Simon Templar

| Simon Templar | |

|---|---|

| The Saint character | |

The sign of The Saint, which appears on virtually every edition of every Simon Templar adventure. | |

| First appearance | Meet the Tiger |

| Created by | Leslie Charteris |

| Portrayed by |

Louis Hayward George Sanders Vincent Price Roger Moore Ian Ogilvy Simon Dutton Val Kilmer Tom Conway Edgar Barrier Brian Aherne Hugh Sinclair others |

| Information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation |

Thief amateur detective occasional police agent |

| Nationality | British |

Simon Templar is a British fictional character known as The Saint. He featured in a long-running series of books by Leslie Charteris published between 1928 and 1963. After that date, other authors collaborated with Charteris on books until 1983; two additional works produced without Charteris’s participation were published in 1997. The character has also been portrayed in motion pictures, radio dramas, comic strips, comic books and three television series.

Overview

Simon Templar is a Robin Hood-like criminal known as The Saint — plausibly from his initials; but the exact reason for his nickname is not known (although we're told that he was given it at the age of nineteen). Templar has aliases, often using the initials S.T. such as "Sebastian Tombs" or "Sugarman Treacle". Blessed with boyish humor, he makes humorous and off-putting remarks and leaves a "calling card" at his "crimes", a stick figure of a man with a halo. This is used as the logo of the books, the movies, and the 1960s TV series. He is described as "buccaneer in the suits of Savile Row, amused, cool, debonair, with hell-for-leather blue eyes and a saintly smile..."[1]

His origin remains a mystery, but in the books his income derives from the pockets of the "ungodly" (as he terms those who live by a lesser moral code than his own), whom he is given to "socking on the boko". There are references to a "ten percent collection fee" to cover expenses when he extracts large sums from victims, the remainder being returned to the owners, given to charity, shared among Templar's colleagues, or some combination of those possibilities.

Templar's targets include corrupt politicians, warmongers, and other low life. "He claims he's a Robin Hood", bleats one victim, "but to me he's just a robber and a hood".[2] Robin Hood appears one inspiration for the character; Templar stories were often promoted as featuring "The Robin Hood of modern crime", and this phrase to describe Templar appears in several stories. A term used by Templar to describe his acquisitions is "boodle" (a term also applied to the short story collection).

The Saint has a dark side, as he is willing to ruin the lives of the "ungodly", and even kill them, if he feels more innocent lives can be saved. In the early books, Templar refers to this as murder, although he considers his actions justified and righteous, a view usually shared by partners and colleagues. Several adventures centre on his intention to kill (for example, "Arizona" in The Saint Goes West has Templar planning to kill a Nazi scientist).

During the 1920s and early 1930s, The Saint is fighting European arms dealers, drug runners, and white slavers while based in his London home. His battles with Rayt Marius mirror the 'four rounds with Carl Petersen' of Bulldog Drummond. During the first half of the 1940s, Charteris cast Templar as a willing operative of the American government, fighting Nazi interests in the U.S. during World War II.

Beginning with the "Arizona" novella Templar is fighting his own war against Germany. The Saint Steps In reveals that Templar is operating on behalf of a mysterious American government official known as Hamilton who appears again in the next WWII-era Saint book, The Saint on Guard, and Templar is shown continuing to act as a secret agent for Hamilton in the first post-war novel, The Saint Sees it Through. The later books move from confidence games, murder mysteries, and wartime espionage and place Templar as a global adventurer.

According to Saint historian Burl Barer, Charteris made the decision to remove Templar from his usual confidence-game trappings, not to mention his usual co-stars Holm, Uniatz, Orace and Teal, as they weren't appropriate for the post-war stories he was writing.[3]

Although The Saint functions as an ordinary detective in some stories, others depict ingenious plots to get even with vanity publishers and other ripoff artists, greedy bosses who exploit their workers, con men, etc.

The Saint has many partners, though none last throughout the series. For the first half until the late 1940s, the most recurrent is Patricia Holm, his girlfriend, who was introduced in the first story, the 1928 novel Meet the Tiger in which she shows herself a capable adventurer. Holm appeared erratically throughout the series, sometimes disappearing for books at a time. Templar and Holm lived together in a time when common-law relationships were uncommon and, in some areas, illegal.

They have an easy, non-binding relationship, as Templar is shown flirting with other women from time to time. However, his heart remains true to Holm in the early books, culminating in his considering marriage in the novella The Melancholy Journey of Mr. Teal, only to have Holm say she had no interest in marrying. Holm disappeared in the late 1940s, and according to Barer's history of The Saint, Charteris refused to allow Templar a steady girlfriend, or Holm to return (although according to the Saintly Bible website, Charteris did write a film story that would have seen Templar encountering a son he had with Holm).

