Sien, Germany

| Sien | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Sien | ||

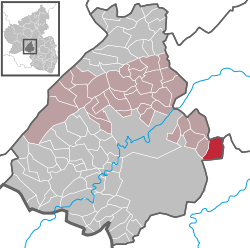

Location of Sien within Birkenfeld district  | ||

| Coordinates: 49°41′41″N 07°30′15″E / 49.69472°N 7.50417°ECoordinates: 49°41′41″N 07°30′15″E / 49.69472°N 7.50417°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Rhineland-Palatinate | |

| District | Birkenfeld | |

| Municipal assoc. | Herrstein | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Otto Schützle | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 8.47 km2 (3.27 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 345 m (1,132 ft) | |

| Population (2012-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 503 | |

| • Density | 59/km2 (150/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 55758 | |

| Dialling codes | 06788 | |

| Vehicle registration | BIR | |

| Website | www.sien.de | |

Sien is an Ortsgemeinde – a municipality belonging to a Verbandsgemeinde, a kind of collective municipality – in the Birkenfeld district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the Verbandsgemeinde of Herrstein, whose seat is in the like-named municipality.

Geography

Location

Sien lies between Idar-Oberstein and Lauterecken northeast of the Baumholder troop drilling ground.

Neighbouring municipalities

Sien borders in the north on the municipality of Otzweiler (Bad Kreuznach district), in the east on the municipality of Hoppstädten (Kusel district; not to be confused with Hoppstädten-Weiersbach), in the south on the municipality of Langweiler (Kusel district; not to be confused with Langweiler in the Birkenfeld district), in the southwest on the municipality of Unterjeckenbach (Kusel district) and the Baumholder troop drilling ground and in the west on the municipality of Sienhachenbach. Sien also meets the municipality of Schmidthachenbach at a single point in the northwest.

History

Celtic times

The earliest traces of habitation in what is now Sien’s municipal area go far back before the Christian era, bearing witness to which are two extensive fields of barrows. There are hundreds here, built by the Treveri, a people of mixed Celtic and Germanic stock, from whom the Latin name for the city of Trier, Augusta Treverorum, is also derived. Among the most important archaeological finds unearthed at one of the two barrows where digs have been undertaken is a beak-spouted clay ewer. Buried with Celtic princes in the time around 400 BC (La Tène A) were Etruscan bronze beak-spouted ewers, a luxury that few could afford. These were for serving Celts as festive wine vessels, even in the afterlife. Grave goods from ordinary people’s graves, however, were humbler things, mostly made of clay. Nowhere had a clay imitation of a bronze Etruscan ewer ever been unearthed, which was somewhat against expectations, until 1972. That year, in Sien, a Celtic warrior’s grave yielded up such a vessel. The humble potter had not merely slavishly copied the Etruscan model, but had also thrown the 29 cm-tall piece on his wheel in such a way that he gave it a thoroughly unique artistic form. The original is to be found at the Trier State Museum, while a replicas are on display at the local history museum in Birkenfeld and in Sien.[2]

Roman times

Archaeological finds, of which there have been many, also establish that Sien’s municipal area was settled in Roman times (2nd to 4th century AD). Most noteworthy among the finds from this era has been a well preserved column made of light-coloured sandstone. Presumably it belonged to the portico villa of a Roman estate.

The column, unearthed in 1973, was carved out of a single block of stone (a monolith). With the capital and the abacus, it measures some 2 m tall. It tapers slightly towards the top and has a diameter of roughly 36 cm. The column’s surface is, given sandstone’s characteristics, rough. In two places, just above the base and also just below the necking, is a fine groove turned on a lathe. On the whole, it could be an example of the Tuscan style.

The column can nowadays be found being used as a support for the little porch at the entrance to the Evangelical church in Sien.[3]

Frankish times

Today’s village of Sien was founded by Germanic, namely Frankish, settlers who made it their home after the Roman Empire had fallen. Bearing witness to this is the village’s own name, Sien, which likely derives from the Old High German word sinithi (“grazing land”).

