Spatial frequency

In mathematics, physics, and engineering, spatial frequency is a characteristic of any structure that is periodic across position in space. The spatial frequency is a measure of how often sinusoidal components (as determined by the Fourier transform) of the structure repeat per unit of distance. The SI unit of spatial frequency is cycles per meter. In image-processing applications, spatial frequency is often expressed in units of cycles per millimeter or equivalently line pairs per millimeter.

In wave mechanics, the spatial frequency is commonly denoted by  [1]

or sometimes

[1]

or sometimes  , although the latter is also used[2]

to represent temporal frequency. It is related to the wavelength

, although the latter is also used[2]

to represent temporal frequency. It is related to the wavelength  by the formula

by the formula

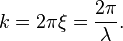

Likewise, the angular wave number  , measured in radians per meter, is related to spatial frequency and wavelength by

, measured in radians per meter, is related to spatial frequency and wavelength by

Visual perception

In the study of visual perception, sinusoidal gratings are frequently used to probe the capabilities of the visual system. In these stimuli, spatial frequency is expressed as the number of cycles per degree of visual angle. Sine-wave gratings also differ from one another in amplitude (the magnitude of difference in intensity between light and dark stripes), and angle.

Spatial-frequency theory

The spatial-frequency theory refers to the theory that the visual cortex operates on a code of spatial frequency, not on the code of straight edges and lines hypothesised by Hubel and Wiesel.[3][4] In support of this theory is the experimental observation that the visual cortex neurons respond even more robustly to sine-wave gratings that are placed at specific angles in their receptive fields than they do to edges or bars. Most neurons in the primary visual cortex respond best when a sine-wave grating of a particular frequency is presented at a particular angle in a particular location in the visual field [5]

The spatial-frequency theory of vision is based on two physical principles:

- Any visual stimulus can be represented by plotting the intensity of the light along lines running through it.

- Any curve can be broken down into constituent sine waves by Fourier analysis.

The theory states that in each functional module of the visual cortex, Fourier analysis is performed on the receptive field and the neurons in each module are thought to respond selectively to various orientations and frequencies of sine wave gratings. When all of the visual cortex neurons that are influenced by a specific scene respond together, the perception of the scene is created by the summation of the various sine-wave gratings. One is generally not aware of the individual spatial frequency components since all of the elements are essentially blended together into one smooth representation. However, computer-based filtering procedures can be used to deconstruct an image into its individual spatial frequency components.[6] Research on spatial frequency detection by visual neurons complements and extends previous research using straight edges rather than refuting it.[7]

Further research shows that different spatial frequencies convey different information about the appearance of a stimulus. High spatial frequencies represent abrupt spatial changes in the image, such as edges, and generally correspond to featural information and fine detail. Low spatial frequencies, on the other hand, represent global information about the shape, such as general orientation and proportions.[8] Rapid and specialised perception of faces is known to rely more on low spatial frequency information. [9] In the general population of adults, the threshold for spatial frequency discrimination is about 7%. It is often poorer in dyslexic individuals.[10]

Sinusoidal gratings and Michelson equation

There is an important quantitative concept related to spatial frequency, known as the Michelson equation:

In layman's terms, this is the ratio of the crest-trough distance to the maximum thereof, which is twice the average. One degree on the visual field represents four cycles on the wave pattern.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ SPIE Optipedia article: "Spatial Frequency"

- ↑ As in e.g. Planck's formula.

- ↑ Martinez, L. M., & ALonzo, J. M. (2203). Complex receptive fields in primary visual cortex. The Neuroscientist, 9, 317-331

- ↑ De Valois, R. L., & De Valois, K. K. (1988). Spatial vision. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Issa, N. P., Trepel, C., & Stryker, M. P. (2000). Spatial frequency maps in cat visual cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 20, 8504-8514

- ↑ Blake, R. and Sekuler, R., Perception, 3rd ed. Chapter 3. ISBN 978-0072887600

- ↑ Pinel, J. P. J., Biopsychology, 6th ed. 293-294. ISBN 0-205-42651-4

- ↑ Bar M (Aug 2004). "Visual objects in context". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5 (8): 617–29. doi:10.1038/nrn1476. PMID 15263892. "

Box 2: Spatial frequencies and the information they convey" - ↑ Awasthi B, Friedman J, Williams, MA (2011). "Faster, stronger, lateralized: Low spatial frequency information supports face processing". Neuropsychologia 49 (13): 3583–3590. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.08.027.

- ↑ Ben-Yehudah G, Ahissar M (May 2004). "Sequential spatial frequency discrimination is consistently impaired among adult dyslexics". Vision Res. 44 (10): 1047–63. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2003.12.001. PMID 15031099.

- ↑ "Vision" McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology, vol. 19, p.292 1997

External links

- "Tutorial: Spatial Frequency of an Image". Hakan Haberdar, University of Houston. Retrieved March 2012.

- Kalloniatis, Michael; Luu, Charles (2007). "Webvision: Part IX Psychophysics of Vision. 2 Visual Acuity, Contrast Sensitivity". University of Utah. Retrieved July 2009.