Another recurring character, Scotland Yard Inspector Claud Eustace Teal, could be found attempting to put The Saint behind bars, although in some books they work in partnership. In The Saint in New York, Teal's American counterpart, NYPD Inspector John Henry Fernack, was introduced, and he would become, like Teal, an Inspector Lestrade-like foil and pseudo-nemesis in a number of books, notably the American-based World War II novels of the 1940s.

The Saint had a band of compatriots, including Roger Conway, Norman Kent, Archie Sheridan, Richard "Dicky" Tremayne (a name that appeared in the 1990s TV series, Twin Peaks), Peter Quentin, Monty Hayward, and his ex-military valet, Orace.

In later stories, the dimwitted and constantly soused but reliable American thug Hoppy Uniatz was at Templar's side. Of The Saint's companions, only Norman Kent was killed during an adventure (he sacrifices himself to save Templar in the novel The Last Hero); the other males are presumed to have settled down and married (two to former female criminals: Dicky Tremayne to "Straight Audrey" Perowne and Peter Quentin to Kathleen "The Mug" Allfield; Archie Sheridan is mentioned to have married in "The Lawless Lady" in Enter the Saint, presumably to Lilla McAndrew after the events of the story "The Wonderful War" in Featuring the Saint).

Charteris gave Templar interests and quirks as the series went on. Early talents as an amateur poet and songwriter were displayed, often to taunt villains, though the novella The Inland Revenue established that poetry was also a hobby. That story revealed that Templar wrote an adventure novel featuring a South American hero not far removed from The Saint himself.

Templar also on occasion would break the fourth wall in an almost metafictional sense, making references to being part of a story and mentioning in one early story how he cannot be killed so early on; the 1960s television series would also have Templar address viewers. Charteris breaks the fourth wall by making references to the "chronicler" of The Saint's adventures and in one instance (the story "The Sizzling Saboteur" in The Saint on Guard) inserts his own name.

Publishing history

The origins of The Saint can be found in early works by Charteris, some of which predated the first Saint novel, 1928's Meet the Tiger, or were written after it but before Charteris committed to writing a Saint series. Burl Barer reveals that an obscure early work, Daredevil, not only featured a heroic lead who shared "Saintly" traits (down to driving the same brand of automobile) but also shared his adventures with Inspector Claud Eustace Teal—a character later a regular in Saint books. Barer writes that several early Saint stories were rewritten from non-Saint stories, including the novel She Was a Lady, which appeared in magazine form featuring a different lead character.

Charteris utilized three formats for delivering his stories. Besides full-length novels, he wrote novellas for the most part published in magazines and later in volumes of two or three stories. He also wrote short stories featuring the character, again mostly for magazines and later compiled into omnibus editions. In later years these short stories carried a common theme, such as the women Templar meets or exotic places he visits. With the exception of Meet the Tiger, chapter titles of Templar novels usually contain a descriptive phrase describing the events of the chapter; for example, Chapter Four of Knight Templar is entitled "How Simon Templar dozed in the Green Park and discovered a new use for toothpaste".

Although Charteris’s novels and novellas had more conventional thriller plots than his confidence game short stories, both novels and stories are admired. As in the past, the appeal lies in the vitality of the character, a hero who can go into a brawl and come out with his hair combed and who, faced with death, lights a cigarette and taunts his enemy with the signature phrase "As the actress said to the bishop...."

The period of the books begins in the 1920s and moves to the 1970s as the 50 books progress (the character being seemingly ageless). In early books most activities are illegal, although directed at villains. In later books, this becomes less so. In books written during World War II, The Saint was recruited by the government to help track spies and similar undercover work.[4] Later he became a cold warrior fighting Communism. The quality of writing also changes; early books have a freshness which becomes replaced by cynicism in later works. A few Saint stories crossed into science fiction and fantasy, "The Man Who Liked Ants" and the early novel The Last Hero being examples. When early Saint books were republished in the 1960s to the 1980s, it was not uncommon to see freshly written introductions by Charteris apologizing for the out-of-date tone; according to a Charteris "apology" in a 1969 paperback of Featuring the Saint, he attempted to update some earlier stories when they were reprinted but gave up and let them sit as period pieces. The 1963 edition of the short story collection The Happy Highwayman contains examples of abandoned revisions; in one story published in the 1930s ("The Star Producers"), references to actors of the 1930s were replaced for 1963 with names of current movie stars; another 1930s-era story, "The Man Who Was Lucky", added references to atomic power.

