Sofia

| Sofia София (Bulgarian) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| |||

|

Motto: Grows, but does not age[1] Расте, но не старее (Bulgarian) Raste, no ne staree (transliteration) | |||

Sofia | |||

| Coordinates: 42°42′N 23°20′E / 42.700°N 23.333°ECoordinates: 42°42′N 23°20′E / 42.700°N 23.333°E | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Province | Sofia-Capital | ||

| Settled by Celts | as Serdica (5th century B.C.)[2] | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor of Sofia | Yordanka Fandakova (GERB) | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 492 km2 (190 sq mi) | ||

| • Urban | 1,344 km2 (519 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 560 m (1,840 ft) | ||

| Population (2012[3][4]) | |||

| • City | 1,241,396 | ||

| • Density | 2,448/km2 (6,340/sq mi) | ||

| • Municipality | 1,301,683 | ||

| Demonym | Sofian | ||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||

| Postal code | 1000 | ||

| Area code(s) | (+359) 02 | ||

| Website | www.sofia.bg | ||

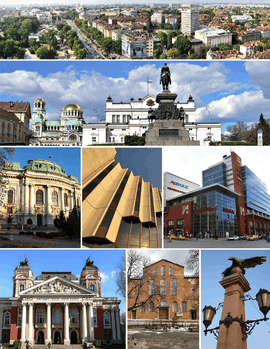

Sofia (Bulgarian: София, pronounced [ˈsɔfijɐ] (![]() )) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. Sofia is located at the foot of Mount Vitosha in the western part of the country. It occupies a strategic position at the centre of the Balkan Peninsula.[5] Sofia's history spans 2,400 years. Its ancient name Serdica derives from the local Celtic tribe of the Serdi who established the town in the 5th century BC. It remained a relatively small settlement until 1879, when it was declared the capital of Bulgaria.

)) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. Sofia is located at the foot of Mount Vitosha in the western part of the country. It occupies a strategic position at the centre of the Balkan Peninsula.[5] Sofia's history spans 2,400 years. Its ancient name Serdica derives from the local Celtic tribe of the Serdi who established the town in the 5th century BC. It remained a relatively small settlement until 1879, when it was declared the capital of Bulgaria.

Sofia is the 15th largest city in the European Union with a population of around 1.3 million people, or 1,241,396 in the city proper. According to some unoffical sources there are 2 million living and working in Sofia. [3][6]

Sofia has been ranked by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network as a Beta− city.[7] Many of the major universities, cultural institutions, and businesses of Bulgaria are concentrated in Sofia.[8]

Names

The name Serdica or Sardica (in Greek Σερδική, Σαρδική) was popular in Latin, Ancient Greek and Byzantine Greek sources from Antiquity and the Middle Ages; it was related to the local Celtic[9] tribe of the Serdi. The name was last used in the 19th century in a Bulgarian text, Service and hagiography of Saint George the New of Sofia: ВЪ САРДАКІИ.

Another of Sofia's names, Triaditsa (Τριάδιτζα), was mentioned in Greek medieval sources. The Bulgarian name Sredets (СРѢДЄЦЪ), which is related to среда sreda (middle), first appeared in the 11th-century Vision of Daniel and was widely used in the Middle Ages.

The current name Sofia was first used in the 14th-century Vitosha Charter of Bulgarian tsar Ivan Shishman or in a Ragusan merchant's notes of 1376; it refers to the famous Holy Sophia Church, an ancient church in the city named after the Christian concept of the Holy Wisdom. Although Sredets remained in use until the late 18th century, Sofia gradually overcame the Slavic name in popularity.[10] During the Ottoman rule it was called Sofya by the Turkish conquerors of Bulgaria.

The city's name is pronounced by Bulgarians with a stress on the 'o', in contrast with the tendency of foreigners to place the stress on 'i'. The female given name "Sofia" is pronounced by Bulgarians with a stress on the 'i'.

Geography

Sofia's development as a significant settlement owes much to its central position in the Balkans. It is situated in western Bulgaria, at the northern foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the Sofia Valley that is surrounded by mountains on all sides. The valley has an average altitude of 550 metres (1,800 ft). Three mountain passes lead to the city, which have been key roads since antiquity, connecting the Adriatic Sea and Central Europe with the Black and Aegean Seas. A number of low rivers cross the city, including the Vladaiska and the Perlovska. The Iskar River in its upper course flows near eastern Sofia. The city is known for its 49 mineral and thermal springs. Artificial and dam lakes were built in the twentieth century.

It is 130 kilometres (81 mi) northwest of Plovdiv,[11] Bulgaria's second largest city, 340 kilometres (210 mi) west of Burgas[11] and 380 kilometres (240 mi) west of Varna,[11] Bulgaria's major port-cities on the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast. The city is less than 200 kilometres (120 mi) from the borders with three countries: 55 kilometres (34 mi) from Kalotina on the Serbian border, 113 kilometres (70 mi) from Gyueshevo on the frontier with the Republic of Macedonia and 183 kilometres (114 mi) from the Greek border at Kulata.

Sofia has an area of 1344 km2.[12]

Climate

Sofia has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb) with an average annual temperature of 11.4 °C (52.5 °F).

Winters are cold and snowy. In the coldest days temperatures can drop as low as −15 °C (5 °F) or even lower, most notably in January. Foggy conditions are frequent, especially in the beginning of the season. On average, Sofia receives a total snowfall of 93 cm (36.6 in) and 60 days with snow cover.

