Solid South

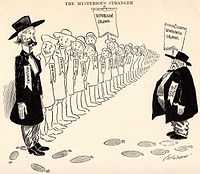

The term Solid South describes the electoral support of the Southern United States for Democratic Party candidates from 1877 (the end of Reconstruction) to 1964 (the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964). During this time, the vast majority of local and state officeholders in the South were Democrats, as were federal politicians the region sent to Washington, D.C.. The virtual non-existence of the Republican Party in the region meant that a candidate's victory in Democratic primary elections was tantamount to election to the office itself.

The Democratic dominance of the South originated in many white Southerners' animosity towards the Republican Party's stance in favor of political rights for blacks during Reconstruction and Republican economic policies such as the high tariff and the support for continuing the gold standard, both of which were seen as benefiting Northern industrial interests at the expense of the agrarian South in the 19th century. It was maintained by the Democratic Party's willingness to back Jim Crow laws and racial segregation.[1]

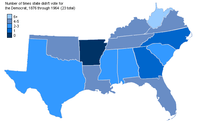

Democrats won by large margins in the region in every presidential election from 1876 to 1948 except for 1928, when candidate Al Smith, a Catholic and a New Yorker, ran on the Democratic ticket; even in that election, the divided South provided Smith with nearly three-fourths of his electoral votes. Beginning in about 1948, the national Democratic Party's support of the civil rights movement significantly reduced Southern support for the Democratic Party and allowed the Republican Party to make gains in the South. In 1968, President Nixon's "Southern Strategy" is credited with allowing either the Republicans or Democrat George Wallace's independent campaign to keep much of the South out of the Democratic column at the presidential level. The South continued to send an overwhelmingly Democratic delegation to Congress until the Republican Revolution of 1994. Today, the South is considered a Republican stronghold at all levels above the local level, with Republicans holding majorities in every state except Arkansas and Kentucky after 2010. Political experts have often cited a southernization of politics following the fall of the Solid South.

Democratic factionalization over the Civil Rights Movement

The "Solid South" is today usually defined as the eleven states of the old Confederacy plus Kentucky, Oklahoma, and West Virginia. Missouri was also included in the original Solid South although since the early 1900s Missouri has been seen as a Midwestern bellwether state mostly because Missouri is classified as a Midwestern State by the U.S. Census. West Virginia experienced wide voter disfranchisement after the Civil War and Republicans controlled the state until 1872, when ex-Confederate proscription was lifted.[2] The Democrats carried the state for a generation and wrote a new constitution, and by the 1930s West Virginia was completely identified with the South. Oklahoma was not included originally with the Solid South as it has only voted in Presidential elections since 1908 but Oklahoma's voting history mirrors the Solid South only going Republican after the Civil Rights era began in the 1940s. Maryland and Delaware are classified by the U.S. Census as Southern States however only Maryland was occasionally classified with the Solid South.

The Solid South had already begun to erode in the 1890s. William Jennings Bryan's western populist movement had split the Democratic Party between the old guard Bourbon Democrats and the Progressives. The split allowed McKinley to win Kentucky by 277 votes out of 445,928 votes cast. Maryland went for William McKinley by a margin of 32,809 votes out of 250,249 votes cast. In 1904, Missouri would bolt the Solid South to support Roosevelt while Maryland in a controversial election reminscient of the 2000 Florida election would award the state to Alton Parker, despite Roosevelt winning by 51 votes.[3]

The 1920 election was a referendum on President Woodrow Wilson's League of Nations. Pro-isolation sentiment in the South would benefit Republican Warren G.Harding who would go on to win Tennessee and Missouri. In 1924, Coolidge would win Kentucky and Missouri. In 1928, Hoover, perhaps benefiting from bias against his Roman Catholic Anti-Prohibition opponent Al Smith, won not only Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee, but also Florida, North Carolina, Texas, and Virginia. Maryland defected to the Republicans in the 1920s and would not vote Democratic again until Franklin Delano Roosevelt's 1932 Presidential landslide over Republican President Herbert Hoover.

