South Carolina-class battleship

Michigan at the Brooklyn Navy Yard off New York. Photograph courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

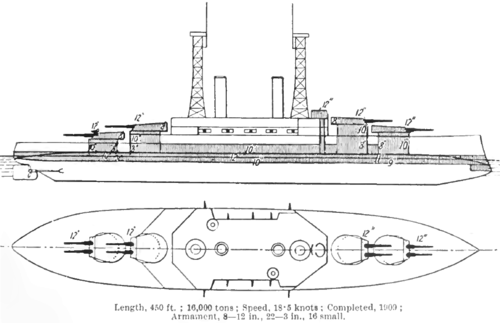

The South Carolina class, also known as the Michigan class, consisted of two battleships built in the early years of the twentieth century, South Carolina and Michigan (named after two US states). They were the first US dreadnoughts, powerful battleships with "all-big-gun" armaments whose capabilities far outstripped those of the world's older battleships.

In the opening years of the twentieth century, the prevailing theory of naval combat was that battles would continue to be fought at relatively close range using many small, fast-firing guns. Each of the ships in the previous battleship class (the Connecticut class) had many medium-sized weapons along with four large guns. American naval theorists, led by H.C. Poundstone, began to believe that a ship mounting a homogeneous battery of large guns would be more effective in battle.

As this idea began to enjoy wide acceptance, the US Congress authorized the country's navy to construct two small 16,000-long-ton (16,000 t) battleships, roughly the same size as the Connecticut class and at least 2,000 long tons (2,000 t) smaller than the foreign standard. The solution to this was found in an ambitious design drawn up by Washington L. Capps, the chief of the navy's Bureau of Construction and Repair. His plan featured the heavy armament favored by naval theorists and relatively thick armor, but respected the mandated limited displacement and provided only mediocre speed.

During construction, South Carolina and Michigan were considered to herald a new epoch in warship design, but they were soon surpassed by ever-larger vessels—including super-dreadnoughts, which began entering service in 1913. The class's low top speed of 18 knots (21 mph; 33 km/h), as compared to the 21 knots (24 mph; 39 km/h) standard of later American dreadnoughts, relegated them to serving with earlier pre-dreadnoughts during the First World War. Afterwards, both South Carolinas were scrapped with the signing of the Washington Naval Treaty.

Background

In 1901, the US Navy's battleship designs reflected the prevailing theory of naval combat—that battles would initially be fought at some distance, but the ships would then approach to close range for the final blows, when the shorter-range, faster-firing guns would prove most useful. Its premier battleship class under construction carried four large 12-inch (305 mm), eight 8-inch (203 mm), and twelve 7-inch (178 mm) guns, a striking power only slightly heavier than typical foreign battleships of the time.[3]

The Naval Institute's Proceedings devoted space in two of its 1902 issues to possible improvements in battleship design. The first article was authored by Lieutenant Matt H. Signor. He argued for a ship with 13-inch (330 mm) and 10-inch (254 mm) 40-caliber guns in four triple turrets, and a secondary battery of 5-inch (127 mm)/60 guns. While this paper alone did not sway the Navy's designers, it provoked enough thought that Proceedings published comments on the story from Captain W.M. Folger, Professor P.R. Alger and David W. Taylor, the former the foremost gunnery expert in the Navy, the latter an up-and-coming officer and future chief constructor. These comments expressed doubt that the proposed vessel could be modified into a feasible design, but they praised his thoughts as going in the right direction. Alger believed that Signor was on the right track in making the armament larger, though he thought that triple turrets would be unworkable and eight 12-inch guns in four twin turrets would be a much better arrangement. Naval historian Norman Friedman believes that this was one of the "earliest serious proposals for a homogeneous big-gun battery."[4]

