Short-rate model

A short-rate model, in the context of interest rate derivatives, is a mathematical model that describes the future evolution of interest rates by describing the future evolution of the short rate, usually written  .

.

The short rate

Under a short rate model, the stochastic state variable is taken to be the instantaneous spot rate.[1] The short rate,  , then, is the (continuously compounded, annualized) interest rate at which an entity can borrow money for an infinitesimally short period of time from time

, then, is the (continuously compounded, annualized) interest rate at which an entity can borrow money for an infinitesimally short period of time from time  . Specifying the current short rate does not specify the entire yield curve. However no-arbitrage arguments show that, under some fairly relaxed technical conditions, if we model the evolution of

. Specifying the current short rate does not specify the entire yield curve. However no-arbitrage arguments show that, under some fairly relaxed technical conditions, if we model the evolution of  as a stochastic process under a risk-neutral measure

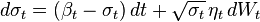

as a stochastic process under a risk-neutral measure  then the price at time

then the price at time  of a zero-coupon bond maturing at time

of a zero-coupon bond maturing at time  is given by

is given by

where  is the natural filtration for the process. Thus specifying a model for the short rate specifies future bond prices. This means that instantaneous forward rates are also specified by the usual formula

is the natural filtration for the process. Thus specifying a model for the short rate specifies future bond prices. This means that instantaneous forward rates are also specified by the usual formula

Particular short-rate models

Throughout this section  represents a standard Brownian motion under a risk-neutral probability measure and

represents a standard Brownian motion under a risk-neutral probability measure and  its differential. Where the model is lognormal, a variable

its differential. Where the model is lognormal, a variable  , is assumed to follow an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process and

, is assumed to follow an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process and  is assumed to follow

is assumed to follow  .

.

One-factor short-rate models

Following are the one-factor models, where a single stochastic factor – the short rate – determines the future evolution of all interest rates. Other than Rendleman–Bartter and Ho–Lee, which do not capture the mean reversion of interest rates, these models can be thought of as specific cases of Ornstein–Uhlenbeck processes. The Vasicek, Rendleman–Bartter and CIR models have only a finite number of free parameters and so it is not possible to specify these parameter values in such a way that the model coincides with observed market prices ("calibration"). This problem is overcome by allowing the parameters to vary deterministically with time.[2][3] In this way, Ho-Lee and subsequent models can be calibrated to market data, meaning that these can exactly return the price of bonds comprising the yield curve. Here, the implementation is usually via a binomial tree (lattice).[4]

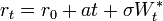

- Merton's model (1973) explains the short rate as

: where

: where  is a one-dimensional Brownian motion under the spot martingale measure.[5]

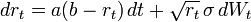

is a one-dimensional Brownian motion under the spot martingale measure.[5] - The Vasicek model (1977) models the short rate as

; it is often written

; it is often written  .[6]

.[6] - The Rendleman–Bartter model (1980) explains the short rate as

.[7]

.[7] - The Cox–Ingersoll–Ross model (1985) supposes

, it is often written

, it is often written  . The

. The  factor precludes (generally) the possibility of negative interest rates.[8]

factor precludes (generally) the possibility of negative interest rates.[8] - The Ho–Lee model (1986) models the short rate as

.[9]

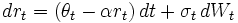

.[9] - The Hull–White model (1990)—also called the extended Vasicek model—posits

. In many presentations one or more of the parameters

. In many presentations one or more of the parameters  and

and  are not time-dependent. The model may also be applied as lognormal. Lattice-based implementation is usually trinomial.[10]

are not time-dependent. The model may also be applied as lognormal. Lattice-based implementation is usually trinomial.[10] - The Black–Derman–Toy model (1990) has

![d\ln(r)=[\theta _{t}+{\frac {\sigma '_{t}}{\sigma _{t}}}\ln(r)]dt+\sigma _{t}\,dW_{t}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/b/2/d/0/b2d04d37047657ec3379d3310c054d8a.png) for time-dependent short rate volatility and

for time-dependent short rate volatility and  otherwise; the model is lognormal.[11]

otherwise; the model is lognormal.[11] - The Black–Karasinski model (1991), which is lognormal, has

