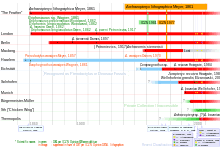

Specimens of Archaeopteryx

Archaeopteryx fossils from the quarries of Solnhofen limestone represent the most famous and well-known fossils from this area. They are highly significant to paleontology and avian evolution in that they document the fossil record's oldest-known birds.[1]

Over the years, eleven body fossil specimens of Archaeopteryx and a feather that may belong to it have been found. All of the fossils come from the upper Jurassic lithographic limestone deposits, quarried for centuries, near Solnhofen, Germany.[2][3]

The feather

.jpg)

The initial discovery, a single feather, was unearthed in 1860 or 1861 and described in 1861 by Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer. The fossil consists of two counterslabs, designated BSP 1869 VIII 1 (main slab) and MB Av. 100 (counterslab). Its two counterslabs are currently located at the Bavarian State Collection of Paleontology and Geology of Munich University and the Humboldt Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, respectively.[1] This feather is generally assigned to Archaeopteryx and was the initial holotype, but whether it actually is a feather of this species or another, as yet undiscovered, avialan is unknown. There are some indications it is indeed not from the same animal as most of the skeletons (the "typical" A. lithographica).[4]

History

The feather was first described in a series of correspondence letters between Hermann von Meyer and Heinrich Georg Bronn, the editor of the German Jahrbuch für Mineralogie journal. Examining the fossil on both counterpart split slabs, von Meyer immediately recognized it as an asymmetrical bird feather, most likely from a wing, with an "obtusely angled tip" and a "here and there gaping vane", and noted its blackish appearance. Six weeks after writing this first letter in August 1861, von Meyer wrote again to the editor stating that he had been informed of a nearly-complete skeleton of a feathered animal from the same lithographic shale deposits, which would later be known as the London specimen. Coincidentally, von Meyer proposed the name Archaeopteryx lithographica for the feather, but not for the skeleton. Therefore the official name of the animal was originally linked to the single feather rather than any actual skeleton, and is formally considered the original holotype.[1][5]

Though 1860 is often the year named for the feather's discovery, there is no proof of this date, and some authors consider it more likely to have been found in 1861, as it seems reasonable that von Meyer's original letter was likely sent not longer after it came into his possession. The feather was discovered in the partition of the Solnhofen Community Quarry located southwest of the municipality of Solnhofen in a forested district known as Truhenleite, which was opened in 1738. 25 meters of the limestone profile of Upper Solnhofen strata are exposed here, but no information was given about which horizon the feather originated from, though the fossil's dark colour may indicate that it came from a deeper level where it was protected from weathering. Today, the quarry is abandoned and the location is built up.[1]

Original description

Von Meyer published his official description of the feather in the journal Palaeontographica in April 1862, wherein he expressed some doubt of its exact age and affinity. In his original description von Meyer mentioned neither the original discoverer nor the collector by name, and also omitted any diagnostic information about its prior ownership. It wasn't until the year of von Meyer's death, 1869, that the main slab came into the Munich collections. The feather's counterslab was acquired by the Humboldt Museum für Naturkunde in 1876, after having been part of the private collection of von Fischer, a Munich physician.[1]

There was also some initial uncertainty as to whether the fossil represented a real feather as in modern birds, though von Meyer pointed out that he could detect no morphological difference between the fossil imprint and modern feathers, and was able to recognize the central shaft, the barbs and the barbules. He described the lower end of the shaft (the calamus) as being less clearly imprinted than the rest, and concluded that the feather may have belonged to a juvenile individual for whom the shaft was still soft. Von Meyer also noted that due to having been compressed, the vane was split in several places. As part of his original description von Meyer compared the feather to that of a partridge, noting that the only discernable difference was in being slightly smaller and less rounded at the end.[1][6]

Some doubt also existed at first as to whether the feather was a real fossil from the Solnhofen lithographic limestone. The preservation was regarded by von Meyer as unusual and therefore suspicious, as it appeared to be "transformed into a black substance" that reminded him of dendrites, which are inorganic pseudofossils. He thought it was possible that someone had skillfully painted the feather onto the stone. However, he could not conceive of an artificial way in which such a perfect feather - especially as it was reproduced in a perfect mirror image on bother counterslabs - could be created by a human hand, and therefore concluded the feather must be genuine.[1]

Though von Meyer was certain that the fossil feather was real, he was very reluctant to assign it with certainty to a bird, noting that the concurrent feathered skeleton could be "a feathered animal which differs from our birds essentially". It is interesting to note that his reluctance to link feathers to birds with certainty was prophetic, as it predated the discovery of very advanced, birdlike feathers on non-avian theropod dinosaurs by well over a century.[1][7]