The suggestion that led directly to the South Carolina class came from H.C. Poundstone, a Lieutenant Commander in the Navy, who would become the principal proponent of an American all-big-gun design. In a December 1902 paper written for President Theodore Roosevelt, he presented an argument for greatly increasing the size of current battleships, although he also believed that the mixed main batteries should be retained. By the time this was published in the 1903 March and June editions of Proceedings, Poundstone had begun advocating an all-big-gun arrangement featuring twelve 11-inch guns mounted on a 19,330-long-ton (19,640 t) ship. In October of the same year, the Italian naval architect Vittorio Cuniberti presented a similar idea in an article for Jane's Fighting Ships entitled "An Ideal Battleship for the British Navy". He argued in favor of a ship with twelve 12-inch guns on a slightly larger displacement than the battleships in service at the time, 17,000 long tons (17,000 t). He believed that the higher weight would allow 12 inches of armor and machinery capable of propelling the ship at 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph). Poundstone used what he believed to be the great popularity for this idea among Europeans to justify the all-big-gun design.[5]

In 1903, Poundstone's designs began receiving attention from American naval authorities. After being refined by Washington Irving Chambers, Poundstone's work was brought to the Naval War College, where it was tested in war games during the 1903 Newport Conference. Results from these indicated that a theoretical battleship that dispensed with the intermediate eight- and seven-inch armament and was armed with only twelve 11- or 12-inch guns, all able to fire on a single broadside, was worth three of the battleships then in service. The main reasoning for this, according to the men who conducted the tests, was that the measure of effective gun ranges was directly related to the maximum length of an enemy's torpedo range. At this time, the latter was roughly 3,000 yards (2,700 m); at that distance, the seven- and eight-inch guns common to American intermediate batteries would not be able to penetrate the armor of enemy battleships. Worse still, it was certain that—as the United States was developing a 4,000-yard (3,700 m) torpedo—gun range would have to rise in the near future, making the intermediate guns even less useful. However, a homogeneous main battery of 11- or 12-inch guns would be able to penetrate the armor and had sufficient explosive power to disable an enemy capital ship, and adding as many three-inch (76 mm) guns as possible would provide a strong defense against destroyers.[6]

Design

Faced with this evidence, the General Board formally requested that the Bureau of Construction and Repair (C&R) draw up plans for a battleship including these characteristics in October 1903, but no progress had been made by 26 January 1904, when the General Board asked C&R for a design including four 12-inch guns, eight 10-inch or larger guns, and no intermediate armament beyond 3-inch anti-destroyer guns. The move to 10-inch weaponry was the result of doubt among naval authorities that heavier guns could physically be mounted on a ship's broadside. No action was taken on this request until September, when C&R began planning a ship with four 12-inch guns in dual turrets along with eight dual 10-inch or four single 12-inch guns.[6]

Meanwhile, the Naval War College played three battleship designs against each other at its 1904 Newport Conference; the ships that had resulted from the 1903 conference, the new C&R design from September, and the latest battleships under construction, the Connecticut class. The 7- and 8-inch guns, and even the 10-inch guns, were demonstrated again to be unsatisfactory; hitting a battleship at the ideal angle of 90° to its belt, they could pierce only 12 inches of Krupp armor, not enough to counter enemy capital ships. Speed calculations were also done at this time which showed that even a 3-knot (3.5 mph; 5.6 km/h) advantage over an enemy fleet would be inconsequential to the final outcome of almost all naval battles—the slower ships could stay within range by turning on a tighter radius.[7]

Early in [the 20th century], several navies simultaneously decided to shift to a main battery composed entirely of the heaviest guns. The first and most famous product of this innovation was HMS Dreadnought, which gave her name to a generation of all-big-gun ships. Parallel to but independent of her conception was the American South Carolina, in many ways equally revolutionary. She introduced a superfiring main battery, a design economy which gave her a better-protected broadside equal to that of her British contemporary on about 3,000 [long] tons less displacement. (Norman Friedman, U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History [Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1985], 51)

