Simon Forman

| Simon Forman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

31 December 1552 Quidhampton, Wiltshire, England |

| Died |

5 or 12 September 1611 River Thames, London |

Resting place | St Mary, Lambeth |

| Residence | Lambeth |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Salisbury grammar school |

| Alma mater | Magdalen College, Oxford |

| Occupation |

astrologer alchemist medical practitioner |

| Known for |

Extensive records of astrological practice, Eye-witness accounts of plays by William Shakespeare Alleged complicity in murder of Sir Thomas Overbury |

| Spouse(s) | Jean Baker |

Simon Forman (31 December 1552 – 5 or 12 September 1611) was an Elizabethan astrologer, occultist and herbalist active in London during the reigns of Queen Elizabeth I and James I of England. His reputation, however, was severely tarnished after his death when he was implicated in the plot to kill Sir Thomas Overbury. Writers from Ben Jonson to Nathaniel Hawthorne came to characterize him as either as a fool or an evil magician in league with the devil.

Life

Forman was born in Quidhampton, Fugglestone St Peter, near Salisbury, Wiltshire, on 31 December 1552.[1][2] At the age of nine he went to a free school in the Salisbury area but was forced to leave after two years following the death of his father on 31 December 1563. For the next ten years of his life he was apprenticed to Matthew Commin, a local merchant. Commin traded in cloth, salt and herbal medicines, and it was during his time as a young apprentice that Forman started to learn about herbal remedies. After arguments with Mrs Commin, Simon found his apprenticeship terminated, and he moved to Oxford to live with cousins. He then spent a year and a half at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he studied chiefly medicine and astrology, continuing the same studies in Holland.

Through the 1570s and 1580s Forman worked as a teacher while studying the occult arts. In 1583 he moved to London starting up a practice as a physician in Philpot Lane, Westminster. Having survived an outbreak of the plague in the city that year and again in 1594 his medical reputation began to spread. Around this time a Buckinghamshire clergyman named Richard Napier (1559 – 1634) became his protégé. From 1597 he began to develop a more serious interest in the occult [3] eventually setting up an alternative medical practice in Billingsgate, providing astrologically-based remedies keeping detailed casebooks of his clients' questions about illness, pregnancy, stolen goods, career opportunities and marriage prospects. In his new office he was able to fulfill the role of both physician and surgeon (seen as two very separate professions by his medical peers). This unorthodox practice, however, soon attracted the attention of the Company of Barber-Surgeons (now the Royal College of Surgeons of England) who successfully banned him from medical practice. Since he possessed no diploma, and following the death of one of his patients, Forman served several prison sentences. He continued to dispute with the Company of Barber-Surgeons, eventually obtaining a license to practice from the University of Cambridge in 1603.

With a notable sexual appetite, Forman was said to have pressed himself upon nearly every women he met. Forman himself wrote of his conquests in his diaries, showing as little regard for the background of his inamoratas as for the location of consummation. Many of his clients provided brief affairs. He wrote of having his first sex with his "beloved" on 15/12/1593, 5:00 PM, London." Then writing after "She died 13/6/1597." On 22 July 1599, Forman wed seventeen year-old Jane Baker, a girl renting a room in his house in Lambeth. Having never been content with just one woman, the marriage sadly, “did not make much difference to (his) way of life, except that he had an inexperienced girl now as mistress of the house; he continued to be master.”[4] In 1611, he accurately predicted his own death on the River Thames. Another astrologer, William Lilly, reports that one warm Sunday afternoon in September of that year, Forman told his wife that he would die the following Thursday night (12 September). And, sure enough:

Monday came, all was well. Tuesday came, he not sick. Wednesday came, and still he was well; with which his impertinent wife did much twit him in his teeth. Thursday came, and dinner was ended, he very well: he went down to the water-side, and took a pair of oars to go to some buildings he was in hand with in Puddle-dock. Being in the middle of the Thames, he presently fell down, only saying, 'An impost, an impost,' and so died. A most sad storm of wind immediately following.[5]

After his death he was implicated in the murder of Thomas Overbury through his association with his two patients, Lady Frances Howard, and Mrs Anne Turner. During the testimony of Howard's trial, lawyers hurled accusations at Forman, claiming that he had given Lady Essex the potion with which she plotted to kill Overbury. During the trial he was described by Sir Edward Coke, Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench as the 'Devil Forman'; the result being that his reputation was severely tarnished.

