Skinning

Skinning, a gerund from the verb to skin, commonly refers to the act of skin removal.

The process is usually done with animals, mainly as a means to prepare the muscle tissues beneath for consumption and/or for use of the fur or tanning of the skin. The skin may also be used as a trophy, sold on the fur market, or used as proof of kill when collecting a bounty (reward) from a government health, agricultural, or game agency, in the case of a declared pest.

Two common methods of skinning are open skinning and case skinning. Typically large animals are open skinned and smaller animals are case skinned.[1]

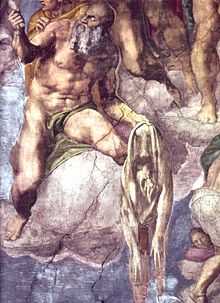

Skinning, when it is performed on live humans as a form of capital punishment, murder, or religious sacrifice, is referred to as flaying.

Skinning Methods

Case skinning is a method where the skin is peeled from the animal like a sock. One would usually use this method if the animal is going to be stretched out or put in dry storage.[2] Many smaller animals are case skinned, leaving the skin mostly undamaged in the shape of a tube.[3]

Although the method of case skinning individual animals varies slightly, the general steps remain the same. To case skin an animal, it should be hung upside down by its feet. A cut should be made in one foot, and continued up the leg, around the anus and down the other leg. From there the skin can be pulled down the animal as though removing a sweater.[4]

Open skinning is a method where the skin is removed from the animal like a jacket. This method is generally used if the skin is going to be tanned immediately or frozen for storage. A skin removed by the open method can be used for wall hangings or rugs.[5] Larger animals are often skinned using the open method.[6]

To open skin an animal, the body should be placed on a flat surface. A cut should be made from anus to lower lip, and up the legs of the animal. The skin can then be opened and removed from the animal.[7]

The final step is to scrape the excess fat and flesh from the inside of the skin with a blunt stone or bone tool.[8]

Dorsal skinning is very similar to process of open skinning, however instead of making a cut up the stomach of the animal, the cut is made along the spine. This method of skinning is very popular among taxidermists, as the backbone is easier and cleaner to access than the stomach and between the legs.[9] The best way to make a dorsal incision is to lay the animal on its abdomen and make a single cut from the base of the tail to the shoulder region. The animal’s skin is easier to remove if it has been freshly killed.[10]

Cape skinning is the process of removing the shoulder, neck and head skin for the purpose of displaying the animal as a trophy on the wall.[11]

Animal Skin and Native Americans

Native Americans used skin for many purposes other than decoration, clothing and blankets. Animal skin was used as a staple to the Native Americans’ daily lives. It was used to make tents and therefore provide shelter, to build boats which provided transportation, to make bags, to create musical instruments such as drums, and even to make quivers which helped them hunt.[12]

Since Native Americans were practiced in the means of acquiring and manipulating animal skin, fur trading developed from contact between them and Europeans in the 16th century. Animal skin was a valuable currency which the Native Americans had in excess and would trade for things such as iron-based tools and tobacco which were common in the more developed European area.[13] Beaver hats became very popular towards the end of the 16th century, and skinning them was necessary to acquire their wool. In this time, the beaver skin drastically rose in demand and in value. However, the high number of beavers being harvested for their pelts led to a depletion of beavers, and the industry had to slow down.[14]

Skinning Controversies

To raise animals for the purpose of collecting their skin is called fur farming. Animal rights organizations such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) bring to light the controversy of skinning animals alive for their fur or skins.[15] Killing tactics deemed brutal by PETA are also in concern. Many fur farms skin animals alive to keep the pelts intact from damage that could occur while killing them. To avoid bullet holes, tears or slits from a knife, fur farmers can use methods such as beating the animal, electrocuting them, using poison to paralyse them, or breaking their necks.[16] Although these methods ensure an undamaged pelt, they are sometimes not enough to confirm the death of the animal, leaving the creature to be skinned alive.

Among many campaigns, one of PETA’s goals is to enforce animal rights so they will not be used in any way as tools for humans. This includes utilizing their skin for clothing or decoration, and especially hurting the animals in any way.[17] Therefore regardless of the method used for animal skinning, PETA is against the industry in general.[18]

See also

- Animal trapping methods: Skinning animals

- Scalping

- Fur farming

Notes

- ↑ Churchill 1983, p.2.

- ↑ Burch 2002, p.63

- ↑ Burch 2002, p.66

- ↑ Churchill 1983, p.44

- ↑ Burch 2002, p.63

- ↑ Churchill 1983, p.44

- ↑ Churchill 1983, p.44

- ↑ Wiens, Ray. "Taxidermy and Field Care Tips and Tricks". Hunting Tips and Tricks. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ↑ Triplett 2006, p.52

- ↑ Triplett 2006, p.53

- ↑ Wiens, Ray. "Taxidermy and Field Care Tips and Tricks". Hunting Tips and Tricks. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ↑ Pritzer, Barry. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. Print.

- ↑ Carlos, Ann M., Frank D. Lewis (February 1, 2011). "The Economic History of the Fur Trade: 1670 to 1870". EH.net encyclopedia. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ↑ Carlos, Ann M., Frank D. Lewis (February 1, 2011). "The Economic History of the Fur Trade: 1670 to 1870". EH.net encyclopedia. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Fur Farms". PETA. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Fur Farms". PETA. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Animals rights". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Uncompromising Stands on Animal Rights". PETA. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

References

Burch, Monte. The Ultimate Guide to Skinning and Tanning: A Complete Guide to Working With Pelts, Furs and Leathers. Guilford: The Lyons Press, 2002. Print.

James E. Churchill. The Complete Book of Tanning Skins and Furs. Mecanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 1983. Print.

Pritzer, Barry. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. Print.

Triplett, Todd. Big-Game Taxidermy: A Complete Guide to Deer, Antelope and Elk. United States of America: The Lyons Press, 2006. Print.