Summers are warm and sunny. In summer, the city generally remains slightly cooler than other parts of Bulgaria, due to its higher altitude. However, the city is also subjected to heat waves with high temperatures reaching or exceeding 35 °C (95 °F) in the hottest days, particularly in July and August.

Springs and autumns in Sofia are short with variable and dynamic weather.

The city receives an average precipitation of 587 mm (23.11 in) a year, reaching its peak in late spring and early summer when thunderstorms are common.

| Climate data for Sofia, Bulgaria | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19 (66) |

22 (72) |

31 (88) |

31 (88) |

34 (93) |

38 (100) |

41 (106) |

39.4 (102.9) |

36.1 (97) |

33.9 (93) |

25.5 (77.9) |

23 (73) |

41 (106) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.0 (39.2) |

5.8 (42.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.9 (71.4) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

11.1 (52) |

4.5 (40.1) |

16.6 (61.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.5 (32.9) |

1.5 (34.7) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

17.2 (63) |

12.2 (54) |

6.7 (44.1) |

0.8 (33.4) |

11.4 (52.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.6 (25.5) |

−2.2 (28) |

1.5 (34.7) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

13.3 (55.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

6.7 (44.1) |

2.2 (36) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

6.1 (43) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.5 (−17.5) |

−25 (−13) |

−16.1 (3) |

−6 (21) |

−2.2 (28) |

5.4 (41.7) |

7.5 (45.5) |

8.1 (46.6) |

−2 (28) |

−6 (21) |

−15.3 (4.5) |

−20.7 (−5.3) |

−27.5 (−17.5) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 31 (1.22) |

32.3 (1.272) |

37.4 (1.472) |

50.5 (1.988) |

74.4 (2.929) |

73.9 (2.909) |

61.3 (2.413) |

53.6 (2.11) |

45 (1.77) |

42.2 (1.661) |

43.5 (1.713) |

42 (1.65) |

587 (23.11) |

| Avg. precipitation days | 9 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 125 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 89.9 | 123.2 | 179.8 | 192.0 | 254.2 | 285.0 | 322.4 | 294.5 | 210.0 | 170.5 | 120.0 | 58.9 | 2,300.4 |

| Source #1: Climatebase.ru;[13] ECA&D[14] (precip. and sun), Climatedata.eu[15] (precip. days) | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: NOAA;[16] Freemeteo.com;[17] Stringmeteo.com[18][19] (some extremes) | |||||||||||||

History

Antiquity

Sofia was originally a Thracian settlement called Serdica, or Sardica, possibly named after the Celtic tribe Serdi.[9] For a short period during the 4th century BC, the city was ruled by Philip of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great. Around BC 29, Serdica was conquered by the Romans. It became a municipium, or centre of an administrative region, during the reign of Emperor Trajan (98–117) and was renamed Ulpia Serdica. It seems that the first written mention of Serdica was made by Ptolemy (around 100 AD).

Serdica (Sardica) expanded, as turrets, protective walls, public baths, administrative and cult buildings, a civic basilica, an amphitheatre, the City Council (Boulé), a large forum, a big circus (theatre), etc. were built.

In the 2nd century AD, it was administrative centre of Roman Moesia. In the 3rd century, it was the capital of Dacia Aureliana,[20] and when Emperor Diocletian divided the province of Dacia into Dacia Ripensis (at the banks of the Danube) and Dacia Mediterranea, Serdica became the capital of the latter. The city subsequently expanded for a century and a half, it became a significant political and economical centre, more so — it became one of the first Roman cities where Christianity was recognized as an official religion (under Galerius). In 343 AD, the Council of Sardica was held in the city, in a church located where the current 6th century Church of Saint Sophia was later built.

The city was destroyed in the 447 invasion of the Huns.[21] It was rebuilt by Byzantine Emperor Justinian I and for a while called Triaditsa or Sredets by the Slavonic tribes. During the reign of Justinian it flourished, being surrounded with great fortress walls whose remnants can still be seen today.

Middle Ages and Ottoman rule

Sofia first became part of the First Bulgarian Empire during the reign of Khan Krum in 809, after a long siege.[22] Afterwards, it was known by the Bulgarian name "Sredets" and grew into an important fortress and administrative centre. After the fall of North-eastern Bulgaria under John I Tzimiskes' armies in 971, the Bulgarian Patriarch Damyan chose Sofia for his seat in the next year. After a number of unsuccessful sieges, the city fell to the Byzantine Empire in 1018, but once again was incorporated into the restored Bulgarian Empire at the time of Tsar Ivan Asen I.

From the 12th to the 14th century, Sofia was a thriving centre of trade and crafts. It is possible that it had been called by the common population Sofia (meaning "wisdom" in Ancient Greek) about 1376 after the church of Saint Sophia. However, in different testimonies it was called both "Sofia" and "Sredets" until the end of the 19th century. In 1382, Sofia was seized by the Ottoman Empire in the course of the Bulgarian-Ottoman Wars after a long siege. Around 1393 it became the seat of newly established Sanjak of Sofia.[23]

After the failed crusade of Władysław III of Poland in 1443 towards Sofia, the city's Christian elite was annihilated and the city became the capital of the Ottoman province (beylerbeylik) of Rumelia for more than four centuries, which encouraged many Turks to settle there. In the 16th century, Sofia's urban layout and appearance began to exhibit a clear Ottoman style, with many mosques, fountains and hamams (bathhouses). During that time the town had a population of around 7,000.