Since the parish of Sien is considered one of the oldest ones in the area, the village may well have been one of the earliest Frankish foundings in the time between the 6th and 10th centuries. Moreover, Sien was the hub of a high court district, witnessed as early as 970, and a fief granted by the Salian emperor to the Emichones, gau counts in the Nahegau, who later called themselves the Waldgraves and Raugraves.

The Nahegau was divided into administrative zones called Hochgerichte (“high courts”). The one whose seat was in Sien was called the Hochgericht auf der Heide (“High Court on the Heath”). The Hochgericht comprised a vast area (18 650 ha) between the Nahe and the Glan with all together 50 population centres, although some of these later vanished. Court was held at least once a year on the heath near Sien (hence its name). The count or the Schultheiß, as the king’s representative, administered justice along with 14 Heideschöffen (“heath Schöffen”, or, roughly “heath lay jurists”). Today the cadastral names Königswäldchen (“King’s Little Wood”) and Galgenberg (“Gallows Mountain”) recall the former execution places.[4]

Middle Ages

In 1128, Sien had its first documentary mention in the so-called Adalbert Document, in which it says that Archbishop of Mainz Ruthard had bestowed upon the Disibodenberg Monastery – quite possibly as an economic hedge – one Hufe of land (this was between 30 and 60 Morgen, and a Morgen itself could be between 0.2 and 1 ha) in Sien (“…et in Sinede hubam”).

In this same document, the namesake Archbishop of Mainz Adalbert (1109-1137) confirmed his predecessor’s donations to Disibodenberg. The donation of the Hufe of land might have taken place about 1108, for it was then that building work on a new Benedictine monastery began at the forks of the Nahe and Glan, after the old one had been destroyed in the 10th century and forsaken by the monks. The Adalbert Document is reproduced in the Disibodenberg Monastery’s cartulary, now kept at the state archive at Darmstadt.

Over the course of history, the village has been known as Sinede, Synede, Synde, Syende, Siende and Syne, among other names, before settling on the currently customary form, Sien.

Divisions of inheritance and feuds led to an ever greater splintering of the gau counts’ formerly unified holding. Thus, Sien passed by way of inheritance in 1112 to the Counts of Veldenz, the Emichones’ successors. From the 13th century, Sien itself was even divided. One part belonged to the Waldgraves of Grumbach – and as of 1375 to the Waldgraves and Rhinegraves of Kyrburg – while the other part was held by the Counts of Loon (a place nowadays in Belgium), who were offspring of the Vögte and prefects of the Foundation of Mainz, and thereby also possibly heirs to the Mainz church estate in Sien.

In 1325, the Counts of Loon, who in the late 13th century built a moated castle on their part of Sien, enfeoffed the knight Kindel von Sien with the castle and half the village of Sien, as well as with further, considerable holdings. The small castle was known in documents as Festes hus (“steadfast house”), but for all its steadfastness, on 28 September 1504, it was destroyed in the Landshut War of Succession and was never restored. All that is left of it now is the former castle well. There is also a memorial plaque on Schloßstraße (“Castle Street”) in the village. Two local cadastral names also recall the old castle: “Schlosswies” (“Castle Meadow”) and “Am Weiher” (“At the Pond” – meaning of course the former moat). The part of the municipal area where the castle once stood was officially known as Sienerhöfe (“Sien Estates”), but it was never locally known as anything other than the Schloss (“Castle”), and accordingly, the inhabitants were called the Schlösser. The Counts, though, ceded the feudal overlordship over their Sien holdings in 1334 to the Waldgraves of Dhaun. The then Count of Loon and Chiny, Ludwig, issued a writ releasing all his vassals and subjects who were part of the castle holding from any and all duty and loyalty to him, but in the same breath, Ludwig reminded them that they now owed their new overlord, the Waldgrave of Dhaun, Johannes, the same as they had owed their old overlord. The writ bore Ludwig’s seal on the back.

