Specific gravity

| | |

| Common symbol(s): | SG |

| SI unit: | N/A (unitless) |

| Derivations from other quantities: |  |

- This page is about the measurement using water as a reference. For a general use of specific gravity, see relative density. See intensive property for the property implied by specific.

_3rd_Class_Rolando_Calilung_tests_for_a_specific_gravity_test_on_JP-5_fuel.jpg)

Specific gravity is the ratio of the density of a substance to the density (mass of the same unit volume) of a reference substance. Apparent specific gravity is the ratio of the weight of a volume of the substance to the weight of an equal volume of the reference substance. The reference substance is nearly always water for liquids or air for gases. Temperature and pressure must be specified for both the sample and the reference. Pressure is nearly always 1 atm equal to 101.325 kPa. Temperatures for both sample and reference vary from industry to industry. In British brewing practice the specific gravity as specified above is multiplied by 1000.[1] Specific gravity is commonly used in industry as a simple means of obtaining information about the concentration of solutions of various materials such as brines, hydrocarbons, sugar solutions (syrups, juices, honeys, brewers wort, must etc.) and acids.

Details

Specific gravity, as it is a ratio of densities, is a dimensionless quantity. Specific gravity varies with temperature and pressure; reference and sample must be compared at the same temperature and pressure, or corrected to a standard reference temperature and pressure. Substances with a specific gravity of 1 are neutrally buoyant in water, those with SG greater than one are denser than water, and so (ignoring surface tension effects) will sink in it, and those with an SG of less than one are less dense than water, and so will float. In scientific work the relationship of mass to volume is usually expressed directly in terms of the density (mass per unit volume) of the substance under study. It is in industry where specific gravity finds wide application, often for historical reasons.

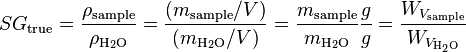

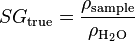

True specific gravity can be expressed mathematically as:

where  is the density of the sample and

is the density of the sample and  is the density of water.

is the density of water.

The apparent specific gravity is simply the ratio of the weights of equal volumes of sample and water in air:

where  represents the weight of sample and

represents the weight of sample and  the weight of water, both measured in air.

the weight of water, both measured in air.

It can be shown that true specific gravity can be computed from different properties:

where  is the local acceleration due to gravity,

is the local acceleration due to gravity,  is the volume of the sample and of water (the same for both),

is the volume of the sample and of water (the same for both),  is the density of the sample,

is the density of the sample,  is the density of water and

is the density of water and  represents a weight obtained in vacuum.

represents a weight obtained in vacuum.

The density of water varies with temperature and pressure as does the density of the sample so that it is necessary to specify the temperatures and pressures at which the densities or weights were determined. It is nearly always the case that measurements are made at nominally 1 atmosphere (1013.25 mbar ± the variations caused by changing weather patterns) but as specific gravity usually refers to highly incompressible aqueous solutions or other incompressible substances (such as petroleum products) variations in density caused by pressure are usually neglected at least where apparent specific gravity is being measured. For true (in vacuo) specific gravity calculations air pressure must be considered (see below). Temperatures are specified by the notation  with

with  representing the temperature at which the sample's density was determined and

representing the temperature at which the sample's density was determined and  the temperature at which the reference (water) density is specified. For example SG (20°C/4°C) would be understood to mean that the density of the sample was determined at 20 °C and of the water at 4°C. Taking into account different sample and reference temperatures we note that while

the temperature at which the reference (water) density is specified. For example SG (20°C/4°C) would be understood to mean that the density of the sample was determined at 20 °C and of the water at 4°C. Taking into account different sample and reference temperatures we note that while  (20°C/20°C) it is also the case that

(20°C/20°C) it is also the case that  (20°C/4°C). Here temperature is being specified using the current ITS-90 scale and the densities[2] used here and in the rest of this article are based on that scale. On the previous IPTS-68 scale the densities at 20 °C and 4 °C are, respectively, 0.9982071 and 0.9999720 resulting in an SG (20°C/4°C) value for water of 0.9982343.

(20°C/4°C). Here temperature is being specified using the current ITS-90 scale and the densities[2] used here and in the rest of this article are based on that scale. On the previous IPTS-68 scale the densities at 20 °C and 4 °C are, respectively, 0.9982071 and 0.9999720 resulting in an SG (20°C/4°C) value for water of 0.9982343.