Charteris started retiring from writing books following 1963's The Saint in the Sun. The next book to carry Charteris’s name, 1964's Vendetta for the Saint, was written by science fiction author Harry Harrison, who had worked on the Saint comic strip, after which Charteris edited and revised the manuscript. Between 1964 and 1983, another 14 Saint books would be published, credited to Charteris but written by others. In his introduction to the first, The Saint on TV, Charteris called these volumes a team effort in which he oversaw selection of stories, initially adaptations of scripts written the 1962–69 TV series The Saint, and with Fleming Lee writing the adaptations (other authors took over from Lee). Charteris and Lee collaborated on two Saint novels in the 1970s, The Saint in Pursuit (based on a story by Charteris for the Saint comic strip) and The Saint and the People Importers. The "team" writers were usually credited on the title page, if not the cover. One later volume, Catch the Saint, was an experiment in returning The Saint to his period, prior to the Second World War (as opposed to recent Saint books set in the present day).

The last Saint volume in the line of books starting with Meet the Tiger in 1928 was Salvage for the Saint, published in 1983. According to the Saintly Bible website, every Saint book published between 1928 and 1983 saw the first edition issued by Hodder and Stoughton in the UK (a company that originally published only religious books) and The Crime Club (an imprint of Doubleday that specialized in mystery and detective fiction) in the United States. For the first 20 years, the books were first published in Britain, with the U.S. edition following up to a year later. By the late 1940s to early 1950s, this situation had been reversed. In one case—The Saint to the Rescue—a British edition did not appear until nearly two years after the American one.

French language books published over 30 years included translated volumes of Charteris originals as well as novelisations of radio scripts from the English-language radio series and comic strip adaptations. Many of these books credited to Charteris were written by others, including Madeleine Michel-Tyl.[5]

Charteris died in 1993. Two additional Saint novels appeared around the time of the 1997 film starring Val Kilmer: a novelisation of the film (which had little connection to the Charteris stories) and Capture the Saint, a more faithful work published by The Saint Club and originated by Charteris in 1936. Both books were written by Burl Barer, who in the early 1990s published a history of the character in books, radio, and television.

Charteris wrote 14 novels between 1928 and 1971 (the last two co-written), 34 novellas, and 95 short stories featuring Simon Templar. Between 1963 and 1997, an additional seven novels and fourteen novellas were written by others.

The Saint on radio

Several radio drama series were produced in North America, Ireland, and Britain. The earliest was for Radio Eireann's Radio Athlone in 1940 and starred Terence De Marney. Both NBC and CBS produced Saint series during 1945, starring Edgar Barrier and Brian Aherne. Many early shows were adaptations of published stories, although Charteris wrote several storylines for the series which were novelised as short stories and novellas.

The longest-running radio incarnation was Vincent Price, who played the character in a series between 1947 and 1951 on three networks: CBS, Mutual and NBC. Like The Whistler, the program had an opening whistle theme with footsteps. Some sources say the whistling theme for The Saint was created by Leslie Charteris while others credit RKO composer Roy Webb.

Price left in May 1951, replaced by Tom Conway, who played the role for several more months. His brother, George Sanders, had played Templar on film. The next English-language radio series aired on Springbok Radio in South Africa between 1953 and 1957. These were fresh adaptations of the original stories and starred Tom Meehan. Around 1965–66 the South African version of Lux Radio Theatre produced a single dramatization of The Saint. The English service of South Africa produced another series radio adventures for six months in 1970–1971. The next English-language incarnation was a series of three radio plays on BBC Radio 4 in 1995 starring Paul Rhys.

The Saint in film and on TV

Not long after creating The Saint, Charteris began a long association with Hollywood as a screenwriter. He was successful in getting a major studio, RKO Radio Pictures, interested in a film based on one of his works. The first, The Saint in New York in 1938, based on the 1935 novel of the same name, starred Louis Hayward as Templar and Jonathan Hale as Inspector Henry Farnack, the American counterpart of Mr Teal.

The film was a success and seven more films followed in quick succession. George Sanders took over the lead role from Hayward and did it for five of those films, while Hugh Sinclair portrayed Templar in the two last. Several of the films were original stories, sometimes based upon outlines by Charteris while others were based loosely on original novels or novellas.

In 1953, British Hammer Film Productions produced The Saint's Return (known as "The Saint's Girl Friday" in the US), for which Hayward returned to the role. This was followed by an unsuccessful French production in 1960.

