Sikhism

| Sikhism |

|---|

This article is part of a series on Sikhism |

| Sikh Gurus |

|

| Philosophy |

|

| Practices |

|

| Scripture |

|

| General topics |

|

|

|

Sikhism, or known in Punjabi as Sikhi,[note 1] (/ˈsiːkɨzəm/ or /ˈsɪkɨzəm/; Punjabi: ਸਿੱਖੀ, sikkhī, IPA: [ˈsɪkːʰiː]) is a monotheistic religion founded during the 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, by Guru Nanak[1] and continued to progress through the ten successive Sikh gurus (the eleventh and last guru being the holy scripture Guru Granth Sahib. The Guru Granth Sahib is a collection of the Sikh Guru's writings that was compiled by the 5th Sikh Guru). It is the fifth-largest organized religion in the world, with approximately 30 million adherents.[2][3] Punjab, India is the only state in the world with a majority Sikh population.

Adherents of Sikhism are known as Sikhs (students or disciples). According to Devinder Singh Chahal, "The word 'Sikhi' (commonly known as Gurmat) gave rise to the modern anglicized word 'Sikhism' for the modern world."[4] Gurmat means literally 'wisdom of the Guru' in contrast to Manmat, or self-willed impulses.[5]

According to Sewa Singh Kalsi, "The central teaching in Sikhism is the belief in the concept of the oneness of God."[6] Sikhism considers spiritual life and secular life to be intertwined.[7] Guru Nanak, the first Sikh Guru established the system of the Langar, or communal kitchen, in order to demonstrate the need to share and have equality between all people.[8] Sikhs also believe that "all religious traditions are equally valid and capable of enlightening their followers".[6] In addition to sharing with others Guru Nanak inspired people to earn an honest living without exploitation and also the need for remembrance of the divine name (God). Guru Nanak described living an "active, creative, and practical life" of "truthfulness, fidelity, self-control and purity" as being higher than a purely contemplative life.[9] Guru Hargobind, the sixth Sikh Guru, established the political/temporal (Miri) and spiritual (Piri) realms to be mutually coexistent.[10]

According to the ninth Sikh Guru, Tegh Bahadhur, the ideal Sikh should have both Shakti (power that resides in the temporal), and Bhakti (spiritual meditative qualities). Finally the concept of the baptized Saint Soldier of the Khalsa was formed by the tenth Sikh Guru, Gobind Singh in 1699 at Anandpur Sahib.[11] Sikhs are expected to embody the qualities of a "Sant-Sipāhī"—a saint-soldier.[12][13] Sikhs are expected to have control over the so-called "Five Thieves" dispel these by means of the so-called "Five Virtues".

Philosophy and teachings

The origins of Sikhism lie in the teachings of Guru Nanak and his successors. The essence of Sikh teaching is summed up by Guru Nanak in these words: "Realization of Truth is higher than all else. Higher still is truthful living".[14] Sikh teaching emphasizes the principle of equality of all humans and rejects discrimination on the basis of caste, creed, and gender. Sikh principles encourage living life as a householder.

Sikhism is a monotheistic[15][16] and a revealed religion.[17] In Sikhism, God—termed Vāhigurū—is shapeless, timeless, and sightless (i.e., unable to be seen with the physical eye): niraṅkār, akaal, and alakh. The beginning of the first composition of Sikh scripture is the figure "1"—signifying the universality of God. It states that God is omnipresent and infinite with power over everything, and is signified by the term Ik Onkar.[18] Sikhs believe that before creation, all that existed was God and God's hukam (will or order).[19] When God willed, the entire cosmos was created. From these beginnings, God nurtured "enticement and attachment" to māyā, or the human perception of reality.[20]

The Sikh Concept of God

Sikhism advocates the belief in one panentheistic God (Ek Onkar) who is omnipresent and has infinite qualities. Sikhs do not have a gender for God nor do they believe God takes a human form. All human beings are considered equal regardless of their religion, sex or race. All are sons and daughters of Waheguru, the Almighty. "[21]"

Liberation

Guru Nanak's teachings are founded not on a final destination of heaven or hell but on a spiritual union with the Akal which results in salvation or Jivanmukta,[22] Guru Gobind Singh makes it clear that human birth is obtained with great fortune, therefore one needs to be able to make the most of this life.[23] There has been some confusion among scholars, interpreting the pertinent religious texts as evidence that Sikhs believe in reincarnation and karma as the same as Hinduism and Buddhism when such is not the case.[23][24][25] In Sikhism karma "is modified by the concept of God's grace" (nadar, mehar, kirpa, karam etc). Guru Nanak states "The body takes birth because of karma, but salvation is attained through grace".[26] To get closer to God: Sikhs avoid the evils of Maya, keep the everlasting truth in mind, practice Shabad Kirtan, meditate on Naam, and serve humanity. Sikhs believe that being in the company of the Satsang or Sadh Sangat is one of the key ways to achieve liberation from the cycles of reincarnation.[27]

Worldly Illusion

Māyā—defined as a temporary illusion or "unreality"—is one of the core deviations from the pursuit of God and salvation: where worldly attractions which give only illusory temporary satisfaction and pain which distract the process of the devotion of God. However, Nanak emphasised māyā as not a reference to the unreality of the world, but of its values. In Sikhism, the influences of ego, anger, greed, attachment, and lust—known as the Five Thieves—are believed to be particularly distracting and hurtful. Sikhs believe the world is currently in a state of Kali Yuga (Age of Darkness) because the world is lead astray by the love of and attachment to Maya.[28] The fate of people vulnerable to the Five Thieves ('Pānj Chor'), is separation from God, and the situation may be remedied only after intensive and relentless devotion.[29]

The Timeless Truth

According to Nanak the supreme purpose of human life is to reconnect with Akal (The Timeless One), however, egotism is the biggest barrier in doing this. Using the Guru's teaching remembrance of nām (the divine Word or the Name of the Lord)[30][31] leads to the end of egotism. Guru Nanak designated the word 'guru' (meaning teacher) to mean the voice of God: the source of knowledge and the guide to salvation.[32] As Ik Onkar is universally immanent, guru is indistinguishable from God and are one and the same.[33] One connects with guru only with accumulation of selfless search of truth.[34] Ultimately the seeker realizes that it is the consciousness within the body which is seeker/follower and the Word is the true guru. The human body is just a means to achieve the reunion with Truth.[33] Once truth starts to shine in a person’s heart, the essence of current and past holy books of all religions is understood by the person.[35]

Singing and Music

Sikhs refer to the hymns of the Gurus as Gurbani (The Guru's word).Shabad Kirtan is the singing of Gurbani. The entire Guru Granth Sahib is written in a form of poetry and rhyme. Guru Nanak started the Shabad Kirtan tradition and taught that listening to kirtan is a powerful way to achieve tranquility while meditating; Singing of the glories of the Supreme Timeless One (God) with devotion is the most effective way to come in communion with the Supreme Timeless One.[36] The three morning prayers for Sikhs consist of Japji Sahib, Jaap Sahib and Tav-Prasad Savaiye.[37] Baptized Sikhs rise early and meditate and then recite all the Five Banis of Nitnem before breakfast.