Additional research

After von Meyer's original 1862 description, no additional analyses of the feather were performed until 1996, when a detailed assessment of its morphology, function, taxonomy and taphonomy was produced by Griffiths, and the feather was later studied under ultraviolet light in 2004 by Tischlinger and Unwin.[1] The feather was further studied using scanning electron microscopy technology and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis in 2011.[8]

Morphology

The feather has a total length of 58 mm, and the vane is 12 mm at the widest margin. The end of the feather has an obtuse angle of 110°, while the barbs branch off from the rachis at an angle of around 25°. The barbs branch noticeably into barbules, as in the feathers of modern birds. The base of the feather consists of plumulaceous barbs which are unconnected to one another and result in a down-like appearance. This tuft of down led Griffiths to conclude that Archaeopteryx might have been endothermic in that it implies the use of thermal insulation.[1][9]

The feather is clearly asymmetrical, which has been interpreted by many scientists to be a clear indication of its aerodynamic function as a flight feather.[10] As the feather bears little resemblance to the retrices of the other full Archaeopteryx skeletons, it is generally thought to be a wing feather: Griffiths and others have concluded it was a remex, while Carney in 2012 interpreted it to be a covert feather.[8] The feather has a relatively low degree of asymmetry, which Speakman and Thompson in 1994 concluded to indicate it as a secondary remex.[11] If this is the case, then it would have originated from an animal smaller than even the Eichstätt specimen, which is the smallest Archaeopteryx specimen known to date. This is consistent with von Meyer's much earlier interpretation of the feather as having belonged to a juvenile.[1]

The feather was studied under UV light by Tischlinger and Unwin in 2004, and they found that a pattern of dark and light spots were visible on each side of the shaft. This was interpreted as remnants of the original pigment design that would have been on the feather in life, similar to the spots and bars on the feathers of modern partridges or birds of prey.[12] It isn't possible to be certain of this, however, so conclusions about the colouration and patterning of the plumage cannot be drawn with certainty from this study.[1]

In 2011, graduate student Ryan Carney and colleagues performed the first colour study on an Archaeopteryx specimen with the fossil of this single feather. Using scanning electron microscopy technology and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis, the team was able to detect the structure of melanosomes in the fossil. The resultant structure was then compared to that of 87 modern bird species and was determined with a high percentage of likelihood to be black in colour. While the study does not mean that Archaeopteryx was entirely black, it does suggest that it had some black colouration which included the coverts (or possibly the secondary remiges). Carney pointed out that this is consistent with what we know of modern flight characteristics, in that black melanosomes have structural properties that strengthen feathers for flight.[8][13]

Taphonomy

The preservation of the fossil feather is unusual. In contrast to the feather imprints found on the full skeletons of Archaeopteryx, the isolated feather is preserved as a dark film, which could be composed either of organic matter (as in most fossil feathers) or as inorganic minerals. Though it is theoretically possible to determine which it is, studying the physical component of the preserved dark film would require taking away a certain amount of the material from the fossil, and no curator was willing grant permission for such damage to a valuable holotype specimen. Since dendrites are very common in Solnhofen limestones, it is possible that the structures could have formed along the cracks and fissures of the limestone, and subsequently penetrated the minute hollow left in the limestone from the decay of the feather. The manganese dioxide solutions could then have imitated all of the fine detail of the original feather, creating a pseudomorph.[1]

Billy and Cailleux, in 1969, proposed a mechanism by which bacteria could have created a similar effect with manganese dioxide.[14] Davis and Briggs (1995) studied that the fossilization of feathers often involves the formation of bacterial mats, and found fossil bacteria with scanning electron microscopy upon the fossil feathers of birds from the Eocene Green River Formation and the Cretaceous Crato Formation.[15] However, an SEM investigation on the isolated Archaeopteryx feather would also require a sample to be extracted, and has not yet been done.[1]

One explanation for the marked difference in preservation between the isolated feather and the body feathers of known skeletal specimens is that the single feather was likely shed during molt. This means that it would not have been connected to the body by ligaments and connective tissue, and was probably lost on dry land and was washed or blown into the lagoon. The feather could have been colonized by bacteria during the feather's travel time, as it likely did not sink to the bottom immediately after being shed, which could have initiated the taphonomic processes that rely on the presence of bacteria.[1][4]

One unique feature of the isolated feather specimen is that it features a series of small black spots and filaments, which are around the same diameter as the feather barbs, both across the feather and along the surfaces of both slabs. Von Meyer pointed out these structures in his original description, and described them as being similar to "short hairs" which probably originated from the animal's skin. However, due to being deposited both on the upper and lower surface of the slabs which indicates they were deposited at different times, it is more likely that they are remnants of plant material that may have been ground down before being washed into the lagoon along with the feather.[1][5]