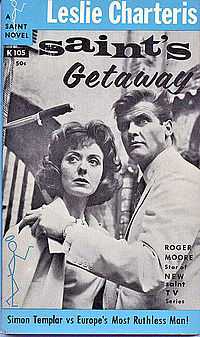

In the 1960s Roger Moore, who strongly resembled Louis Hayward in the 1930s, revived the role in a long-running television series The Saint. According to the book Spy Television by Wesley Britton, the first actor offered the role was Patrick McGoohan of Danger Man and The Prisoner. The series ran from 1962 to 1969, and Moore remains the actor most closely identified with the character.

Since Moore, other actors played him in later series, notably Return of the Saint (1978–1979) starring Ian Ogilvy; the series ran for one season, although it was picked up by the CBS Network. In the mid-1980s, the National Enquirer and other newspapers reported that Moore was planning to produce a movie based on The Saint with Pierce Brosnan as Templar, but it was never made. (Ironically Brosnan almost became Moore's immediate successor as James Bond.) A pilot for a The Saint in Manhattan series starring Australian actor Andrew Clarke was shown on CBS in 1987 as part of the CBS Summer Playhouse; the pilot was produced by Don Taffner, but it never progressed beyond the pilot stage. Inspector John Fernack of the NYPD, played by Kevin Tighe, made his first film appearance since the 1940s in that production, while Templar (sporting a moustache) got about in a black Lamborghini bearing the ST1 licence plate. In 1989, six movies were made by Taffner starring Simon Dutton. These were syndicated in the United States as part of a series of films entitled Mystery Wheel of Adventure, while in the UK they were shown as a series on ITV.

In 1991, as detailed by Burl Barer in his 1992 history of The Saint, plans were announced for a series of motion pictures. Ultimately, however, no such franchise appeared.

The Saint starring Val Kilmer was made in 1997 but diverged far from the Charteris books, although it did revive Templar's use of aliases. Kilmer's Saint is unable to defeat a Russian gangster in hand-to-hand combat and is forced to flee; this would have been unthinkable in a Charteris tale. Whereas the original Saint resorted to aliases that had the initials S.T., Kilmer's character used Christian saints, regardless of initials. This Saint refrained from killing, and even the main villains live to stand trial, whereas Charteris’s version had no qualms about taking another life. Kilmer's Saint is presented as a master of disguise, but Charteris’s version hardly used the sophisticated ones shown in this film. The film mirrored aspects of Charteris’s own life, notably his origins in the Far East, though not in an orphanage as the film portrayed. Sir Roger Moore features throughout in cameo as the BBC Newsreader heard in Simon Templar's Volvo.

Since the Kilmer film, there have been several failed attempts at producing pilots for potential new Saint television series:

On March 13, 2007, TNT said it was developing a one-hour series. The series (for which no broadcast date was announced) was to be executive produced by William J. MacDonald and produced by Jorge Zamacona.[6][7] James Purefoy was announced as the new Simon Templar.[8][9] Production of the pilot, which was to have been directed by Barry Levinson, did not go ahead.[10] Another attempt production was planned for 2009 with Scottish actor Dougray Scott starring as Simon Templar. Former Saint Roger Moore announced on his website that he would be appearing in the new production, which is being produced by his son, Geoffrey Moore, in a small role.[11] This production also did not proceed.

It was announced in December 2012 that a third attempt would be made to produce a pilot for a potential TV series. This time, English actor Adam Rayner was cast as Simon Templar and American actress Eliza Dushku as Patricia Holm (a character from the novels never before portrayed on television and only once in the films), with Roger Moore producing.[12] Unlike the prior attempts, production of the Rayner pilot did commence in December 2012 and continued into early 2013, with Moore and Ogilvy making cameo appearances, according to a cast list posted on the official Leslie Charteris website.[13]

Films

Since 1938, numerous films have been produced in the United States, France and Australia based to varying degrees upon The Saint. A few were based, usually loosely, upon Charteris’s stories, but most were original.

This is a list of the films featuring Simon Templar and of the actors who played The Saint:

- The Saint in New York (1938 – Louis Hayward)

- The Saint Strikes Back (1939 – George Sanders)

- The Saint in London (1939 – Sanders)

- The Saint's Double Trouble (1940 – Sanders)

- The Saint Takes Over (1940 – Sanders)

- The Saint in Palm Springs (1941 – Sanders)

- The Saint's Vacation (1941 – Hugh Sinclair)

- The Saint Meets the Tiger (produced in 1941, released in 1943 – Sinclair)

- The Saint's Return (1953 – Hayward) - aka The Saint's Girl Friday

- Le Saint mène la danse (1960 – Félix Marten)

- Le Saint prend l'affut (1966 – Jean Marais)

- The Fiction Makers (1968 – Roger Moore) – edited from episodes of The Saint

- Vendetta for the Saint (1969 – Moore) – edited from episodes of The Saint

- The Saint and the Brave Goose (1979 made for TV – Ian Ogilvy) – edited from episodes of Return of the Saint

- The Saint in Manhattan (1987 made for TV – Andrew Clarke)

- The Saint (1997 – Val Kilmer)

In the 1930s, RKO purchased the rights to produce a film adaptation of Saint Overboard, but no such movie was ever produced.