Within the naval bureaus, however, there was still much resistance. In mid-to-late 1904, Poundstone continued to lobby the General Board while C&R protested that the final determinant in a naval battleship would be the light guns and in any case such a large uniform battery was not feasible. Poundstone replied with a design of his own creation, USS Possible, which fit twelve 11-inch (280-millimetre) guns on a ship of 19,330 long tons (19,640 tonnes).[upper-alpha 2] With support from Lieutenant Commander William Sims, who was able to cite the increasingly accurate long-gunnery of the Navy, and interest shown in the project by President Roosevelt, the bureaucratic stalling was ended.[8]

On 3 March 1905, Congress passed a bill which authorized the Navy to construct two new battleships which would be named after the states of South Carolina and Michigan. The maximum tonnage limit was set at 16,000 long tons (16,257 tonnes), the same weight as the mixed-battery Connecticut class of two years prior, in an attempt to stem the rising displacement—and accompanying costs—of the Navy's new capital ships.[9] This provision was met with a mixed reception from naval designers. Some, including retired Admiral of the Navy George Dewey, thought the limit should have been set at a minimum of 18,000 long tons (18,289 tonnes), the standard of foreign battleships. Others believed adding a significant amount of speed or firepower, something one would expect with an increase in tonnage, would require a much larger size than 18,000 tons. They argued, then, that the increase in size would buy nothing more than an increased target profile.[10]

The Constructor of the Navy, Washington L. Capps, devised an ambitious design that could pack powerful armament and thick armor onto the small hull. He believed that future naval battles would involve fleets rather than single-ship actions, and so while the wing turrets so common in European designs were useful in the latter role for putting a maximum amount of firepower in any given direction, they were less so while operating as part of a line of battle. From this, Capps theorized that the principal concern of battleships was how much shell weight they could fire per broadside. The arrangement of superfiring turrets on the centerline would allow the hull to be as short as possible while still having the most powerful broadside possible.[9][upper-alpha 3]

As the superfiring arrangement used a great amount of space within each ship, Capps was forced to economize in other ways to stay within the tonnage limit, but the need to cut the ship down one deck created problems with volume. Machinery had to be built smaller than normal to fit in the space between the fore and aft magazines, both of which were larger than usual. Boiler rooms were moved inboard to make room for torpedo protection. The biggest drawback was in propulsion: there was no room for engines that could provide the same amount of power as on previous battleships. Capps suggested cutting down the number of boilers by one-third to make room; it may have been at this point that he considered turbine propulsion, for which he would have needed the extra room. All the Bureau of Engineering could offer in response was more compact boiler rooms by eliminating centerline bulkheads. The end result was that the South Carolina class fell behind HMS Dreadnought in top speed.[11]

Specifications

At a design displacement of 16,000 long tons (16,257 t), the South Carolina class dreadnoughts were the same size as their Connecticut class pre-dreadnought predecessors. In service, they could actually be lighter: Louisiana came out to a standard displacement of 15,272 long tons (15,517 t), while Michigan was only 14,891 long tons (15,130 t) by the same measurement. The South Carolina class's hull size was also comparable to the earlier ships, with a length of 452 feet 9 inches (138 m) overall, 450 feet (137 m) between perpendiculars, and the same at the waterline. Their beam was 80 feet 2.5 inches (24 m), and their draft was 34 feet 6.5 inches (11 m). The South Carolina class's metacentric height was 6.9 feet (2 m) normally and 6.3 feet (2 m) at full load. Only the South Carolina class's beam and metacentric height were greater than on the Connecticuts.[12]

The South Carolinas had a propulsion system consisting of two vertical triple expansion engines driving two three-bladed propellers. These were in turn powered by twelve coal-fired superheating Babcock & Wilcox water-tube boilers located in three watertight compartments. Together, they weighed 1,555.308 long tons (1,580 t), which was just over the specified contract limit. The traditional triple expansion engines were installed rather than the steam turbines used in the British Dreadnought. The actual coal capacity of the South Carolinas was 2,374.2 long tons (2,412 t) at full load, slightly more than the designed maximum of 2,200 long tons (2,235 t), and this allowed for an endurance of 6,950 nautical miles (7,998 mi; 12,871 km) at 10 knots (12 mph; 19 km/h). While both ships were able to surpass 20 knots (23 mph; 37 km/h) in idealized trial conditions, in normal conditions top speeds of 18.5 knots (21 mph; 34 km/h) were expected.[13]