The South appeared "solid" again during the period of Franklin D. Roosevelt's political dominance, but cracks began to appear in the following administration. Democratic President Harry S. Truman's support of the civil rights movement, combined with the adoption of a civil rights plank in the 1948 Democratic platform, prompted many Southerners to walk out of the Democratic National Convention and form the Dixiecrat Party. This splinter party played a significant role in the 1948 election; the Dixiecrat candidate, Strom Thurmond, carried Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. In the elections of 1952 and 1956, the popular Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower carried several southern states, with especially strong showings in the new suburbs. In 1956, Eisenhower also carried Louisiana, becoming the first Republican to win the state since Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, but the rest of the Deep South was still a bastion for Eisenhower's Democratic opponent, Adlai Stevenson. The 1948 election also marked Maryland's permanent defection from the Solid South as the expansion of the federal government led to a population explosion in the state that changed Maryland politically into a Northeastern State.

In the 1960 election, the Democratic nominee, John F. Kennedy, continued his party's tradition of selecting a Southerner as the vice presidential candidate (in this case, Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas). Kennedy and Johnson, however, supported civil rights. In October 1960, when Martin Luther King, Jr. was arrested at a peaceful sit-in in Atlanta, Georgia, Kennedy placed a sympathetic phone call to King's wife, Coretta Scott King, and Robert Kennedy helped secure King's release. King expressed his appreciation for these calls. Although King himself made no endorsement, his father, who had previously endorsed Republican Richard Nixon, switched his support to Kennedy.

Because of these and other events, the Democrats lost ground with white voters in the South, as those same voters increasingly lost control over what was once a whites-only Democratic Party in much of the South. The 1960 election was the first in which a Republican presidential candidate received electoral votes in the South while losing nationally. Nixon carried Virginia, Tennessee, and Florida. Though Kennedy also won Alabama and Mississippi. slates of unpledged electors, representing Democratic segregationists, would award the states' electoral votes to Harry Byrd.

The parties' positions on civil rights continued to evolve in the run up to the 1964 election. The Democratic candidate, Johnson, who had become president after Kennedy's assassination, spared no effort to win passage of a strong Civil Rights Act. After signing the landmark legislation, Johnson said to his aide, Bill Moyers; "I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come."[4] In contrast, Johnson's Republican opponent, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964, believing it enhanced the federal government and infringed on the private property rights of businessmen. Goldwater did support civil rights in general and universal suffrage, and voted for the 1957 and 1960 Civil Rights Acts as well as the 24th Amendment, which banned poll tax as a requirement for voting. He was a member of the NAACP.[citation needed]

That November, Johnson won a landslide electoral victory, and the Republicans suffered significant losses in Congress. Goldwater, however, besides carrying his home state of Arizona, carried the Deep South: Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina had switched parties for the first time since Reconstruction. Goldwater notably won only in southern states that had voted against Republican Richard Nixon in 1960, while not winning a single state that Nixon had carried, a complete inversion of the electoral pattern of the last presidential election. Prior to 1956, the region had almost always provided the only victories for Democratic challengers to popular Republican incumbent presidents. Now, however, the South had provided a Republican challenger with electoral victories against a popular Democratic incumbent.

"Southern Strategy": End of Solid South

In the 1968 election, the Republican candidate, Richard Nixon, saw this trend and capitalized on it with his "Southern strategy." The new method of campaigning was designed to appeal to white Southerners who were more conservative than the national Democratic Party. As a result of the strategy, the Democratic candidate, Hubert Humphrey, was almost shut out in the South; he carried only Texas, the rest of the region being divided between Nixon and the American Independent Party candidate George C. Wallace, the governor of Alabama, who had gained fame for opposing integration. Nationwide, Nixon won a decisive Electoral College victory, although he received only a plurality of the popular vote.

After Nixon's landslide re-election in 1972, the election of Jimmy Carter, a southern governor, gave Democrats a short-lived comeback in the South (winning every state in the Old Confederacy except for Virginia, which was narrowly lost) in 1976, but in his unsuccessful re-election bid in 1980, the only Southern states he won were his native state of Georgia and West Virginia. The year 1976 was the last year a Democratic presidential candidate won a majority of Southern electoral votes. The Republicans took all the region's electoral votes in 1984 and every state except West Virginia in 1988.

In 1977, political scientist Larry Sabato analyzed the rise of two-party politics in the Southern United States, particularly with his 1977 publication of The Democratic Party Primary in Virginia: Tantamount to Election No Longer.[5] See also tantamount to election.