Television series

- This list only includes productions that became TV series, and does not include pilots.

- The Saint (1962–1969 – Roger Moore)

- Return of the Saint (1978–1979 – Ian Ogilvy)

- The made-for-TV film series that formed part of Mystery Wheel of Adventure (1989) – all starring Simon Dutton

- Fear in Fun Park (aka The Saint in Australia)

- The Big Bang

- The Blue Dulac

- The Brazilian Connection

- The Software Murders

- Wrong Number

Three of the surviving actors who have played Templar—Roger Moore, Ian Ogilvy, and Simon Dutton—have been appointed vice presidents of "The Saint Club" that was founded by Leslie Charteris himself in 1936.

The Saint on the stage

In the late 1940s Charteris and sometime Sherlock Holmes scriptwriter Denis Green wrote a stage play entitled The Saint Misbehaves.[14]

It was never publicly performed, as soon after writing it Charteris decided to focus on non-Saint work. For many years it was thought to be lost; however, two copies are known to exist in private hands, and correspondence relating to the play can be found in the Leslie Charteris Collection at Boston University.

The Saint in the comics

The Saint appeared in a long-running comic strip series starting as a daily strip 27 September 1948 with a Sunday added on 20 March the following year. The early strips were written by Leslie Charteris, who had previous experience writing comic strips, having replaced Dashiell Hammett as the writer of the Secret Agent X-9 strip. The original artist was Mike Roy. In 1951, when John Spranger replaced Roy as the artist, he altered The Saint's appearance by depicting him with a beard. Bob Lubbers illustrated The Saint in 1959 and 1960. The final two years of the strip were drawn by Doug Wildey before it came to an end on 16 September 1961.

Concurrent with the comic strip, Avon Comics published 12 issues of a The Saint comic book between 1947 and 1952 (some of these stories were reprinted in the 1980s). The 1960s TV series is unusual in that it is one of the few major programs of its genre that was not adapted as a comic book in the United States.

In Sweden, The Saint had a long-running comic book published from 1966 to 1985 under the title Helgonet.[15] It originally reprinted the newspaper strip, but soon original stories were commissioned for Helgonet. These stories were also later reprinted in other European countries. Two of the main writers were Norman Worker and Donne Avenell; the latter also co-wrote the novels The Saint and the Templar Treasure and the novella collection Count on the Saint, while Worker contributed to the novella collection Catch the Saint.

A new American comic book series was launched by Moonstone Comics in the summer of 2012.

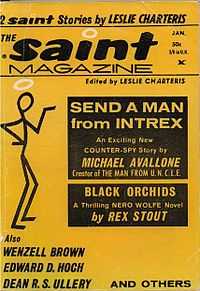

The Saint in magazines

Charteris also edited or oversaw several magazines that tied in with The Saint. The first of these were anthologies entitled The Saint's Choice that ran for seven issues in 1945–46. A few years later Charteris launched The Saint Detective Magazine (later titled The Saint Mystery Magazine and The Saint Magazine), which ran for 141 issues between 1953 and 1967, with a separate British edition that ran just as long but published different material. In most issues of Saint's Choice and the later magazines Charteris included at least one Saint story, usually previously published in one of his books but occasionally original. In several mid-1960s issues, however, he substituted Instead of the Saint, a series of essays on topics of interest to him. The rest of the material in the magazines consisted of novellas and short stories by other mystery writers of the day. An Australian edition was also published for a few years in the 1950s. In 1984 Charteris attempted to revive the Saint magazine, but it ran for only three issues.[16]

Leslie Charteris himself portrayed The Saint in a photo play in Life Magazine: The Saint Goes West.

The Saint book series

Most Saint books were collections of novellas or short stories, some of which were published individually either in magazines or in smaller paperback form. Many of the books have also been published under different titles over the years; the titles used here are the more common ones for each book.

