Sino-Roman relations

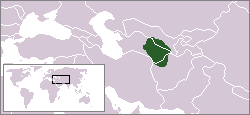

Sino-Roman relations were essentially indirect throughout the existence of both empires. The Roman Empire and Han China progressively inched closer in the course of the Roman expansion into the Ancient Near East and simultaneous Chinese military incursions into Central Asia. However, powerful intermediate empires such as the Parthians and Kushans kept the two Eurasian flanking powers permanently apart and mutual awareness remained low and knowledge fuzzy.

Only a few attempts at direct contact are known from records: In CE 97, the Chinese general Ban Chao unsuccessfully tried to send an envoy to Rome.[1][2] Several alleged Roman emissaries to China were recorded by ancient Chinese historians. The first one on record, supposedly from either the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius or the later emperor Marcus Aurelius, arrived in CE 166.[3][4]

The indirect exchange of goods on the land (the so-called silk road) and sea routes included Chinese silk and Roman glassware and high-quality cloth.[5]

In classical sources, the problem of identifying references to ancient China is exacerbated by the interpretation of the Latin term "Seres," whose meaning fluctuated and could refer to a number of Asian people in a wide arc from India over Central Asia to China.[6] In Chinese records, the Roman Empire came to be known as "Da Qin", Great Qin, apparently thought to be a sort of counter-China at the other end of the world.[7] According to Edwin G. Pulleyblank, the "point that needs to be stressed is that the Chinese conception of Da Qin was confused from the outset with ancient mythological notions about the far west".[4]

Embassies and travels

Embassy to Augustus

The Roman historian Florus describes the visit of numerous envoys, including "Seres" (Chinese, or, more probably Central Asians), to the first Roman Emperor Augustus, who reigned between 27 BCE and CE 14:

Even the rest of the nations of the world which were not subject to the imperial sway were sensible of its grandeur, and looked with reverence to the Roman people, the great conqueror of nations. Thus even Scythians and Sarmatians sent envoys to seek the friendship of Rome. Nay, the Seres came likewise, and the Indians who dwelt beneath the vertical sun, bringing presents of precious stones and pearls and elephants, but thinking all of less moment than the vastness of the journey which they had undertaken, and which they said had occupied four years. In truth it needed but to look at their complexion to see that they were people of another world than ours.[8]

Envoy Gan Ying

In CE 97, a Chinese envoy named Gan Ying, sent by the general Ban Chao, made his way from the Tarim Basin to Parthia and reached the Persian Gulf. Gan Ying left a detailed account of western countries, although he apparently only reached as far as Mesopotamia, then under the control of the Parthian Empire. While he intended to sail to the Roman Empire, he was discouraged when told that the dangerous trip could take up to two years. Deterred, he returned home to China bringing much new information on the countries to the west of Chinese-controlled territories.[9]

Gan Ying is thought to have left an account of the Roman Empire (Daqin in Chinese) which relied on secondary sources — likely sailors in the ports which he visited. The Hou Hanshu locates it in Haixi (lit. "west of the sea" = Egypt, which was then under Roman control. The sea is the one known to the Greeks and Romans as the Erythraean Sea, which included the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, and Red Sea):

Its territory extends for several thousands of li [a li during the Han equaled 415.8 metres],[10] They have established postal relays at intervals, which are all plastered and whitewashed. There are pines and cypresses, as well as trees and plants of all kinds. It has more than four hundred walled towns. There are several tens of smaller dependent kingdoms. The walls of the towns are made of stone.[11]

The Hou Hanshu gives a positive, if somewhat fanciful, view of Roman governance:

Their kings are not permanent. They select and appoint the most worthy man. If there are unexpected calamities in the kingdom, such as frequent extraordinary winds or rains, he is unceremoniously rejected and replaced. The one who has been dismissed quietly accepts his demotion, and is not angry. The people of this country are honest. They resemble the Chinese, and that is why the country is called Da Qin (The "Great" Qin) ... The soil produced lots of gold, silver, and rare jewels, including the jewel which shines at night ... they sew embroidered tissues with gold threads to form tapestries and damask of many colours, and make a gold-painted cloth, and a "cloth washed-in-the-fire" (asbestos).—Hou Hanshu, cited in Leslie and Gardiner

