South Pacific (musical)

| South Pacific | |

|---|---|

Original Playbill cover: Martin and Pinza | |

| Music | Richard Rodgers |

| Lyrics | Oscar Hammerstein II |

| Book |

Oscar Hammerstein II Joshua Logan |

| Basis |

Tales of the South Pacific by James A. Michener |

| Productions |

1949 Broadway 1950 U.S. tour 1951 West End 1988 West End revival 2001 West End revival 2007 U.K. tour 2008 Broadway revival 2009 U.S. tour |

| Awards |

Pulitzer Prize for Drama Tony Award for Best Musical Tony Award for Best Original Score Tony Award for Best Author Tony Award for Best Revival of a Musical |

South Pacific is a musical composed by Richard Rodgers, with lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II and book by Hammerstein and Joshua Logan. The work premiered in 1949 on Broadway and was an immediate hit, running for 1,925 performances. The story is based on James A. Michener's Pulitzer Prize-winning 1947 book Tales of the South Pacific, combining elements of several of the stories. Rodgers and Hammerstein believed that they could write a musical based on Michener's work that would be financially successful and, at the same time, would send a strong progressive message on racism.

The plot centers on an American nurse stationed on a South Pacific island during World War II who falls in love with a middle-aged expatriate French plantation owner but struggles to accept his mixed-race children. A secondary romance, between a U.S. lieutenant and a young Tonkinese woman, explores his fears of the social consequences should he marry his Asian sweetheart. The issue of racial prejudice is candidly explored throughout the musical, most controversially in the lieutenant's song, "You've Got to Be Carefully Taught". Supporting characters, including a comic petty officer and the Tonkinese girl's mother, help to tie the stories together. Because he lacked military knowledge, Hammerstein had difficulty writing that part of the script; the director of the original production, Logan, assisted him and received credit as co-writer of the book.

The original Broadway production enjoyed immense critical and box-office success, became the second-longest running Broadway musical to that point (behind Rodgers and Hammerstein's earlier Oklahoma!), and has remained popular ever since. After they signed Ezio Pinza and Mary Martin as the leads, Rodgers and Hammerstein wrote several of the songs with the particular talents of their stars in mind. The piece won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1950. Especially in the Southern U.S., its racial theme provoked controversy, for which its authors were unapologetic. Several of its songs, including "Bali Ha'i", "I'm Gonna Wash That Man Right Outa My Hair", "Some Enchanted Evening", "There Is Nothing Like a Dame", "Happy Talk", "Younger Than Springtime" and "I'm in Love with a Wonderful Guy", have become popular standards.

The production won ten Tony Awards, including Best Musical, Best Score and Best Libretto, and it is the only musical production to win Tony Awards in all four acting categories. Its original cast album was the bestselling record of the 1940s, and other recordings of the show have also been popular. The show has enjoyed many successful revivals and tours, spawning a 1958 film and television adaptations. The 2008 Broadway revival was a critical success, ran for 996 performances and won seven Tonys, including Best Musical Revival.

Background

Although book editor and university instructor James Michener could have avoided military service in World War II as a birthright Quaker, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy in October 1942. He was not sent to the South Pacific theater until April 1944, when he was assigned to write a history of the Navy in the Pacific and was allowed to travel widely. He survived a plane crash in New Caledonia; the near-death experience motivated him to write fiction, and he began listening to the stories told by soldiers. One journey took him to the Treasury Islands, where he discovered an unpleasant village populated by "scrawny residents and only one pig" called Bali-ha'i.[2] Struck by the name, Michener wrote it down and soon began to record his version of the tales on a battered typewriter.[3] On a plantation on the island of Espiritu Santo, he met a woman named Bloody Mary; she was small, almost toothless, her face stained with red betel juice. Punctuated with profanity learned from GIs, she complained endlessly to Michener about the French colonial government, which refused to allow her and other Tonkinese to return to their native Vietnam, lest the plantations be depopulated. She told him also of her plans to oppose colonialism in French Indochina.[n 1] These stories, collected into Tales of the South Pacific, won Michener the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for fiction.[3]

There are nineteen stories in Tales of the South Pacific. The stories stand independently but revolve around the preparation for an operation by the American military to dislodge the Japanese from a nearby island. This operation, dubbed Alligator, occurs in the penultimate story, "The Landing at Kuralei". Many of the characters die in that battle – the last story is called "The Cemetery at Huga Point." The stories are thematically linked in pairs: the first and final stories are reflective, the second and eighteenth involve battle, the third and seventeenth involve preparation for battle, a pattern which continues numerically. The tenth story, at the center, however, is not paired with any other. This story, "Fo' Dolla' ", was one of only four of his many works that Michener later admitted to holding in high regard. It was the one that attracted Rodgers and Hammerstein's attention for its potential to be converted into a stage work.[4]

"Fo' Dolla' ", set in part on the island of Bali-ha'i, focuses on the romance between a young Tonkinese woman, Liat, and one of the Americans, Marine Lieutenant Joe Cable, a Princeton graduate and scion of a wealthy Main Line family. Pressed to marry Liat by her mother, Bloody Mary, Cable reluctantly declines, realizing that the Asian girl would never be accepted by his family or Philadelphia society. He leaves for battle (where he will die) as Bloody Mary proceeds with her backup plan, to affiance Liat to a wealthy French planter on the islands. Cable struggles, during the story, with his own racism: he is able to overcome it sufficiently to love Liat, but not enough to take her home.[5]

Another source of the musical is the eighth story, "Our Heroine", which is thematically paired with the twelfth, "A Boar's Tooth", as both involve American encounters with local cultures. "Our Heroine" tells of the romance between Navy nurse Nellie Forbush, from rural Arkansas, and a wealthy, sophisticated planter, Frenchman Emile De Becque.[n 2] After falling in love with Emile, Nellie (who is introduced briefly in story #4, "An Officer and a Gentleman") learns that Emile has eight daughters, out of wedlock, with several local women. Michener tells us that "any person ... who was not white or yellow was a nigger" to Nellie, and while she is willing to accept two of the children (of French-Asian descent) who remain in Emile's household, she is taken aback by the other two girls who live there, evidence that the planter had cohabited with a darker Polynesian woman. To her great relief, she learns that this woman is dead, but Nellie endangers her relationship with Emile when she is initially unable to accept that Emile "had nigger children."[6] Nellie overcomes her feelings and returns to spend her life with her plantation owner.[7]

Additional elements of South Pacific had their genesis in others of Michener's nineteen tales. One introduces the character of Bloody Mary; another tells of a British spy hidden on the Japanese-controlled island who relays information about Japanese movements to Allied forces by radio. Michener based the spy, dubbed "the Remittance Man", on Captain Martin Clemens, a Scot, who unlike his fictional counterpart, survived the war. The stories also tell of the seemingly endless waiting that precedes battle, and the efforts of the Americans to repel boredom, which would inspire the song "There Is Nothing Like a Dame".[8] Several of the stories involve the Seabee, Luther Billis, who in the musical would be used for comic relief and also to tie together episodes involving otherwise unconnected characters.[9]

Creation

Inception

In the early 1940s, composer Richard Rodgers and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II, each a longtime Broadway veteran, joined forces and began their collaboration by writing two musicals that became massive hits, Oklahoma! (1943) and Carousel (1945).[10] An innovation for its time in integrating song, dialogue and dance, Oklahoma! would serve as "the model for Broadway shows for decades".[11] In 1999, Time magazine named Carousel the best musical of the century, writing that Rodgers and Hammerstein "set the standards for the 20th century musical".[12] Their next effort, Allegro (1947), was a comparative disappointment, running for less than a year, although it turned a small profit.[13] After this, the two were determined to achieve another hit.[14]

According to director Joshua Logan, a friend of both theatre men, he and Leland Hayward mentioned Michener's best-selling book to Rodgers as a possible basis for the duo's next play,[1] but the composer took no action. Logan recalled that he then pointed it out to Hammerstein, who read Michener's book and spoke to Rodgers; the two agreed to do the project so long as they had majority control, to which Hayward grudgingly agreed.[15] Michener, in his 1992 memoirs, however, wrote that the stories were first pitched as a movie concept to MGM by Kenneth MacKenna, head of the studio's literary department. MacKenna's half brother was Jo Mielziner, who had designed the sets for Carousel and Allegro. Michener states that Mielziner learned of the work from MacKenna and brought it to the attention of Hammerstein and Rodgers, pledging to create the sets if they took on the project.[16]