![d\ln(r)=[\theta _{t}-\phi _{t}\ln(r)]\,dt+\sigma _{t}\,dW_{t}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/a/9/7/8/a978b221f2b48532d0912fa7e4301193.png) .[12] The model may be seen as the lognormal application of Hull–White;[13] its lattice-based implementation is similarly trinomial (binomial requiring varying time-steps).[4]

.[12] The model may be seen as the lognormal application of Hull–White;[13] its lattice-based implementation is similarly trinomial (binomial requiring varying time-steps).[4] - The Kalotay–Williams–Fabozzi model (1993) has the short rate as

, a lognormal analogue to the Ho–Lee model, and a special case of the Black–Derman–Toy model.[14]

, a lognormal analogue to the Ho–Lee model, and a special case of the Black–Derman–Toy model.[14]

Multi-factor short-rate models

Besides the above one-factor models, there are also multi-factor models of the short rate, among them the best known are the Longstaff and Schwartz two factor model and the Chen three factor model (also called "stochastic mean and stochastic volatility model"). Note that for the purposes of risk management, "to create realistic interest rate simulations," these Multi-factor short-rate models are sometimes preferred over One-factor models, as they produce scenarios which are, in general, better "consistent with actual yield curve movements".[15]

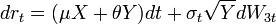

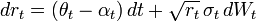

- The Longstaff–Schwartz model (1992) supposes the short rate dynamics are given by:

,

,  , where the short rate is defined as

, where the short rate is defined as  .[16]

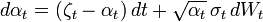

.[16] - The Chen model (1996) which has a stochastic mean and volatility of the short rate, is given by :

,

,  ,

,  .[17]

.[17]

Other interest rate models

The other major framework for interest rate modelling is the Heath–Jarrow–Morton framework (HJM). Unlike the short rate models described above, this class of models is generally non-Markovian. This makes general HJM models computationally intractable for most purposes. The great advantage of HJM models is that they give an analytical description of the entire yield curve, rather than just the short rate. For some purposes (e.g., valuation of mortgage backed securities), this can be a big simplification. The Cox–Ingersoll–Ross and Hull–White models in one or more dimensions can both be straightforwardly expressed in the HJM framework. Other short rate models do not have any simple dual HJM representation.

The HJM framework with multiple sources of randomness, including as it does the Brace–Gatarek–Musiela model and market models, is often preferred for models of higher dimension.

References

- ↑ Short rate models, Prof. Andrew Lesniewski, NYU

- ↑ An Overview of Interest-Rate Option Models, Prof. Farshid Jamshidian, University of Twente

- ↑ Continuous-Time Short Rate Models, Prof Martin Haugh, Columbia University

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Binomial Term Structure Models, Mathematica in Education and Research, Vol. 7 No. 3 1998. Simon Benninga and Zvi Wiener.

- ↑ Merton, Robert C. (1973). "Theory of Rational Option Pricing". Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 4 (1): 141–183. doi:10.2307/3003143.

- ↑ Vasicek, Oldrich (1977). "An Equilibrium Characterisation of the Term Structure". Journal of Financial Economics 5 (2): 177–188. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(77)90016-2.

- ↑ Rendleman, R.; Bartter, B. (1980). "The Pricing of Options on Debt Securities". Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 15: 11–24. doi:10.2307/2979016.

- ↑ Cox, J.C., J.E. Ingersoll and S.A. Ross (1985). "A Theory of the Term Structure of Interest Rates". Econometrica 53: 385–407. doi:10.2307/1911242.

- ↑ T.S.Y. Ho and S.B. Lee (1986). "Term structure movements and pricing interest rate contingent claims". Journal of Finance 41. doi:10.2307/2328161.

- ↑ John Hull and Alan White (1990). "Pricing interest-rate derivative securities". Review of Financial Studies 3 (4): 573–592.