The report described Rome correctly as the main economic power at the western end of Eurasia:

It is from this country that all the various marvellous and rare objects of foreign states come.—Hou Hanshu, cited in Leslie and Gardiner

The author of the Hou Hanshu, Fan Ye (historian), summed up:

In the ninth year [97 CE], Ban Chao sent his Senior Clerk Gan Ying, who probed as far as the Western Sea, and then returned. Former generations never reached these regions. The Shanjing gives no details on them. Undoubtedly he prepared a report on their customs and investigated their precious and unusual [products]. After this, distant kingdoms [such as] Mengqi and Doule [Talas] all came to submit, and sent envoys offering tribute.[12]

Eastern travels of Maes Titianus

Maës Titianus, an ancient Roman traveller,[13] penetrated farthest east along the Silk Road from the Mediterranean world. In the early 2nd century[14] or at the end of the 1st century CE,[15] during a lull in the intermittent Roman struggles with Parthia, his party reached the famous Stone Tower, which, according to one theory, was Tashkurgan,[16] in the Pamirs. According to other writers, the 'Stone Tower' must have been located in the Alai Valley, west of Kashgar.[17][18][19]

First Roman embassy

Direct trade links between the Mediterranean lands and India had been established in the 1st century BCE, after Greek navigators learned to use the regular pattern of the monsoon winds for their trade voyages in the Indian Ocean. The lively sea trade in Roman times is confirmed by the excavation of large deposits of Roman coins along much of the coast of India. Many trading ports with links to Roman communities have been identified in India and Sri Lanka along the route used by the Roman mission.

The first group of people claiming to be an ambassadorial mission of Romans to China was recorded in CE 166 by the Hou Hanshu. The embassy came to Emperor Huan of Han China "from Andun (Chinese: 安敦; Emperor Antoninus Pius), king of Daqin (Rome)". As Antoninus Pius died in 161, leaving the empire to his adoptive son Marcus Aurelius (Antoninus), and the envoy arrived in 166, confusion remains about who sent the mission given that both Emperors were named 'Antoninus'. The Roman mission came from the south (therefore probably by sea), entering China by the frontier of Rinan or Tonkin (present-day Vietnam). It brought presents of rhinoceros horns, ivory, and tortoise shell, probably acquired in Southern Asia.[20] The text specifically states that it was the first time there had been direct contact between the two countries.[3]

While the existence of China was clearly known to Roman cartographers of the time, its geographical position is depicted in Ptolemy's Geographia from c. CE 150 rather vaguely: On the map, China is located beyond the Aurea Chersonesus ("Golden Peninsula"), which refers to the Southeast Asian peninsula. It is shown as being on the Magnus Sinus ("Great Gulf"), which presumably corresponds to the known areas of the China Sea at the time; although Ptolemy represents it as tending to the southeast rather than to the northeast.

Other Roman embassies

The Liangshu records the arrival in CE 226 of a merchant from the Roman Empire (Da Qin) at Jiaozhi (near modern Hanoi). The Prefect of Jiaozhi sent him to Sun Quan [the Wu (kingdom) emperor], who asked him for a report on his native country and its people. An expedition was mounted to return the merchant along with 10 female and 10 male "blackish coloured dwarfs" he had requested as a curiosity and a Chinese officer who, unfortunately, died en route.[21]

An account appears about presents sent in the early 3rd century by the Roman Emperor to Cao Rui of the Kingdom of Wei (reigned 227–239) in Northern China. The presents consisted of articles of glass in a variety of colours. While several Roman Emperors ruled during this time, the embassy, if genuine, may have been sent by Severus Alexander; since his successors reigned briefly and were busy with civil wars.

Another embassy from Daqin is recorded in the year 284, as bringing presents to the Chinese empire. This embassy presumably was sent by the Emperor Carus (282–283), whose short reign was occupied by war with Persia.

Chinese annals record other contacts with merchants from 'Fu-lin,' the new name used to designate the Byzantine Empire, the continuation of the Roman Empire in the east, taking place in 643 during the reign of Constans II (641-668).[22] Other contacts are reported taking place in 667, 701, and perhaps 719, sometimes through Central Asian intermediaries.[23] Still other contacts are recorded by the Chinese in the 11th century.