As the principal use of specific gravity measurements in industry is determination of the concentrations of substances in aqueous solutions and these are found in tables of SG vs concentration it is extremely important that the analyst enter the table with the correct form of specific gravity. For example, in the brewing industry, the Plato table, which lists sucrose concentration by weight against true SG, were originally (20°C/4°C)[3] i.e. based on measurements of the density of sucrose solutions made at laboratory temperature (20 °C) but referenced to the density of water at 4 °C which is very close to the temperature at which water has its maximum density of  equal to 0.999972 g·cm−3 in SI units (or 62.43 lbm·ft−3 in United States customary units). The ASBC table[4] in use today in North America, while it is derived from the original Plato table is for apparent specific gravity measurements at (20°C/20°C) on the IPTS-68 scale where the density of water is 0.9982071 g·cm−3. In the sugar, soft drink, honey, fruit juice and related industries sucrose concentration by weight is taken from a table prepared by A. Brix which uses SG (17.5°C/17.5°C). As a final example, the British SG units are based on reference and sample temperatures of 60F and are thus (15.56°C/15.56°C).

equal to 0.999972 g·cm−3 in SI units (or 62.43 lbm·ft−3 in United States customary units). The ASBC table[4] in use today in North America, while it is derived from the original Plato table is for apparent specific gravity measurements at (20°C/20°C) on the IPTS-68 scale where the density of water is 0.9982071 g·cm−3. In the sugar, soft drink, honey, fruit juice and related industries sucrose concentration by weight is taken from a table prepared by A. Brix which uses SG (17.5°C/17.5°C). As a final example, the British SG units are based on reference and sample temperatures of 60F and are thus (15.56°C/15.56°C).

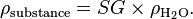

Given the specific gravity of a substance, its actual density can be calculated by rearranging the above formula:

Occasionally a reference substance other than water is specified (for example, air), in which case specific gravity means density relative to that reference.

Measurement: apparent and true specific gravity

Pycnometer

Specific gravity can be measured in a number of ways. The following illustration involving the use of the pycnometer is instructive. A pycnometer is simply a bottle which can be precisely filled to a specific, but not necessarily accurately known volume,  . Placed upon a balance of some sort it will exert a force .

. Placed upon a balance of some sort it will exert a force .

where  is the mass of the bottle and

is the mass of the bottle and  the gravitational acceleration at the location at which the measurements are being made.

the gravitational acceleration at the location at which the measurements are being made.  is the density of the air at the ambient pressure and

is the density of the air at the ambient pressure and  is the density of the material of which the bottle is made (usually glass) so that the second term is the mass of air displaced by the glass of the bottle whose weight, by Archimedes Principle must be subtracted. The bottle is, of course, filled with air but as that air displaces an equal amount of air the weight of that air is canceled by the weight of the air displaced. Now we fill the bottle with the reference fluid e.g. pure water. The force exerted on the pan of the balance becomes:

is the density of the material of which the bottle is made (usually glass) so that the second term is the mass of air displaced by the glass of the bottle whose weight, by Archimedes Principle must be subtracted. The bottle is, of course, filled with air but as that air displaces an equal amount of air the weight of that air is canceled by the weight of the air displaced. Now we fill the bottle with the reference fluid e.g. pure water. The force exerted on the pan of the balance becomes:

If we subtract the force measured on the empty bottle from this (or tare the balance before making the water measurement) we obtain.

where the subscript n indicated that this force is net of the force of the empty bottle. The bottle is now emptied, thoroughly dried and refilled with the sample. The force, net of the empty bottle, is now:

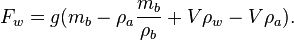

where  is the density of the sample. The ratio of the sample and water forces is:

is the density of the sample. The ratio of the sample and water forces is:

This is called the Apparent Specific Gravity, denoted by subscript A, because it is what we would obtain if we took the ratio of net weighings in air from an analytical balance or used a hydrometer (the stem displaces air). Note that the result does not depend on the calibration of the balance. The only requirement on it is that it read linearly with force. Nor does  depend on the actual volume of the pycnometer.

depend on the actual volume of the pycnometer.

Further manipulation and finally substitution of  ,the true specific gravity,(the subscript V is used because this is often referred to as the specific gravity in vacuo) for

,the true specific gravity,(the subscript V is used because this is often referred to as the specific gravity in vacuo) for  gives the relationship between apparent and true specific gravity.

gives the relationship between apparent and true specific gravity.

In the usual case we will have measured weights and want the true specific gravity. This is found from

Since the density of dry air at 1013.25 mb at 20 °C is[5] 0.001205 g·cm−3 and that of water is 0.998203 g·cm−3 the difference between true and apparent specific gravities for a substance with specific gravity (20°C/20°C) of about 1.100 would be 0.000120. Where the specific gravity of the sample is close to that of water (for example dilute ethanol solutions) the correction is even smaller.

Digital density meters

Hydrostatic Pressure-based Instruments: This technology relies upon Pascal's Principle which states that the pressure difference between two points within a vertical column of fluid is dependent upon the vertical distance between the two points, the density of the fluid and the gravitational force. This technology is often used for tank gauging applications as a convenient means of liquid level and density measure.