The town was seized for several weeks by Bulgarian hayduts in 1599. In 1610 the Vatican established the See of Sofia for Catholics of Rumelia, which existed until 1715 when most Catholics had emigrated.[24] In the 16th century there were 126 Jewish households, and there has been a synagogue in Sofia since 967. The town was the center of Sofya Eyalet (1826–1864).

Modern and contemporary history

Sofia was taken by Russian forces on January 4, 1878, during the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–78, and became the capital of the autonomous Principality of Bulgaria in 1879, which became the Kingdom of Bulgaria in 1908. It was proposed as a capital by Marin Drinov and was accepted as such on 3 April 1879. After the Liberation War, the new name "Sofia" replaced the old one ("Sredets"). By the time of its liberation the population of the city was 11,649.[25] For a few decades after the liberation the city experienced large population growth mainly from other regions of the country.

During World War II, Sofia was bombed by Allied aircraft in late 1943 and early 1944. As a consequence of the invasion of the Soviet Red Army, Bulgaria's government, which was allied with Germany, was overthrown.

The transformations of Bulgaria into a People's Republic in 1946 and Republic of Bulgaria marked significant changes in the city's appearance. The population of Sofia expanded rapidly due to migration from the country. Whole new residential areas were built in the outskirts of the city, like Druzhba, Mladost and Lyulin.

Cityscape

Districts

Politically, administratively and economically, Bulgaria is a highly centralized state, making Sofia a national administrative unit of its own right. It should not to be confused with Sofia Province, which surrounds but does not include the city itself. Besides the city proper, the 24 districts of Sofia encompass three other towns and 34 villages.[26] Each of them has its own district mayor who is elected in a popular election.[26] The head of the Sofia Municipality is its mayor. The assembly members are chosen every four years. The current mayor of Sofia is Yordanka Fandakova.

The following are some of the most culturally and economically significant districts:

- Oborishte (Bulgarian: Оборище) is in the very center of the city, where most landmarks and administrative edifices are located. It is known for its predominantly neo-Renaissance and Viennese architecture, extensive green belts and yellow cobblestones.

- Sredets (Bulgarian: Средец) neighbours Oborishte and shares some of its specific architecture. It is the site of Borisova gradina (Gardens of Boris) and the Vasil Levski National Stadium.

- Vazrazhdane (Bulgarian: Възраждане) is an economically active district where many trade centres and banks, along with some light industry manufacturing companies, are located. One of its main boulevards is Marie Louise Boulevard, the site of the Central Sofia Market Hall, TZUM and St Nedelya Church.

- Mladost (Bulgarian: Младост) is one of the most modern and fast developing areas in Sofia. It's also one of the largest districts in terms of population (second only to Lyulin) with its 110,000 inhabitants. It is generally poor in landmarks and administrative institutions, but it concentrates the headquarters of numerous domestic and international companies, large-scale department stores, official vehicle dealerships, and Business Park Sofia at its southern end. The architecture is a combination of Socialist-era apartment blocks, industrial enterprises and new buildings, most of which were constructed after 2004. Mladost has excellent transport connections to all remaining districts of Sofia.

- Vitosha (Bulgarian: Витоша) is located on the foot of Vitosha Mountain. It holds a key location as it is the site where the Sofia ring road and Bulgaria Boulevard cross. Luxury estates and villa complexes dominate in Vitosha district. It has good connections to both the city centre and the nearby mountain resorts. Boyana is the site of the presidential residence, the Nu Boyana Film studios, the National Historical Museum and the Boyana Church.

Architecture

The outlook of Sofia combines a wide range of architectural styles, some of which are hardly compatible. These vary from Christian Roman architecture and medieval Bulgar fortresses to Neoclassicism and prefabricated Socialist-era apartment blocks (panelki). A number of ancient Roman, Byzantine and medieval Bulgarian buildings are preserved in the centre of the city. These include the 4th century Rotunda of St. George, the walls of the Serdica fortress and the partially preserved Amphitheatre of Serdica.

| Architectural styles in Sofia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

After the Liberation War, knyaz Alexander Battenberg invited architects from Austria–Hungary to shape the new capital's architectural appearance.[27] Among the architects invited to work in Bulgaria were Friedrich Grünanger, Adolf Václav Kolář, Viktor Rumpelmayer and others, who designed the most important public buildings needed by the newly reestablished Bulgarian government, as well as numerous houses for the country's elite.[27] Later, many foreign-educated Bulgarian architects also contributed. The architecture of Sofia's centre is thus a combination of Neo-Baroque, Neo-Rococo, Neo-Renaissance and Neoclassicism, with the Vienna Secession also later playing an important part, but it is mostly typically Central European.

After the Second World War and the establishment of a Communist government in Bulgaria in 1944, the architectural line was substantially altered. Stalinist Gothic public buildings emerged in the centre, notably the spacious government complex around The Largo, Vasil Levski Stadium, the Cyril and Methodius National Library and others. As the city grew outwards, the then-new neighbourhoods were dominated by many concrete tower blocks, prefabricated panel apartment buildings and examples of Brutalist architecture.

After the abolition of Communism in 1989, Sofia has witnessed the construction of whole business districts and neighbourhoods, as well as modern skryscraper-like glass-fronted office buildings, but also top-class residential neighbourhoods. Capital Fort Business Center will be the first skyscraper in Bulgaria with its 126 m and 36 floors. However, the end of the old administration and centrally planned system also paved the way for chaotic and unrestrained construction, which continues to the present day.