- ↑ Black, F.; Derman, E. and Toy, W. (1990). "A One-Factor Model of Interest Rates and Its Application to Treasury Bond Options". Financial Analysts Journal: 24–32.

- ↑ Black, F.; Karasinski, P. (1991). "Bond and Option pricing when Short rates are Lognormal". Financial Analysts Journal: 52–59.

- ↑ Short Rate Models, Professor Ser-Huang Poon, Manchester Business School

- ↑ Kalotay, Andrew J.; Williams, George O.; Fabozzi, Frank J. (1993). "A Model for Valuing Bonds and Embedded Options". Financial Analysts Journal (CFA Institute Publications) 49 (3): 35–46. doi:10.2469/faj.v49.n3.35.

- ↑ Pitfalls in Asset and Liability Management: One Factor Term Structure Models, Dr. Donald R. van Deventer, Kamakura Corporation

- ↑ Longstaff, F.A. and Schwartz, E.S. (1992). "Interest Rate Volatility and the Term Structure: A Two-Factor General Equilibrium Model". Journal of Finance 47 (4): 1259–82.

- ↑ Lin Chen (1996). "Stochastic Mean and Stochastic Volatility — A Three-Factor Model of the Term Structure of Interest Rates and Its Application to the Pricing of Interest Rate Derivatives". Financial Markets, Institutions, and Instruments 5: 1–88.

Further reading

- Martin Baxter and Andrew Rennie (1996). Financial Calculus. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55289-9.

- Damiano Brigo, Fabio Mercurio (2001). Interest Rate Models – Theory and Practice with Smile, Inflation and Credit (2nd ed. 2006 ed.). Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-22149-4.

- Gerald Buetow and James Sochacki (2001). Term-Structure Models Using Binomial Trees. The Research Foundation of AIMR (CFA Institute). ISBN 978-0-943205-53-3.

- Andrew J.G. Cairns (2004). Interest Rate Models – An Introduction. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11894-9.

- Andrew J.G. Cairns (2004). Interest-Rate Models; entry in Encyclopaedia of Actuarial Science. John Wiley and Sons. 2004. ISBN 0-470-84676-3.

- K. C. Chan, G. Andrew Karolyi, Francis Longstaff, and Anthony Sanders (1992). An Empirical Comparison of Alternative Models of the Short-Term Interest Rate. The Journal of Finance, Vol. XLVII, No. 3 July 1992.

- Lin Chen (1996). Interest Rate Dynamics, Derivatives Pricing, and Risk Management. Springer. ISBN 3-540-60814-1.

- Rajna Gibson, François-Serge Lhabitant and Denis Talay (1999). Modeling the Term Structure of Interest Rates: An overview. The Journal of Risk, 1(3): 37–62, 1999.

- Lane Hughston (2003). The Past, Present and Future of Term Structure Modelling; entry in Peter Field (2003). Modern Risk Management. Risk Books. ISBN 9781906348304.

- Jessica James and Nick Webber (2000). Interest Rate Modelling. Wiley Finance. ISBN 0-471-97523-0.

- Robert Jarrow (2002). Modelling Fixed Income Securities and Interest Rate Options (2nd ed.). Stanford Economics and Finance. ISBN 0-8047-4438-6.

- Robert Jarrow (2009). The Term Structure of Interest Rates. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 2009, vol. 1, issue 1, pages 69-96.

- F.C. Park (2004). "Implementing Interest Rate Models: a Practical Guide". CMPR Research Publication.

- Riccardo Rebonato (2002). Modern Pricing of Interest-Rate Derivatives. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08973-6.

- Riccardo Rebonato (2003). "Term-Structure Models: a Review". Royal Bank of Scotland Quantitative Research Centre Working Paper.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![P(t,T)={\mathbb {E}}^{Q}\left[\left.\exp {\left(-\int _{t}^{T}r_{s}\,ds\right)}\right|{\mathcal {F}}_{t}\right]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/8/1/8/b/818beca3da49aa85e2949f82398bc8fb.png)