Hayward attempted to buy the rights from Michener outright, offering $500; Michener declined. Although playwright Lynn Riggs had received 1.5% of the box office grosses for the right to adapt Green Grow the Lilacs into Oklahoma!, Michener never regretted accepting one percent of the gross receipts from South Pacific. As Rodgers and Hammerstein began their work on the adaptation, Michener worked mostly with the lyricist, but Rodgers was concerned about the implications of the setting, fearing that he would have to include ukuleles and guitars, which he disliked. Michener assured him that the only instrument he had ever heard the natives play was an emptied barrel of gasoline, drummed upon with clubs.[17]

Composition

Soon after their purchase of the rights, Rodgers and Hammerstein decided not to include a ballet, as in their earlier works, feeling that the realism of the setting would not support one. Concerned that an adaptation too focused on "Fo' Dolla' ", the story of the encounter between Cable and Liat, would be too similar to Madama Butterfly, Hammerstein spent months studying the other stories and focused his attention on "Our Heroine", the tale of the romance between Nellie and Emile. The team decided to include both romances in the musical play. It was conventional at the time that if one love story in a musical was serious, the other would be more lighthearted, but in this case both were serious and focused on racial prejudice. They decided to increase the role played by Luther Billis in the stories, merging experiences and elements of several other characters into him. Billis's wheeling and dealing would provide comic relief.[18] They also shortened the title to South Pacific – Rodgers related that the producers tired of people making risqué puns on the word "tales".[19]

In early drafts of the musical, Hammerstein gave significant parts to two characters who eventually came to have only minor roles, Bill Harbison and Dinah Culbert. Harbison is one of the major characters in Tales of the South Pacific; a model officer at the start, he gradually degenerates to the point where, with battle imminent, he requests his influential father-in-law to procure for him a transfer to a post in the United States. Hammerstein conceived of him as a rival to Emile for Nellie's affections, and gave him a song, "The Bright Young Executive of Today". As redrafts focused the play on the two couples, Harbison became less essential, and he was relegated to a small role as the executive officer to the commander of the island, Captain Brackett. Dinah, a nurse and friend of Nellie, is also a major character in Michener's work, and was seen as a possible love interest for Billis, though any actual romance was limited by Navy regulations forbidding fraternization between officers (all American nurses in World War II were commissioned officers) and enlisted men. "I'm Gonna Wash That Man Right Outa My Hair" originated as a duet for Dinah and Nellie, with Dinah beginning the song and developing its theme.[20] According to Lovensheimer, Nellie's and Dinah's "friendship became increasingly incidental to the plot as the writing continued. Hammerstein eventually realized that the decision to wash Emile out of her hair had to be Nellie's. Only then did the scene have the dramatic potential for Nellie's emotional transition" as she realizes her love for Emile. In the final version, Dinah retains one solo line in the song.[21]

Joshua Logan, in his memoirs, stated that after months of effort in the first half of 1948, Hammerstein had written only the first scene, an outline, and some lyrics. Hammerstein was having trouble due to lack of knowledge of the military, a matter with which Logan, a veteran of the armed forces, was able to help. The dialogue was written in consultation between the two of them, and eventually Logan asked to be credited for his work. Rodgers and Hammerstein decided that while Logan would receive co-writing credit on the book, he would receive no author's royalties. Logan stated that a contract putting these changes into force was sent over to his lawyer with instructions that unless it was signed within two hours, Logan need not show up for rehearsals as director.[22] Logan signed, although his lawyer did not then tell him about the ultimatum.[23] Through the decades that followed, Logan brought the matter up from time to time, demanding compensation, but when he included his version of the events in his 1976 memoirs, it was disputed by Rodgers (Hammerstein had died in 1960).[23] Rodgers biographer Meryle Secrest suggests that Logan was compensated when South Pacific was filmed in 1958, as Logan received a substantial share of the profits as director.[n 3][24] According to Michener biographer Stephen J. May, "it is difficult to assess just how much of the final book Josh Logan was responsible for. Some estimates say 30 to 40 percent. But that percentage is not as critical perhaps as his knowledge of military lore and directing for the theatre, without which the creation of South Pacific would have collapsed during that summer of 1948."[25]

Rodgers composed the music once he received the lyrics from Hammerstein. A number of stories are told of the speed with which he wrote the music for South Pacific 's numbers. "Happy Talk" was said to have been composed in about twenty minutes; when Hammerstein, who had sent the lyrics by messenger, called to check whether Rodgers had received them, his partner informed him that he had both lyrics and music. Legend has it he composed "Bali Ha'i" in ten minutes over coffee in Logan's apartment; what he did create in that time frame was the three-note motif which begins both song and musical. Hammerstein's lyrics for "Bali Ha'i" were inspired by the stage backdrop which designer Jo Mielziner had painted. Feeling that the island of Bali Ha'i did not appear mysterious enough, Mielziner painted some mist near the summit of its volcano. When Hammerstein saw this he immediately thought of the lyric, "my head sticking up from a low-flying cloud" and the rest of the song followed easily from that.[26]

Casting and out-of-town previews

In May 1948, Rodgers received a telephone call from Edwin Lester of the Los Angeles Civic Light Opera. Lester had signed former Metropolitan Opera star Ezio Pinza for $25,000 to star in a new show, Mr. Ambassador. The show had not been written, and it never would be.[27] Lester hoped that Rodgers would take over Pinza's contract. Pinza had become bored as the Met's leading lyric bass, and having played the great opera houses, sought other worlds to conquer. Rodgers immediately saw Pinza as perfect for the role of Emile.[28] Lester carefully broached the subject to Pinza and his wife/business manager and provided them with a copy of Tales of the South Pacific. When Pinza read the book, he told Lester, "Sell me right away!"[29] Pinza's contract for South Pacific included a clause limiting his singing to 15 minutes per performance.[29] With Pinza's signing, Rodgers and Hammerstein decided to make his the lead male role, subordinating the story of the pair of young lovers. It was unusual on Broadway for the romantic lead to be an older male.[30]

For the role of Nellie, Rodgers sought Mary Martin, who had nearly been cast to originate the role of Laurey in Oklahoma! [30] Martin was playing the title role in the touring company of Annie Get Your Gun. After Hammerstein and Rodgers saw her play in Los Angeles in mid-1948, they asked her to consider the part. Martin was reluctant to sing opposite Pinza's powerful voice; Rodgers assured her he would see to it the two never sang at the same time,[31] a promise he mostly kept.[32] Rodgers and Martin lived near each other in Connecticut, and after her tour Rodgers invited Martin and her husband, Richard Halliday, to his home to hear the three songs for the musical that he had completed, none of them for Nellie.[33] "Some Enchanted Evening" especially struck Martin, and although disappointed the song was not for her, she agreed to do the part.[32] Although Nellie and Emile were already fully developed characters in Michener's stories, during the creation of South Pacific, Rodgers, Hammerstein and Logan began to adapt the roles specifically to the talents of Martin and Pinza and to tailor the music for their voices.[34]

Martin influenced several of her songs. While showering one day during rehearsals, she came up with the idea for a scene in which she would shampoo her hair onstage. This gave rise to "I'm Gonna Wash That Man Right Outa My Hair".[35] Built around a primitive shower that Logan remembered from his time in the military, the song became one of the most talked-about in South Pacific.[36] To introduce another of Martin's numbers to her, Rodgers called her over to his apartment, where he and Hammerstein played "I'm in Love with a Wonderful Guy" for her. When Martin essayed it for herself, she sang the final 26 words, as intended, with a single breath, and fell off her piano bench. Rodgers gazed down at her, "That's exactly what I want. Never do it differently. We must feel you couldn't squeeze out another sound."[37]

The producers held extensive auditions to fill the other roles.[38] Myron McCormick was cast as Billis; according to Logan, no one else was seriously considered. The two roles which gave the most trouble were those of Cable and Bloody Mary.[39] They tried to get Harold Keel for the role of Cable (he had played Curly in the West End production of Oklahoma!) only to find that he had signed a contract with MGM under the name Howard Keel.[40] William Tabbert was eventually cast as Cable, though Logan instructed him to lose 20 pounds (9.1 kg). African-American singer Juanita Hall was cast as Bloody Mary; Logan recalled that at her audition, she took a squatting pose which proclaimed, "I am Bloody Mary and don't you dare cast anyone else!"[39] Betta St. John, who under the name Betty Striegler had replaced Bambi Linn as Louise in Carousel, took the role of Liat.[40] Logan directed (he and Hayward co-produced with Rodgers and Hammerstein), Mielziner did the stage design, Trude Rittmann and Robert Russell Bennett prepared the orchestration, and Elizabeth Montgomery of Motley Theatre Design Group designed the costumes.[38] Salvatore Dell'Isola served as music director.[41]