Taxonomy

Archaeopteryx lithographica was initially named for this original feather, rather than the full skeleton that was found around the same time, and the feather was originally the formal type specimen and holotype for the species. There are obvious problems with this idea, such as the fact that the feather may have come from a juvenile, or possibly another species altogether. The distal obtuse angle at the tip is not a feature found on the feathers of any other Archaeopteryx skeleton with integument imprints. It is possible, however, that the strange angle of the tip is an artifact caused by inappropriate preservation, as pointed out by Tischlinger and Unwin in 2004.[12] Speakman and Thomson also found that the degree of asymmetry is different in this isolated feather than it is in similar feathers of the skeletal specimens of Archaeopteryx - the asymmetry of feathers in the skeletons ranged from 1.44 in the London specimen to 1.46 in the Berlin specimen, while the single feather as an asymmetry ratio of 2.2.[11] These measurements are not conclusive, however, because the differences in asymmetry may be due to incomplete distal ends, overlapping, or monomorphic scaling, and may be meaningless for ascertaining the phylogenetic position of this feather. Whether the feather truly belongs to Archaeopteryx or to a different taxon remains unresolved, but what is certain is that the feather does represent the oldest example of a bird feather in the fossil record.[1]

The London specimen

The first skeleton, known as the London Specimen (BMNH 37001),[16] was unearthed in 1861 near Langenaltheim, Germany and perhaps given to a local physician Karl Häberlein in return for medical services. He then sold it for £700 to the Natural History Museum in London, where it remains.[17] Missing most of its head and neck, it was described in 1863 by Richard Owen as Archaeopteryx macrura, allowing for the possibility it did not belong to the same species as the feather. In the subsequent 4th edition of his On the Origin of Species,[18] Charles Darwin described how some authors had maintained "that the whole class of birds came suddenly into existence during the eocene period; but now we know, on the authority of Professor Owen, that a bird certainly lived during the deposition of the upper greensand; and still more recently, that strange bird, the Archeopteryx, with a long lizard-like tail, bearing a pair of feathers on each joint, and with its wings furnished with two free claws, has been discovered in the oolitic slates of Solnhofen. Hardly any recent discovery shows more forcibly than this how little we as yet know of the former inhabitants of the world."[19]

The Greek term "pteryx" (πτέρυξ) primarily means "wing", but can also designate merely "feather". Von Meyer suggested this in his description. At first he referred to a single feather which appeared like a modern bird's remex (wing feather), but he had heard of and been shown a rough sketch of the London specimen, to which he referred as a "Skelet eines mit ähnlichen Federn bedeckten Thieres" ("skeleton of an animal covered in similar feathers"). In German, this ambiguity is resolved by the term Schwinge which does not necessarily mean a wing used for flying. Urschwinge was the favored translation of Archaeopteryx among German scholars in the late 19th century. In English, "ancient pinion" offers a rough approximation.

History

Hermann von Meyer learned of the discovery of what would later be known as the London Specimen before he published his analysis of the single Archaeopteryx feather. In September 1861 he wrote to the "Neues Jahrbuch" about being informed of the discovery by Friedrich Ernst Witte, an avid fossil collector and jurist by profession, and commented on the coincidental nature of learning of a feathered skeleton from the Solnhofen strata while studying the feather. Witte had visited a well-known collector of Solnhofen fossils, Dr. Karl Häberlein, in the summer of 1861 whereupon he had first seen this "skeleton of an animal furnished with feathers" at the fossil collector's home in Pappenheim. Clearly recognizing the significance of such a fossil, he then immediately wrote to Hermann von Meyer as well as Andreas Wagner, the Munich Professor of Paleontology. He subsequently traveled to Munich in order to convince Wagner to purchase the fossil for the Bavarian State Collections.[1]

Witte later recounted his visit with Wagner in 1863 in a letter to the editor of "Neues Jahrbuch":

When I first told him of the specimen in order to urge him to buy it for the Munich Collections, he reacted with absolute incredulity, since, according to his view, a feathered creature could only be a bird. But, after his system of creation, a bird could not have existed as early as in the Jurassic Period...