Remembrance

A key practice by Sikhs is remembrance[31] of the Divine Name (Naam – the Name of the Lord).[30] This contemplation is done through Nām Japna (repetition of the divine name) or Naam Simran (remembrance of the divine Name through recitation).[31][38] The verbal repetition of the name of God or a sacred syllable is an established practice in religious traditions in India but Guru Nanak's interpretation emphasized inward, personal observance. Guru Nanak's ideal is the total exposure of one's being to the divine Name and a total conforming to Dharma or the "Divine Order". Nanak described the result of the disciplined application of nām simraṇ as a "growing towards and into God" through a gradual process of five stages. The last of these is sach khaṇḍ (The Realm of Truth)—the final union of the spirit with God.[32]

Service and Action

Meditation is unfruitful without service and action.[39] Sikhs are taught that selfless service, or sēvā, and charitable work enables the devotee to kill the ego.[40] Service in Sikhism takes three forms: "Tan" - physical service; "Man" - mental service (such as studying to help others); and "Dhan" - material service.[41] Guru Nanak stressed now kirat karō: that a Sikh should balance work, worship, and charity, and should defend the rights of all human beings. They are encouraged to have a chaṛdī kalā, or optimistic - resilience, view of life. Sikh teachings also stress the concept of sharing—vaṇḍ chakkō—through the distribution of free food at Sikh gurdwaras (laṅgar), giving charitable donations, and working for the good of the community and others (sēvā).

Justice and Equality

Sikhism regards "Justice"[42] and "Restorative Justice" and "divine justice"[42] as trumping any subjective codes of moral order.[12][13][42][43] The word in Punjabi used to depict this is "Niau"[42] which means justice. The word "dharam" (righteousness)[42] is also used to convey justice "in the sense of the moral order".[42][44] "An attack on dharam is an attack on justice, on righteousness, and on the moral order generally".[5] According to the Tenth Sikh Guru, Guru Gobind Singh "when all efforts to restore peace prove useless and no words avail, lawful is the flash of steel, it is right to draw the sword".[45]

Men and women are equal in Sikhism and share the same rights.It should be noted, while churches have been arguing, in recent times on female priest ordination, women have been leading in prayers at Sikh temples since the foundation of Sikhism(some 500 years).[46]

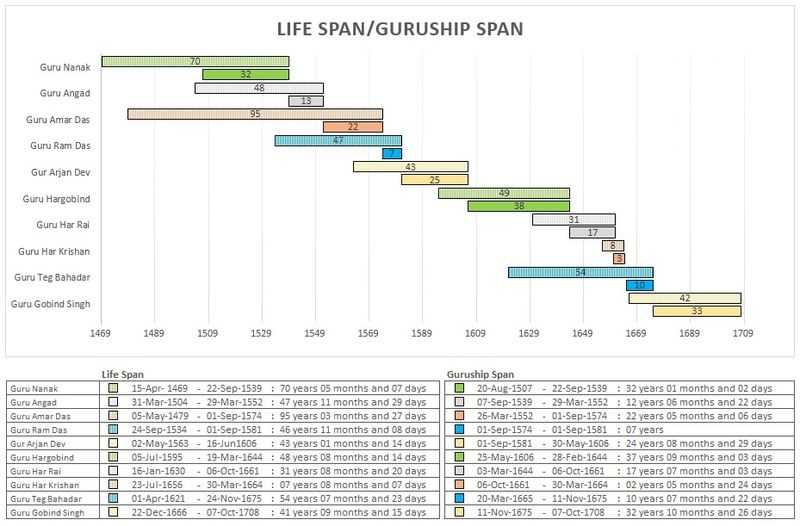

Ten gurus and religious authority

The term guru comes from the Sanskrit gurū, meaning teacher, guide, or mentor. The traditions and philosophy of Sikhism were established by ten specific gurus from 1469 to 1708. Each guru added to and reinforced the message taught by the previous, resulting in the creation of the Sikh religion. Guru Nanak was the first guru and appointed a disciple as successor. Guru Gobind Singh was the final guru in human form. Before his death, Guru Gobind Singh decreed that the Gurū Granth Sāhib would be the final and perpetual guru of the Sikhs.[47] Guru Angad succeeded Guru Nanak. Later, an important phase in the development of Sikhism came with the third successor, Guru Amar Das. Guru Nanak's teachings emphasised the pursuit of salvation; Guru Amar Das began building a cohesive community of followers with initiatives such as sanctioning distinctive ceremonies for birth, marriage, and death. Amar Das also established the manji (comparable to a diocese) system of clerical supervision.[32]

Guru Amar Das's successor and son-in-law Guru Ram Das founded the city of Amritsar, which is home of the Harimandir Sahib and regarded widely as the holiest city for all Sikhs. Guru Arjan was captured by Mughal authorities who were suspicious and hostile to the religious order he was developing.[48] His persecution and death inspired his successors to promote a military and political organization of Sikh communities to defend themselves against the attacks of Mughal forces.

History

Guru Nanak (1469–1539), the founder of Sikhism, was born in the village of Rāi Bhōi dī Talwandī, now called Nankana Sahib (in present-day Pakistan).[50] His parents were Khatri Hindus. As a boy, Nanak was fascinated by God and religion. He would not partake in religious rituals or customs and oddly meditated alone. His desire to explore the mysteries of life eventually led him to leave home and take missionary journeys.

In his early teens, Nanak caught the attention of the local landlord Rai Bular Bhatti, who was moved by his amazing intellect and divine qualities. Rai Bular Bhatti was witness to many incidents in which Nanak enchanted him and as a result Rai Bular Bhatti and Nanak's sister Bibi Nanki, became the first persons to recognise the divine qualities in Nanak. Both of them then encouraged and supported Nanak to study and travel. At the age of thirty, Nanak went missing and was presumed to have drowned after going for one of his morning baths to a local stream called the Kali Bein. He reappeared three days later and declared: "There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim" (in Punjabi, "nā kōi hindū nā kōi musalmān"). It was from this moment that Nanak would begin to spread the teachings of what was then the beginning of Sikhism.[51] Although the exact account of his itinerary is disputed, he is widely acknowledged to have made five major journeys, spanning thousands of miles, the first tour being east towards Bengal and Assam, the second south towards Andhra and Tamil Nadu, the third north towards Kashmir, Ladakh, and Tibet, and the fourth tour west towards Baghdad and Mecca.[52] In his last and final tour, he returned to the banks of the Ravi River to end his days.[53]

Growth of Sikhism

In 1539, Guru Nanak chose his disciple Lahiṇā as a successor to the guruship rather than either of his sons. Lahiṇā was named Guru Angad and became the second guru of the Sikhs.[54] Nanak conferred his choice at the town of Kartarpur on the banks of the river Ravi, where Nanak had finally settled down after his travels. Though Sri Chand was not an ambitious man, the Udasis believed that the Guruship should have gone to him, since he was a man of pious habits in addition to being Nanak's son. On Nanak's advice, Guru Angad shifted from Kartarpur to Khadur, where his wife Khivi and children were living, until he was able to bridge the divide between his followers and the Udasis. Guru Angad continued the work started by Guru Nanak and is widely credited for standardising the Gurmukhī script as used in the sacred scripture of the Sikhs.