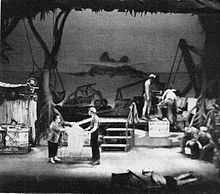

Original production

Rehearsals began at Broadway's Belasco Theatre on February 2, 1949. There was no formal chorus; each of the nurses and Seabees was given a name, and, in the case of the men, $50 to equip themselves with what clothing they felt their characters would wear from the military surplus shops which lined West 42nd Street. Don Fellows, the first Lt. Buzz Adams, drew on his wartime experience as a Marine to purchase a non-regulation baseball cap and black ankle boots.[42] Martin and Pinza had not known each other, but they soon formed a strong friendship.[43] Of the mood backstage, "everyone agreed: throughout the rehearsals Logan was fiery, demanding, and brilliantly inventive."[44] He implemented lap changes (pioneered by Rodgers and Hammerstein in Allegro), whereby the actors coming on next would already be on a darkened part of the stage as one scene concluded. This allowed the musical to continue without interruption by scene changes, making the action almost seamless. He soon had the Seabees pacing back and forth like caged animals during "There Is Nothing Like a Dame", a staging so effective it was never changed during the run of the show.[44] One Logan innovation that Rodgers and Hammerstein reluctantly accepted was to have Cable remove his shirt during the blackout after he and Liat passionately embrace on first meeting, his partial nakedness symbolizing their lovemaking.[45] As originally planned, Martin was supposed to conclude "I'm in Love with a Wonderful Guy" with an exuberant cartwheel across the stage. This was eliminated after she vaulted into the orchestra pit, knocking out Rittman.[46]

There were no major difficulties during the four weeks of rehearsal in New York; Martin later remembered that the "gypsy run-through" for friends and professional associates on a bare stage was met with some of the most enthusiastic applause she could remember. One of the few people having trouble was Pinza, who had difficulty adjusting to the constant alterations in the show – he was used to the operatic world, where a role rarely changed once learned. Pinza's mispronunciations of English exasperated Logan, and driving to New Haven for the first week of previews, Pinza discussed with his wife the possibility of a return to the Met, where he knew audiences would welcome him. She told him to let South Pacific 's attendees decide for themselves. When the tryouts began in New Haven on March 7, the play was an immediate hit; the New Haven Register wrote, "South Pacific should make history".[47]

Nevertheless, a number of changes were made in New Haven and in the subsequent two weeks of previews in Boston. The show was running long; Logan persuaded his friend, playwright Emlyn Williams, to go over the script and cut extraneous dialogue.[48] There were wide expectations of a hit; producer Mike Todd came backstage and advised that the show not be taken to New York "because it's too damned good for them".[49] The show moved to Boston, where it was so successful that playwright George S. Kaufman joked that people lining up there at the Shubert Theatre "don't actually want anything ... They just want to push money under the doors."[50]

South Pacific opened on Broadway on April 7, 1949, at the Majestic Theatre.[51] The advance sale was $400,000, and an additional $700,000 in sales was made soon after the opening. The first night audience was packed with important Broadway, business, and arts leaders. The audience repeatedly stopped the show with extended applause, which was sustained at length at the final curtain. Rodgers and Hammerstein had preferred, in the past, not to sponsor an afterparty, but they rented the St. Regis Hotel's roof and ordered 200 copies of The New York Times in the anticipation of a hit. Times critic Brooks Atkinson gave the show a rave review.[52]

Three days after the opening, Pinza signed a contract with MGM to star in films once his obligation to appear in the show expired. He left the show June 1, 1950, replaced by Ray Middleton, though Pinza missed a number of shows due to illness before that. Martin recalled that, unused to performing eight shows a week, the former opera star would sing full out early in the week, leaving himself little voice towards the end, and would have his understudy go on.[53][54] Nevertheless, during the year he was in the show, and although aged 58, he was acclaimed as a sex symbol; George Jean Nathan wrote that "Pinza has taken the place of Hot Springs, Saratoga, and hormone injections for all the other old boys".[54]

A national tour began in Cleveland, Ohio, in April 1950; it ran for five years and starred Richard Eastham as Emile, Janet Blair as Nellie and Ray Walston as Billis, a role Walston would reprise in London and in the 1958 film. For the 48,000 tickets available in Cleveland, 250,000 requests were submitted, causing the box office to close for three weeks to process them.[55] Jeanne Bal and Iva Withers were later Nellies on this tour.[56] A scaled-down version toured military bases in Korea in 1951; by the request of Hammerstein and Rodgers, officers and enlisted soldiers sat together to view it.[54]

Martin left the Broadway production in 1951 to appear in the original London West End production; Martha Wright replaced her. Despite the departure of both original stars, the show remained a huge attraction in New York.[57] Cloris Leachman also played Nellie during the New York run; George Britton was among the later Emiles.[58] The London production ran from November 1, 1951 for 802 performances at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Logan directed; Martin and Wilbur Evans starred, with Walston as Billis, Muriel Smith as Bloody Mary and Ivor Emmanuel in the small role of Sgt. Johnson.[59][60] Sean Connery and Martin's son Larry Hagman, both at the start of their careers, played Seabees in the London production;[61] Julie Wilson eventually replaced Martin.[62] On January 31, 1952, King George VI attended the production with his daughter Princess Elizabeth and other members of the Royal Family.[63] He died less than a week later.[64]

The Broadway production transferred to the Broadway Theatre in June 1953 to accommodate Rodgers and Hammerstein's new show, Me and Juliet, although South Pacific had to be moved to Boston for five weeks because of schedule conflicts.[65] When it closed on January 16, 1954, after 1,925 performances, it was the second-longest-running musical in Broadway history, after Oklahoma!. At the final performance, Myron McCormick, the only cast member remaining from the opening, led the performers and audience in "Auld Lang Syne"; the curtain did not fall but remained raised as the audience left the theatre.[66]

Synopsis

Act I

On a South Pacific island during World War II, two half-Polynesian children,[n 4] Ngana and Jerome, happily sing as they play together ("Dites-Moi"). Ensign Nellie Forbush, a naïve U.S. Navy nurse from Little Rock, Arkansas, has fallen in love with Emile de Becque, a middle-aged French plantation owner, though she has known him only briefly. Even though everyone else is worried about the outcome of the war, Nellie tells Emile that she is sure everything will turn out all right ("A Cockeyed Optimist"). Emile also loves Nellie, and each wonders if the other reciprocates those feelings ("Twin Soliloquies"). Emile expresses his love for Nellie, recalling how they met at the officers' club dance and instantly were attracted to each other ("Some Enchanted Evening"). Nellie, promising to think about their relationship, returns to the hospital. Emile calls Ngana and Jerome to him, revealing to the audience that they are his children, unbeknownst to Nellie.

Meanwhile, the restless American Seabees, led by crafty Luther Billis, lament the absence of available women – Navy nurses are commissioned officers and off-limits to enlisted men. There is one civilian woman on the island, nicknamed "Bloody Mary", a sassy middle-aged Tonkinese vendor of grass skirts, who engages the sailors in sarcastic, flirtatious banter as she tries to sell them her wares ("Bloody Mary"). Billis yearns to visit the nearby island of Bali Ha'i – which is off-limits to all but officers – supposedly to witness a Boar's Tooth Ceremony (at which he can get an unusual native artifact); the other sailors josh him, saying that his real motivation is to see the young French women there. Billis and the sailors further lament their lack of feminine companionship ("There Is Nothing Like a Dame").

U.S. Marine Lieutenant Cable arrives on the island from Guadalcanal, having been sent to take part in a dangerous spy mission whose success could turn the tide of the war against Japan. Bloody Mary tries to persuade Cable to visit "Bali Ha'i", mysteriously telling him that it is his special island. Billis, seeing an opportunity, urges Cable to go. Cable meets with his commanding officers, Captain George Brackett and Commander William Harbison, who plan to ask Emile to help with the mission because he used to live on the island where the mission will take place. They ask Nellie to help them find out more about Emile's background, for example, his politics and why he left France. They have heard, for instance, that Emile committed a murder, and this might make him less than desirable for such a mission.

After thinking a bit more about Emile and deciding she has become attracted on the basis of little knowledge of him, Nellie tells the other nurses that she intends to spurn him ("I'm Gonna Wash That Man Right Outa My Hair"). When he arrives unexpectedly and invites Nellie to a party where he will introduce her to his friends, however, she accepts. Emile declares his love for Nellie and asks her to marry him. When she mentions politics, he speaks of universal freedom, and describes fleeing France after standing up against a bully, who died accidentally as the two fought. After hearing this, Nellie agrees to marry Emile. After he exits, Nellie joyously gives voice to her feelings ("I'm in Love with a Wonderful Guy").