Trade relations

Roman exports to China

High-quality glass from Roman manufactures in Alexandria and Syria was exported to many parts of Asia, including Han China. Further Roman luxury items which were greatly esteemed by the Chinese were gold-embroidered rugs and gold-coloured cloth, asbestos cloth and sea silk, a cloth made from the silk-like hairs of certain Mediterranean shell-fish, the Pinna nobilis.[24][25]

Asian silk in the Roman Empire

Trade with the Roman Empire, confirmed by the Roman craze for silk, started in the 1st century BCE. Although the Romans knew of wild silk harvested on Cos (coa vestis), they did not at first make the connection with silk which was also produced in the Pamir Sarikol kingdom.[26] There were few direct trade contacts between Romans and Han Chinese, as the rivalling Parthians and Kushans were each jealously protecting their lucrative role as trade intermediaries.[27][28]

Much of what we know from the Roman side of the silk trade, and silk in general, comes from Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History:

The Seres are famous for the woolen substance obtained from their forests; after a soaking in water they comb off the white down of the leaves… So manifold is the labour employed, and so distant is the region of the globe drawn upon, to enable the Roman maiden to flaunt transparent clothing in public.

Pliny the Elder wrote about the large value of the trade between Rome and Eastern countries:[29]

"By the lowest reckoning, India, Seres and the Arabian peninsula take from our Empire 100 millions of sesterces every year: that is how much our luxuries and women cost us."

Yet, later in the same work, he writes:

The larva [of the 'bombyx'] then becomes a caterpillar, after which it assumes the state in which it is known as 'bombylis', then that called 'necydalus', and after that, in six months, it becomes a silk-worm. These insects weave webs similar to those of the spider, the material of which is used for making the more costly and luxurious garments of females, known as 'bombycina'. Pamphile, a woman of Cos, the daughter of Platea, was the first person who discovered the art of unravelling these webs and spinning a tissue therefrom; indeed, she ought not to be deprived of the glory of having discovered the art of making vestments which, while they cover a woman, at the same moment reveal her naked charms.

The Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds: the importation of silk caused a huge outflow of gold, and silk clothes were considered to be decadent and immoral:

I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes ... Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body.

The Roman historian Florus also describes the visit of numerous envoys, including Seres and "Indians" (who may have included Kushans), to the first Roman Emperor Augustus, who reigned between 27 BCE and 14 CE:

Now that all the races of the west and south were subjugated, and also the races of the north, (...) the Scythians and the Sarmatians sent ambassadors seeking friendship; the Seres too and the Indians, who live immediately beneath the sun, though they brought elephants amongst their gifts as well as precious stones and pearls, regarded their long journey, in the accomplishment of which they had spent four years, as the greatest tribute which they rendered, and indeed their complexion proved that they came from beneath another sky.

A maritime route opened up with the Chinese-controlled Jiaozhi (centred in modern Vietnam) and the Khmer kingdom of Funan by the 2nd century, if not earlier.[31] Jiaozhi was proposed by Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877 to have been the port known to the geographer Ptolemy and the Romans as Kattigara or Cattigara, situated near modern Hanoi.[32] Richthofen's view was widely accepted until archaeology at Óc Eo in the Mekong Delta suggested that site may have been its location. At the formerly coastal site of Óc Eo in the Mekong Delta, Roman coins were among the vestiges of long-distance trade discovered by the French archaeologist Louis Malleret in the 1940s.[33] The trade connection extended, via ports on the coasts of India and Sri Lanka, all the way to Roman-controlled ports in Egypt and the Nabataean territories on the northeastern coast of the Red Sea.