Guru Amar Das became the third Sikh guru in 1552 at the age of 73. Goindval became an important centre for Sikhism during the guruship of Guru Amar Das. He preached the principle of equality for women by prohibiting purdah and sati. Guru Amar Das also encouraged the practice of langar and made all those who visited him attend laṅgar before they could speak to him.[55] In 1567, Emperor Akbar sat with the ordinary and poor people of Punjab to have laṅgar. Guru Amar Das also trained 146 apostles of which 52 were women, to manage the rapid expansion of the religion.[56] Before he died in 1574 aged 95, he appointed his son-in-law Jēṭhā, a Khatri of the Sodhi clan, as the fourth Sikh guru.

Jēṭhā became Guru Ram Das and vigorously undertook his duties as the new guru. He is responsible for the establishment of the city of Ramdaspur later to be named Amritsar. Before Ramdaspur, Amritsar was known as Guru Da Chakk. In 1581, Guru Arjan—youngest son of the fourth guru—became the fifth guru of the Sikhs. In addition to being responsible for building the Harimandir Sahib, he prepared the Sikh sacred text known as the Ādi Granth (literally the first book) and included the writings of the first five gurus and other enlightened Hindu and Muslim saints. In 1606 he was tortured and killed by the Mughal Emperor, Jahangir[57] for refusing to make changes to the Granth and for supporting an unsuccessful contender to the throne.

Political advancement

Guru Hargobind, became the sixth guru of the Sikhs. He carried two swords—one for spiritual and the other for temporal reasons (known as mīrī and pīrī in Sikhism).[58] Sikhs grew as an organized community and under the 10th Guru the Sikhs developed a trained fighting force to defend their independence. In 1644, Guru Har Rai became guru followed by Guru Har Krishan, the boy guru, in 1661. Guru Har Krishan helped to heal many sick people. Coming into contact with so many people every day, he too was infected and taken seriously ill and later died. No hymns composed by these three gurus are included in the Guru Granth Sahib.[59]

Guru Tegh Bahadur became guru in 1665 and led the Sikhs until 1675. Guru Tegh Bahadur was executed by Aurangzeb for helping to protect the faith of Hindus, after a delegation of Kashmiri Pandits came to him for help when the Emperor was killing those who refused to convert to Islam.[60] He was succeeded by his son, Gobind Rai who was just nine years old at the time of his father's death. Gobind Rai further militarised his followers, and was baptised by the Pañj Piārē when he formed the Khalsa on 30 March 1699. From here on in he was known as Guru Gobind Singh.

From the time of Nanak the Sikhs had significantly transformed. Even though the core Sikh spiritual philosophy was never affected, the followers now began to develop a political identity. Conflict with Mughal authorities escalated during the lifetime of Guru Teg Bahadur and Guru Gobind Singh.

Sikh Confederacy and the rise of the Khalsa

The tenth guru of Sikhism, Guru Gobind Singh, founded the Khalsa (the collective body of all initiated Sikhs) as the Sikh temporal authority in the year 1699.[61] The Khalsa is a disciplined community that combines its spiritual purpose and goals with political and military duties.[47][62] Shortly before his death, Guru Gobind Singh proclaimed the Gurū Granth Sāhib (the Sikh Holy Scripture) to be the ultimate spiritual authority for the Sikhs.[63]

The Sikh Khalsa's rise to power began in the 17th century during a time of growing militancy against Mughal rule. The creation of a Sikh Empire began when Guru Gobind Singh sent a Sikh general, Banda Singh Bahadur, to fight the Mughal rulers of India[64] and those who had committed atrocities against Pir Buddhu Shah. Banda Singh advanced his army towards the main Muslim Mughal city of Sirhind and, following the instructions of the guru, punished all the culprits. Soon after the invasion of Sirhind, while resting in his chamber after the Rehras prayer Guru Gobind Singh was stabbed by a Pathan assassin hired by Mughals. Gobind Singh killed the attacker with his sword. Though a European surgeon stitched the Guru's wound, the wound re-opened as the Guru tugged at a hard strong bow after a few days, causing profuse bleeding that led to Gobind Singh's death.

After the Guru's death, Baba Banda Singh Bahadur became the commander-in-chief of the Khalsa.[65] He organized the civilian rebellion and abolished or halted the Zamindari system in time he was active and gave the farmers proprietorship of their own land.[66] Banda Singh was executed by the emperor Farrukh Siyar after refusing the offer of a pardon if he converted to Islam. The confederacy of Sikh warrior bands known as misls alongside the development of the Dal Khalsa achieved a series of sweeping military and diplomatic victories, eventually creating a Sikh Empire in the Punjab under the emperor, Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1799. The vast Sikh empire with its capital in Lahore and limits reaching the Khyber Pass and the borders of China comprised almost 200,000 square miles (520,000 square kilometres) of what is now Afghanistan, Pakistan and Northern India. The Sikh nation's embrace of military and political organisation made it a considerable regional force in 19th century India and allowed it to retain control of the Sikh Empire in the face of numerous local uprisings.[67] The order, traditions and discipline developed over centuries culminated at the time of Ranjit Singh to give rise to a common religious and social identity.[68]

After the death of Ranjit Singh in 1839, the Sikh Empire fell into disorder and, after the assassination of several successors, eventually fell on the shoulders of his youngest son, Maharaja Duleep Singh. Soon after, the British began to attack the Sikh Kingdom. Both British and Sikh sides sustained heavy losses of both troops and materials in the hard-fought First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars. The Empire was eventually annexed by the United Kingdom, bringing the Punjab under the British Raj.

A quarter of a century later, Sikhs formed the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee and the Shiromani Akali Dal to preserve Sikhs' religious and political organization. With the partition of India in 1947, thousands of Sikhs were killed in violence and millions were forced to leave their ancestral homes in West Punjab.[69] Sikhs faced initial opposition from the Government in forming a linguistic state that other states in India were afforded. The Akali Dal started a non-violence movement for Sikh and Punjabi rights. Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale emerged as a leader of the Damdami Taksal in 1977 and promoted a more militant solution to the problem. In June 1984, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered the Indian army to launch Operation Blue Star to remove Bhindranwale and his followers from the Darbar Sahib. Bhindranwale and his accompanying followers, as well as many innocent Sikhs visiting the temple, were killed during the army's operations. In October, Indira Gandhi was assassinated by two of her Sikh bodyguards. The assassination was followed by the 1984 anti-Sikh riots.[70] and Hindu-Sikh conflicts in Punjab, as a reaction to Operation Blue Star and the assassination..