The class's main battery consisted of eight 12-inch (305 mm)/45 caliber Mark 5 guns in four turrets, one pair fore and one aft, with 100 rounds for each gun. The guns were placed in an innovative superfiring arrangement, where one turret was mounted slightly behind and above the other. This arrangement meant that the shortcomings of other all-big-gun arrangements, such as the torsional stress and rolling inertia from wing turrets, were avoided. The anti-torpedo-boat secondary armament of twenty-two 3-inch (76 mm) guns was mounted in casemates.[14]

Armor on the South Carolina class was described by naval author Siegfried Breyer as "remarkably progressive", despite deficiencies in horizontal and underwater protection. The belt was thicker over the magazines, 12 to 10 inches (305 to 254 mm), than over the propulsion, 11 to 9 inches (279 to 229 mm), and in front of the forward magazines, 10 to 8 inches (254 to 203 mm). Casemate armor was the same, 10-to-8 inches, while the deck armor varied from 100 to 40 pounds.[upper-alpha 1] The turrets and conning tower had the heaviest armor, with 12–8–2.5 in (face/side/roof; 305–203–63.5 mm) and 12 to 2 inches (305 to 51 mm). The barbettes were protected with 10 to 8 in of armor. The total weight of the armor amounted to 31.4% of the design displacement, slightly more than the next three battleship classes had.[15]

Ships

| Ship | Builder | Laid down | Launched | Commissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Carolina | William Cramp and Sons | 18 December 1906 | 11 July 1908 | 1 March 1910 | Broken up as a result of the Washington Naval Treaty, 1920s |

| Michigan | New York Shipbuilding Corporation | 17 December 1906 | 26 May 1908 | 4 January 1910 |

Construction and trials

The contracts for Michigan and South Carolina were awarded on 20 and 21 July, respectively. Michigan's keel was laid down on 17 December 1906, one day before South Carolina's. After the initial construction periods, the ships were launched on 26 May and 11 July 1908.[16] Michigan was also more than half complete when launched, and the ship was christened by Carol Newberry, the daughter of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Truman Handy Newberry. The warship was billed as epoch-making, and the spectacle included many prominent individuals, including the governor and lieutenant-governor of Michigan, the governor of New Jersey, the mayor of Detroit, and the secretary of the Interior Department, along with many naval admirals and constructors.[17] South Carolina's launch, taking place just after noon, was attended by many notable residents of the state of South Carolina, including Governor Martin Frederick Ansel. His daughter Frederica christened the ship, which was 51.9 percent complete at the time.[18]

The two ships then entered the fitting-out stage, and were completed in all respects. Before being commissioned as active-duty warships, they were put through sea trials to ensure they met their contracted specifications,[16] including traveling at 18.5 knots (21.3 mph; 34.3 km/h) or more for four straight hours, and being driven at 12 knots (14 mph; 22 km/h) and 17.5 knots (20.1 mph; 32.4 km/h) for twenty-four hours to test the machinery performance and coal consumption.[19]