Cable's mission is to land on a Japanese-held island and report on Japanese ship movements. The Navy officers ask Emile to be Cable's guide, but he refuses their request because of his hopes for a new life with Nellie. Commander Harbison, the executive officer, tells Cable to go on leave until the mission can take place, and Billis obtains a boat and takes Cable to Bali Ha'i. There, Billis participates in the native ceremony, while Bloody Mary introduces Cable to her beautiful daughter, Liat, with whom he must communicate haltingly in French. Believing that Liat's only chance at a better life is to marry an American officer, Mary leaves Liat alone with Cable. The two are instantly attracted to each other and make love ("Younger Than Springtime"). Billis and the rest of the crew are ready to leave the island, yet must wait for Cable who, unbeknownst to them, is with Liat ("Bali Ha'i" (reprise)). Bloody Mary proudly tells Billis that Cable is going to be her son-in-law.

Meanwhile, after Emile's party, Nellie and he reflect on how happy they are to be in love (Reprises of "I'm in Love with a Wonderful Guy", "Twin Soliloquies", "Cockeyed Optimist" and "I'm Gonna Wash That Man Right Outa My Hair"). Emile introduces Nellie to Jerome and Ngana. Though she finds them charming, she is shocked when Emile reveals that they are his children by his first wife, a dark-skinned Polynesian woman, now deceased. Nellie is unable to overcome her deep-seated racial prejudices and tearfully leaves Emile, after which he reflects sadly on what might have been ("Some Enchanted Evening" (reprise)).

Act II

It is Thanksgiving Day. The GIs and nurses dance in a holiday revue titled "Thanksgiving Follies". In the past week, an epidemic of malaria has hit the island of Bali Ha'i. Having visited Bali Ha'i often to be with Liat, Cable is also ill, but escapes from the hospital to be with Liat. As Liat and Cable spend more time together, Bloody Mary is delighted. She encourages them to continue their carefree life on the island ("Happy Talk") and urges them to marry. Cable, aware of his family's prejudices, says he cannot marry a Tonkinese girl. Bloody Mary furiously drags her distraught daughter away, telling Cable that Liat must now marry a much older French plantation owner instead. Cable laments his loss. ("Younger Than Springtime" (reprise)).

For the final number of the Thanksgiving Follies, Nellie performs a comedy burlesque dressed as a sailor singing the praises of "his" sweetheart ("Honey Bun"). Billis plays Honey Bun, dressed in a blond wig, grass skirt and coconut-shell bra. After the show, Emile asks Nellie to reconsider. She insists that she cannot feel the same way about him since she knows about his children's Polynesian mother. Frustrated and uncomprehending, Emile asks Cable why he and Nellie have such prejudices. Cable, filled with self-loathing, replies that "it's not something you're born with", yet it is an ingrained part of their upbringing ("You've Got to Be Carefully Taught"). He also vows that if he gets out of the war alive, he won't go home to the United States; everything he wants is on these islands. Emile imagines what might have been ("This Nearly Was Mine"). Dejected and feeling that he has nothing to lose, he agrees to join Cable on his dangerous mission.

The mission begins with plenty of air support. Offstage, Billis stows away on the plane, falls out when the plane is hit by anti-aircraft fire, and ends up in the ocean waiting to be rescued; the massive rescue operation inadvertently becomes a diversion that allows Emile and Cable to land on the other side of the island undetected. The two send back reports on Japanese ships' movements in the "Slot", a strategic strait; American aircraft intercept and destroy the Japanese ships. When the Japanese Zeros strafe the Americans' position, Emile narrowly escapes, but Cable is killed.

Nellie learns of Cable's death and that Emile is missing. She realizes that she was foolish to reject Emile because of the race of his children's mother. Bloody Mary and Liat come to Nellie asking where Cable is; Mary explains that Liat refuses to marry anyone but him. Nellie comforts Liat. Cable and Emile's espionage work has made it possible for a major offensive, Operation Alligator, to begin. The previously idle fighting men, including Billis, go off to battle.

Nellie spends time with Jerome and Ngana and soon comes to love them. While the children are teaching her to sing "Dites-Moi," suddenly Emile's voice joins them. Emile has returned to discover that Nellie has overcome her prejudices and has fallen in love with his children. Emile, Nellie and the children rejoice ("Dites-Moi" (reprise)).

Principal roles and notable performers

Songs

|

|

Additional songs

A number of songs were extensively modified, or were omitted, in the weeks leading up to the initial Broadway opening. They are listed in the order of their one-time placement within the show:

- "Bright Canary Yellow", a short song for Nellie and Emile, was placed just before "A Cockeyed Optimist", of which the opening line, "When the sky is a bright canary yellow" was intended to play off of the earlier song.[68]

- "Now Is the Time" (Emile) was placed in the beach scene (Act I, Scene 7) just after Emile tells Nellie why he killed the man in France. It was to be reprised after "You've Got to Be Carefully Taught", but it was felt that for Emile to remain on stage while singing of immediate action was self-contradictory. It was replaced in Act I by a reprise of "Some Enchanted Evening"; in Act II it was initially replaced by "Will You Marry Me?" (later repurposed for Pipe Dream) on March 24, 1949, and then by "This Nearly Was Mine" on March 29, just over a week before the Broadway opening on April 7.[69]

- "Loneliness of Evening" (Emile) was cut before the Broadway opening. It was to occur in the first backstage scene (Act II, Scene 2) prior to "Happy Talk" and was sung to the same melody as "Bright Canary Yellow". Its melody can be heard in the 1958 film as Emile reads aloud the card with the flowers he has brought backstage for Nellie to the Thanksgiving show; the second stanza was repurposed and sung by the Prince in the 1965 TV production of Cinderella.[70]

- A reprise of "Younger Than Springtime" that follows Cable's rejection of Liat, was added after January 1949.[71] It followed two separate attempts at songs for Cable. One song, designated as "My Friend" was a duet for Cable and Liat, included such lyrics as "My friend, my friend, is coming around the bend" and was rejected by Logan as one of the worst he'd ever heard. Rodgers and Hammerstein's second attempt to place a song there, "Suddenly Lovely", was considered by Logan too lightweight and was later repurposed for The King and I as "Getting to Know You".[72] The melody for "Younger than Springtime" was from a song, "My Wife", intended for Allegro but not used.[73]

- "Honey Bun" was not included in the January 1949 libretto (a note marks that the lyrics will be supplied later).[71]

- "My Girl Back Home" (Cable) preceded "You've Got to be Carefully Taught" in the original score but was cut before the first Broadway production. It appears in the movie version as a duet for Nellie and Cable. It was reinstated for the 2002 London revival, for Cable.[74]

- "You've Got to be Carefully Taught" originally had several singing lines for Emile following the conclusion of the lyrics for Cable.[74]

Revivals

20th century

A limited run of South Pacific by the New York City Center Light Opera Company opened at New York City Center on May 4, 1955, closing on May 15, 1955. It was directed by Charles Atkin, and had costumes by Motley and sets by Mielziner. The cast included Richard Collett as Emile, Sandra Deel as Nellie, Carol Lawrence as Liat, Sylvia Syms as Bloody Mary and Gene Saks as the Professor.[75] A second limited run of the same production with a different cast opened at City Center on April 24, 1957, closing on May 12, 1957. It was directed by Jean Dalrymple, and the cast included Robert Wright as Emile, Mindy Carson as Nellie and Hall reprising the role of Bloody Mary.[76] That production was given again in 1961, this time with Ann McLerie and William Chapman in the lead roles.[77]

There have been many stock or summer revivals of South Pacific. One, in 1957 at Long Island's Westbury Music Fair, occurred at the same time that Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus was resisting the integration of Central High School by the Little Rock Nine. Nellie's pronouncement that she was from Little Rock was initially met with boos. Logan refused to allow Nellie's hometown to be changed, so a speech was made before each performance asking for the audience's forbearance, which was forthcoming.[78]

There were two revivals at Lincoln Center. Richard Rodgers produced the 1967 revival, which starred Florence Henderson and Giorgio Tozzi, who had been Rossano Brazzi's singing voice in the 1958 film.[79] Joe Layton was the director.[77] The cast album was issued on LP and later on CD.[79][80] The musical toured North America from 1986 to 1988, headlined by Robert Goulet and Barbara Eden, with David Carroll as Cable, Armelia McQueen as Bloody Mary and Lia Chang as Liat, first directed by Geraldine Fitzgerald and then Ron Field.[81] A New York City Opera production in 1987 featured alternating performers Justino Díaz and Stanley Wexler as Emile, and Susan Bigelow and Marcia Mitzman as Nellie.[82]

A 1988 West End revival starred Gemma Craven and Emile Belcourt, supported by Bertice Reading, among others, and was directed by Roger Redfern. It ran at the Prince of Wales Theatre from January 20, 1988 to January 14, 1989.[83]