Green areas

The city has an extensive green belt. Some of the neighbourhoods constructed after 2000 which are densely built-up often lack green spaces. There are four principal parks – Borisova gradina in the city centre and the Southern, Western and Northern parks. The Southern Park was under reconstruction and is now one of the best parks in the country. Several other smaller parks, among which the City Garden and the Doctors' Garden, are located in central Sofia. The Vitosha Nature Park (the oldest national park in the Balkans), [28] which includes a large portion of Vitosha mountain, covers an area of almost 270 square kilometres (104 sq mi) and lies entirely within the city limits.[29] Many of the city's residents take weekly hikes up the mountain, and most do so at least a couple of times a year. There are bungalows as well as several ski slopes on Vitosha, allowing locals to take full advantage of the countryside and of the mountains without having to leave the city.

Culture

Arts and entertainment

Sofia concentrates the majority of Bulgaria's leading performing arts troupes. Theatre is by far the most popular form of performing art, and theatrical venues are among the most visited, second only to cinemas. The oldest such institution is the Ivan Vazov National Theatre, which performs mainly classical plays and is situated in the very centre of the city. A large number of smaller theatres, such as the Sfumato Theatrical Workshop, show both classical and modern plays.

The National Opera and Ballet is a combined opera and ballet collective, established in 1891. However, it did not begin performances on a regular basis until 1909. Some of Bulgaria's most famous operatic singers, such as Nicolai Ghiaurov and Ghena Dimitrova, have made their first appearances on the stage of the National Opera and Ballet. Bulgaria Hall and Hall 1 of the National Palace of Culture regularly hold classical concerts, performed both by foreign orchestras and the Sofia Philharmonic. The city has played host to many world-famous musical acts including AC/DC, Sting, Elton John, Madonna, George Michael, Metallica, Tiesto, Kylie Minogue, Depeche Mode, Rammstein, Rihanna, Roxette and Lady Gaga.

Bulgaria's largest art museums are located in the central areas of the city. The National Art Gallery holds a collection of works mostly by Bulgarian authors, while the National Gallery for Foreign Art displays exclusively foreign art, mostly from India, Africa, China and Europe. Its collections encompass diverse cultural items such as Ashanti Empire sculptures, Buddhist art, Dutch Golden Age painting, works by Albrecht Dürer, Jean-Baptiste Greuze and Auguste Rodin, among others. The crypt of the Alexander Nevsky cathedral holds a collection of Eastern Orthodox icons from the 9th to the 19th century. Other museums are the National Historical Museum with a collection of more than 600,000 items; the National Polytechnical Museum with more than 1,000 technological items on display; the National Archaeological Museum and the Museum of Natural History.

Cinema is the most popular form of entertainment. In recent years, cinematic venues have been concentrating in trade centres and malls, and independent halls have been closed. Mall of Sofia holds one of the largest IMAX cinemas in Europe. Most films are American productions, although European and domestic films are increasingly shown. Odeon (not part of the Odeon Cinemas chain) shows exclusively European and independent American films, as well as 20th century classics. Bulgaria's once thriving film industry, concentrated in the Boyana Film studios, has suffered a period of decay after 1990. A relative revival of the industry began after 2001. After the acquisition of Boyana Film by Nu Image, several moderately successful productions have been shot in and around Sofia, such as The Contract, The Black Dahlia, Hitman and Conan the Barbarian. The Nu Boyana Film studios have also hosted some of the scenes for The Expendables 2.

The city houses many cultural institutes such as the Russian Cultural Institute, the Polish Cultural Institute, the Hungarian Institute, the Czech and the Slovak Cultural Institutes, the Italian Cultural Institute, the French Cultural Institute, Goethe Institut, British Council, Instituto Cervantes, and the Open Society Institute, which regularly organise temporary expositions of visual, sound and literary works by artists from their respective countries.

Some of the biggest telecommunications companies, TV and radio stations, newspapers, magazines, and web portals are based in Sofia, including the Bulgarian National Television, bTV and Nova TV. Top-circulation newspapers include 24 Chasa, Trud and Kapital Daily.

Tourism

Sofia is one of the most visited tourist destinations in Bulgaria alongside coastal and mountain resorts. Among its highlights is the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, one of the symbols of Bulgaria, constructed in the late 19th century. It occupies an area of 3,170 square metres (34,100 sq ft) and can hold 10,000 people. The city is also known for the Boyana Church, a UNESCO World Heritage site. The SS. Cyril and Methodius National Library houses the largest national collection of books and documents (1,714,211 books and some 6 million other documents)[30] and is Bulgaria's oldest cultural institute.

Sofia holds Bulgaria's largest museum collections, which attract tourists and students for practical studies. The National Historical Museum in Boyana district has a vast collection of more than 650,000 historical items dating from Prehistory to the modern era, although only 10,000 of them are permanently displayed due to the lack of space.[31] Smaller collections of items related mostly to the history of Sofia are in the National Archaeological Museum, a former mosque located between the edifices of the National Bank and the Presidency. Two natural sciences museums — the Natural History Museum and the Earth and Man — display minerals, animal species (alive and taxidermic) and rare materials. The Ethnographic Museum and the National Museum of Military History are other places of interest, holding large collections of Bulgarian folk costumes and armaments, respectively.

Vitosha Boulevard, also called Vitoshka, has numerous fashion boutiques and luxury goods stores. Sofia's geographic location, in the foothills of the weekend retreat Vitosha mountain, further adds to the city's specific atmosphere.