In 1992 and 1996, when the Democratic ticket consisted of two Southerners, (Bill Clinton and Al Gore), the Democrats and Republicans split the region. In both elections, Clinton won Arkansas, Louisiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia, while the Republican won Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia. Bill Clinton won Georgia in 1992, but lost it in 1996 to Bob Dole. Conversely, Clinton lost Florida in 1992 to George Bush, but won it in 1996.

In 2000, however, Gore received no electoral votes from the South, even from his home state of Tennessee, but the popular vote in Florida was extraordinarily close in awarding the state's electoral votes to George W. Bush. This pattern continued in the 2004 election; the Democratic ticket of John Kerry and John Edwards received no electoral votes from the South, even though Edwards was from North Carolina, and was born in South Carolina. However, in the 2008 election, Barack Obama won the former Republican strongholds of Virginia and North Carolina as well as Florida; Obama won Virginia and Florida again in 2012 and lost North Carolina by only 2.04%.

While the South was shifting from the Democrats to the Republicans, the Northeastern United States went the other way. The Northeastern United States is defined by the US Census Bureau as Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and the New England States although politically the Northeast also includes Maryland and Delaware. Well into the 1980s, the Northeast was a bastion of the Republican Party. The Democratic Party made steady gains there, however, and in 1992, 1996, 2004, 2008 and 2012 all eleven Northeastern states, from Maryland to Maine, voted for the Democrats. The same trend can be observed on the West Coast and Upper Midwest (excluding The Dakotas and including Illinois and Iowa) of the nation, as they shifted from solidly Republican and swing-states, respectively, to a change in political party strength.

"Southern strategy" today

Today, the South has a mix of Republican and Democratic officeholders (Senators, Representatives and state governors). In presidential elections, however, the region is a Republican stronghold. During the 2010 midterm elections, Republicans swept the South, successfully reelecting every Senate incumbent and electing freshmen Marco Rubio in Florida and Rand Paul in Kentucky. In the House, Republicans reelected every incumbent except for Joseph Cao of New Orleans and defeated several Democratic incumbents. Republicans are now the majority in the congressional delegations of every Southern state. Every Solid South state, with the exception of Arkansas, elected or reelected Republicans governors. Most significantly, Republicans took control of both houses of the Alabama and North Carolina state legislatures for the first time since Reconstruction. Even in Arkansas, the GOP won three of six statewide down-ballot positions for which they had often not fielded candidates until recently; they also went from eight to 15 out of 35 seats in the state senate and from 28 to 45 out of 100 in the state house of representatives. In 2012, the Republicans finally took control of the Arkansas state legislature, leaving West Virginia as the last Solid South state with the Democrats still in control of the state legislature. Many analysts believe the so-called "Southern Strategy," that has been employed by Republicans since the 1960s is now complete, with Republicans in firm, almost total, control of political offices in the South. However, recent changes in demographics may cause the "Solid South" to break apart again; for example, the defense industry in Virginia has caused the state to flip from Republican to Democratic in the last two presidential elections, while North Carolina was extremely close between both parties in both the 2008 and 2012 elections.

South in Presidential elections

While Republicans occasionally won southern states in elections in which they won the presidency in the Solid South, it was not until 1960 that a Republican carried one of these states while losing the national election.

- Key

| Democratic Party nominee |

| Republican Party nominee |

| Third-party nominee or write-in candidate |

Bold denotes candidates elected as president

South in gubernatorial elections

Officials who acted as governor for less than ninety days are excluded from this chart. This chart is intended to be a visual exposition of party strength in the solid south and the dates listed are not exactly precise. Governors not elected in their own right are listed in italics.

The parties are as follows: Democratic (D), Farmers' Alliance (FA), Prohibition (P), Readjuster (RA), Republican (R).

References

- ↑ Connie Rice: Top 10 Election Myths to Get Rid Of : NPR The situation in Louisiana was an example--see John N. Pharr, Regular Democratic Organization#Reconstruction & aftermath, and the note to Murphy J. Foster (who served as governor of Louisiana from 1892 to 1900).

- ↑ Herbert, Hilary, Why the Solid South?, R.H. Woodward & Co., Baltimore, 1890, pgs. 258-284.

- ↑ Too Close to Call: Presidential Electors and Elections in Maryland, featuring the Presidential Election of 1904. Archives of Maryland Documents for the Classroom.