He goes on to describe the visit paid to the fossil by Wagner's assistant after being told of the Solnhofen fossil feather published by von Meyer. Despite this, he still stuck to his conviction that the animal represented a saurian, and named it Griphosaurus.[1][20]

Witte is regarded as being the main person responsible for alerting the scientific community of existence and significance of the London Specimen. He took a remarkably prescient standpoint in claiming that the debate of whether it was allied with birds or reptiles was irrelevant, and that the animal "has characters of both and is strictly none of them". The only relevant question, he said, was which characters predominate, and which class it must be allied with "for the time being".[1][20]

It is not known with certainty how Dr. Häberlein first came into possession of the specimen, though as it was found in the section of the Solnhofen Community Quarry belonging to Johann Friedrich Ottman, it is reasonable to assume that Ottman sold the fossil to Häberlein directly. Häberlein offered his feathered fossil to the State Paleontological Collection in Munich after its director, Albert Oppel, examined it in 1861 in Pappenheim. Though Oppel had not been granted permission by the owner to draw the fossil, he retained an accurate memory of its appearance and was able to reproduce it upon his return. The sketch was later given to Wagner, who wanted the honor of describing the fossil first.[1]

Shortly after, Wagner presented a talk at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences, which was later published as an article in 1862. In this talk, Wagner gives a detailed account of the curious combination of avian and saurian features that made the fossil so unique and mysterious. He describes the feather imprints of the fossil to be "those of true birds", and went on to describe other features, like the long tail, that bore "not the least resemblance to that of a bird". He compares the fossil to Rhamphorhynchus, a Solnhofen pterosaur which also possessed a long, bony tail. He regarded the creature as a "mongrel" of bird and reptile, the whole of which was incomprehensible to him.[1][21]

Despite these comments, Wagner made it clear that he did not regard the feather-like imprints as proof of real bird feathers. He claimed that the imprints may merely be "peculiar adornments" and that he did not hesitate to regard it as a reptile. Wellnhofer points out that his reasoning behind this opinion was likely due to his anti-Darwinist approach to paleontology, which is confirmed in Wagner's November 1862 talk, wherein he makes a statement on the new fossil with the intention to "ward off Darwinian misinterpretations of our new Saurian".[21] He was uncomfortable with the idea that a "transitional fossil" could exist, and in Wagner's creation-centered interpretation of paleontology, there was no room for a form intermediate between reptile and bird.[1]

Purchase by the British Museum

While the arguments about the nature of the new feathered animal were underway, negotiations were taking place between Dr. Häberlein and the British Museum of London, as the offer of sale to the Bavarian State Collection had failed. On February 28, 1862, a letter was written by George Robert Waterhouse, the Keeper of the Geological Department of the British Museum, to Häberlein asking if he'd be willing to sell the fossil. This letter was written at the request of Richard Owen, who was the Superintendent of the British Museum's Natural History division. Häberlein was interested in selling, but made it clear that he had a lot of other interested potential buyers from a variety of countries, and the competition was driving the price quite high.[22] He was 74 years old and quite ill at the time, and wished to sell his entire collection of Solnhofen fossils, which was fairly substantial. His original price for his full collection was set at 750 pounds sterling.[23] Owen presented this letter to his museum, and was thereafter sent to Pappenheim to negotiate with Häberlein, but had orders to spend no more than 500 pounds. Häberlein, however, was unwilling to part with the fossil for less than 650 pounds.[1][24]

For several weeks afterwards, the museum struggled to find a solution that would work within the limits of their budget. Waterhouse and Owen finally offered that Häberlein would be paid a sum of 450 pounds for the Archaeopteryx specimen during that year, and an additional 250 pounds would be paid the following year for the rest of the collection. Häberlein agreed to this somewhat grudgingly, and the fossil was packed and shipped to London at the end of September 1862.[25] As promised, the rest of the collection - totaling 1,756 Solnhofen specimens - was purchased the following year. In this way the London Museum came to acquire a truly important collection of fossils, many of them quite rare or undescribed at the time.[1]

Welnhofer remarks that it was likely not the price that kept the Bavarian State Paleontological Collection in Munich from acquiring the fossil, but rather the hesitating attitude of Andreas Wagner which delayed any action. Following Wagner's death in 1861, negotiations with Häberlein certainly would have been all the more difficult. In the wake of this important transaction of the first Archaeopteryx body fossil, many German scientists bitterly regretted its departure from its native land to London. Frankfurt zoologist David Friedrich Weinland, for instance, commented that "the English became greedy for the treasure".[1][26]

The collection's final selling price of 700 pounds, or 8,400 Bavarian guldens, was calculated at approximately 18,340 British pounds in 1987,[27] though that calculation may be low. In any case, it was considered to be a small fortune at the time. Häberlein allegedly used the payment as a dowry for one of his daughters.[1][24]

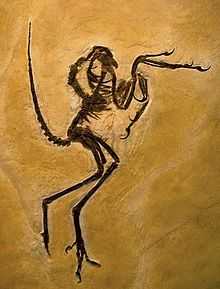

The Berlin specimen

.jpg)