Sports

A large number of sports clubs are based in the city. During the Communist era most sports clubs concentrated on all-round sporting development, therefore CSKA, Levski and Slavia are dominant not only in football, but in many other team sports as well. Basketball and volleyball also have strong traditions in Sofia. A notable local basketball team is twice European Champions Cup finalist Lukoil Akademik. The Bulgarian Volleyball Federation is the world's second-oldest, and it was an exhibition tournament organised by the BVF in Sofia that convinced the International Olympic Committee to include volleyball as an olympic sport in 1957.[32] Tennis is increasingly popular in the city. Currently there are some ten[33] tennis court complexes within the city including the one founded by former WTA top-ten athlete Magdalena Maleeva.[34]

Sofia applied to host the Winter Olympic Games in 1992 and in 1994, coming 2nd and 3rd respectively. The city was also an applicant for the 2014 Winter Olympics, but was not selected as candidate. In addition, Sofia hosted Eurobasket 1957 and the 1961 and 1977 Summer Universiades, as well as the 1983 and 1989 winter editions. In 2012, it hosted the FIVB World League finals.

The city is home to a number of large sports venues, including the 43,000-seat Vasil Levski National Stadium which hosts international football matches, and Lokomotiv Stadium, the main venue for outdoor musical concerts. Armeets Arena holds many indoor events and has a capacity of up to 19,000 people depending on its use. The venue was inaugurated on July 30, 2011, and the first event it hosted was a friendly volleyball match between Bulgaria and Serbia. There are two ice skating complexes — the Winter Palace of Sports with a capacity of 4,000 and the Slavia Winter Stadium with a capacity of 2,000, both containing two rinks each.[35] A velodrome with 5,000 seats in the city's central park is currently undergoing renovation.[36] There are also various other sports complexes in the city which belong to institutions other than football clubs, such as those of the National Sports Academy, the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, or those of different universities. There are more than fifteen swimming complexes in the city, most of them outdoor.[37] Nearly all of these were constructed as competition venues and therefore have seating facilities for several hundred people.

There are two golf courses just to the east of Sofia — in Elin Pelin (St Sofia club) and in Ihtiman (Air Sofia club), and a horseriding club (St George club).

Sofia was set to bid for the 2016 Winter Youth Olympics but didn't submit a bid citing they filled the requirements set by the IOC. The Bulgarian Olympic Committee have expressed interest in potentially bidding for the 2020 Winter Youth Olympics[38]

Demographics

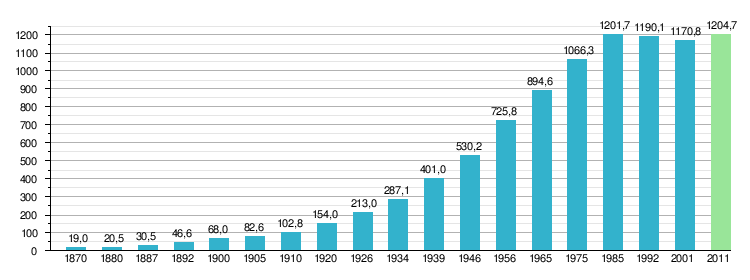

According to 2012 data,[3] the city has a population of 1,241,396 and the whole Capital Municipality of 1,301,683.[4]

The ratio of women per 1,000 men was 1,102. The birth rate per 1000 people was 12.3 per mille and steadily increasing in the last 5 years, the death rate reaching 12.1 per mille and decreasing. The natural growth rate during 2009 was 0.2 per mille, the first positive growth rate in nearly 20 years. The considerable immigration to the capital from poorer regions of the country, as well as urbanisation, are among the other reasons for the increase in Sofia's population. 4.8 people of every one thousand were wedded in 2009 (only heterosexual marriage is possible in Bulgaria) and the infant mortality rate was 5.6 per 1,000, down from 18.9 in 1980.

According to the 2011 census, Sofia's population was made up of 96.4% ethnic Bulgarians; among minority communities, about 18,300 (1.6%) officially identified themselves as Roma,[39] 6,500 (0.6%) as Turkish and 1.4% belonged to other ethnic groups or did not self-declare.

The unemployment is lower than in other parts of the country — 2.45% of the active population in 1999 and declining, compared to 7.25% for the whole of Bulgaria as of 1 July 2007.[40] The large share of unemployed people with higher education, 27% as compared to 7% for the whole country, is a characteristic feature of the capital.

Sofia was declared the national capital in 1879. One year later, in 1880, it was the fifth-largest city in the country after Plovdiv, Varna, Ruse and Shumen. Plovdiv remained the most populous Bulgarian town until 1892 when Sofia took the lead.

Economy

Sofia is the economic heart of Bulgaria and home to most major Bulgarian and international companies operating in the country, as well as the Bulgarian National Bank and the Bulgarian Stock Exchange. The city and its surrounding Yugozapaden NUTS II planning region have a PPS GDP of €18,400,[41] which makes it the most developed region in the country. In 2008, the average per capita annual income was 4,572 leva ($3,479).[42] For the same year, the strongest sectors of the city's economy in terms of annual production were manufacturing ($5.5 bln.), metallurgy ($1.84 bln.), electricity, gas and water supply ($1.6 bln.) and food and beverages ($778 mln.).[43] Economic output in 2011 amounted to 15.9 billion leva, or $11.04 billion.[44]

After World War II and the era of industrialisation under socialism, the city and its surrounding areas expanded rapidly and became the most heavily industrialised region of the country.[45] The influx of workers from other parts of the country became so intense that a restriction policy was imposed, and residing in the capital was only possible after obtaining Sofianite citizenship.[45] However, after the political changes in 1989, this kind of citizenship was removed.