Michigan's trials were originally conducted at the navy's traditional testing grounds off Rockland, Maine beginning on 9 June 1909. Standardization trials were completed on a marked course off Monhegan Island, with the ship reaching a maximum speed of 20.06 knots (23.08 mph; 37.15 km/h) and an average of 19.11 knots (21.99 mph; 35.39 km/h). On 10 June, the four-hour run was completed. This was immediately followed with the twenty-four hour 17-knot run, but they were forced to stop only a few hours in to fix a malfunctioning relief valve. During this time, a heavy fog rolled in, and Michigan ran aground on a sand bar that night near Cape Cod Light due to the reduced visibility. After being cleaned, the ship attempted the twenty-four hour 12-knot run on the 12th, but it was called off when a damaged propeller blade made the starboard engine run at 1,000 horsepower more than the other. Michigan was forced to put in at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, where it was found that both propellers were damaged. It took more than a month to replace them; beginning on 20 July, Michigan sailed to the Delaware Capes to complete its trials. These included additional standardization runs (21 July), the twenty-four hour 17.5-knot run (22 July), and the twenty-four hour 12-knot run (24 July).[20] Michigan was then commissioned on 4 January 1910—making the United States the third country to have a dreadnought in commission, behind the United Kingdom and Germany but just ahead of Brazil—and its shakedown cruise lasted until 7 June.[21]

South Carolina's trials were done off the Delaware Capes beginning on 24 August 1909; its standardization runs gave an average speed of 19.25 knots (22.15 mph; 35.65 km/h) and a top speed of 20.52 knots (23.61 mph; 38.00 km/h). The next morning, the four-hour full-speed trial was successfully completed, with a maximum speed of 18.88 knots (21.73 mph; 34.97 km/h). After the trials were complete, the ship returned to William Cramp for final modifications.[22] South Carolina was then commissioned on 1 March 1910 and departed for a shakedown cruise six days later.[23]

Service history

After being commissioned, both ships were placed into the US Atlantic Fleet. Both ships operated up and down the American east coast from July until November. On 2 November, as part of the Second Battleship Division, the two ships left the Boston Navy Yard for a training voyage to Europe, where they visited the Isle of Portland in the United Kingdom and Cherbourg in France. In January 1911, they returned to the US naval base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba before continuing to another base in Norfolk. After further maneuvers, the ships split up; Michigan remained on the east coast, while South Carolina departed on another trip to Europe. The ship visited Copenhagen (Denmark), Stockholm (Sweden), Kronstadt (Russia), and Kiel (Germany)—the last during Kieler Woche, a large sailing event—before returning in July 1911.[24]

South Carolina next took part in the naval review in New York, before several months of traveling to ports on the east coast, welcoming a visiting German naval squadron comprising the battlecruiser SMS Moltke and two light cruisers, and a three-month overhaul in Norfolk. South Carolina then joined Michigan to visit Pensacola, New Orleans, Galveston, and Vera Cruz in Mexico, as part of the Special Service Squadron. South Carolina later visited Colon, Panama in January 1913. Both ships continued their previous service of visiting east coast ports before unrest in Mexico and the Caribbean caused the American government to order them away. South Carolina landed marines on Haiti on 28 January to protect the American delegation there. They returned to the ship when Oreste Zamor took power, but continued unrest later led the United States to occupy Haiti. South Carolina then joined Michigan at Vera Cruz while the United States occupied that city.[24]

At the beginning of the First World War, both of the South Carolina-class battleships were grouped with two older pre-dreadnoughts (Vermont and Connecticut) due to their top speeds, which were lower than the later Standard-type battleships. South Carolina was refitted in Philadelphia between 14 October and 20 February 1915, and both ships were kept on neutrality patrols off the eastern seaboard. After the United States entered the war on 6 April 1917, the ships were largely kept on the American side of the Atlantic. In January 1918, Michigan was training with the main fleet when they traveled through a strong storm. The high winds and waves caused its forward cage mast to collapse, killing six and injuring thirteen.[25]

On 6 September 1918, South Carolina escorted a fast convoy partway across the Atlantic, becoming the first American battleship (alongside New Hampshire and Kansas) to do so. When returning to the United States, South Carolina lost its starboard propeller. When continuing with the port propeller, a valve in its engine malfunctioned; continuing with an auxiliary valve caused a large amount of vibration, so the ship was stopped just hours later for temporary repairs on the main valve before continuing to the Philadelphia Naval Yard for repairs. Michigan had the same problem when escorting a convoy in the next month; the ship lost its port propeller on 8 October, but managed to return home on 11 October without further incident.[26]