The Berlin Specimen (HMN 1880) was discovered in 1874 or 1875 on the Blumenberg near Eichstätt, Germany, by farmer Jakob Niemeyer. He sold this precious fossil for the money to buy a cow in 1876, to inn-keeper Johann Dörr, who again sold it to Ernst Otto Häberlein, the son of K. Häberlein. Placed on sale between 1877 and 1881, with potential buyers including O.C. Marsh of Yale University's Peabody Museum, it was eventually bought by the Humboldt Museum für Naturkunde, where it is now displayed, for 20,000 Goldmark. The transaction was financed by Ernst Werner von Siemens, founder of the famous company that bears his name.[2] Described in 1884 by Wilhelm Dames, it is the most complete specimen, and the first with a complete head. It was in 1897 named by Dames as a new species, A. siemensii; a recent evaluation supports the A. siemensii species identification.[28]

The Maxberg specimen

Composed of a torso, the Maxberg specimen (S5) was discovered in 1956 near Langenaltheim; it was brought to the attention of professor Florian Heller in 1958 and described by him in 1959. It is currently missing, though it was once exhibited at the Maxberg Museum in Solnhofen. It belonged to Eduard Opitsch, who loaned it to the museum until 1974. After his death in 1991, the specimen was discovered to be missing and may have been stolen or sold. The specimen is missing its head and tail, although the rest of the skeleton is mostly intact.[29] It takes its name from the Maxberg Museum, where it was exhibited for a number of years.[30]

The Archaeopteryx specimen is, as of 2011, one of only 11 body fossils ever found,[31] but has been missing since the death of its last known owner, Eduard Opitsch, in 1991.[29] It is conventionally referred to as the third specimen.

History

Discovery and the first owner

.jpg)

The Maxberg specimen was discovered in 1956 by two workers, Ernst Fleisch and Karl Hinterholzinger, in a quarry between Solnhofen and Langenaltheim, Bavaria, eight decades after the previous discovery in 1874/1875, the Berlin specimen.[32] The workers however did not recognise the significance of the find, mistaking it for an unimportant crayfish, Mecochirus longimanatus, and the pieces remained stored in a hut for the following two years.[29]

In 1958, Eduard Opitsch, owner of the quarry, allowed the fossil to be taken away by visiting geologist Klaus Fesefeldt who believed it was some vertebrate and sent it to the University of Erlangen where paleontologist Professor Florian Heller identified it correctly and further prepared it.[33] Opitsch, described by contemporaries as having had a difficult personality, attempted to sell the specimen to the highest bidder remarking: "if such things are found only once every hundred years, nothing will be given away for free". The Freie Universität Berlin offered 30,000 Deutschmark; in response the Bavarian institutions tried to preserve the specimen for their own Bundesland by outbidding them. In negotiations with Princess Therese zu Oettingen-Spielberg of the Bayerische Staatssamlung für Paläontologie und Geologie Opitsch, though never demanding an exact amount, had already vaguely indicated a price of about 40,000 DM. The BSP was willing to pay this but hesitant to compensate for the fact that any sum would be taxed at 40% as company profits. The tax collectors did not allow an exemption to be made for this special case. As a result an irritated Opitsch in August 1965 suddenly broke off negotiations and declined all further offers.[29]

Display and withdrawal

For a number of years, the find was displayed at the local Maxberg Museum. In 1974 Opitsch allowed high-quality casts to be made on the occasion of an exhibition by the Senckenberg Museum dedicated to Archaeopteryx, but immediately afterwards he removed it from public display altogether. Instead, he stored it in his private residence in nearby Pappenheim declining access to the specimen to all scientists.[29] He rejected a proposal to further prepare the slabs.

Opitsch had become more defensive about the fossil after an announcement of another specimen in 1973. This was the Eichstätt specimen, which was much more complete and also transpired to have already been discovered in 1951, five years before the Maxberg. He felt that the large attention for this new specimen was intended to deprecate his own. Attempts were made to gain permission to show the specimen in exhibitions, but Opitsch always refused the requests.[30] In 1984 Peter Wellnhofer, a renowned expert on Archaeopteryx, attempted to gather together all specimens and experts on the subject in Eichstätt but Opitsch ignored his request and the conference proceeded without the Maxberg specimen[34] — the London and Berlin specimens however were absent too, the former because seen as too valuable by the British Museum of Natural History, the latter as it was about to be displayed in a surprise exhibition in Tokyo, together with a visit of the Berlin Brachiosaurus to Japan.

