, Frisch and Easterman.

Dirac equation solves spin

When the idea of electron spin was first introduced in 1925, even Wolfgang Pauli had trouble accepting Ralph Kronig's model. The problem was not that a rotating charged particle would have given rise to a magnetic field but that the electron was so small that the equatorial speed of the electron would have to be greater than the speed of light for the magnetic moment to be of the observed strength.

In 1930, Paul Dirac developed a new version of the Wave Equation which was relativistically invariant (unlike Schrödinger's one), and predicted the magnetic moment correctly, and at the same time treated the electron as a point particle. In the Dirac equation all four quantum numbers including the additional quantum number, s arose naturally during its solution.

See also

- Total angular momentum quantum number

- Basic quantum mechanics

External references