From 1964 to 1983, the Saint books were collaborative works; Charteris acted in an editorial capacity and received front cover author credit, while other authors wrote these stories and were credited inside the book. These collaborative authors are noted.(Sources: Barer and the editions themselves.)

| Year | First publication title (and author if not Charteris) |

Stories | Alternative titles |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1928 | Meet the Tiger | novel | Meet - the Tiger! The Saint Meets the Tiger Scoundrels Ltd. Crooked Gold The Saint in Danger |

| 1930 | Enter the Saint | "The Man Who was Clever" "The Policeman with Wings" "The Lawless Lady" (Some editions contain only two stories, in different combinations) |

none |

| 1930 | The Last Hero | novel | The Creeping Death Sudden Death The Saint Closes the Case The Saint and the Last Hero |

| 1930 | Knight Templar | novel | The Avenging Saint |

| 1931 | Featuring the Saint (originally published UK only) |

"The Logical Adventure" "The Wonderful War" "The Man Who Could Not Die" |

none |

| 1931 | Alias the Saint (originally published UK only) |

"Story of a Dead Man" "The Impossible Crime" "The National Debt" Avon paperback contains only "The National Debt" and "The Man Who Could Not Die" from the previous book. |

none |

| 1931 | Wanted for Murder (US only) |

America-only edition combining Featuring the Saint and Alias the Saint (only US edition of these books until the 1960s) Avon paperback has only "The Story of a Dead Man" and "The Impossible Crime" from the previous book. |

none |

| 1931 | She Was a Lady | novel | The Saint Meets His Match Angels of Doom |

| 1932 | The Holy Terror | "The Inland Revenue" "The Million Pound Day" "The Melancholy Journey of Mr. Teal" |

The Saint Vs. Scotland Yard |

| 1932 | Getaway | novel | The Saint's Getaway Property of the Deceased Two Men from Munich |

| 1933 | Once More the Saint | "The Gold Standard" "The Man from St. Louis" "The Death Penalty" |

The Saint and Mr. Teal |

| 1933 | The Brighter Buccaneer | "The Brain Workers" "The Export Trade" "The Tough Egg" "The Bad Baron" "The Brass Buddha" "The Perfect Crime" "The Unpopular Landlord" "The New Swindle" "The Five Thousand Pound Kiss" "The Blind Spot" "The Unusual Ending" "The Unblemished Bootlegger" "The Appalling Politician" "The Owner's Handicap" "The Green Goods Man" |

none |

| 1934 | The Misfortunes of Mr. Teal | "The Simon Templar Foundation" "The Higher Finance" "The Art of Alibi" |

The Saint in London The Saint in England |

| 1934 | Boodle | "The Ingenious Colonel" "The Unfortunate Financier" "The Newdick Helicopter" "The Prince of Cherkessia" "The Treasure of Turk's Lane" "The Sleepless Knight" "The Uncritical Publisher" "The Noble Sportsman" "The Damsel in Distress" "The Loving Brothers" "The Tall Timber" "The Art Photographer" "The Man Who Liked Toys" "The Mixture as Before" (some editions omit the stories "The Uncritical Publisher" and "The Noble Sportsman") |

The Saint Intervenes |

| 1934 | The Saint Goes On | "The High Fence" "The Elusive Ellshaw" "The Case of the Frightened Innkeeper" |

none |

| 1935 | The Saint in New York | novel | none |

| 1936 | Saint Overboard | novel | The Pirate Saint The Saint Overboard |

| 1937 | The Ace of Knaves | "The Spanish War" "The Unlicensed Victuallers" "The Beauty Specialist" |

The Saint in Action |

| 1937 | Thieves' Picnic | novel | The Saint Bids Diamonds |

| 1938 | Prelude for War | novel | The Saint Plays with Fire The Saint and the Sinners |

| 1938 | Follow the Saint | "The Miracle Tea Party" "The Invisible Millionaire" "The Affair of Hogsbotham" |

none |

| 1939 | The Happy Highwayman | "The Man Who was Lucky" "The Smart Detective" "The Wicked Cousin" "The Well-Meaning Mayor" "The Benevolent Burglary" "The Star Producers" "The Charitable Countess" "The Mug's Game" "The Man Who Liked Ants" (some editions omit the stories "The Charitable Countess" and "The Mug's Game"; story order also varies between editions) |

none |

| 1940 | The Saint in Miami | novel | none |

| 1942 | The Saint Goes West | "Arizona" "Palm Springs" "Hollywood" (Some editions omit "Arizona") |

none |

| 1942 | The Saint Steps In | novel | none |

| 1944 | The Saint on Guard | "The Black Market" "The Sizzling Saboteur" (Some editions omit the second story, which is often published on its own) |