Work

Forman's papers have proven to be a treasure trove of rare, odd, unusual data on one of the most studied periods of cultural history. They include autobiographies, guides to astrology, plague tracts, alchemical commonplace books and notes on biblical and historical subjects. They also contain his disputes with the Company of Barber-Surgeons and his largely unsuccessful magical experiments. At one time he possessed the copy of the Picatrix currently in the British Library. Forman left behind a large body of manuscripts dealing with his patients and with all the subjects that interested him, from astronomy and astrology to medicine, mathematics, and magic. His Casebook is the most famous of these resources, though he also produced diaries and a third-person autobiography. His only printed work was a pamphlet advertising a bogus method for divining the longitude while at sea.

His intimate knowledge of Shakespeare's circle makes him especially attractive to literary historians. Modern scholars—A. L. Rowse is one prominent example,[6] and others have followed his lead—have exploited Forman's manuscripts for the manifold lights they throw on the less-exposed private lives of Elizabethan and Jacobean men and women. One of Forman's patients was the poet Emilia Lanier, Rowse's candidate to have been Shakespeare's Dark Lady; another patient was Mrs Mountjoy, Shakespeare's landlady. Sixty-four volumes of his manuscripts were collected by Elias Ashmole in the seventeenth century, and are now held in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Others can be found in the Plymouth Library. A Brief Description of the Forman MSS. in the Public Library, Plymouth, was published in 1853.

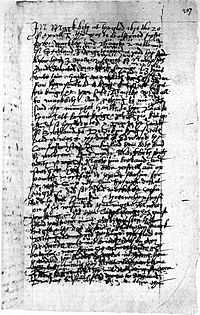

The "Book of Plays"

Among Forman's manuscripts is a section titled the "Bocke of Plaies," which records Forman's descriptions of four plays he saw in 1610-11 and the morals he drew from them. The document is noteworthy for the listing of three Shakespearean performances: Macbeth at the Globe Theatre on 20 April 1610;[7] The Winter's Tale at the Globe on 15 May 1611; and Cymbeline, date and theatre not specified. The fourth play described by Forman is a Richard II acted at the Globe on 30 April 1611; but from the description it is clearly not Shakespeare's Richard II. The manuscript was first described by John Payne Collier in 1836, and in the 20th century it was suspected as one of his forgeries.[8] Most modern scholars now accept the section as authentic,[9] but some still suspect it could be a forgery.[10]

References in fiction

Simon Forman is the protagonist of the Elizabethan mystery series by Judith Cook, The Casebook of Dr Simon Forman—Elizabethan doctor and solver of mysteries. These well-researched mysteries are based on the original casebook manuscripts, and contain a mix of historical and fictional characters.

Notes

- ↑

"Forman, Simon". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Forman, Simon". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - ↑ Ann Hoffman, Lives of the Tudor age, 1485-1603 (1977), p. 177

- ↑ http://www.hps.cam.ac.uk/casebooks/formancasebooks.html

- ↑ Rowse, p. 93

- ↑ William Lilly's History of his Life and Times; pp.43-44. Reproduced online at Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ↑ Rowse's books Shakespeare the Man (London, MacMillian, 1973) and Sex and Society in Shakespeare's Age: Simon Forman the Astrologer (New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1974) draw heavily on Forman sources.

- ↑ Scholars, critics, and editors usually assume that this "1610" is a mistake for "1611," and that the whole of the Book of Plays most likely dates from that year. See: E.K. Chambers, William Shakespeare, Oxford: Oxford UP, 1930, 2: 337.

- ↑ Altick, Richard D. The Scholar Adventurers, Columbus: Ohio State UP, 1950, 1987: 155-159.

- ↑ Schoenbaum, S. William Shakespeare: Records and Images, New York: Oxford UP, 1981, pp. 16, 20.

- ↑ Wagner, John A., Voices of Shakespeare's England: Contemporary Accounts of Elizabethan Daily Life, pg 143., Greenwood Publishing, 2010.

References

- Judith Cook, Blood on the Borders: The Casebook of Dr. Simon Forman–Elizabethan Doctor and Solver of Mysteries, London, Headline, 1999.

- Judith Cook, Dr. Simon Forman: A Most Notorious Physician, London, Chatto & Windus, 2001.

- Lauren Kassell, Medicine and Magic in Elizabethan London: Simon Forman, Astrologer, Alchemist, and Physician, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Barbara Howard Traister, The Notorious Astrological Physician of London: Works and Days of Simon Forman, Chicago and London, University of Chicago Press, 2001.

External links

- Extracts from Forman's Metrical Autobiography with other notes (published 1853).

- "Forman, Simon (FRMN604S)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- The Casebooks Project, an electronic edition of the casebooks of the 50,000 astrological consultations that Simon Forman and Richard Napier conducted between 1596 and 1634.

|