Increasingly, Sofia is becoming an outsourcing destination for multinational companies, among them IBM, Hewlett-Packard, SAP, Siemens, Software AG.[46] Bulgaria Air, PPD, the national airline of Bulgaria, has its head office on the grounds of Sofia Airport.[47] From 2007 to 2011, the city attracted a cumulative total of $11,6 billion in foreign direct investment.[44]

Up until 2007 Sofia experienced rapid economic growth. In 2008, apartment prices increased dramatically, with a growth rate of 30%.[48] In 2009, prices fell by 26%.[49]

Transport and infrastructure

With its developing infrastructure and strategic location, Sofia is a major hub for international railway and automobile transport. Three of the ten Pan-European Transport Corridors cross the city: IV, VIII and X.[50] All major types of transport (except water) are represented in the city. The Central Railway Station is the primary hub for domestic and international rail transport. Sofia has 186 kilometres of railway lines.[44] Sofia Airport handled some 3.47 million passengers in 2011. [51]

Public transport is well-developed with bus (2,380 km (1,479 mi) network),[52] tram (308 km (191 mi)) network,[53] and trolleybus (193 km (120 mi) network),[54] lines running in all areas of the city,[55] [56] although some of the vehicles are in a poor condition. The Sofia Metro became operational in 1998, and now has two lines and 27 stations.[57] As of 2012, the system has 31 km (19 mi) of track. Six new stations were opened in 2009, two more in April 2012, and eleven more in August 2012. Construction works on the extension of the first line are underway and it is expected to reach the airport by 2014. A third line is currently in the late stages of planning and it is expected that its construction starts in 2014. This line will complete the proposed subway system of three lines with about 65 km (40 mi) of lines. [58] The master plan for the Sofia Metro includes three lines with a total of 63 stations.[59] In recent years the marshrutka, a private passenger van, began serving fixed routes and proved an efficient and popular means of transport by being faster than public transport but cheaper than taxis. As of 2005 these vans numbered 368 and serviced 48 lines around the city and suburbs.[50] There are around 13,000 taxi cabs operating in the city. [60] Low fares in comparison with other European countries, make taxis affordable and popular among a big part of the city population.

Private automobile ownership has grown rapidly in the 1990s; more than 1,000,000 cars were registered in Sofia after 2002. The city has the 4th-highest number of automobiles per capita in the European Union at 546.4 vehicles per 1,000 people.[61] The municipality was known for minor and cosmetic repairs and many streets are in a poor condition. This is noticeably changing in the past years. There are different boulevards and streets in the city with a higher amount of traffic than others. These include Tsarigradsko shose, Cherni Vrah, Bulgaria, Slivnitsa and Todor Aleksandrov boulevards, as well as the city's ring road, where long chains of cars are formed at peak hours and traffic jams occur regularly.[62] Consequently traffic and air pollution problems have become more severe and receive regular criticism in local media. The extension of the underground system is hoped to alleviate the city's immense traffic problems.

Sofia has an extensive district heating system based around four combined heat and power (CHP) plants and boiler stations. Virtually the entire city (900,000 households and 5,900 companies) is centrally heated, using residual heat from electricity generation (3,000 MW) and gas- and oil-fired heating furnaces; total heat capacity is 4,640 MW. The heat distribution piping network is 900 km (559 mi) long and comprises 14,000 substations and 10,000 heated buildings.

Education

Sofia concentrates a significant portion of the national higher education capacity, including 109,000 university and college students[63] and 22 of Bulgaria's 51 higher education establishments.[64] These include four of the five highest-ranking national universities - Sofia University (SU), New Bulgarian University, the Technical University of Sofia and the University of Mining and Geology.[65] Sofia University was founded in 1888.[66] More than 20,000 students[67] study in its 16 faculties.[68] A number of research and cultural departments operate within SU, including its own publishing house, botanical gardens,[69] a space research centre, a quantum electronics department,[70] and a Confucius Institute[71] Rakovski Defence and Staff College, the National Academy of Arts, and Sofia Medical University are other major higher education establishments in the city.[65]

Secondary education institutions are numerous and include vocational and language schools. The "elite" secondary language schools provide education in a selected foreign language. These include the First English Language School, Sofia High School of Mathematics, 91st German Language School, 164th Spanish Language School, and 9th French Language School. Some of them provide a language certificate upon graduation, while the 9th French Language School has exchange programs with a number of lycées in France and Switzerland, such as the Parisian Collège-lycée Jacques-Decour. The American College of Sofia, a private secondary school which developed from a school founded by American missionaries in 1860, is among the oldest American educational institutions outside of the US.[72]

Other institutions of national significance, such as the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (BAS) and the SS. Cyril and Methodius National Library are located in Sofia. BAS is the centrepiece of scientific research in Bulgaria, employing more than 4,500 scientists in various institutes, including the Bulgarian Space Agency.