21st century

A new production with slight revisions to the book and score was produced by the Royal National Theatre at the company's Olivier Theatre in London for a limited run from December 2001 through April 2002, timed to celebrate the centenary of Richard Rodgers' birth. Trevor Nunn directed, with musical staging by Matthew Bourne and designs by John Napier. Lauren Kennedy was Nellie, and Australian actor Philip Quast played Emile,[84] Borrowing from the 1958 film, this production placed the first Emile-Nellie scene after the introduction of Cable, Billis and Bloody Mary.[85]

A British touring production of South Pacific opened at the Blackpool Grand Theatre on August 28, 2007. The tour ended at the Cardiff New Theatre on July 19, 2008.[86] It starred Helena Blackman as Nellie and Dave Willetts as Emile. Julian Woolford directed, with choreography by Chris Hocking. This production was most noted for its staging of the overture, which charted Nellie's journey from Little Rock, Arkansas, to the South Pacific. On entering the theatre, the audience first saw a map of the U.S., not the theater of war.[87]

A Broadway revival of South Pacific opened on April 3, 2008 at Lincoln Center's Vivian Beaumont Theater. Bartlett Sher directed, with musical staging by Christopher Gattelli and associate choreographer Joe Langworth. The opening cast starred Kelli O'Hara as Nellie, Paulo Szot as Emile and Matthew Morrison as Lt. Cable, with Danny Burstein as Billis and Loretta Ables Sayre as Bloody Mary.[88] Laura Osnes replaced O'Hara during her seven-month maternity leave, beginning in March 2009,[89] and also between January and August 2010.[90][91] Szot alternated with David Pittsinger as Emile.[92] The production closed on August 22, 2010, after 37 previews and 996 regular performances.[93]

With a few exceptions, the production received rave reviews.[94] Ben Brantley wrote in The New York Times:

I know we're not supposed to expect perfection in this imperfect world, but I'm darned if I can find one serious flaw in this production. (Yes, the second act remains weaker than the first, but Mr. Sher almost makes you forget that.) All of the supporting performances, including those of the ensemble, feel precisely individualized, right down to how they wear Catherine Zuber's carefully researched period costumes.[95]

The production, with most of the original principals, was taped and broadcast live in HD on August 18, 2010 on the PBS television show Live from Lincoln Center.[96]

A production based on the 2008 Broadway revival opened at the Barbican Theatre in London on August 15, 2011 and closed on October 1, 2011.[97] Sher again directed, with the same creative team from the Broadway revival. Szot and Welsh National Opera singer Jason Howard alternated in the role of Emile, with Samantha Womack as Nellie, Ables Sayre as Bloody Mary and Alex Ferns as Billis. The production received mostly positive reviews.[98] A U.K tour followed, with Womack, Ables Sayre and Ferns.[99]

A U.S. national tour based on the 2008 revival began in San Francisco at the Golden Gate Theatre on September 18, 2009. Sher directed, and the cast starred Rod Gilfry (Emile) and Carmen Cusack (Nellie).[100] The Sher production was also produced by Opera Australia at the Sydney Opera House from August to September 2012 and then at Princess Theatre, Melbourne through October 2012. It starred Teddy Tahu Rhodes as Emile, Lisa McCune as Nellie, Kate Ceberano as Bloody Mary and Eddie Perfect as Billis.[101] The production then played in Brisbane for the 2012 holiday season, with Christine Anu as Bloody Mary,[102] and resumed touring in Australia in September 2013.[103][104]

Reception and success

Critical reception

Reviewers gave the original production uniformly glowing reviews; one critic called it "South Terrific".[105] The New York Herald Tribune wrote:

The new and much-heralded musical, South Pacific, is a show of rare enchantment. It is novel in texture and treatment, rich in dramatic substance, and eloquent in song, a musical play to be cherished. Under Logan's superb direction, the action shifts with constant fluency. ... [He] has kept the book cumulatively arresting and tremendously satisfying. The occasional dances appear to be magical improvisations. It is a long and prodigal entertainment, but it seems all too short. The Rodgers music is not his finest, but it fits the mood and pace of South Pacific so felicitously that one does not miss a series of hit tunes. In the same way the lyrics are part and parcel of a captivating musical unity.[106]

The New York Daily Mirror critic wrote, "Programmed as a musical play, South Pacific is just that. It boasts no ballets and no hot hoofing. It has no chorus in the conventional sense. Every one in it plays a part. It is likely to establish a new trend in musicals." The review continued: "Every number is so outstanding that it is difficult to decide which will be the most popular."[106] The review in New York World-Telegram found the show to be "the ultimate modern blending of music and popular theatre to date, with the finest kind of balance between story and song, and hilarity and heartbreak."[106] Brooks Atkinson of The New York Times especially praised Pinza's performance: "Mr. Pinza's bass voice is the most beautiful that has been heard on a Broadway stage for an eon or two. He sings ... with infinite delicacy of feeling and loveliness of tone." He declared that "Some Enchanted Evening", sung by Pinza, "ought to become reasonably immortal."[106] Richard Watts, Jr. of the New York Post focused on Mary Martin's performance, writing, "nothing I have ever seen her do prepared me for the loveliness, humor, gift for joyous characterization, and sheer lovableness of her portrayal of Nellie Forbush ... who is so shocked to find her early racial prejudices cropping up. Hers is a completely irresistible performance."[106]

When South Pacific opened in London in November 1951, the reviews were mixed. London's Daily Express praised the music but disliked other elements of that show, writing, "We got a 42nd Street Madame Butterfly, the weakest of all the Hammerstein-Rodgers musicals.[61][107] The Daily Mail suggested, "The play moved so slowly between its songs that it seemed more like South Soporific."[61] The Times applauded the songs but indicated that "before the end the singing and the dancing have dwindled to almost nothing, while the rather sad little tale is slowly and conventionally wound up."[108] The Manchester Guardian, however, noted the anticipation in advance of the opening and concluded that "there was no disappointment ... the show bounces the audience and well deserves the cheers."[109] Drama critic Kenneth Tynan of The Spectator wrote that South Pacific was "the first musical romance which was seriously involved in an adult subject ... I have nothing to do but thank Logan, Rodgers and Hammerstein and climb up from my knees, a little cramped from the effort of typing in such an unusual position."[61]

A 2006 review asserted: "Many are the knowledgeable and discriminating people for whom Rodgers and Hammerstein's South Pacific, brilliantly co-written and staged by Joshua Logan, was the greatest musical of all."[110] In 1987, however, John Rockwell of The New York Times reviewed the City Opera production, commenting that while South Pacific had been innovative for 1949, "Sondheim has long since transcended its formal innovations, and the constant reprises of the big tunes sound mechanical. In 1949, South Pacific epitomized the concerns of the day – America's responsibilities in the world and the dangers of racism. ... At its 1967 State Theater revival, the show struck many as dated. It still seems that way, with M*A*S*H having contemporized this same setting".[111] A 2008 Huffington Post review criticized the play as having an Orientalist and Western-centric storyline in which stereotypical natives take on "exotic background roles" in relation to Americans, and it characterized the relationship between Cable and Liat as underage prostitution, charging that she "speaks not a word in the whole musical, only smiles and takes the Yankee to bed."[112] South Pacific is the only major American musical set in World War II,[113] but former Marine Robert Leckie wrote his memoir of that conflict, Helmet for My Pillow, after he walked out of a performance: "I have to tell the story of how it really was. I have to let people know the war wasn't a musical."[114]

Box office and awards

South Pacific opened on Broadway with $400,000 in advance sales. People were so eager to obtain tickets that the press wrote about the lengths people had gone to in getting them. Because "house seats" were being sold by scalpers for $200 or more, the attorney general's office threatened to close the show. However, the parties who provided the scalpers with the tickets were never identified, and the show ran without interference. The production had a $50,600 weekly gross, and ran for 1,925 performances. The national tour began in 1950 and grossed $3,000,000 in the first year, making $1,500,000 in profit. The original cast album, priced at $4.85, sold more than a million copies.[115]

The original production of South Pacific won ten Tony Awards, including Best Musical, Best Male Performer (Pinza), Best Female Performer (Martin), Best Supporting Male Performer (McCormick), Best Supporting Female Performer (Hall), Best Director (Logan), Best Book and Best Score.[116] In 1950, the musical won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, the second musical to do so after Of Thee I Sing, which won in 1932. Rodgers became the first composer of musical comedy to win the Pulitzer, as composer George Gershwin had not been recognized for Of Thee I Sing.[117] The Pulitzer Prize was initially given only to Rodgers and Hammerstein; Logan was later recognized in an amended announcement, much to his annoyance.[50]