An enfeoffment document gives information about the fief. It apparently comprised the castle, half the village of Sien, half the village of Sienhoppstädten, the lordly rights as they pertained to the church and the tithes from Sien, Sienhoppstädten, Schweinschied, Selbach, Reidenbach, Oberhachenbach and Niederhachenbach.

In 1431, the Knights of Sien died out in the male line. Schonetta von Siende, the last knightly feudal lord’s niece, brought the Sien fief by marriage to Reinhard von Sickingen to the Lords of Sickingen, whose best known family member was her grandson, Franz von Sickingen. Schonetta von Siende was the last of the knightly house of Sien. Her first marriage was to the knight Hermann Boos von Waldeck, but he died young. A son that she bore in this union inherited parts of Dickesbach and Schmidthachenbach from the Sien fief. Schonetta married her second husband in 1449, and bore him a son, Schwicker von Sickingen, who later became Franz von Sickingen’s father. Schonetta died on 1 January 1483 in Kreuznach. In the upheaval of the Reformation, her bones were transferred from Kreuznach to Ebernburg, where the family Sickingen kept its seat. Thereafter, however, the trail is lost, and the whereabouts of Schonetta’s bones is now unknown. There is, however, still a stone to her memory at the parish church in Sien. It dates from roughly 1560.[5]

Age of Absolutism

In 1765, the Sickingens sold off their holdings in Sien to Johann XI Dominik Albert, Prince at Salm-Kyrburg (known as Prince Dominik) and owner of the other half of Sien, thereby ending the age of two lords holding the village as a condominium. One thing left over from that age, though, was the denominational split between Catholics and Protestants that had arisen from the two lords’ different policies. On the other hand, under Prince Dominik’s enlightened rule, trade and crafts blossomed, which was something sorely needed. Hardly needed, though, were some of the subsequent events, such as the Plague, the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) and the Nine Years' War (1688-1697; known in Germany as the Pfälzischer Erbfolgekrieg, or War of the Palatine Succession), which laid the land waste and sharply decimated the local population. According to one memorandum, in 1698, Sien comprised no more than 15 houses.

Prince Dominik was one of the most important rulers among the Lords of Salm, to whom the Oberamt of Kirn passed after the Waldgravial-Rhinegravial line of Kyrburg died out. He was born in 1708 in Mechelen, nowadays in Belgium, and despite being orphaned at the age of eight, this Jesuit-educated boy lived what was at that time a relatively charmed life as an heir to the Salm estates. His father’s death, of course, meant that he inherited his father’s holdings, the lordship of Leuze in the County of Hainaut (nowadays mostly in the Belgian province of Hainaut, but with parts in the neighbouring French Department of Nord). Thus, even as a youngster, he could enjoy a carefree life of leisure in Vienna, the more so when he and his brother Philipp Joseph received the Oberamt of Kirn in 1743. This included the Schultheißerei of Sien, along with half the village of the same name.

Two years later, both brothers were raised to princely status. Dominik now underwent a gradual shift in his ways of thinking and in his attitude towards life, which was helped along by various educational travels, whereafter he permanently moved house in 1763 to Kirn so that he could quite humbly live amongst his subjects. As an enlightened prince, he was very concerned about their welfare, and worried particularly about their education and religious upbringing.

Prince Dominik built himself many lasting monuments, mostly ecclesiastical buildings. In Sien, he had the old church, which had fallen into disrepair, torn down in 1765, and on the same site, he had built a new church in plain, rustic Baroque style with a tower topped with an onion dome. Today, this is the Evangelical church. However, at the time it was built, Prince Dominik stipulated that it was to be open for use by both Catholics and Protestants, thus creating a simultaneum.