Scripture

There is one primary source of scripture for the Sikhs: the Gurū Granth Sāhib. The Gurū Granth Sāhib may be referred to as the Ādi Granth—literally, The First Volume—and the two terms are often used synonymously. Here, however, the Ādi Granth refers to the version of the scripture created by Guru Arjan in 1604. The Gurū Granth Sāhib is the final version of the scripture created by Guru Gobind Singh.

There are other sources of scriptures such as the Dasam Granth and so called Janamsakhis. These however, have been the subject of controversial debate amongst the Sikh community.

Adi Granth

The Ādi Granth was compiled primarily by Bhai Gurdas under the supervision of Guru Arjan between the years 1603 and 1604.[71] It is written in the Gurmukhī script, which is a descendant of the Laṇḍā script used in the Punjab at that time.[72] The Gurmukhī script was standardised by Guru Angad, the second guru of the Sikhs, for use in the Sikh scriptures and is thought to have been influenced by the Śāradā and Devanāgarī scripts. An authoritative scripture was created to protect the integrity of hymns and teachings of the Sikh gurus and fifteen bhagats. These fifteen bhagats are Namdev, Ravidas, Jaidev, Trilocan, Beni, Ramanand, Sainu, Dhanna, Sadhna, Pipa, Sur, Bhikhan, Paramanand, Farid, and Kabir.[73] At the time, Arjan Sahib tried to prevent undue influence from the followers of Prithi Chand, the guru's older brother and rival.[74]

Guru Granth Sahib

The final version of the Gurū Granth Sāhib was compiled by Guru Gobind Singh in 1678. It consists of the original Ādi Granth with the addition of Guru Tegh Bahadur's hymns. The Guru Granth Sahib is considered the Eleventh and final spiritual authority of the Sikhs.

- Punjabi: ਸੱਬ ਸਿੱਖਣ ਕੋ ਹੁਕਮ ਹੈ ਗੁਰੂ ਮਾਨਯੋ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ।

- Transliteration: Sabb sikkhaṇ kō hukam hai gurū mānyō granth.

- English: All Sikhs are commanded to take the Granth as Guru.

It contains compositions by the first five Gurus, Guru Teg Bahadur and just one śalōk (couplet) from Guru Gobind Singh.[75] It also contains the traditions and teachings of sants (saints) such as Kabir, Namdev, Ravidas, and Sheikh Farid along with several others.[68]

The bulk of the scripture is classified into rāgs, with each rāg subdivided according to length and author. There are 31 rāgs within the Gurū Granth Sāhib. In addition to the rāgs, there are clear references to the folk music of Punjab. The main language used in the scripture is known as Sant Bhāṣā, a language related to both Punjabi and Hindi and used extensively across medieval northern India by proponents of popular devotional religion.[62] As per the name "Gurmukhi", it is not merely a script but it is the language which came out of Guru's mouth – by using this definition, all words in Guru Granth Sahib constitute "Gurbani" words, thus making Gurmukhi language which then constitute two components – spoken Gurmukhi words (in form of Gurbani which originated from different languages (like world's different languages have similar roots) and Gurmukhi script. The text further comprises over 5000 śabads, or hymns, which are poetically constructed and set to classical form of music rendition, can be set to predetermined musical tāl, or rhythmic beats.

The Granth begins with the Mūl Mantra, an iconic verse created by Nanak:

- Punjabi: ੴ ਸਤਿ ਨਾਮੁ ਕਰਤਾ ਪੁਰਖੁ ਨਿਰਭਉ ਨਿਰਵੈਰੁ ਅਕਾਲ ਮੂਰਤਿ ਅਜੂਨੀ ਸੈਭੰ ਗੁਰ ਪ੍ਰਸਾਦਿ ॥

- ISO 15919 transliteration: Ika ōaṅkāra sati nāmu karatā purakhu nirabha'u niravairu akāla mūrati ajūnī saibhaṅ gura prasādi.

- Simplified transliteration: Ik ōaṅgkār sat nām kartā purkh nirbha'u nirvair akāl mūrat ajūnī saibhaṅ gur prasād.

- English: The One of which everything is and continuous, the ever existing, creator being personified, without fear, without hatred, image Of the timeless being, beyond birth, self existent, by Guru's Grace.

All text within the Granth is known as gurbānī. And Gurbani is the Guru "Baani Guru Guru hai Baani" (The word is the Guru and Guru is the word) and "Shabd Guru Surat Dhun Chaylaa" (The Shabad is the Guru, upon whom I lovingly focus my consciousness; I am the disciple.). Therefore, as evident from the message of the Guru Nanak (first Guru) Shabad (or word) was always the Guru (the enlightener); however, as Sikhism stand on the dual strands of Miri-Piri, the Guru in Sikhism is a combination of teacher-leader. Therefore, the lineage from Guru Nanak to Guru Gobind Singh was of the teacher-leaders eventually wherein the temporal authority was passed on to the Khalsa and spiritual authority, which always was with, passed to Adi Granth(thence the Guru Granth Sahib).

Therefore, Guru Granth Sahib and its 11th body -the Khalsa is the Guru, teacher-leader, of the Sikhs till eternity.

Dasam Granth

The Dasam Granth is a scripture of Sikhs which contains texts attributed to the Tenth Guru. The Dasam Granth holds a significance of great amount for Sikhs, however it does not have the same authority as Adi Granth. Some compositions of the Dasam Granth like Jaap Sahib, (Amrit Savaiye), and Benti Chaupai are part of the daily prayers/lessons (Nitnem) of/for Sikhs.

The authenticity of the Dasam Granth is amongst the most debated topics within Sikhism.

Janamsakhis

The Janamsākhīs (literally birth stories), are writings which profess to be biographies of Nanak. Although not scripture in the strictest sense, they provide an interesting look at Nanak's life and the early start of Sikhism. There are several—often contradictory and sometimes unreliable—Janamsākhīs and they are not held in the same regard as other sources of scriptural knowledge.

Observances

Observant Sikhs adhere to long-standing practices and traditions to strengthen and express their faith. The daily recitation from memory of specific passages from the Gurū Granth Sāhib, especially the Japu (or Japjī, literally chant) hymns is recommended immediately after rising and bathing. Family customs include both reading passages from the scripture and attending the gurdwara (also gurduārā, meaning the doorway to God; sometimes transliterated as gurudwara). There are many gurdwaras prominently constructed and maintained across India, as well as in almost every nation where Sikhs reside. Gurdwaras are open to all, regardless of religion, background, caste, or race.