The 2001 London revival garnered a Laurence Olivier Award for Philip Quast (Emile).[118] The 2008 revival won seven Tony Awards, including Best Revival (Sher and Szot also won, and the show won in all four design categories), and five Drama Desk Awards, including Outstanding Musical Revival. The late Robert Russell Bennett was also honored that season for "his historic contribution to American musical theatre in the field of orchestrations, as represented on Broadway this season by Rodgers and Hammerstein's South Pacific."[119][120] The 2011 London production received three Olivier Award nominations, including Best Musical Revival, but won none.[121][122]

Themes and cultural effect

Race

Part of the reason why South Pacific is considered a classic is its confrontation of racism. According to professor Philip Beidler, "Rodgers and Hammerstein's attempt to use the Broadway theater to make a courageous statement against racial bigotry in general and institutional racism in the postwar United States in particular" forms part of South Pacific 's legend.[123] Although Tales of the South Pacific treats the question of racism, it does not give it the central place that it takes in the musical. Andrea Most, writing on the "politics of race" in South Pacific, suggests that in the late 1940s, American liberals, such as Rodgers and Hammerstein, turned to the fight for racial equality as a practical means of advancing their progressive views without risking being deemed communists.[124] Trevor Nunn, director of the 2001 West End production, notes the importance of the fact that Nellie, a southerner, ends the play about to be the mother in an interracial family: "It's being performed in America in 1949. That's the resonance."[125]

From the early drafts, Hammerstein and Logan made the issue of racial prejudice central to the story. Hammerstein repeatedly rewrote the Act II backstage scene where Emile, Nellie and Cable confront the question of the Americans' racism.[126] As critic Robert Butler pointed out in his educational companion to the 2001 London production, "if one young person has a prejudice, it might be a character flaw; if two young people share a prejudice, it tells us something about the society in which they grew up".[113] In one draft, Emile advises that the Americans are no better than the Axis Powers, in their prejudice, and suggests they go home to sing songs about how all are created free and equal. Lovensheimer states that a postwar American audience would have found such onstage sentiments to be offensive. In the staged version, Emile's expressions are limited to two lines arguing that prejudice is not inborn.[126]

At the heart of this scene is Cable's song "You've Got to Be Carefully Taught", in which Cable realizes the sources of his own racism. Its frank lyrics made it perhaps the most controversial element of the show.[127] Michener recalled in his memoirs that a delegation of New Englanders had approached him after a New Haven tryout and urged him to recommend the song's removal to Rodgers and Hammerstein. When Michener told Hammerstein, he laughed and replied, "That's what the show is about!"[128] Boston drama critic Elliot Norton, after seeing the show in tryouts, strongly recommended its removal, or at least that Cable sing it less "briskly", as there was much bigotry in Boston; Logan replied that that was all the more reason for leaving it unaltered.[129] Several New York reviewers expressed discomfort with the song; Wolcott Gibbs wrote of "something called 'You've Got to Be Taught', a poem in praise of tolerance that somehow I found a little embarrassing" while John Mason Brown opined that he was "somewhat distressed by the dragged-in didacticism of such a plea for tolerance as 'You've Got to Be Taught'".[130] After the Broadway opening, Hammerstein received a large number of letters concerning "You've Got to Be Carefully Taught". Judging by the letters that remain among his papers in the Library of Congress, the reaction was mixed. One correspondent wrote "What can I say to a man who writes, 'You've got to be taught to hate and fear?' ... Now that I know you, I feel that my informants didn't praise you enough."[131] Nevertheless, another wrote, "I feel the inclusion of the song particularly in the album and to some extent in the show itself is not helpful to the cause of brotherhood, your intent to the contrary notwithstanding".[131]

When the tour of the show reached a racially segregated theatre in Wilmington, Delaware, Rodgers and Hammerstein threatened to cancel the performances there unless seating was integrated, which it was.[132] In 1953, with the tour in Atlanta, there was controversy over "You've Got to Be Carefully Taught". Two Georgia state legislators, Senator John D. Shepard and Representative David C. Jones, objected to the song, stating that though South Pacific was a fine piece of entertainment, that song "contained an underlying philosophy inspired by Moscow", and explained, "Intermarriage produces half-breeds. And half-breeds are not conducive to the higher type of society. ... In the South, we have pure blood lines and we intend to keep it that way." They stated that they planned to introduce legislation to outlaw such communist-inspired works. The Northern press had a field day; Hammerstein, when asked for comment, responded that he did not think the legislators were representing their constituents very well, and that he was surprised at the suggestion that anything kind and decent must necessarily originate in Moscow.[132][133] In part because of the song, touring companies of South Pacific had difficulty getting bookings in the Deep South.[134]

In the final scene of Act I, Nellie rejects Emile because of his part-Polynesian children. In so doing, Nellie fails to live up to the American ideal that "all men are created equal", which Emile had earlier affirmed.[125] This scene was also toned down by Hammerstein; in early drafts, Nellie, initially unable to force out a word to describe Emile's first wife, after he supplies the word "Polynesian", responds with "colored". This pronouncement, which makes Nellie less sympathetic as a character, was restored for the 2008 Lincoln Center production. As Frank Rich of The New York Times commented, "it's upsetting because Nellie isn't some cracker stereotype – she's lovable ... But how can we love a racist?"[135] Most argues that even Emile is tainted by racism, as his lifestyle is dependent on the maintenance of a system whereby he benefits from underpaid native labor – Bloody Mary is able to attract workers to make grass skirts for sale to GIs because, as she puts it, "French planters stingy bastards!"[136]

Sex and gender roles

Nellie Forbush, in her journey from Little Rock, Arkansas, to serving as a Navy nurse and on to the domesticity of the final scene of South Pacific, parallels the experience of many American women of the period. They entered the workforce during the war, only to find afterwards a societal expectation that they give up their jobs in favor of men, with their best route to financial security being marriage and becoming a housewife. One means of securing audience acceptance of Nellie's choices was the sanitization of her sexual past from her counterpart in the Michener work – that character had a 4-F boyfriend back in Arkansas and a liaison with Bill Harbison while on the island.[137][138]

The male characters in South Pacific are intended to appear conventionally masculine. In the aftermath of World War II, the masculinity of the American soldier was beyond public question. Cable's virility with Liat is made evident to the audience. Although Billis operates a laundry – Nellie particularly praises his pleats – and appears in a grass skirt in the "Thanksgiving Follies", these acts are consistent with his desire for money and are clearly intended to be comic. His interest in the young ladies on Bali H'ai establishes his masculinity. Lovensheimer writes that Billis is more defined by class than by sexuality, evidenced by the Seabee's assumption, on learning that Cable went to college in New Jersey, that it was Rutgers (the state's flagship public university), rather than Ivy League Princeton, and by his delight on learning that the rescue operation for him had cost $600,000 when his uncle had stated he would never be worth a dime.[139][140]

Meryle Secrest, in her biography of Rodgers, theorizes that South Pacific marks a transition for the pair "between heroes and heroines who are more or less evenly matched in age and stories about powerful older men and the younger women who are attracted to them".[141] Lovensheimer, however, points out that this pattern really only holds for two of their five subsequent musicals, The King and I and The Sound of Music, and in the former, the love between Anna and the King is not expressed in words. He believes a different transition took place: that their plots, beginning with South Pacific, involve a woman needing to enter and accept her love interest's world to be successful and accepted herself. He notes that both Oklahoma! and Carousel involve a man entering his wife's world, Curly in Oklahoma! about to become a farmer with expectations of success, whereas Billy Bigelow in Carousel fails to find work after leaving his place as a barker. Lovensheimer deems Allegro to be a transition, where the attempts of the lead female character to alter her husband Joe's world to suit her ambition lead to the breakup of their marriage. He argues that the nurse Emily, who goes with Joe in his return to the small town where he was happy, is a forerunner of Nellie, uprooting her life in Chicago for Joe.[142]

Secrest notes that much is overlooked in the rush to have love conquer all in South Pacific, "questions of the long-term survival of a marriage between a sophisticate who read Proust at bedtime and a girl who liked Dinah Shore and did not read anything were raised by Nellie Forbush only to be brushed aside. As for the interracial complexities of raising two Polynesian children, all such issues were subsumed in the general euphoria of true love."[143] Lovensheimer too wonders how Nellie will fare as the second Madame de Becque, "little Nellie Forbush from Arkansas ends up in a tropical paradise, far from her previous world, with a husband, a servant, and two children who speak a language she does not understand".[144]

Cultural effect

A mammoth hit, South Pacific sparked huge media and public attention. South Pacific was one of the first shows for which a variety of souvenirs were available: fans could buy South Pacific neckties, or for women, lipstick and scarves. Fake ticket stubs could be purchased for use as status symbols.[117] There were South Pacific music boxes, dolls, fashion accessories and even hairbrushes for use after washing men from hair.[145] Martin's on-stage shower prompted an immediate fashion craze for short hair that could be managed through once-a-day washing at home, rather than in a beauty salon, and for the products which would allow for such care.[146] The songs of South Pacific could be heard on the radio, and they were popular among dance bands and in piano lounges.[117] Mordden comments that South Pacific contained nothing but hit songs; Rodgers and Hammerstein's other successful works always included at least one song which did not become popular.[147]