- ↑ Second Thoughts: Reflections on the Great Society New Perspectives Quarterly, Winter 1987

- ↑ Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1977, ISBN 0-8139-0726-8 and ISBN 978-0-8139-0726-0.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Electoral votes awarded by the Electoral Commission

- ↑ Oklahoma was not a state until 1907 and did not vote in presidential elections until 1908

- ↑ Five of Alabama's electoral votes went to John F. Kennedy.

- ↑ One North Carolina Republican elector switched his vote to Wallace.

- ↑ Since both the Governor and Lieutenant Governor had been impeached, the former resigning and the latter being removed from office, Stone, as president of the Senate, was next in line for the governorship. Filled unexpired term and was later elected in his own right.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 11.9 As lieutenant governor, filled unexpired term.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 12.9 Died in office.

- ↑ Resigned upon appointment as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury.

- ↑ Did not run for re-election in 1888, but due to the election's being disputed, remained in office until February 6, 1890.

- ↑ Elected in 1888 for a term beginning in 1891, an election dispute prevented Fleming from taking office until February 6, 1890

- ↑ William S. Taylor (R) was sworn in and assumed office, but the state legislature challenged the validity of his election, claiming ballot fraud. William Goebel (D), his challenger in the election, was shot on January 30, 1900. The next day, the legislature named Goebel governor. However, Goebel died from his wounds three days later.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 17.9 17.10 17.11 17.12 17.13 As lieutenant governor, acted as governor for unexpired term and was subsequently elected in his own right.

- ↑ As President of the state Senate, filled unexpired term and was subsequently elected in his own right.

- ↑ Gubernatorial terms were increased from two to four years during Jelks' governorship; his first term was filling out Samford's two-year term, and he was elected in 1902 for a four-year term.

- ↑ Resigned to take an elected seat in the United States Senate. Mar. 21, 1905

- ↑ As Speaker of the Senate, ascended to the governorship.

- ↑ The elected governor, Hoke Smith resigned to take his elected seat in the United States Senate. John M. Slaton, president of the senate, served as acting governor until Joseph M. Brown was elected governor in a special election.

- ↑ The elected Governor,Joseph Taylor Robinson, resigned on March 8, 1913 to take an elected seat in the United States Senate. President of the state Senate William Kavanaugh Oldham acted as governor for six days before a new Senate President was elected. Junius Marion Futrell, as the new president of the senate, acted as governor until a special election.

- ↑ Elected in a special election.

- ↑ Resigned on the initiation of impeachment proceedings. Aug. 25, 1917.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Resigned to take an elected seat in the United States Senate.

- ↑ Impeached and removed from office. Nov. 19, 1923

- ↑ Died in his third term of office. Oct. 2, 1927.

- ↑ Resigned to be a judge on the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas.

- ↑ Impeached and removed from office. Mar. 21, 1929

- ↑ As Speaker of the Senate, ascended to the governorship. Subsequently elected for two full terms.

- ↑ Paul N. Cyr was lieutenant governor under Huey Long and stated that he would succeed Long when Long left for the Senate, but Long demanded Cyr forfeit his office. King, as president of the state Senate, was elevated to lieutenant governor and later governor.

- ↑ Resigned to take an appointed seat in the United States Senate.

- ↑ Resigned upon victory in the Democratic primary for the United States Senate. Aug. 4, 1941.

- ↑ Died in office. Jul. 11, 1949

- ↑ As President of the state Senate, filled unexpired term.

- ↑ Resigned upon election to the Presidency of the United States.

- ↑ Removed from office upon being convicted of illegally using campaign and inaugural funds to pay personal debts; he was later pardoned by the state parole board based on innocence.

- ↑ Was elected as a Democrat in 1987 but switched parties to Republican in 1991.

- ↑ Resigned after being convicted of mail fraud in the Whitewater scandal.

- ↑ Resigned upon election to the Presidency of the United States. Dec. 21, 2000]]

- ↑ Resigned to take an elected seat in the U.S. Senate. Nov. 15, 2010

- ↑ Elected as Republican Party, Crist switched his registration to independent in April 2010.

- ↑ As president of the senate, served as acting governor until he won a special election in 2011.

Further reading

- Frederickson, Kari A. (2001). The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932-1968. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2594-8.

- Grantham, Dewey W. (1992). The Life and Death of the Solid South. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-0813-6.

- Herbert, Hilary Abner (1890). Why the Solid South?. R. H. Woodward & company.