The hunting lodge in Sien, now run as an inn, is also one of Prince Dominik’s projects. In 1770 he had it built by his court master builder, Johann Thomas Petri. It features a triaxial middle risalto under a triangular spire light, a slated mansard roof and above the doorway a sandstone relief by Bernkastel sculptor Johann Philipp Maringer showing two wildmen bearing the princely coat of arms.

When Johann XI Dominik Albert, Prince at Salm-Kyrburg, died on 2 June 1778, there was great and sincere mourning. His remains lie in the quire at the Evangelical Kirche am Hahnenbach (“Church on the Hahnenbach”) in Kirn.[6]

Modern times

The 1789 French Revolution marked the end of princely rule in the little Principality of Salm-Kyrburg, to which Sien belonged. The ideals of Liberté, égalité, fraternité were brought into the territorially splintered land of Germany by French Revolutionary troops. Soon, la République française stretched all the way to the Rhine’s left bank. On 10 March 1798 the liberty pole was put up in Sien. Sieners were no longer serfs, but rather free French citizens. The properties formerly held by the last Salm-Kyrburg Prince, Friedrich III, Prince Dominik’s nephew, who had already been put to death by guillotine in Paris by 1794, were confiscated and auctioned off to the highest bidder. Even the Prince’s hunting lodge got a new, untitled owner. Sixteen years French times lasted (1798-1814), during which Sien was raised to a mairie (“mayoralty”) for the surrounding villages of Sienhachenbach, Oberreidenbach, Dickesbach, Kefersheim, Illgesheim, Hoppstädten, Oberjeckenbach and Unterjeckenbach.

The lands acquired by France on the Rhine’s left bank were subdivided on the French model into departments, arrondissements and cantons. The Mairie of Sien belonged to the Canton of Grumbach, the Arrondissement of Birkenfeld and the Department of Sarre, whose seat was at Trier.

Even after the German campaign that put an end to the War of the Sixth Coalition in the Napoleonic Wars, Sien remained a mayoralty in the Saxe-Coburg-ruled Principality of Lichtenberg with its capital at Sankt Wendel. This territorial arrangement was set forth at the Congress of Vienna. It retained the status when the Prussians took over in 1834. In Saxe-Coburg times, and Prussian times, too, the Bürgermeisterei (“Mayoralty”) of Sien comprised Sien and Sienerhöfe (where the castle had been), Sienhachenbach, Schmidthachenbach, Mittelreidenbach, Oberreidenbach, Weierbach, Dickesbach, Zaubach, Kefersheim, Wickenhof, Ehlenbach, Wieselbach, Kirchenbollenbach, Mittelbollenbach and Nahbollenbach. In Prussian times, the Amtshaus (administrative centre for the Amt) was built. With the new lords, a gradual economic upswing set in, reaching a peak in the latter half of the 19th century. Many urban-style houses and the Gothic Revival Catholic church, upon whose consecration in 1892 the simultaneum ended, still bear witness to the wealth at that time.

Sien’s small Jewish community enjoyed a heyday in the 19th century, too, which found architectural expression in the synagogue, built about 1845. Despite the favourable economic development, however, many Sieners chose to emigrate, with most going to the United States.

The economic upswing brought along with it a building boom. As well as the houses and the Catholic church mentioned above, the Evangelical parish built a new schoolhouse in 1838 out of its own financial resources. A Catholic schoolhouse followed in 1868. In 1871, Sien had roughly 600 inhabitants, of whom some 70 were of Jewish background. There was a vast array of retail businesses, as well as four inns and a brewery. A major knitting mill, a brickyard and a construction company also set up shop in the village. A full range of craft businesses was also available then.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries also saw improvements in infrastructure. Streets were cobbled, and lit by lanterns at night, modern (for that time) firefighting equipment was secured, as well as a steam-powered threshing machine, and a watermain was built.