The cast album, recorded ten days after the show's opening, was an immediate hit. Released by Columbia Records, it spent 69 weeks at #1 on Billboard and a total of 400 weeks on the charts, becoming the best-selling record of the 1940s.[117] It was one of the early LP records, with a turntable speed of 33⅓ rpm, and helped to popularize that technology – previously, show albums and operas had been issued on sets of 78 rpm records, with high prices and much less music on a single disc. In the years to come, the LP would become the medium of choice for the "longhair" music niche of show, opera and classical performances.[148]

An indirect effect of the success of the show was the career of James Michener. His one percent of the show as author of the source material, plus the income from a share which the duo allowed him to buy on credit, made him financially independent and allowed him to quit his job as an editor at Macmillan and to become a full-time writer.[149][150] Over the next five decades, his lengthy, detailed novels centering on different places would dominate the bestseller lists.[151]

Music and recordings

Musical treatment

The role of Nellie Forbush was the first time with Hammerstein that Rodgers made the leading female role a belter, rather than a lyric soprano like Laurey in Oklahoma! and Julie in Carousel.[n 5] According to Mordden, "Nellie was something new in R&H, carrying a goodly share of the score on a 'Broadway' voice".[152]

Nellie does not sing together with Emile, because Rodgers promised Martin that she would not have to compete vocally with Pinza,[n 6] but the composer sought to unite them in the underlying music. A tetrachord, heard before we see either lead, is played during the instrumental introduction to "Dites-Moi ", the show's first song. Considered as pitch classes, that is, as pitches without characterization by octave or register, the motif is C-B-A-G. It will be heard repeatedly in Nellie's music, or in the music (such as "Twin Soliloquies") that she shares with Emile, and even in the bridge of "Some Enchanted Evening". Lovensheimer argues that this symbolizes what Nellie is trying to say with her Act II line "We're the same sort of people fundamentally – you and me".[153]

Originally, "Twin Soliloquies" came to an end shortly after the vocal part finishes. Logan found this unsatisfying and worked with Trude Rittmann to find a better ending to the song. This piece of music, dubbed "Unspoken Thoughts", continues the music as Nellie and Emile sip brandy together, and is called by Lovensheimer "the one truly operatic moment of the score".[154] "This Nearly Was Mine" is a big bass solo for Emile in waltz time, deemed by Rodgers biographer William G. Hyland as "one of his finest efforts".[155] Only five notes are used in the first four bars, a phrase which is then repeated with a slight variation in the following four bars. The song ends an octave higher than where it began, making it perfect for Pinza's voice.[155]

Two songs, "I'm Gonna Wash That Man Right Outa My Hair" and "Honey Bun" are intended to imitate American popular songs of the 1940s. In the former, the triple recitation of the song title at intervals suggests a big band arrangement of the wartime era, while in the bridge, the final eight bars (repeating the lyrics from the bridge's first eight bars) gives a suggestion of swing. The sections beginning "If the man don't understand you" and "If you laugh at different comics" have a blues style. Lovensheimer deems the song "Nellie's spontaneous and improvisatory expression of her feelings through the vocabulary of popular song".[156] Mordden suggests that "I'm in Love with a Wonderful Guy" with its "take no prisoners bounce", might well be the center of the score, with the typical American girl defending her love by spouting clichés, many of which, such as "corny as Kansas in August" Hammerstein made up, and "sure enough, over the years they have become clichés".[157]

Recordings

Columbia Records recorded the overture and most of the songs from the original production in 1949, using members of the cast including Ezio Pinza and Mary Martin. Drawing from the original masters, Columbia released the album in both the new LP format and on 78-rpm discs. Soon after Sony acquired Columbia in 1988, a CD was released from the previously unused magnetic tape recording from the same 1949 sessions in New York City. The CD includes the bonus tracks "Loneliness of Evening" (recorded in 1949 by Mary Martin), "My Girl Back Home" (Martin), "Bali Ha'i" (Pinza) and Symphonic Scenario for Concert Orchestra (original orchestrations by Robert Russell Bennett). According to critic John Kenrick, the original cast recording "is the rare stuff that lasting legends are made of", an essential classic.[158] The original cast album was added to the National Recording Registry in the Library of Congress on March 21, 2013 for long-term preservation.[159] The film soundtrack was released on the RCA Victor label in March 1958.[160] Kenrick calls the recording "mixed up" and does not recommend it.[158]

Masterworks Broadway released a recording of the 1967 Lincoln Center production starring Florence Henderson as Nellie, Giorgio Tozzi as Emile, Justin McDonough as Cable and Irene Byatt as Bloody Mary. The recording includes a version of "Bali Ha'i", sung in French by Eleanor Calbes, the Liat. According to Kenrick, "Every track of this 1967 Lincoln Center cast recording is such a winner that you can't help wondering why it took so long for this winner to make its way to CD."[161] Kenrick notes that the album is a more complete alternative to the original cast album.[79][158]

In 1986 José Carreras and Kiri Te Kanawa made a studio recording of South Pacific, the sessions of which were filmed as a documentary, similar in style to Leonard Bernstein's successful West Side Story documentary a year earlier that featured the same stars. Emile's music was transposed to fit Carreras's tenor voice. The recording also featured Sarah Vaughan as Bloody Mary and Mandy Patinkin as Cable. Stephen Holden reviewed the album in The New York Times, "the star of this South Pacific isn't any individual, but rather the score itself".[162] Kenrick calls the recording badly miscast "pretentious trash."[158] Kenrick gives mixed praise to the 1988 London revival cast album.[158]

The 2001 Royal National Theatre's revival cast album was recorded in 2002 on First Night Records with Philip Quast as Emile, Lauren Kennedy as Nellie, Edward Baker-Duly as Cable, Sheila Francisco as Bloody Mary and Nick Holder as Billis. The album includes the cut song, "Now Is the Time". While Kenrick allows that most critics like the recording, he finds it a waste of money.[158] The 2005 Carnegie Hall concert version was released on April 18, 2006 by Decca Broadway with Reba McEntire as Nellie, Brian Stokes Mitchell as Emile, Lillias White as Bloody Mary, Jason Danieley as Cable and Alec Baldwin as Billis. Kendrick describes this recording as "one of the most ravishing that this glorious Rodgers & Hammerstein classic has ever received"[161] and "a show tune lover's dream come true."[158] The 2008 Broadway revival cast album was released on May 27, 2008 by Masterworks Broadway.[163] Kenrick finds it "very satisfying".[158]

Film and television versions

South Pacific was made into a film of the same name in 1958, and it topped the box office that year. Joshua Logan directed the film, which starred Rossano Brazzi, Mitzi Gaynor, John Kerr, Ray Walston and Juanita Hall; all of their singing voices except Gaynor's and Walston's were dubbed. Thurl Ravenscroft, later television's Tony the Tiger, sang the basso profundo notes in "There Is Nothing Like a Dame". The film opened with Cable's flight to the island in a PBY, followed by the Seabees' beach scene, and added Billis' rescue and scenes from the mission to spy on the Japanese. The film won the Academy Award for Best Sound. It was also nominated for the Oscar for Best Scoring of a Musical Picture (Alfred Newman and Ken Darby), and the 65 mm Todd-AO cinematography by Leon Shamroy was also nominated. The film was widely criticized for its use of color to indicate mood, with actors changing color as they began to sing. The film includes the song "My Girl Back Home", sung by Cable, which was cut from the stage musical. The movie was the third-highest-grossing film in the U.S. of the 1950s; its UK revenues were the highest ever, a record it kept until Goldfinger in 1963.[164][165] Although reviewers have criticized the film – Time magazine stated that it was "almost impossible to make a bad movie out of it – but the moviemakers appear to have tried" – it has added success on television, videotape and DVD to its box office laurels.[164]

A made-for-television film, directed by Richard Pearce, was produced and televised in 2001, starring Glenn Close as Nellie, Harry Connick, Jr. as Cable and Rade Sherbedgia as Emile. This version changed the order of the musical's songs (the film opens with "There Is Nothing Like a Dame") and omits "Happy Talk". "My Girl Back Home" was filmed but not included in the broadcast due to time constraints; it was restored for the DVD, issued in 2001. The last half-hour of the film features scenes of war, including shots of segregated troops.[166] Lovensheimer states that the film returned to the Michener original in one particular: "Harry Connick Jr.'s Joe Cable is a fascinating combination of sensitive leading man and believable Leatherneck".[167]