Worship in a gurdwara consists chiefly of singing of passages from the scripture. Sikhs will commonly enter the gurdwara, touch the ground before the holy scripture with their foreheads. The recitation of the eighteenth century ardās is also customary for attending Sikhs. The ardās recalls past sufferings and glories of the community, invoking divine grace for all humanity.[76]

The Sikh faith also participates in the custom of "Langar" or the community meal. All gurdwaras are open to anyone of any faith for a free meal. People can enter and eat together and are served by faithful members of the community. This is the main cost associated with gurdwaras and where monetary donations are primarily spent.

Sikh festivals/events

Technically, there are no festivals in Sikhism. However, the events mostly centred around the lives of the Gurus and Sikh martyrs are commemorated. The SGPC, the Sikh organisation in charge of upkeep of the historical gurdwaras of Punjab, organises celebrations based on the new Nanakshahi calendar. This calendar is highly controversial among Sikhs and is not universally accepted. Sikh festivals include the following:

- Gurpurabs are celebrations or commemorations based on the lives of the Sikh gurus. They tend to be either birthdays or celebrations of Sikh martyrdom. All ten Gurus have Gurpurabs on the Nanakshahi calendar, but it is Guru Nanak Dev and Guru Gobind Singh who have a gurpurab that is widely celebrated in Gurdwaras and Sikh homes. The martyrdoms are also known as a shaheedi Gurpurabs, which mark the martyrdom anniversary of Guru Arjan Dev and Guru Tegh Bahadur. Since 2011 the Gurpurab of Guru Har Rai Sahib (March 14) has been celebrated as Sikh Vatavaran Diswas (Sikh Environment Day). Guru Har Rai was the seventh guru, known as a gentle guru man who cared for animals and the environment. The day is marked by worldwide events, including tree plantings, rubbish clearances and celebrations of the natural world.[77]

- Nagar Kirtan involves the processional singing of holy hymns throughout a community. While practiced at any time, it is customary in the month of Visakhi (or Vaisakhi). Traditionally, the procession is led by the saffron-robed Panj Piare (the five beloved of the Guru), who are followed by the Guru Granth Sahib, the holy Sikh scripture, which is placed on a float.

- Visakhi which includes Parades and Nagar Kirtan occurs on 13 April. Sikhs celebrate it because on this day which fell on 30 March 1699, the tenth Guru, Gobind Singh, inaugurated the Khalsa, the 11th body of Guru Granth Sahib and leader of Sikhs till eternity.

- Bandi Chhor celebrates Guru Hargobind's release from the Gwalior Fort, with several innocent Hindu kings who were also imprisoned by Jahangir, on 26 October 1619. This day usually commemorated on the same day of Hindu festival of Diwali.

- Hola Mohalla occurs the day after Holi and is when the Khalsa gather at Anandpur and display their individual and team warrior skills, including fighting and riding.

Ceremonies and customs

Guru Nanak taught that rituals, religious ceremonies, or idol worship are of little use and Sikhs are discouraged from fasting or going on pilgrimages.[78] Sikhs do not believe in converting people but converts to Sikhism by choice are welcomed. The morning and evening prayers take around two hours a day, starting in the very early morning hours. The first morning prayer is Guru Nanak's Jap Ji. Jap, meaning "recitation", refers to the use of sound, as the best way of approaching the divine. Like combing hair, hearing and reciting the sacred word is used as a way to comb all negative thoughts out of the mind. The second morning prayer is Guru Gobind Singh's universal Jaap Sahib. The Guru addresses God as having no form, no country, and no religion but as the seed of seeds, sun of suns, and the song of songs. The Jaap Sahib asserts that God is the cause of conflict as well as peace, and of destruction as well as creation. Devotees learn that there is nothing outside of God's presence, nothing outside of God's control. Devout Sikhs are encouraged to begin the day with private meditations on the name of God.

Upon a child's birth, the Guru Granth Sahib is opened at a random point and the child is named using the first letter on the top left hand corner of the left page. All boys are given the last name Singh, and all girls are given the last name Kaur (this was once a title which was conferred on an individual upon joining the Khalsa).[79] Sikhs are joined in wedlock through the anand kāraj ceremony. Sikhs are required to marry when they are of a sufficient age (child marriage is taboo), and without regard for the future spouse's caste or descent. The marriage ceremony is performed in the company of the Guru Granth Sahib; around which the couple circles four times. After the ceremony is complete, the husband and wife are considered "a single soul in two bodies."[80]

According to Sikh religious rites, neither husband nor wife is permitted to divorce unless special circumstances arise. A Sikh couple that wishes to divorce may be able to do so in a civil court.[81] Upon death, the body of a Sikh is usually cremated. If this is not possible, any means of disposing the body may be employed. The kīrtan sōhilā and ardās prayers are performed during the funeral ceremony (known as antim sanskār).[82]

Baptism and the Khalsa

Khalsa (meaning "Sovereign") is the collective name given by Gobind Singh to all Sikhs, male or female, who have been baptised or initiated by taking ammrit in a ceremony called ammrit sañcār. The first time that this ceremony took place was on Vaisakhi, which fell on 30 March 1699 at Anandpur Sahib in Punjab. It was on that occasion that Gobind Singh baptised the Pañj Piārē—the five beloved ones, who in turn baptised Gobind Singh himself. The last name, Singh, meaning lion, is given to baptized Sikh males, and the last name Kaur, meaning princess/lioness, is given to baptized Sikh females. Baptised Sikhs are bound to wear the Five Ks (in Punjabi known as pañj kakkē or pañj kakār), or articles of faith, at all times. The 5 items are: kēs (uncut hair), kaṅghā (small wooden comb), kaṛā (circular steel or iron bracelet), kirpān (sword/dagger), and kacchera (special undergarment). The Five Ks have both practical and symbolic purposes.[83]

Sikh people

Worldwide, there are 25.8 million Sikhs, which makes up 0.39% of the world's population. Approximately 75% of Sikhs live in the Punjab, where they constitute about 60% of the state's population. Large communities of Sikhs live in the neighboring states such as Indian State of Haryana which is home to the second largest Sikh population in India with 1.1 million Sikhs as per 2001 census, and large communities of Sikhs can be found across India. However, Sikhs only comprise about 2% of the Indian population.[84]

Sikh migration beginning from the 19th century led to the creation of significant communities in Canada (predominantly in Brampton, along with British Columbia), East Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, the United Kingdom as well as United States and Australia. These communities developed as Sikhs migrated out of Punjab to fill in gaps in imperial labour markets.[85] In the early twentieth century a significant community began to take shape on the west coast of the United States. Smaller populations of Sikhs are found in within many countries in Western Europe, Mauritius, Malaysia, Fiji, Nepal, China, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Singapore, Mexico, the United States and many other countries.