Vibrating Element Transducers: This type of instrument requires a vibrating element to be placed in contact with the fluid of interest. The resonant frequency of the element is measured and is related to the density of the fluid by a characterization that is dependent upon the design of the element. In modern laboratories precise measurements of specific gravity are made using oscillating U-tube meters. These are capable of measurement to 5 to 6 places beyond the decimal point and are used in the brewing, distilling, pharmaceutical, petroleum and other industries. The instruments measure the actual mass of fluid contained in a fixed volume at temperatures between 0 and 80 °C but as they are microprocessor based can calculate apparent or true specific gravity and contain tables relating these to the strengths of common acids, sugar solutions, etc. The vibrating fork immersion probe is another good example of this technology. This technology also includes many coriolis-type mass flow meters which are widely used in chemical and petroleum industry for high accuracy mass flow measurement and can be configured to also output density information based on the resonant frequency of the vibrating flow tubes.

Ultrasonic Transducer: Ultrasonic waves are passed from a source, through the fluid of interest, and into a detector which measures the acoustic spectroscopy of the waves. Fluid properties such as density and viscosity can be inferred from the spectrum.

Radiation-based Gauge: Radiation is passed from a source, through the fluid of interest, and into a scintillation detector, or counter. As the fluid density increases, the detected radiation "counts" will decrease. The source is typically the radioactive isotope cesium-137, with a half-life of about 30 years. A key advantage for this technology is that the instrument is not required to be in contact with the fluid – typically the source and detector are mounted on the outside of tanks or piping. .[6]

Buoyant Force Transducer: the buoyancy force produced by a float in a homogeneous liquid is equal to the weight of the liquid that is displaced by the float. Since buoyancy force is linear with respect to the density of the liquid within which the float is submerged, the measure of the buoyancy force yields a measure of the density of the liquid. One commercially available unit claims the instrument is capable of measuring specific gravity with an accuracy of +/- 0.005 SG units. The submersible probe head contains a mathematically characterized spring-float system. When the head is immersed vertically in the liquid, the float moves vertically and the position of the float controls the position of a permanent magnet whose displacement is sensed by a concentric array of Hall-effect linear displacement sensors. The output signals of the sensors are mixed in a dedicated electronics module that provides an output voltage whose magnitude is a direct linear measure of the quantity to be measured.[7]

In-Line Continuous Measurement: Slurry is weighed as it travels through the metered section of pipe using a patented, high resolution load cell. This section of pipe is of optimal length such that a truly representative mass of the slurry may be determined. This representative mass is then interrogated by the load cell 110 times per second to ensure accurate and repeatable measurement of the slurry.[citation needed]

Examples

- Helium gas has a density of 0.164g/liter[8] It is 0.139 times as dense as air.

- Air has a density of 1.18g/l[8]

| Material | Specific Gravity |

|---|---|

| Balsa wood | 0.2 |

| Oak wood | 0.75 |

| Ethanol | 0.78 |

| Water | 1 |

| Table salt | 2.17 |

| Aluminium | 2.7 |

| Iron | 7.87 |

| Copper | 8.96 |

| Lead | 11.35 |

| Mercury | 13.56 |

| Depleted uranium | 19.1 |

| Gold | 19.3 |

| Osmium | 22.59 |

(Samples may vary, and these figures are approximate.)

- Urine normally has a specific gravity between 1.003 and 1.035.

- Blood normally has a specific gravity of ~1.060.

See also

- API gravity

- Baumé scale

- Buoyancy

- Fluid mechanics

- Gravity (beer)

- Hydrometer

- Jolly balance

- Pycnometer

- Plato scale

References

- ↑ Hough, J.S., Briggs, D.E., Stevens, R and Young, T.W. Malting and Brewing Science, Vol. II Hopped Wort and Beer, Chapman and Hall, London, 1991, p. 881

- ↑ Bettin, H.; Spieweck, F.: "Die Dichte des Wassers als Funktion der Temperatur nach Einführung des Internationalen Temperaturskala von 1990" PTB-Mitteilungen 100 (1990) pp. 195–196

- ↑ ASBC Methods of Analysis Preface to Table 1: Extract in Wort and Beer, American Society of Brewing Chemists, St Paul, 2009

- ↑ ASBC Methods of Analysis op. cit. Table 1: Extract in Wort and Beer

- ↑ DIN51 757 (04.1994): Testing of mineral oils and related materials; determination of density

- ↑ Density – VEGA Americas, Inc. Ohmartvega.com. Retrieved on 2011-11-18.

- ↑ Process Control Digital Electronic Hydrometer. Gardco. Retrieved on 2011-11-18.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 UCSB

| |||||