With the war's end on 11 November 1918, the South Carolina-class battleships were used to repatriate American soldiers that had been fighting in the war.[27] The idea for using battleships in a similar role—that of transporting troops to the war zone—was actually proposed by South Carolina's executive officer in early 1918, but was not taken up:

Nearly half a million tons of shipping, built for a military purpose, aging rapidly in a military sense and doomed to early obsolescence, is occupying a passive role in the greatest war in history. I submit simply that this tonnage should be put to a military use ... If our battleships cannot actively engage the enemy and are not needed to contain the enemy, it is essential, in order that their role may be an active one, that they bring pressure to bear upon the enemy by projecting man power within striking distance of the battle front. (C.S. Freemen to Daniels, "War Use for Battleships," memorandum, 28 January 1918, OB File, RG 45, in Jerry W. Jones, U.S. Battleship Operations in World War I [Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1998], 120)

In the years after the war, the two battleships were used for training cruises. When the Washington Naval Treaty was signed in February 1922, the class was slated for disposal under its provisions. South Carolina was sold for scrapping on 24 April 1924, and both it and Michigan were broken up in the Philadelphia Navy Yard.[24]

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 40 pounds is about one inch or 25 millimeters.[3]

- ↑ Full specifications for Possible included:[1]

- Displacement: 19,330 long tons (19,640 tonnes)

- Length: 500 feet (150 metres)

- Beam: 81 feet (25 metres)

- Draft: 25 feet (7.6 metres)

- Freeboard: 20 feet (6.1 metres)

- Main battery: twelve 11-inch (280-millimetre)/50 caliber guns

- Secondary/intermediate battery: none

- Anti-destroyer weaponry: forty 3-inch (76-millimetre)/50 caliber guns

- Torpedo tubes: 6

- Belt armor: depending on the location, 4-6-8-10 (102-152-203-254 mm)

- Upper belt: 9 inches (230 millimetres)

- Turret armor: 11 inches

- Deck armor: 1.5 to 3 inches (38 to 76 millimetres)

- Speed: 18 knots (21 mph; 33 km/h)

- ↑ A ship with all turrets on the centerline can focus the same amount of fire to port or starboard during a broadside. This is juxtaposed against wing turrets, which are located to the left or right of a ship's superstructure. It is hard to pinpoint an exact date as to when the superfiring idea was adopted. There were many all-big-gun plans, but only an index of them survives. Friedman speculates that the superfiring arrangement may have been accepted by the various bureaus by April 1905, giving as evidence a memo from Capps to the Bureau of Engineering asking for smaller engineering spaces in order "to increase the main battery." The design as a whole was finalized on 26 June 1905, though it took until mid-1906 to mail it to shipyards to begin the bidding process.[2]

Endnotes

- ↑ Dinger, "U.S.S. South Carolina," 200.

- ↑ Leavitt, "U.S.S. Michigan," 915.

- ↑ Campbell, "United States of America: 'The New Navy', 1883–1905," 137–38, 143; Friedman, U.S. Battleships, 52.

- ↑ Friedman, U.S. Battleships, 51; Signor, "A New Type of Battleship"; Folger, Alger, Taylor, "Discussion".

- ↑ Friedman, U.S. Battleships, 52; Cuniberti, "An Ideal Battleship"; Friedman, "The South Carolina Sisters," Poundstone, "Size of Battleships for U.S. Navy," 161–174.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Friedman, U.S. Battleships, 53; Friedman, "The South Carolina Sisters".

- ↑ Friedman, U.S. Battleships, 53–54.

- ↑ Friedman, U.S. Battleships, 54–55.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Friedman, U.S. Battleships, 55; Friedman, "South Carolina Sisters".

- ↑ "Dispute over Battleships," New York Times, 16 October 1905.

- ↑ Breyer, Battleships and battle cruisers, 196; Friedman, U.S. Battleships, 57.