Hypothetical military contact

The historian Homer H. Dubs speculated in 1941 that Roman prisoners of war who were transferred to the Parthian eastern border might have later clashed with Han troops there.[34]

After losing at the battle of Carrhae in 54 BCE, an estimated 10,000 Roman prisoners were displaced by the Parthians to Margiana to man the frontier. Some time later the nomadic Xiongnu chief Zhizhi established a state further east in the Talas valley, near modern day Taraz. Taking up these two strands, Dubs points to a Chinese account by Ban Gu of about "a hundred men" under the command of Zhizhi who fought in a so-called "fish-scale formation" to defend Zhizhi's wooden-palisade fortress against Han forces, in the Battle of Zhizhi in 36 BCE. He claimed that this might have been the Roman testudo formation and that these men, who were captured by the Chinese, founded the village of Liqian (Li-chien, possibly from "legion") in Yongchang County.[35]

However, Dubs' synthesis of Roman and Chinese sources has not found acceptance among modern historians on the grounds of being highly speculative and jumping to too many conclusions.[36] Although DNA testing in 2005 confirmed a predominantly "Caucasian origin" of a few inhabitants of Liqian, this influx of Western genes could be explained just as well by transethnic marriages with other peoples along the silk road.[37][38][39] A much more comprehensive DNA analysis of more than two hundred male residents of the village in 2007 showed a close genetic relation to the Han Chinese populace and a great deviation from the Western Eurasian gene pool.[40] The researchers conclude that the people of Liqian are probably of Han Chinese origin.[40] Moreover, the area lacks clear archaeological evidence of a Roman presence.[37][38][39]

A new hypothesis (Greek Hoplites in an Ancient Chinese Siege, Journal of Asian History) from 2011 by Dr Christopher Anthony Matthew from the Australian Catholic University[41] suggests that these strange warriors were no Roman legionaries with their testudo formation, but maybe Greek-Macedonian descendants of Alexander the Great’s army, that still fought as hoplites in phalanx formation.[42]

See also

- Indo-Roman relations

- The Malay Chronicles: Bloodlines, a movie based on the Sino-Roman relations

Footnotes

- ↑ Hill (2009), p. 5.

- ↑ Pulleyblank (1999), p. 77f.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hill (2009), p. 27.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Pulleyblank (1999), p. 78

- ↑ J. Thorley: "The Silk Trade between China and the Roman Empire at Its Height, 'Circa' A. D. 90-130", Greece & Rome,Vol. 18, No. 1 (1971), pp. 71-80

- ↑ Schoff (1915), p. 237

- ↑ Pulleyblank (1999), p. 71

- ↑ "Cathay and the way thither" by Henry Yule p.18

- ↑ Hill (2009), pp. 5, 481-483.

- ↑ Hill (2009), p. xx.

- ↑ Hill (2009), pp. 23, 25.

- ↑ Hill, John. (2012) Through the Jade Gate: China to Rome 2nd edition, p. 55. In press.

- ↑ His "Macedonian" origin betokens no more than his cultural affinity, and the name Maës is Semitic in origin (Cary 1956:130).

- ↑ The mainstream opinion, noted by Cary 1956:130 note 7, based on the date of Marinus, established by his use of many Trajanic foundation names but none identifiable with Hadrian.

- ↑ This is Cary's dating.

- ↑ Centuries later Tashkurgan ('Stone Tower') was the capital of the Pamir kingdom of Sarikol.

- ↑ Hill (2009), pp. xiii, 396,

- ↑ Stein (1907), pp. 44-45.

- ↑ Stein (1933), pp. 47, 292-295.

- ↑ Hill (2009), p. 27 and nn. 12.18 and 12.20.

- ↑ Hirth (1885), pp. 47-48.

- ↑ See http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/eastasia/romchin1.html

- ↑ Mango, Marlia Mundell. Byzantine Trade: Local, Regional, Interregional, and International See http://www.gowerpublishing.com/pdf/SamplePages/Byzantine_Trade_4th_12th_Centuries_Ch1.pdf

- ↑ Thorley (1971), pp. 71-80.

- ↑ Hill (2009), Appendix B - Sea Silk, pp. 466-476.

- ↑ Schoff (1915), p. 229

- ↑ John Thorley: "The Roman Empire and the Kushans", Greece & Rome, Vol. 26, No. 2 (1979), pp. 181-190 (187f.)