Notable residents

Notable people born in Sofia:

- Galerius (ca. 260-311), Roman emperor[73]

- Georgi Asparuhov (1943–1971), football player

- Michael Bar-Zohar (b. 1938), historian, former Knesset member

- Irina Bokova (b. 1952), politician, director-general of UNESCO

- Boris III (1894–1943), Tsar of Bulgaria

- Albena Denkova (b. 1974), ice dancer, World champion

- Nina Dobrev, (b. 1989), actress

- Kristalina Georgieva (b. 1953), politician, European Commissioner in the second college of the Barroso Commission

- Maria Gigova (b. 1947), three-fold rhythmic gymnastics World champion

- Moshe Gueron (b. 1926), cardiology pioneer

- Assen Jordanoff (1896–1967), aviation pioneer

- Matey Kaziyski (b. 1984), volleyball player

- Ivet Lalova (b. 1983), athlete

- Shmuel Levi (1884–1966), Israeli painter

- Borislav Mikhailov (b. 1963), football player and Bulgarian Football Union president, UEFA executive committee member

- Moni Moshonov (b. 1951), Israeli actor, comedian and theater director

- Valeri Petrov (b. 1920), writer

- Evgenia Radanova (b. 1977), ice skater

- Anna-Maria Ravnopolska-Dean (b. 1960), harpist

- Simeon II (b. 1937), former Tsar of Bulgaria and former Prime Minister of Bulgaria

- Ivo Siromahov (b. 1971), writer, humorist, journalist

- Antoaneta Stefanova (b. 1979), chess player and Women's World Chess Champion

- Tzvetan Todorov (b. 1939), philosopher and writer

- Alexis Weissenberg (1929–2012), pianist

- Lyudmila Zhivkova (1942–1981), art historian and politician

- Eduard Zahariev (1938-1996), film director and screenwriter

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Sofia is twinned with:

Cooperation agreements

In addition Sofia has cooperation agreements with:

Honour

Serdica Peak on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica is named after Serdica.

See also

References

- ↑ "Sofia through centuries". Sofia Municipality. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ↑ Veyrenc, Charles Jacques (1981). Bulgaria. McGraw-Hill/Contemporary. p. 79. "...Here, probably about the 5th century B.C., the Serdi tribe founded the city of Serdica."

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Census of population and households in the Republic of Bulgaria in 2012". Nsi.bg. pp. 15, 16. Retrieved 2012-02-26.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 All municipalities in the District of Sofia City at citypopulation.de

- ↑ Rogers, Clifford (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology 1. Oxford University Press. p. 301. ISBN 9780195334036.

- ↑ "Население по етническа група и майчин език" (in Bulgarian). National Statistical Institute. 13 March 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ↑ Sofia, The Times. Retrieved March 23, 2011

- ↑ Internet Hostel Sofia, Tourism in Sofia. Retrieved Jan, 2012

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "The Cambridge Ancient History", Volume 3, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC by John Boardman, I. E. S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N. G. L. Hammond, ISBN 0-521-22717-8, 1992, p. 600: "In the place of the vanished Treres and Tilataei we find the Serdi for whom there is no evidence before the first century BC. It has for long being supposed on convincing linguistic and archeological grounds that this tribe was of Celtic origin"

- ↑ Чолева-Димитрова, Анна М. (2002). Селищни имена от Югозападна България: Изследване. Речник (in Bulgarian). София: Пенсофт. pp. 169–170. ISBN 954-642-168-5. OCLC 57603720.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Distances between cities in Bulgaria, City of Sofia". Guide Bulgaria. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ "District Sofia-city". Guide Bulgaria. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ↑ Climatebase.ru - Sofia Observ, Bulgaria

- ↑ http://www.stringmeteo.com/synop/semi_cent2.php?year=2012&month=12&stat=2064&sty=1960&endy=2012&prm_in=on&ssh_in=on&mode=stat&submit=%D0%9F%D0%9E%D0%9A%D0%90%D0%96%D0%98

- ↑ http://www.climatedata.eu/climate.php?loc=buxx0005&lang=en

- ↑ ftp://dossier.ogp.noaa.gov/GCOS/WMO-Normals/RA-VI/BU/15614.TXT

- ↑ Weather Forecast Sofia: Weather History: Daily archive

- ↑ http://www.stringmeteo.com/synop/climate_bg/Absolute_Maximum_Temperatures.doc

- ↑ http://www.stringmeteo.com/synop/climate_bg/Absolute_Minimum_Temperatures.doc

- ↑ Wilkes, John (2005). "Provinces and Frontiers". In Bowman, Alan K.; Garnsey, Peter; Cameron, Averil. The Cambridge ancient history: The crisis of empire, A.D. 193-337. The Cambridge ancient history 12. Cambridge University Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-521-30199-2.

- ↑ A New Classical Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography, Mythology and ... - Sir William Smith, Charles Anthon - Google Книги

- ↑ Theophanes Confessor. Chronographia, p.485

- ↑ Godisnjak. Drustvo Istoricara Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo. 1950. p. 174. "Санџак Софија Овај је санџак основан око г. 1393."

- ↑

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Sardica". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Sardica". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ (Bulgarian) Кираджиев, Светлин (2006). „София. 125 години столица. 1879–2004 година“. ИК „Гутенберг“. ISBN 978-954-617-011-8

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "District Mayors". Sofia Municipality. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Collective (1980). Encyclopedia of Figurative Arts in Bulgaria, volume 1. Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. pp. 209–210.