According to Sewa Singh Kalsi, the Sikh people have gained a reputation through history for beingsturdy, hardworking and adventurous; they are a people who have earned the reputation for beinbg extremely brace and loyal soldiers. They have also become known for being a militant people.[84]

Beginning in 1968, Yogi Bhajan (later of the 3HO movement) began to teach classes kundalini yoga, resulting in a number of non-Punjabi converts to Sikhism (known as white Sikhs) in the United States. Since then, thousands of non-Punjabis have taken up the Sikh belief and lifestyle primarily in the United States, Canada, Latin America, the Far East and Australia.[86]

Since 2010, the Sikh Directory has organized The Sikh Awards, the first Sikh award ceremony in the world.[87]

Prohibitions in Sikhism

There are a number of religious prohibitions in Sikhism.

Prohibited are:

- Cutting hair: Cutting hair is strictly forbidden in Sikhism for those who have taken the Amrit initiation ceremony.These Amritdhari or Khalsa Sikhs are required to keep unshorn hair.

- Intoxication: Consumption of alcohol, drugs, tobacco, and other intoxicants is not allowed. Intoxicants are strictly forbidden for a Sikh.[88][89][90] However the Nihangs of Punjab take an infusion of cannabis to assist meditation.[91]

- Blind spirituality: Superstitions and rituals should not be observed or followed, including pilgrimages, fasting and ritual purification; circumcision; idols & grave worship; compulsory wearing of the veil for women; etc.

- Material obsession: Obsession with material wealth is not encouraged in Sikhism.

- Sacrifice of creatures: The practice of sati (widows throwing themselves on the funeral pyre of their husbands), ritual animal sacrifice to celebrate holy occasions, etc. are forbidden.

- Non-family-oriented living: A Sikh is encouraged not to live as a recluse, beggar, yogi, monastic (monk/nun) or celibate. Sikhs are to live as saint-soldiers.

- Worthless talk: Bragging, lying, slander, "back-stabbing", etc. are not permitted. The Guru Granth Sahib tells the Sikh, "Your mouth has not stopped slandering and gossiping about others. Your service is useless and fruitless."[92]

- Priestly class: Sikhism does not have priests; they were abolished by Guru Gobind Singh (the 10th Guru of Sikhism).[93] The only position he left was a Granthi to look after the Guru Granth Sahib, any Sikh is free to become Granthi or read from the Guru Granth Sahib.[93]

- Eating meat killed in a ritualistic manner (Kutha meat): Sikhs are strictly prohibited from eating meat from animals slaughtered in a religiously prescribed manner (such as dhabihah or shechita, known as Kutha meat, when the animal is killed by exsanguination via throat-cutting),[94] or any meat where langar is served.[95] The meat eaten by Sikhs is known as Jhatka meat.[96][97]

- Having extramarital sexual relations.[88][89][98][99]

See also

|

- Indian religions

- Interfaith dialog

- Khalsa

- Outline of Sikhism

- Sikh

Notes

References

- ↑ Singh, Patwant; (2000). The Sikhs. Alfred A Knopf Publishing. Pages 17. ISBN 0-375-40728-6.

- ↑ "Sikhism: What do you know about it?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Zepps, Josh. "Sikhs in America: What You Need To Know About The World's Fifth-Largest Religion". Huffington Post. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Chahal, Devinder (July–December 2006). "Understanding Sikhism in the Science Age". Understanding Sikhism, The Research Journal (2): 3. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Mcleod, WH (19 July 1984). Sikhism (Textual Sources for the Study of Religion). Manchester University Press. p. 138. ISBN 0719010632.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Singh Kalsi, Sewa (2007). Sikhism. London: Bravo Ltd. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-85733-436-4.

- ↑ Nayar, Kamal Elizabeth and Sandhu, Jaswinder Singh (2007). 's&hl=en&sa=X&ei=WWL_UdChAYG3O4jbgfgO&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=The%20Socially%20Involved%20Renunciate%20-%20Guru%20Nanaks%20Discourse%20to%20Nath%20Yogi's&f=false "Chapter Six - Renunciation and Social Involvement in Siddhe Gost". The Socially Involved Renunciate - Guru Nanaks Discourse to Nath Yogi's. United States of America: State University of New York Press. p. 106.

- ↑ Thaker, Aruna (2012). Multicultural Handbook of Food, Nutrition and Dietetics. John Wiley & Sons. p. 31. ISBN 9781118350461.

- ↑ Marwha, Sonali Bhatt (2006). Colors of Truth, Religion Self and Emotions. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. p. 205. ISBN 818069268X.

- ↑ E. Marty, Martin and Appleby R. Scott (11 July 1996). Fundamentalisms and the State: Remaking Polities, Economies, and Militance. University of Chicago Press. p. 278. ISBN 0226508846.

- ↑ Singh Gandhi, Surjit (1 Feb 2008). History of Sikh Gurus Retold: 1606 -1708. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors Pvt Ltd. pp. 676–677. ISBN 8126908572.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Chanchreek, Jain (2007). Encyclopaedia of Great Festivals. Shree Publishers & Distributors. p. 142. ISBN 9788183291910.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Dugga, Kartar (2001). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: The Last to Lay Arms. Abhinav Publications. p. 33. ISBN 9788170174103.

- ↑ Teece, Geoff (2004). Sikhism:Religion in focus. Black Rabbit Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-58340-469-0.

- ↑ Mark Juergensmeyer, Gurinder Singh Mann (2006). The Oxford Handbook of Global Religions. US: Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-19-513798-9.

- ↑ Ardinger, Barbara (2006). Pagan Every Day: Finding the Extraordinary in Our Ordinary Lives. Weisfer. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-57863-332-6.

- ↑ Nesbitt, Eleanor M. (15 November 2005). Sikhism: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-19-280601-7. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ↑ Parrinder, Geoffrey (1971). World Religions:From Ancient History to the Present. USA: Hamlyn Publishing Group. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-87196-129-7.

- ↑ Dev, Guru Nanak Dev. Guru Granth Sāhib ji. p. 1035. Retrieved 15 June 2006. "For endless eons, there was only utter darkness. There was no earth or sky; there was only the

infiniteCommand of His Hukam." - ↑ Dev, Nanak. Gurū Granth Sāhib Ji. p. 1036. Retrieved 15 June 2006. "When He so willed, He created the world. Without any supporting power, He sustained the universe. He created Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva; He fostered enticement and attachment to Maya."

- ↑ Taoshobuddha (22 Aug 2012). Ek Onkar Satnam: The Heartbeat of Nanak. AuthorHouseUK. p. 438. ISBN 1477214267.