- ↑ Thorley (1971), pp. 71-80 (76)

- ↑

- ↑ Roman social history by Tim G. Parkin p.289 . Original Latin: "minimaque computatione miliens centena milia sestertium annis omnibus India et Seres et paeninsula illa imperio nostro adimunt: tanti nobis deliciae et feminae constant. quota enim portio ex illis ad deos, quaeso, iam vel ad inferos pertinet?" .

- ↑ Hill (2009), p. 291.

- ↑ Ferdinand von Richthofen, China, Berlin, 1877, Vol.I, pp.504-510; cited in Richard Hennig,Terrae incognitae : eine Zusammenstellung und kritische Bewertung der wichtigsten vorcolumbischen Entdeckungsreisen an Hand der daruber vorliegenden Originalberichte, Band I, Altertum bis Ptolemäus, Leiden, Brill, 1944, pp.387, 410-411; cited in Zürcher (2002), pp. 30-31.

- ↑ Milton Osborne, The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future (2001:25).

- ↑ Homer H. Dubs: "An Ancient Military Contact between Romans and Chinese", The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 62, No. 3 (1941), pp. 322-330

- ↑ Archaeology.org, Xinhua

- ↑ Ethan Gruber: The Origins of Roman Li-chien, 2007, pp. 18–21

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 China Daily: Hunt for Roman Legion Reaches China, 20 November 2010, retrieved 4 June 2012

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 The Daily Telegraph: Chinese Villagers 'Descended from Roman Soldiers', 23 November 2010, retrieved 4 Juni 2012

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Mail Online: DNA Tests Show Chinese Villagers with Green Eyes Could Be Descendants of Lost Roman Legion, 29 November 2010, retrieved 4 Juni 2012

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 R. Zhou et al.: Testing the Hypothesis of an Ancient Roman Soldier Origin of the Liqian People in Northwest China: a Y-Chromosome Perspective, in: Journal of Human Genetics, Vol. 52, No. 7 (2007), pp. 584–91

- ↑ Australian Catholic University - Dr Christopher Anthony Matthew

- ↑ History of the Ancient World - Descendants of Alexander the Great’s army fought in ancient China

References

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, First to Second Centuries CE. BookSurge. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hirth, Friedrich (1885): China and the Roman Orient. 1875. Shanghai and Hong Kong. Unchanged reprint. Chicago, Ares Publishers, 1975.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G.: "The Roman Empire as Known to Han China", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 119, No. 1 (1999), pp. 71–79

- Schoff, Wilfred H.: "The Eastern Iron Trade of the Roman Empire", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 35 (1915), pp. 224–239.

- Stein, Aurel M. (1907), Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan. 2 vols. pp. 44–45. M. Aurel Stein. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- Stein, Aurel M. (1932), On Ancient Central Asian Tracks: Brief Narrative of Three Expeditions in Innermost Asia and Northwestern China, pp. 47, 292-295. Reprinted with Introduction by Jeannette Mirsky. Book Faith India, Delhi. 1999.

- Thorley, J. (1971), The Silk Trade between China and the Roman Empire at Its Height, 'Circa' A. D. 90-130, Greece & Rome,Vol. 18, No. 1 (1971), pp. 71–80

- Yule, Henry. Cathay and the Way Thither. 1915.

- Zürcher, Erik (2002): "Tidings from the South, Chinese Court Buddhism and Overseas Relations in the Fifth Century AD." Erik Zürcher in: A Life Journey to the East. Sinological Studies in Memory of Giuliano Bertuccioli (1923-2001). Edited by Antonio Forte and Federico Masini. Italian School of East Asian Studies. Kyoto. Essays: Volume 2, pp. 21–43.

Further reading

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265. Draft annotated English translation.

- Leslie, D. D., Gardiner, K. H. J.: "The Roman Empire in Chinese Sources", Studi Orientali, Vol. 15. Rome: Department of Oriental Studies, University of Rome, 1996

- Schoff, Wilfred H.: "Navigation to the Far East under the Roman Empire", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 37 (1917), pp. 240–249

External links

- Accounts of "Daqin" (Roman Empire) in the Chinese history of the Later Han Dynasty

- Silk-road.com: The First Contact Between Rome and China

- Duncan B. Campbell: Romans in China?

| ||||||||||