The Saint and the Sizzling Saboteur (single story reprint) |

| 1946 | The Saint Sees it Through | novel | none |

| 1948 | Call for the Saint | "The King of the Beggars" "The Masked Angel" |

none |

| 1948 | Saint Errant | "Judith: The Naughty Niece" "Iris: The Old Routine" "Lida: The Foolish Frail" "Jeannine: The Lovely Sinner" "Lucia: The Homecoming of Amadeo Urselli" "Teresa: The Uncertain Widow" "Luella: The Saint and the Double Badger" "Emily: The Doodlebug" "Dawn: The Darker Drink" |

none |

| 1953 | The Saint in Europe | "Paris: The Covetous Headsman" "Amsterdam: The Angel's Eye" "The Rhine: The Rhine Maiden" "Tirol: The Golden Journey" "Lucerne: The Loaded Tourist" "Jaune-les-Pins: The Spanish Cow" "Rome: The Latin Touch" |

none |

| 1955 | The Saint on the Spanish Main | "Bimini: The Effete Angler" "Nassau: The Arrow of God" "Jamaica: The Black Commissar" "Puerto Rico: The Unkind Philanthropist" "Virgin Islands: The Old Treasure Story" "Haiti: The Questing Tycoon" (some editions contain only 4 stories) |

none |

| 1956 | The Saint Around the World | "Bermuda: The Patient Playboy" "England: The Talented Husband" "France: The Reluctant Nudist" "Middle East: The Lovelorn Sheik" "Malaya: The Pluperfect Lady" "Vancouver: The Sporting Chance" |

none |

| 1957 | Thanks to the Saint | "The Bunco Artists" "The Happy Suicide" "The Good Medicine" "The Unescapable Word" "The Perfect Sucker" "The Careful Terrorist" |

none |

| 1958 | Señor Saint | "The Pearls of Peace" "The Revolution Market" "The Romantic Matron" "The Golden Frog" |

none |

| 1959 | The Saint to the Rescue | "The Ever-Loving Spouse" "The Fruitful Land" "The Percentage Player" "The Water Merchant" "The Gentle Ladies" "The Element of Doubt" |

none |

| 1962 | Trust the Saint | "The Helpful Pirate" "The Bigger Game" "The Cleaner Cure" "The Intemperate Reformer" "The Uncured Ham" "The Convenient Monster" |

none |

| 1963 | The Saint in the Sun | "Cannes: The Better Mousetrap" "St. Tropez: The Ugly Impresario" "England: The Prodigal Miser" "Nassau: The Fast Women" "Florida: The Jolly Undertaker" "Lucerne: The Russian Prisoner" "Provence: The Hopeless Heiress" |

none |

| 1964 | Vendetta for the Saint (Harry Harrison, Leslie Charteris) |

novel | none |

| 1968 | The Saint on TV (Fleming Lee, John Kruse) |

"The Death Game" "The Power Artist" (novelisation of TV scripts) |

none |

| 1968 | The Saint Returns (Fleming Lee, John Kruse, D.R. Motton, Leigh Vance) |

"The Dizzy Daughter" "The Gadget Lovers" (novelisation of TV scripts) |

none |

| 1968 | The Saint and the Fiction Makers (Fleming Lee, John Kruse) |

novelisation of TV script | none |

| 1969 | The Saint Abroad (Fleming Lee, Michael Pertwee) |

"The Art Collectors" "The Persistent Patriots" (novelisation of TV scripts) |

none |

| 1970 | The Saint in Pursuit (Fleming Lee, Leslie Charteris) |

novelization of comic strip | none |

| 1971 | The Saint and the People Importers (Fleming Lee, Leslie Charteris) |

novelisation of TV script | none |

| 1975 | Catch the Saint (Fleming Lee, Norman Worker) |

"The Masterpiece Merchant" "The Adoring Socialite" |

none |

| 1976 | The Saint and the Hapsburg Necklace (Christopher Short) |

novel | none |

| 1977 | Send for the Saint (Peter Bloxsom, John Kruse, Donald James) |

"The Midas Double" "The Pawn Gambit" |

none |

| 1978 | The Saint in Trouble (Graham Weaver, John Kruse, Terence Feely) |

"The Imprudent Professor" (Return of the Saint episode novelisation) "The Red Sabbath" |

none |

| 1979 | The Saint and the Templar Treasure (Graham Weaver, Donne Avenell) |

novel | none |

| 1980 | Count on the Saint (Graham Weaver, Donne Avenell) |

"The Pastors' Problem" "The Unsaintly Santa" |

none |

| 1983 | Salvage for the Saint (Peter Bloxsom, John Kruse) |

novel (Return of the Saint episode novelisation) |

none |

| 1997 | The Saint (Burl Barer, Jonathan Hensleigh, Wesley Strick) |

film novelization | none |

| 1997 | Capture the Saint (Burl Barer) |

novel | none |

Omnibus editions

| Year | First publication title | Stories | From |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | The First Saint Omnibus | The Man Who was Clever The Wonderful War The Story of a Dead Man The Unblemished Bootlegger The Appalling Politician The Million Pound Day The Death Penalty The Simon Templar Foundation The Unfortunate Financier The Sleepless Knight The High Fence The Unlicensed Victuallers The Affair of Hogsbotham |