- ↑ "National parks in the world". journey.bg. Retrieved 2008-05-24. (Bulgarian)

- ↑ "Vitosha Mountain". www.vitoshamount.hit.bg. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ↑ Фондове и колекции, Cyrl and Methodius National Library (in Bulgarian)

- ↑ Колекции, National Historical Museum (in Bulgarian)

- ↑ "BVA-News". www.balkanvolleyball.org. Archived from the original on 2008-02-20. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ↑ "Sofia municipality — Tennis courts". www.sofia.bg. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ↑ "Тенис Клуб Малееви". www.maleevaclub.com. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ↑ "Skate rinks in Sofia". kunki.org. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ↑ "Journey.bg — History of the Sofia velodrome". journey.bg. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ↑ "Swimming pools in Sofia (including Spa centers)". tonus.tialoto.bg. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_Winter_Youth_Olympics#Bra.C8.99ov.2C_Romania

- ↑ This statistic should not necessarily be taken at face value due to conflicting data – such as for the predominanly Roma neighbourhood of Fakulteta, which alone has a population of 45,000. Ромите са изолирани от бума в заетостта на Балканите, mediapool.bg, 11 December 2007 (Bulgarian)

- ↑ "Най-ниската безработица от 16 години насам е отчетена през юли" (in Bulgarian). Aktualno.com. 2006-08-14. Retrieved 2006-10-15.

- ↑ "Regional gross domestic product (PPS per inhabitant), by NUTS 2 regions". Eurostat. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ↑ "Sofia in Figures 2009, p.53. Retrieved on 20 March 2012.

- ↑ Sofia in Figures, p.106

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 "Sofia (capital)". National Statistical Institute regional statistics. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 The capital's changing face, The Sofia Echo

- ↑ Invest in Sofia

- ↑ "Contacts." Bulgaria Air. Retrieved on 10 May 2010.

- ↑ "Bulgaria Housing Market Favors Buyers but Far Away from Collapse". www.novinite.com. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ↑ "Bulgaria Residential Property Prices Down by 26% in Q4 y/y". www.novinite.com. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Sofia infrastructure from the official website of the Municipality (Bulgarian)

- ↑ "Sofia Airport — News". www.sofia-airport.bg. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ↑ "History of the bus network in Sofia". Sofiatraffic.bg. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ↑ "History of the tramway network in Sofia". Sofiatraffic.bg. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ↑ "History of the trolleybus network in Sofia". Sofiatraffic.bg. 1941-02-14. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ↑ "Public transport Sofia — official website". www.sumc.bg. Retrieved 2008-05-24. (Bulgarian)

- ↑ "Transport Company Bulgaria— official website". www.dak-transport.com. Retrieved 2009-08-21. (Bulgarian)

- ↑ "Българска национална телевизия - Новини (Bulgarian National Television - News)" (in Bulgarian). www.bnt.bg. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ↑ "Metropolitan Sofia Web Place". www.metropolitan.bg. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ "General Scheme". Metropolitan.bg. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "National Federation of the Taxi Drivers in Bulgaria. Regional Member Sofia". nftvb.com. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ Sofia in Figures, p.26

- ↑ "Fines for bad repair work – 'Dnevnik' newspaper". www.dnevnik.bg. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ http://www.nsi.bg/spageen.php?SHP=66

- ↑ "Accredited Higher Schools in Bulgaria". Ministry of Education, Youth and Science. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 "Bulgarian universities". Webometrics Ranking of World Universities. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ "Official website of the Sofia university — History". Sofia University. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ "Sofia University aims to attract more foreign students" (in Bulgarian). Akademika. 14 June 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ "University Faculties". Sofia University. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ "Independent structures of SU". Sofia University. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ "Faculty of Physics structure". Sofia University. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ "University Centres". Sofia University. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ American College of Sofia Website - History

- ↑ Eutropius. Breviarivm historiae romanae, IX, 22

- ↑ "Kardeş Kentleri Listesi ve 5 Mayıs Avrupa Günü Kutlaması [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Turkish). Ankara Büyükşehir Belediyesi - Tüm Hakları Saklıdır. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ↑ "Twinning Cities: International Relations" (PDF). Municipality of Tirana. www.tirana.gov.al. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ↑ "Twinning Cities: International Relations. Municipality of Tirana". Tirana.gov.al. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Yerevan - Partner Cities". Yerevan Municipality Official Website. © 2005—2013 www.yerevan.am. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- ↑ "Friendship and cooperation agreements". Paris.fr. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ "Acordos de Geminação, de Cooperação e/ou Amizade da Cidade de Lisboa" [Lisbon - Twinning Agreements, Cooperation and Friendship]. Camara Municipal de Lisboa (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2013-08-23.

Further reading

- Gigova, Irina. "The City and the Nation: Sofia’s Trajectory from Glory to Rubble in WWII," Journal of Urban History, March 2011, Vol. 37 Issue 2, pp 155–175; the 110 footnotes provide a guide to the literature on the city

- Sofia in Figures 2009, annual report of the National Statistical Institute

In Bulgarian

- "Sofia — 130 Years Capital" (in Bulgarian).

External links

| Find more about Sofia at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| |

Definitions and translations from Wiktionary |

| |

Media from Commons |

| |

Quotations from Wikiquote |

| |

Source texts from Wikisource |

| |

Textbooks from Wikibooks |

| |

Travel guide from Wikivoyage |

| |

Learning resources from Wikiversity |

- Official website

- Online guide to Sofia

- Official Site of Sofia Public Transport

- Sofia on the Open Directory Project

- Archival images of Sofia

- Virtual Guide to Ancient Serdica

- More than 25 live webcams from Sofia

- Pictures from Vitosha mountain

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

.JPG)