Signal averaging

Signal averaging is a signal processing technique applied in the time domain, intended to increase the strength of a signal relative to noise that is obscuring it. By averaging a set of replicate measurements, the signal-to-noise ratio, S/N, will be increased, ideally in proportion to the square root of the number of measurements.

The ideal case

Ideally it is assumed that

- Signal and noise are uncorrelated.

- Signal strength is constant in the replicate measurements.

- Noise is random, with a mean of zero and constant variance in the replicate measurements.

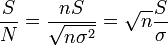

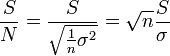

Under these assumptions let the signal strength be denoted by S and let the standard deviation of a single measurement be σ; this represents the noise, N, in one measurement. If n measurements are added together the sum of signal strengths will be nS. For the noise, the standard error propagation formula shows that the variance, σ2, is additive. The variance of the sum is equal to nσ2. Hence the signal-to-noise ratio, S/N, is given by

The equivalent expression for signal averaging is obtained by dividing both numerator and denominator by n.

Thus, in the ideal case S/N increases with the square root of the number of measurements that are averaged. In practice, the assumptions may not be fully realized, this will result in a lower S/N improvement than in the ideal case, but in many cases near-ideal S/N improvement can be achieved.[1]

Time-Locked Signals

Averaging is applied to enhance a time-locked signal component in noisy measurements.

Averaging Odd and Even Trials

A specific way of obtaining replicates is to average all the odd and even trials in separate buffers. This has the advantage of allowing for comparison of even and odd results from interleaved trials. An average of odd and even averages generates the completed averaged result, while the difference between the odd and even averages constitutes an estimate of the noise.

Algorithmic Implementation

The following is a MATLAB simulation of the averaging process:

% create [sz x sz] matrix

% fill the matrix with noise

sz=256;

NOISE_TRIALS=randn(sz);

% create signal with a sine wave

% divide the array SZ by sz/2

SZ=1:sz;

SZ=SZ/(sz/2);

S=sin(2*pi*SZ);

for i=1:sz;

NOISE_TRIALS(i,:) = NOISE_TRIALS(i,:) + S;

end;

% create the average

average=sum(NOISE_TRIALS)/sz;

odd_average=sum(NOISE_TRIALS(1:2:sz,:))/(sz/2);

even_average=sum(NOISE_TRIALS(2:2:sz,:))/(sz/2);

noise_estimate=odd_average-even_average;

% create plot

figure

hold

plot(NOISE_TRIALS(1,:),'g')

plot(noise_estimate,'k')

plot(average,'r')

plot(S)

xlabel('Trials')

ylabel('Amplitude')

title('Signal Averaging')

gtext('Signal: Blue')

gtext('Single trial: Green')

gtext('Noise estimate: Black')

gtext('Average: Red')

The averaging process above, and in general, results in an estimate of the signal. When compared with the raw trace, the averaged noise component is reduced with every averaged trial. When averaging real signals, the underlying component may not always be as clear, resulting in repeated averages in a search for consistent components in two or three replicates. It is unlikely that two or more consistent results will be produced by chance alone.

Non-random Noise

Signal averaging typically relies heavily on the assumption that the noise component of a signal is random, having zero mean, and being unrelated to the signal. However, there are instances in which the noise is not random. A common example of non-random noise is a hum (e.g. 60 Hz noise originating from power lines). To apply the signal averaging technique, a few critical adaptations must be made, and the problem can be avoided by:

- Randomizing the stimulus interval, or

- Using a noninteger stimulus rate (e.g. 3.4 Hz instead of 3.0 Hz)

References

- ↑ Wim van Drongelen. "Signal Processing for Neuroscientists." Academic Press 2008. (Ch. 4, pg 55)

| ||||||||||||||