- ↑ Takhar, Opinderjit (2005). Sikh Identity: An Exploration Of Groups Among Sikhs. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 143. ISBN 9780754652021.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Chahal, Amarjit Singh (December 2011). "Concept of Reincarnation in Guru Nanak’s Philosophy". Understanding Sikhism – The Research Journal 13 (1-2): 52–59. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Philip (2008). Religions. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 209, 214–215. ISBN 978-0-7566-3348-6.

- ↑ House, H. Wayne (April 1991). "Resurrection, Reincarnation, and Humanness". Bibliotheca Sacra 148 (590). Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ Singh, H. S. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism. Hemkunt Press. p. 80. ISBN 9788170103011.

- ↑ Kapoor, Sukhbir (2005). Guru Granth Sahib - An Advance Study Volume-I. Hemkunt Press. p. 188. ISBN 9788170103172.

- ↑ Singh, Nirmal (2008). Searches In Sikhism. Hemkunt Press. p. 68. ISBN 9788170103677.

- ↑ Parrinder, Geoffrey (1971). World Religions: From Ancient History to the Present. United States: Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-87196-129-7.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Pruthi, Raj (2004). Sikhism and Indian Civilization. Discovery Publishing House. p. 204. ISBN 9788171418794.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 McLean, George (15 Jun 2008). Paths to The Divine: Ancient and Indian: 12. 1565182480: Council for Research in Values &. p. 599.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Parrinder, Geoffrey (1971). World Religions: From Ancient History to the Present. United States: Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-87196-129-7.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Singh, R.K. Janmeja (Meji) (August 2013). "Gurbani’s Guidance and the Sikh’s ‘Destination’". The Sikh Review. 8 61 (716): 27–35. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ Dhillon, Bikram Singh (January–June 1999). "Who is a Sikh? Definitions of Sikhism". Understanding Sikhism – The Research Journal 1 (1): 33–36, 27. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ Dhillon, Sukhraj Singh (May 2004). "Universality of the Sikh Philosophy: An Analysis". The Sikh Review. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ Singh, Joginder (2004). Celestial Gems. Hemkunt Press. p. 67. ISBN 9788170103455.

- ↑ Singh Bakhshi, Surinder (1 Sep 2008). "Chapter 22 - Nitnem". Sikhs in the Diaspora: A Modern Guide to the Practice of Sikh Faith. Sikh Publishing House; First edition. p. 133. ISBN 0956072801.

- ↑ Doel, Sarah (2008). Sikh Music: History, Text, and Praxis. ProQuest. p. 46. ISBN 9780549833697.

- ↑ Pamela Draycott, Alison Phillips, Cavan Wood (19 July 2005). "3.4 What Does Sikhism Teach About Poverty". In Janet Dyson, Ruth Mantin. Think RE: Pupil Book 2. Heinemann; 1 edition. p. 46. ISBN 0435307266.

- ↑ Singh, Harjeet (2009). Faith & Philosophy of Sikhism. Gyan Publishing House. p. 34. ISBN 9788178357218.

- ↑ Wood, Angela (1997). Movement and Change. Nelson Thornes. p. 46. ISBN 9780174370673.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 42.5 L. Hadley, Michael (8 Feb 2001). "Sikhism and Restorative Justice:Theory and Practice - Pashaura Singh". The Spiritual Roots of Restorative Justice (S U N Y Series in Religious Studies). State University of New York Press. p. 199. ISBN 0791448525.

- ↑ Brodd, Jeffrey (2009). World Religions: A Voyage of Discovery. Saint Mary's Press. p. 120. ISBN 9780884899976.

- ↑ Shiva, Vandana (1991). The Violence of Green Revolution: Third World Agriculture, Ecology and Politics. Zed Books. p. 188. ISBN 9780862329655.

- ↑ Marianne Fleming and David Worden (2 July 2004). "Sikhism". Religious Studies for AQA: Thinking About God and Morality (GCSE Religious Studies for AQA). Heinemann; 1 edition. p. 123. ISBN 0435307134.

- ↑ Rait, Satwant Kaur (2005). Sikh Women in England: Religious,Social and Cultural Beliefs. English: Trentham Books Ltd; illustrated edition edition. p. 51. ISBN 1858563534.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Mann, Gurinder Singh (2001). The Making of Sikh Scripture. United States: Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-19-513024-9.

- ↑ Parrinder, Geoffrey (1971). World Religions: From Ancient History to the Present. United States: Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-87196-129-7.

- ↑ "Sikh Reht Maryada — Method of Adopting Gurmatta". Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ↑ Singh, Khushwant (2006). The Illustrated History of the Sikhs. India: Oxford University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-19-567747-8. According to the Purātan Janamsākhī (the birth stories of Nanak)

- ↑ Shackle, Christopher; Mandair, Arvind-pal Singh (2005). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. United Kingdom: Routledge. xiii–xiv. ISBN 978-0-415-26604-8.

- ↑ Dr Harjinder Singh Dilgeer (2008). Sikh Twareekh. Belgium & India: The Sikh University Press.

- ↑ Finegan, Jack (1952). The Archeology of World Religions; the Background of Primitivism, Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Shinto, Islam, and Sikhism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Shackle, Christopher; Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2005). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. United Kingdom: Routledge. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-415-26604-8.

- ↑ Duggal, Kartar Singh (1988). Philosophy and Faith of Sikhism. Himalayan Institute Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-89389-109-1.

- ↑ Brar, Sandeep Singh (1998). "The Sikhism Homepage: Guru Amar Das". Retrieved 2006-05-26.

- ↑ Shackle, Christopher; Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2005). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. xv–xvi. ISBN 978-0-415-26604-8.

- ↑ Mahmood, Cynthia (2002). A Sea of Orange. United States: Xlibris. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4010-2856-5.

- ↑ Shackle, Christopher; Mandair, Arvind-pal Singh (2005). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. United Kingdom: Routledge. xvi. ISBN 978-0-415-26604-8.

- ↑ Rama, Swami (1986). Celestial Song/Gobind Geet: The Dramatic Dialogue Between Guru Gobind Singh and Banda Singh Bahadur. Himalayan Institute Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-89389-103-9.

- ↑ Shani, Giorgio (2008). Sikh Nationalism and Identity in a Global Age. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 9780415421904.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Parrinder, Geoffrey (1971). World Religions: From Ancient History to the Present. United States: Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-87196-129-7.

- ↑ Wolfe, Alvin (1996). Anthropological Contributions to Conflict Resolution. University of Georgia Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780820317656.

- ↑ Hansra, Harkirat (2007). Liberty at Stake. iUniverse. p. 67. ISBN 9780595875634.

- ↑ Indian Armed Forces Year Book. the University of California. 1959. p. 419.

- ↑ Jawandha, Nahar (2010). Glimpses of Sikhism. New Delhi: Sanbun Publishers. p. 81. ISBN 9789380213255.