Disappearance

When Eduard Opitsch died in February 1991, the Maxberg specimen was not found in his house by his only heir, a nephew entering the building a few weeks after the death of his uncle who was the sole inhabitant.[35] Witnesses claim to have seen the specimen stored under his bed shortly before he died. Opitsch's marble headstone at the cemetery of Langenaltheim depicts a gilded engraving modelled after the specimen, which led to the rumour that he had taken it to his grave.[29] Another theory is that the specimen was sold secretly.[36] The case of the lost specimen was even investigated by the Bavarian police after the heir reported it stolen in July 1991, but no further evidence of its whereabouts was found.[30] Raimund Albersdörfer, a German fossil dealer who was involved in the 2009 purchase of the long-missing Daiting Specimen, believes, as do others, that the specimen is not lost but rather in private possession and will resurface eventually.[29] As a result of all this, the specimen has no official inventory number.

The disappearance of the Maxberg specimen has led to renewed calls to protect fossil finds by law. The laws in this regard would be a matter of the federal states in Germany. Bavaria, to this date, is the only Bundesland having no laws protecting such finds.[29] However, the federal government has declared the Maxberg specimen a national cultural heritage, national wertvolles Kulturgut, in 1995, meaning it cannot be exported without permission.

In 2009, the value of a high-quality Archaeopteryx specimen was estimated to be in excess of three million Euro.[29]

Specimen

The Maxberg specimen, like all Archaeopteryx exemplars except the so-called "Daiting", shows body feathers.[37] The specimen was formally described in 1959 by Florian Heller.[32] Heller had roentgen and UV-pictures made by the photographic institute of Wilhelm Stürmer.[38] The specimen consists of a slab and counterslab, mainly showing a torso with some feather impressions, lacking both head and tail.[39] The roentgen pictures proved that parts of the skeleton still remained hidden inside the stone.[40] The fossil was studied for a time by researchers before Opitsch removed it from public exhibition, among them John Ostrom.[41]

It was determined by a geologist that the quarry that produced the Maxberg specimen had also produced the London specimen, which was found almost one hundred years earlier, in 1861. However, the Maxberg example was found almost seven metres lower than the London one.[39]

The Haarlem specimen

The Haarlem Specimen (TM 6428, also known as the Teyler Specimen) was discovered in 1855 near Riedenburg, Germany and described as a Pterodactylus crassipes in 1857 by von Meyer. It was reclassified in 1970 by John Ostrom and is currently located at the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, the Netherlands. It was the very first specimen, despite the classification error. It is also one of the least complete specimens, consisting mostly of limb bones and isolated cervical vertebrae and ribs.[1]

The Eichstätt specimen

.jpg)

The Eichstätt Specimen (JM 2257) was discovered in 1951 near Workerszell, Germany and described by Peter Wellnhofer in 1974. Currently located at the Jura Museum in Eichstätt, Germany, it is the smallest specimen and has the second best head. It is possibly a separate genus (Jurapteryx recurva) or species (A. recurva).[1]

The Solnhofen specimen

The Solnhofen Specimen (BSP 1999) was discovered in the 1970s near Eichstätt, Germany and described in 1988 by Wellnhofer. Currently located at the Bürgermeister-Müller-Museum in Solnhofen, it was originally classified as Compsognathus by an amateur collector, the same burgomaster Friedrich Müller after which the museum is named. It is the largest specimen known and may belong to a separate genus and species, Wellnhoferia grandis. It is missing only portions of the neck, tail, backbone, and head.[1]

The Munich specimen

The Munich Specimen (S6, formerly known as the Solnhofen-Aktien-Verein Specimen) was discovered on 3 August 1992 near Langenaltheim and described in 1993 by Wellnhofer. It is currently located at the Paläontologisches Museum München in Munich, to which it was sold in 1999 for 1.9 million Deutschmark. What was initially believed to be a bony sternum turned out to be part of the coracoid,[42] but a cartilaginous sternum may have been present. Only the front of its face is missing. It may be a new species, A. bavarica.

The Daiting specimen

.jpg)

An eighth, fragmentary specimen was discovered in 1990, not in Solnhofen limestone, but in somewhat younger sediments at Daiting, Suevia. It is therefore known as the Daiting Specimen, and had been known since 1996 only from a cast, briefly shown at the Naturkundemuseum in Bamberg. Long remaining hidden and therefore dubbed the 'Phantom', the original was purchased by palaeontologist Raimund Albertsdörfer in 2009.[43] It was on display for the first time with six other original fossils of Archaeopteryx at the Munich Mineral Show in October 2009.[44] A first, quick look by scientists indicates that this specimen might represent a new species of Archaeopteryx.[45] It was found in a limestone bed that was a few hundred thousand years younger than the other finds.[43]

The Bürgermeister-Müller specimen

.jpg)