The movie and Close were praised by The New York Times: "Ms. Close, lean and more mature, hints that a touch of desperation lies in Nellie's cockeyed optimism." The review also commented that the movie "is beautifully produced, better than the stagy 1958 film" and praised the singing.[168] Kenrick, however, dislikes the adaptation: "You certainly won't ever want to put this disaster in your player, unless you want to hear the sound of Rodgers and Hammerstein whirling in their graves. Glenn Close is up to the material, but her supporting cast is uniformly disastrous. A pointless and offensive waste of money, time and talent."[169]

A 2005 concert version of the musical, edited down to two hours, but including all of the songs and the full musical score, was presented at Carnegie Hall. It starred Reba McEntire as Nellie, Brian Stokes Mitchell as Emile, Alec Baldwin as Billis and Lillias White as Bloody Mary. The production used Robert Russell Bennett's original orchestrations and the Orchestra of St. Luke's directed by Paul Gemignani. It was taped and telecast by PBS in 2006 and released the same year on DVD. The New York Times critic Ben Brantley wrote, "Open-voiced and open-faced, Reba McEntire was born to play Nellie"; the production was received "in a state of nearly unconditional rapture. It was one of those nights when cynicism didn't stand a chance."[170] Kenrick especially likes Mitchell's "This Nearly Was Mine", and praises the concert generally: "this excellent performance helped restore the reputation of this classic".[169]

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Michener later reflected, "I would often think of her ... when American troops were fighting their fruitless battles in Vietnam, and I wondered if our leaders realized that the enemy they were fighting consisted of millions of determined people like Bloody Mary." See May, p. 20

- ↑ The "De" was changed to lower case for the musical. See Maslon, p. 115.

- ↑ Jim Lovensheimer, in his book on the genesis of South Pacific, questions Logan's account: "in his autobiography, at least, Logan is the star of every show he mentions".[1]

- ↑ Although Hammerstein's script for the play calls them half-Polynesian, some productions, including the 2008 Broadway production, cast the children as half-black. This is consistent with Michener's novel, which takes place in the New Hebrides (Vanuatu). As part of Melanesia, its native inhabitants are black-skinned, and Michener repeatedly refers to the island natives as "black".

- ↑ The female lead in Allegro, Jenny, is principally a dancing role; the performer playing her does not sing by herself.

- ↑ They do sing together at the start of the final scene of Act I, but their characters are supposed to have been drinking.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lovensheimer, p. 46

- ↑ Lovensheimer, pp. 35–39

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lovensheimer, p. 39

- ↑ Lovensheimer, pp. 39, 191

- ↑ Lovensheimer, pp. 39–40

- ↑ Michener 1967, pp. 126–127

- ↑ Lovensheimer, pp. 43–44, 191

- ↑ Lovensheimer, pp. 49–50; and May, pp. 24–25

- ↑ Lovensheimer, pp. 52–53

- ↑ Hyland, p. 167

- ↑ Hischak, p. 202

- ↑ "The best of the century", Time, December 31, 1999, accessed December 21, 2010

- ↑ Hischak, pp. 5–7

- ↑ Nolan, p. 173

- ↑ Fordin, pp. 259–260; and Logan, pp. 266–267

- ↑ Lovensheimer, p. 47

- ↑ May, p. 80

- ↑ Fordin, pp. 261–262

- ↑ Maslon, p. 117

- ↑ Lovensheimer, pp. 58–67

- ↑ Rodgers and Hammerstein, pp. 310–313

- ↑ Logan, pp. 273–281; and May, pp. 98–103

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Hyland, p. 179

- ↑ Secrest, p. 290

- ↑ May, p. 100

- ↑ Nolan, pp. 184–186

- ↑ Maslon, p. 111

- ↑ Nolan, p. 178

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Maslon, p. 112

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Fordin, p. 262

- ↑ Davis, p. 123

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Hyland, p. 180

- ↑ Davis, p. 125

- ↑ "South Pacific: History, Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization, accessed August 29, 2012

- ↑ Hammerstein, p. 199

- ↑ Maslon, p. 93

- ↑ Nolan, p. 185

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Fordin, p. 267

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Logan, p. 283

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Nolan, p. 182

- ↑ Maslon, p. 124

- ↑ Maslon, pp. 124–125

- ↑ Davis, p. 130

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Nolan, p. 186

- ↑ Maslon, p. 121

- ↑ Logan, p. 289

- ↑ Maslon, pp. 126, 129

- ↑ Maslon, p. 129

- ↑ Nolan, p. 191

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Nolan, pp. 190–195

- ↑ Hischak, p. 261

- ↑ Fordin, p. 281

- ↑ Davis, p. 145

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Maslon, p. 154

- ↑ Maslon, pp. 153–154

- ↑ Green, p. 399

- ↑ Davis, p. 147

- ↑ Mordden 1999, p. 265

- ↑ Green, p. 398

- ↑ Hischak, p. 263

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 Maslon, p. 156

- ↑ Gould, Mark R. "Revival of South Pacific", American Library Association, 2012, accessed May 23, 2013

- ↑ "King enjoys South Pacific", The Age, February 1, 1952, p. 1, accessed June 5, 2013

- ↑ Fox, Jack V. "King George VI dies", UPI via Pittsburgh Press, February 6, 1952, p. 1, accessed June 5, 2013

- ↑ Nolan, p. 119

- ↑ Fordin, p. 282

- ↑ Rodgers & Hammerstein, p. 269 (roles and original cast only)

- ↑ Block, pp. 139–140

- ↑ Block, pp. 140–145

- ↑ Block, pp. 139, 142–143

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Block, p. 142

- ↑ Block, pp. 142, 145–146

- ↑ Nolan, p. 190

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Block, pp. 142, 146

- ↑ Funke, Lewis. "Theatre: Back to Bali Ha'i", The New York Times, May 5, 1955, p. 39

- ↑ "South Pacific (1957 City Center Revival)", NYPL Digital Gallery, accessed December 7, 2011

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Hischak, p. 264

- ↑ Maslon, p. 158

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 "Review, South Pacific (Music Theater of Lincoln Center Recording)", Allmusic.com, accessed April 20, 2011

- ↑ Suskin, Steven. "On The Record: 1960's revivals of South Pacific and The King and I", Playbill.com, September 17, 2006

- ↑ Nelson, Nels. "South Pacific at Valley Forge Music Fair", Philadelphia Daily News, Philly.com, July 9, 1986, accessed September 25, 2013; "Lia Chang", Bio & Reel, Lifeyo.com, accessed September 25, 2013; Smith, Sid. "Some Enchanted Musical with Robert Goulet in the Role of Emile De Becque, A Revived South Pacific Is Again a Hit.", Chicago Tribune, November 13, 1988, accessed September 25, 2013

- ↑ Hischak, Thomas S. "'South Pacific'", The Oxford Companion to the American Musical: Theatre, Film, and Television, Oxford University Press US, 2008, ISBN 0-19-533533-3, p. 700

- ↑ "Prince of Wales Theatre", Broadwayworld.com, accessed August 29, 2012

- ↑ "Musical Notes", Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization, January 1, 2002, accessed May 27, 2013

- ↑ Maslon, p. 182

- ↑ "'South Pacific' UK Tour", thisistheatre.com, accessed April 23, 2011

- ↑ Somensky, Amy. "U.K. tour of South Pacific opens today", Monstersandcritics.com, August 24, 2007, accessed May 25, 2013

- ↑ Hetrick, Adam. "Sher to Discuss South Pacific at Vivian Beaumont March 26", Playbill.com, March 7, 2008

- ↑ Hetrick, Adam. "Kelli O'Hara Rejoins South Pacific Cast Oct. 13", Playbill.com, October 13, 2009

- ↑ Hetrick, Adam. "Osnes Will Return to Broadway's South Pacific; O'Hara to Depart Jan. 3, 2010", Playbill.com, December 17, 2009

- ↑ Hetrick, Adam. "Kelli O'Hara Returns to South Pacific for Musical's Final Weeks Aug. 10", Playbill.com, August 10, 2010

- ↑ "South Pacific to End Record-Breaking Run at Lincoln Center on August 22, 2010", Broadway.com, February 18, 2010, accessed May 4, 2010

- ↑ South Pacific, Playbill.com, accessed June 18, 2012

- ↑ Fick, David. "South Pacific Review Roundup", Musical Cyberspace, February 6, 2010

- ↑ Brantley, Ben. "Optimist Awash in the Tropics", The New York Times, April 4, 2008, accessed May 25, 2013

- ↑ Hinckley, David. "It's not the same as being in Lincoln Center, but TV production of South Pacific is a can't-miss", New York Daily News, August 18, 2010, accessed May 25, 2013