- ↑ Friedman, U.S. Battleships, 430–32; Leavitt, "U.S.S. Michigan," 932.

- ↑ Friedman, U.S. Battleships, 431–32; Breyer, Battleships, 196; Leavitt, "U.S.S. Michigan," 941–43.

- ↑ Friedman, U.S. Battleships, 431, Friedman, Battleship Design, 133–34.

- ↑ Friedman, U.S. Battleships, 431; Friedman, Battleship Design, 166–67.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Leavitt, "U.S.S. Michigan," 915; Dinger, "U.S.S. South Carolina, 200.

- ↑ "The Michigan," Navy (Washington, DC), 26; "Launching the Navy's 'All-Big-Gun' Battleship," Harper's Weekly, 30.

- ↑ "The South Carolina Launched," Navy (Washington, DC), 35–36; "The Battleship South Carolina," International Marine Engineering, 401; "New All Big Gun Warship Launched," New York Times, 12 July 1908.

- ↑ Leavitt, "U.S.S. Michigan," 915; Dinger, "U.S.S. South Carolina," 228.

- ↑ Leavitt, "U.S.S. Michigan," 915–17.

- ↑ "Michigan," Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

- ↑ Dinger, "U.S.S. South Carolina," 228, 234; "Fastest Ship of Her Class," New York Times, 29 August 1909.

- ↑ "South Carolina," Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "South Carolina" and "Michigan," Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

- ↑ Jones, Battleship Operations, 110; "South Carolina" and "Michigan," Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

- ↑ Jones, Battleship Operations, 118–19.

- ↑ Jones, Battleship Operations, 120.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to South Carolina class battleships. |

- Books

- Breyer, Siegfried. Battleships and Battle Cruisers, 1905–1970. Translated by Alfred Kurti. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1973. OCLC 702840.

- Campbell, N.J.M. "United States of America: 'The New Navy'." In Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway's Maritime Press, 1979. ISBN 0-85177-133-5. OCLC 5834247.

- Friedman, Norman. Battleship Design and Development, 1905–1945. New York: Mayflower Books, 1978. ISBN 0-8317-0700-3. OCLC 4505348.

- ———. U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1985. ISBN 0-87021-715-1. OCLC 12214729.

- Jones, Jerry W. U.S. Battleship Operations in World War I. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1998. ISBN 1-55750-411-3. OCLC 37935228.

- Journal articles

- Cuniberti, Vittorio. "An Ideal Battleship for the British Fleet," in Jane, Fred T., ed. All The World's Fighting Ships. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co., 1903.

- Dinger, H.C. "U.S.S. South Carolina: Description and Official Trials." Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers 22, no. 3 (1910): 200–38.

- Folger, W.M.; Alger, Philip R.; Taylor, D.W. "Discussion; A New Type of Battleship." Proceedings of United States Naval Institute 28, no. 2 (1902): 269–275.

- Friedman, Norman. "The South Carolina Sisters: America's First Dreadnoughts." Naval History 24, no. 1 (2010): 16–23.

- "Launching the Navy's 'All-Big-Gun' Battleship." Harper's Weekly 52, no. 2687 (1908): 30.

- Leavitt, William Ashley. "U.S.S. Michigan: Description and Official Trials." Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers 21, no. 3 (1909): 915–71.

- Poundstone, Homer C. "Size of Battleships for U.S. Navy." Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute 29, no. 1 (1903): 161–174.

- Signor, Matt H. "A New Type of Battleship." Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute 28, no. 1 (1902): 1–20.

- "The Battleship South Carolina." International Marine Engineering 13, no. 9 (1908): 401.

- "The South Carolina Launched." Navy (Washington, DC) 2, no. 7 (1908): 35–36.

- "The Michigan." Navy (Washington, DC) 2, no. 6 (1908): 26–29.

- Official sources

- "Michigan." Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command.

- "South Carolina." Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command.

External links

| |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||