Another fragmentary fossil was found in 2000. It is in private possession and since 2004 on loan to the Bürgermeister-Müller Museum in Solenhofen, so it is called the Bürgermeister-Müller Specimen; the institute itself officially refers to it as the "Exemplar of the families Ottman & Steil, Solnhofen". As the fragment represents the remains of a single wing of Archaeopteryx, the popular name of this fossil is "chicken wing".[1]

The Thermopolis specimen

Long in a private collection in Switzerland, the Thermopolis Specimen (WDC CSG 100) was discovered in Bavaria and described in 2005 by Mayr, Pohl, and Peters. Donated to the Wyoming Dinosaur Center in Thermopolis, Wyoming, it has the best-preserved head and feet; most of the neck and the lower jaw have not been preserved. The "Thermopolis" specimen was described in the December 2, 2005 Science journal article as "A well-preserved Archaeopteryx specimen with theropod features"; it shows that the Archaeopteryx lacked a reversed toe — a universal feature of birds — limiting its ability to perch on branches and implying a terrestrial or trunk-climbing lifestyle.[46] This has been interpreted as evidence of theropod ancestry. In 1988, Gregory S. Paul claimed to have found evidence of a hyperextensible second toe, but this was not verified and accepted by other scientists until the Thermopolis specimen was described.[47] "Until now, the feature was thought to belong only to the species' close relatives, the deinonychosaurs."[48]

The Thermopolis Specimen was assigned to Archaeopteryx siemensii in 2007. The specimen itself, currently on loan to the Royal Tyrrell Museum, Drumheller, Alberta, Canada, is considered the most complete and well preserved Archaeopteryx remains yet.[49]

The eleventh specimen

In 2011 the discovery of an eleventh specimen was announced. It is said to be one of the more complete specimens, but is missing the skull and one forelimb. It is privately owned and has yet to be given a name or described scientifically.[50][51]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 Wellnhofer, Peter (2009). Archaeopteryx: The Icon of Evolution. Munich: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. ISBN 978-3-89937 Check

|isbn=value (help). - ↑ 2.0 2.1

- ↑ National Geographic News- Earliest Bird Had Feet Like Dinosaur, Fossil Shows - Nicholas Bakalar, December 1, 2005, Page 1. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Griffiths, P. J. (1996). "The Isolated Archaeopteryx Feather". Archaeopteryx 14: 1–26.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Meyer, H. v. Archaeopteryx lithographica (Vogel-Feder) und Pterodactylus von Solnhofen. (Letter to Prof. Bronn of September 30, 1861). Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognoisie, Geologie und Petrefakten-Kunde 1861: 678-679; Stuttgart.

- ↑ Meyer, H. v. Archaeopteryx lithographica aus dem lithographischen Schiefer von Solenhofen. Palaeontolographica 10 (2nd part in April, 1862): 53-56; Cassel.

- ↑ Ji Q, P.J. Currie, M.A. Norell & S.A. Ji. 1998. Two feathered dinosaurs from northeastern China. Nature 393: 753-761.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Conference references: R. Carney, et al. 2011. Black Feather Colour in Archaeopteryx. 2011 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Annual Meeting Abstracts, p 84

- ↑ Griffiths, P.J. 1996. The isolated Archaeopteryx feather. Archaeopteryx 14: 1-26; Eichstätt.

- ↑ Feduccia, A. & H. B. Tordoff 1979. Feathers of Archaeopteryx: asymmetric vanes indicate aerodynamic function. Science 203: 1021-1022.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Speakman, J.R. & S.C. Thomson 1994. Flight capabilities of Archaeopteryx. Nature 370: 514; London.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Tischlinger, H. & D. M. Unwin 2004. UV-Untersuchungen des Berliner Exemplares von Archaeopteryx lithographica H. v. Meyer 1861 und der isolierten Archaeopteryx-Feder. Archaeopteryx 22: 17-50; Eichstätt.

- ↑ Switek, Brian (9 November 2011), "Archaeopteryx was robed in black", New Scientist (Las Vegas)

- ↑ Billy, C. & A. Cailleux 1969. Dendrites de manganèse et bactéries. Science Progrès Découverte 3414: 381-385; Paris.

- ↑ Davis, P.G. & D.E.G. Briggs 1995. Fossilization of feathers. GEology 23(9): 783-786.

- ↑ British Museum of Natural History - 'BMNH 37001' - the type specimen

- ↑ Chiappe, Luis M. (2007). Glorified Dinosaurs. Sydney: UNSW Press. pp. 118–146. ISBN 0-471-24723-5.