In the 20th century, though, Sien suffered several unfortunate blows. The railways through the Nahe and Glan valleys bypassed the village, stripping it of its hitherto enjoyed status as an economic centre of sorts. This led in turn to the loss of the mayoralty, which had to be yielded to Weierbach in 1909. The structural shift in agriculture and the expropriation of land by the Third Reich for the new Baumholder troop drilling ground in 1938, displacing roughly 4,000 people and stripping Sien of a great deal of its outlying municipal area, led to a further loss for the municipality’s position as an economic and political force locally. The once well attended markets held in the village died out, and the population figure began to shrink.

On 1 April 1939, Sienerhöfe, which until this time had been a self-administering municipality, was amalgamated with Sien.[7]

In the early 21st century, the economic downturn has been turned round somewhat with the location of modern industrial operations in the municipality.

Jewish community

The first written records of a permanent Jewish presence in Sien go back to the 18th century. In the Verzeichnis deren in dem hochfürstlichen salm-kyrburgischen Ort Syen unter hochfürstlichem Schutz wohnenden Juden (“Directory of Jews Living in the High-Princely Salm-Kyrburg Village of Syen Under High-Princely Protection”), dated 28 March 1760, five Jewish household heads are named. There were 42 Jewish inhabitants in 1808. Numerically, the peak was reached in 1852 when there were 72 registered Jewish inhabitants in Sien. This was out of a total population of 530. Although the Jewish population had been rising in the earlier half of the 19th century, in the latter half, it shrank. This trend continued after the turn of the century. There were 36 in 1895, and only 10 by 1925. Sien’s last six Jews were deported by the Nazis in 1942 and murdered in the Holocaust.

Sien’s Jews belonged mostly to two families, Rothschild and Schlachter. To be sure, there were other surnames, but these two predominated. Recalling the former Jewish community and its culture today are very few things. Among these are the graveyard, a mikveh and a Jewish livestock merchant’s account book.[8]

Politics

Municipal council

The council is made up of 12 council members, who were elected by majority vote at the municipal election held on 7 June 2009, and the honorary mayor as chairman.[9]

Mayor

Sien’s mayor is Otto Schützle, and his deputies are Burkhard Müller and Bernd Schuck.[10]

Coat of arms

The municipality’s arms might be described thus: Per fess enhanced in chief party per pale Or five roundels, two, one and two, sable and gules two salmon addorsed argent, in base argent two scarpes vert between which six oakleaves proper, one, three and two.

Culture and sightseeing

Buildings

The following are listed buildings or sites in Rhineland-Palatinate’s Directory of Cultural Monuments:[11]

- Evangelical parish church, Kirchweg – aisleless church, west tower with doubled helmed roof, 1768, architect Johann Thomas Petri, Kirn; organ, 1870 by Georg Karl Ernst Stumm, Sulzbach; Knights of Sien memorial armorial stone, 1560

- Saint Lawrence’s Catholic Parish Church (Pfarrkirche St. Laurentius), Fürst-Dominik-Straße – two-naved hall church, Gothic Revival red sandstone building, 1892/1893, architect Walther, Lauterecken; décor; missionary cross

- Fürst-Dominik-Straße, at the graveyard – Friedrich Schmidt tomb, 1888, hewn oaken log; two cast-iron Crucifixes

- Fürst-Dominik-Straße 23 – so-called Schloss (castle); three-floor building with mansard roof, gable-topped middle risalto, 1771, architect Johann Thomas Petri, Kirn

- Fürst-Dominik-Straße 24 – L-shaped, steep-gabled farmhouse, marked 1850, essentially surely older

- Im Winkel 10 – stately Quereinhaus (a combination residential and commercial house divided for these two purposes down the middle, perpendicularly to the street), marked 1856

- In der Hohl 11 – former mayoral office; seven-axis plastered building with knee wall, 1860

- Schloßstraße 4 – Baroque Quereinhaus, marked 1806, possibly older

- Near Sickingerstraße 9 – bridge built with jack arch, yellow sandstone, marked 1927

- Jewish graveyard, southeast of the village in the woods (monumental zone) – 48 gravestones in situ, 1847 to 1937, mainly inscribed in Hebrew-German

- Wayside cross, west of the village – processional cross, yellow sandstone

Economy and infrastructure

Transport

Sien lies on Bundesstraße 270. Serving nearby Lauterecken is a railway station on the Lautertalbahn (Kaiserslautern–Lauterecken).