- ↑ Singh, Khushwant (2006). The Illustrated History of the Sikhs. India: Oxford University Press. pp. 47–53. ISBN 978-0-19-567747-8.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Parrinder, Geoffrey (1971). World Religions: From Ancient History to the Present. United States: Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-87196-129-7.

- ↑ Pandey, Gyanendra (2001). Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-521-00250-9.

- ↑ Horowitz, Donald L. (2003). The Deadly Ethnic Riot. University of California Press. pp. 482–485. ISBN 978-0-520-23642-4.

- ↑ Trumpp, Ernest (2004) [1877]. The Ādi Granth or the Holy Scriptures of the Sikhs. India: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. p. 1xxxi. ISBN 978-81-215-0244-3.

- ↑ Grierson, George Abraham (1967) [1927]. The Linguistic Survey of India. India: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 624. ISBN 978-81-85395-27-2.

- ↑ Shapiro, Michael (2002). Songs of the Saints from the Adi Granth. Journal Of The American Oriental Society. p. 924,925.

- ↑ Mann, Gurinder Singh (2001). The Making of Sikh Scripture. United States: Oxford University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-19-513024-9.

- ↑ Brar, Sandeep Singh (1998). "The Sikhism Homepage: Sri Guru Granth Sahib — Authors & Contributors". Retrieved 30 May 2006.

- ↑ Parrinder, Geoffrey (1971). World Religions: From Ancient History to the Present. United States: Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-87196-129-7.

- ↑ "EcoSikh website with reports on Sikh Environment Day activity worldwide". Ecosikh.org. 2013-03-14. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ↑ Sahib, Nanak. Guru Granth Sāhib. p. 75. Retrieved 30 June 2006. "Pilgrimages, fasts, purification and self-discipline are of no use, nor are rituals, religious ceremonies or empty worship."

- ↑ Loehlin, Clinton Herbert (1964) [1958]. The Sikhs and Their Scriptures (Second edition ed.). Lucknow Publishing House. p. 42.

- ↑ "Sikh Reht Maryada — Anand Sanskar: (Sikh Matrimonial Ceremony and Conventions)". Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ↑ Mansukhani, Gobind Singh (1977). Introduction to Sikhism. India: Hemkunt Press. Retrieved 11 June 2006.

- ↑ "Sikh Reht Maryada — Funeral Ceremonies (Antam Sanskar)". Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ↑ Simmonds, David (1992). Believers All: A Book of Six World Religions. Nelson Thornes. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-0-17-437057-4.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Singh Kalsi, Sewa (2007). Sikhism. London: Bravo Ltd. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-85733-436-4.

- ↑ Ballantyne, Tony (2006). Between Colonialism and Diaspora: Sikh Cultural Formations in an Imperial World. Duke University Press. pp. 69–74. ISBN 978-0-8223-3824-6.

- ↑ Takhar, Opinderjit Kaur (2005). Sikh Identity: An Exploration of Groups among Sikhs. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate Publishing. p. 159. ISBN 9780754652021. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ↑ , The Sikh Business Awards

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 "Sikh Reht Maryada, The Definition of Sikh, Sikh Conduct & Conventions, Sikh Religion Living, India". Sgpc.net. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 "Sikh Reht Maryada, The Definition of Sikh, Sikh Conduct & Conventions, Sikh Religion Living, India". Sgpc.net. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ↑ "Sikh Code Of Conduct". Satnamnetwork.com. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ↑ Ethical issues in six religious traditions By Clive Lawton, Peggy Morgan Section C.4.e. ISBN B001PC20N2

- ↑ Srigranth.org – Guru Granth Sahib Page 1253

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 "The Sikhism Home Page: Introduction to Sikhism". Sikhs.org. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ↑ Sikhs and Sikhism, Dr. I.J.Singh, Manohar Publishers.ISBN 978-8173040580

- ↑ "Sikhism, A Complete Introduction" by Dr. H.S. Singha & Satwant Kaur Hemkunt, Hemkunt Press, New Delhi, 1994, ISBN 81-7010-245-6

- ↑ Jhatka, The Sikh Encyclopedia

- ↑ "What is Jhatka Meat and Why?". Sikhs.org. 1980-02-15. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ↑ "Daya Singh Rahit-nama: p2 – Sexual morality". Allaboutsikhs.com. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ↑ Doris R. Jakobsh. Relocating Gender In Sikh History: Transformation, Meaning and Identity. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2003, pp. 39-40

Further reading

- Dilgeer, Dr Harjinder Singh (2008), Sikh Twareekh, publisher Sikh University Press & Singh Brothers Amritsar, 2008.

- Dilgeer, Dr Harjinder Singh (2012), Sikh History (in 10 volumes), publisher Sikh University Press & Singh Brothers Amritsar, 2010–12.

- Duggal, Kartar Singh (1988), Philosophy and Faith of Sikhism, Himalayan Institute Press, ISBN 978-0-89389-109-1

- Kaur, Surjit, Amongst the Sikhs: Reaching for the Stars, New Delhi, Roli Books, 2003 ISBN 81-7436-267-3

- Khalsa, Guru Fatha Singh, Five Paragons of Peace: Magic and Magnificence in the Guru's Way, Toronto, Monkey Minds Press, 2010, ISBN 0968265820, gurufathasingh.com

- Khalsa, Shanti Kaur, The History of Sikh Dharma of the Western Hemisphere, Sikh Dharma, Espanola, NM, 1995 ISBN 0-9639847-4-8

- Singh, Khushwant (2006), The Illustrated History of the Sikhs, Oxford University Press, India, ISBN 978-0-19-567747-8

- Singh, Patwant (1999), The Sikhs, Random House, India, ISBN 978-0-385-50206-1

- Takhar, Opinderjit Kaur, Sikh Identity: An Exploration of Groups Among Sikhs, Ashgate Publishing Company, Burlington, VT, 2005 ISBN 0-7546-5202-5

- Teece, Geoff (2004), Sikhism: Religion in focus, Black Rabbit Books, ISBN 978-1-58340-469-0

- Dilgeer, Dr Harjinder Singh (1997), The Sikh Reference Book, publisher Sikh University Press & Singh Brothers Amritsar, 1997.

- Dilgeer, Dr Harjinder Singh (2005), Dictionary of Sikh Philosophy, publisher Sikh University Press & Singh Brothers Amritsar, 2005.

- Chopra, R. M. (2001), Glory of Sikhism, publisher Sanbun, New Delhi, ISBN 9783473471195

External links

| Find more about Sikhism at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| |

Definitions and translations from Wiktionary |

| |

Media from Commons |

| |

Quotations from Wikiquote |

| |

Source texts from Wikisource |

| |

Textbooks from Wikibooks |

| |

Learning resources from Wikiversity |

- SikhMuseum.com

- Sikh History Web Portal

- Sikhs.org

- Sikh Devotional Music - Kirtan

- Srigranth.org

- Sikh-heritage.co.uk

- Sikh Thematic Philately: Sikh Stamps Collection

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||