- ↑ Darwin, Origin of Species, Chapter 9, p. 367

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species. John Murray.. Please note Darwin's spelling: 'Archeopteryx', not 'Archaeopteryx'.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Witte, F.E. 1863. Die Archaeopteryx lithographica. (Letter to Prof. H.B. Geinitz). - Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geologie und Palaeontologie 1863: 567-568; Stuttgart.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Wager, A. 1862. On a new Fossil Reptile supposed to be furnished with Feathers. -Annals and Magazine of Natural HIstory (3)9: 261-267; London.

- ↑ Häberlein, E. German Letter of March 21, 1862.

- ↑ Häberlein, E. German Letter of May 29, 1862.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Beer, G. de 1954. Archaeopteryx lithographica. A study based upon the British Museum specimen. - pp. I-XI, 1-68; London.

- ↑ Häberlein, E. German Letter of August 6, 1862.

- ↑ Weinland, D. F. 1863. Der Greif von Solenhofen (Archaeopteryx lithographica H. v. Meyer). - Der Zoologische Garten 4(6): 118-122; Frankfurt a.M.

- ↑ Rolfe, W. D. Jan, A. C. Milner & F. G. Hay 1988. The Price of Fossils. - Special Papers in Palaeontology 40(1988): 139-171; London.

- ↑ Elżanowski A. (2002): Archaeopterygidae (Upper Jurassic of Germany). In: Chiappe, L. M. & Witmer, L. M (eds.), Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs: 129–159. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 29.8 Sammler und Forscher - ein schwieriges Verhältnis (German) Sueddeutsche Zeitung - Collectors and scientists, a difficult relationship, published: 25 October 2009, accessed: 1 March 2011

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Archaeopteryx (German) www.fossilien-solnhofen.de, accessed: 1 March 2011

- ↑ Stelldichein der Urvögel (German) Sueddeutsche Zeitung - Meeting of the Urvogel, published: 25 October 2009, accessed: 1 March 2011

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Dingus, Rowe, 119

- ↑ Heller, F. (1960). "Der dritte Archaeopteryx-Fund aus den Solnhofener Plattenkalken des oberen Malm Frankens". Journal für Ornithologie 101: 7–28.

- ↑ Dingus, Rowe, 121

- ↑ Abbott, A. (1992). "Archaeopteryx fossil disappears from private collection". Nature 357: 6.

- ↑ All About Archaeopteryx talk.origins, accessed: 1 March 2011

- ↑ Four-winged birds may have been first fliers New Scientist, published: 23 May 2004, accessed: 1 March 2011

- ↑ Heller, F. (1959). "Ein dritter Archaeopteryx-Fund aus den Solnhofener Plattenkalken von Longenaltheim/Mfr". Erlanger Geologische Abhandlungen 31: 1–25.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Archaeopteryx www.stonecompany.com, accessed: 1 March 2011

- ↑ Heller, F.; Stürmer, W. (1960). "Der Dritte Archaeopteryx-Fund". Natur und Volk 90 (5): 137–145.

- ↑ Dingus, Rowe, 120

- ↑ Wellnhofer, P. & Tischlinger, H. (2004). Das "Brustbein" von Archaeopteryx bavarica Wellnhofer 1993 - eine Revision. Archaeopteryx. 22: 3–15. [Article in German]

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Archäologischer Sensationsfund in Daiting, (German) Augsburger Allgemeine - Donauwörth edition, published: 28 November 2009, accessed: 23 December 2009

- ↑ Sammler und Forscher - ein schwieriges Verhältnis (German), Sueddeutsche Zeitung, published: 25 October 2009, accessed: 25 December 2009

- ↑ Wiedergefundener Archaeopteryx ist wohl neue Art (German) Die Zeit, accessed: 25 December 2009

- ↑ Mayr, G; Pohl, B; Peters, DS. (2005). "A well-preserved Archaeopteryx specimen with theropod features". Science 310 (5753): 1483–1486. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1483M. doi:10.1126/science.1120331. PMID 16322455. See commentary on article

- ↑ Paul, G.S. (1988). Predatory Dinosaurs of the World, a Complete Illustrated Guide. New York: Simon and Schuster. 464 p.

- ↑ National Geographic News- Earliest Bird Had Feet Like Dinosaur, Fossil Shows - Nicholas Bakalar, December 1, 2005, Page 2. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- ↑ Mayr, G.; Phol, B.; Hartman, S.; Peters, D.S. (2007). "The tenth skeletal specimen of Archaeopteryx". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 149: 97–116. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00245.x.

- ↑ Switek, Brian (October 19, 2011), Paleontologists Unveil the 11th Archaeopteryx, Smithsonian.com Dinosaur Tracking blog

- ↑ Hecht, Jeff (October 20, 2011), Another stunning Archaeopteryx fossil found in Germany, New Scientist, Short Sharp Science blog