Enter the Saint Featuring the Saint Alias the Saint The Brighter Buccaneer The Brighter Buccaneer The Holy Terror Once More the Saint The Misfortunes of Mr Teal Boodle Boodle The Saint Goes On The Ace of Knaves Follow the Saint |

| 1952 | The Second Saint Omnibus | The Star Producers The Wicked Cousin The Man Who Liked Ants Palm Springs The Sizzling Saboteur The Masked Angel Judith Jeannine Teresa Dawn |

The Happy Highwayman The Happy Highwayman The Happy Highwayman The Saint Goes West The Saint On Guard Call For The Saint Saint Errant Saint Errant Saint Errant Saint Errant |

French adventures

A number of Saint adventures were published in French over a 30-year period, many of which have yet to be published in English. Many of these stories were ghostwritten by Madeleine Michel-Tyl and credited to Charteris (who exercised some editorial control). The French books were generally novelisations of scripts from the radio series, or novels adapted from stories in the American Saint comic strip. One of the writers who worked on the French series, Fleming Lee, later wrote for the English-language books.[5]

Unpublished works

Burl Barer's history of The Saint identifies two manuscripts that to date have never been published. The first is a collaboration between Charteris and Fleming Lee called Bet on the Saint that was rejected by Doubleday, the American publishers of the Saint series. Charteris, Barer writes, chose not to submit it to his UK publishers, Hodder & Stoughton. The rejection of the manuscript by Doubleday meant that The Crime Club's long-standing right of first refusal on any new Saint works was now ended and the manuscript was then submitted to other U.S. publishers, without success. Barer also tells of a 1979 novel entitled The Saint's Lady by a Scottish fan, Joy Martin, which had been written as a present for and as a tribute to Charteris. Charteris was impressed by the manuscript and attempted to get it published, but it too was ultimately rejected. The manuscript, which according to Barer is in the archives of Boston University, features the return of Patricia Holm.

According to the Saintly Bible website, at one point Leslie Charteris biographer (Ian Dickerson) was working on a manuscript (based upon a film story idea by Charteris) for a new novel entitled Son of the Saint in which Templar shares an adventure with his son by Patricia Holm. The book has, to date, not been published.[17]

References

- ↑ Leslie Charteris. She Was a Lady. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1931, p. 26

- ↑ The Sporting Chance in The Saint Around the World

- ↑ Burl Barer, The Saint : A Complete History in Print, Radio, Film and Television of Leslie Charteris' Robin Hood of Modern Crime, Simon Templar 1928-1992. Jefferson, N.C.: MacFarland, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7864-1680-6. OCLC 249331526.

- ↑ Templar's behind-the-scenes work for the war effort, only hinted at initially, is confirmed in The Saint Steps In (The Crime Club, 1942)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 The Saint Novels in French

- ↑ TNT, Devil team for 'Leverage' – Entertainment News, TV News, Media – Variety

- ↑ Burl Barer, Brilliant Author: THE SAINT on TNT

- ↑ Lesliecharteris.com

- ↑ James Purefoy To Play Simon Templar in The Saint – The Saint and Leslie Charteris Blog

- ↑ The Hollywood Reporter: "James Purefoy circles NBC series, July 21, 2008. Accessed August 5, 2008.

- ↑ Roger-moore.com

- ↑ Andreeva, Nellie (2012-12-10). "Eliza Dushku To Co-Star In ‘The Saint’ Backdoor Pilot, Roger Moore To Co-Produce". deadline.com. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ↑ "News - December 17, 2012". lesliecharteris.com. 2012-12-17. Retrieved 2013-01-21.

- ↑ Could the Saint Build a Better Mousetrap? ~ at Runboard.com

- ↑ sv:Helgonet (serietidning)

- ↑ The Saint (Detective/Mystery) Magazine

- ↑ The Saint and Leslie Charteris FAQ

External links

- The Saintly Bible: large website about Leslie Charteris’s creation (including news blog)

- Official Website for Leslie Charteris

- The Saint Novels in French

- Listing of all English-language Saint radio programs

- Public domain recordings of Saint radio episodes in MP3 format, starring Vincent Price.

- Sir Roger Moore – A Fan Site