Further reading

- Erich Gemmel: Festschrift zur 1000-Jahr-Feier der Gemeinde Sien; Sien 1970

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: Römerzeitliche Spuren der Besiedlung und Kultur in Sien im 2./3. Jhdt n. Chr.; Sien 1991

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: Die „Siener Tonschnabelkanne“ - ein Zeugnis keltischer Töpferkunst; Sien 1994

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: Vor 25 Jahren: 1000-Jahr-Feier der Gemeinde Sien – Eine Dokumentation; Sien 1995

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: JOHANN XI. DOMINIK ALBERT Fürst zu Salm-Kyrburg, das Zeitalter des Absolutismus und SIEN; Sien 1996

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: Sien – wie es einmal war - Bilder und Geschichten aus der Vergangenheit; Sien 1997

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: Die ehemalige Jüdische Gemeinde Sien – Spuren und Erinnerungen; Sien 1998

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: Die ehemalige Jüdische Gemeinde Sien – Spuren und Erinnerungen; Kurzfassung, Sien 1999

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: Vergessene Geschichten, die uns die Siener Flurnamen erzählen; Sien 2001

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: 55 Siener-Wind-Geschichten – Denkwürdiges aus der über 1000 Jahre alten Geschichte des Ortes Sien; Sien 2003

- Ulrich Eckhoff: „Siener Originale“. In Heimatkalender 2004 Landkreis Birkenfeld, Idar-Oberstein 2003 , S. 236f

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: „Moses Herz - unvergessen“. In Heimatkalender 2005 Landkreis Birkenfeld, Idar-Oberstein 2004 , S. 234f

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: „Willy Römer - Fotograf aus Leidenschaft“. In Heimatkalender 2006 Landkreis Birkenfeld, Idar-Oberstein 2005 , S. 169f

- Ulrich Eckhoff: „Ein Stein wider das Vergessen – Gedenkfeier für Kurt Schlachter“. In: Heimatkalender 2007 Landkreis Birkenfeld, Idar-Oberstein 2006 , S. 88f

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: „Wo Räuber und Fürsten verkehrten“. In Heimatkalender 2008 Landkreis Birkenfeld, Bad Kreuznach 2007 , S. 236f

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: „Harry Rothschild – ein deutschjüdisches Schicksal“. In: Heimatkalender 2009 Landkreis Birkenfeld, Bad Kreuznach 2008 , S. 161f

- Ruth und Ulrich Eckhoff: „Das ehemalige Gendarmeriedienstgebäude“. In: Heimatkalender 2010 Landkreis Birkenfeld, Bad Kreuznach 2009 , S. 131f

References

- ↑ "Bevölkerung der Gemeinden am 31.12.2012". Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). 2013.

- ↑ Sien’s Celtic history

- ↑ Sien’s Roman history

- ↑ Sien’s Frankish history

- ↑ Sien’s mediaeval history

- ↑ Sien’s history in the Age of Absolutism

- ↑ Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, Band 450: Amtliches Gemeindeverzeichnis für das Deutsche Reich, Teil I, Berlin 1939; Seite 284

- ↑ Sien’s modern history

- ↑ Kommunalwahl Rheinland-Pfalz 2009, Gemeinderat

- ↑ Sien’s executive

- ↑ Directory of Cultural Monuments in Birkenfeld district

External links

- Municipality’s official webpage (German)

- This article incorporates information from the German Wikipedia.