Sholom Dovber Schneersohn

| Sholom Dovber Schneersohn | |

|---|---|

| Lubavitcher Rebbe | |

The Rebbe Nishmoso Eden | |

| Term | 10 September 1892 OS – 21 March 1920 NS |

| Full name | Sholom Dovber Schneersohn |

| Main work | Yom Tov Shel Rosh Hashana, 5666, Sefer HaMaamarim, 5672 |

| Born |

24 October 1860 OS Lyubavichi |

| Died |

21 March 1920 NS Rostov-on-Don |

| Dynasty | Chabad Lubavitch |

| Predecessor | Shmuel Schneersohn |

| Successor | Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn |

| Father | Shmuel Schneersohn |

| Mother | Rivkah (granddaughter of Dovber Schneuri) |

| Wife | Sterna Sarah (daughter of Yosef Yitzchok of Ovruch) |

| Children | Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn |

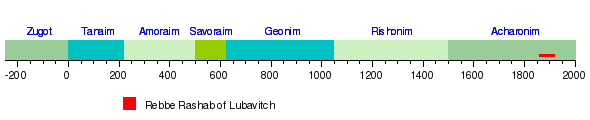

Sholom Dovber Schneersohn (Hebrew: שלום דובער שניאורסאהן) was an Orthodox rabbi and the fifth Rebbe (spiritual leader) of the Chabad Lubavitch chasidic movement. He is also known as "the Rebbe nishmosei eiden" (whose soul is in Eden) and as "the Rebbe Rashab" (for Reb Sholom Ber).

His teachings represent the emergence of an emphasis on outreach that later Chabad Rebbes would develop into a major theme.[1]

Life

He was born in Lubavitch, on 20 Cheshvan 1860, the second son of Shmuel Schneersohn, the fourth Chabad Rebbe.[2] In 1882, when his father died, he was not quite 22 years old, and his brother Zalman Aharon was not much older. A period followed, during which both brothers fulfilled some of the tasks of a rebbe, but neither felt ready to take on the title and responsibilities. Over this period he gradually took on more responsibilities, particularly in dealing with the impact of the May Laws, and on Rosh Hashanah 5643 (10 September 1892 OS) he accepted the leadership of the Lubavitch movement.[citation needed]

He married his cousin, Rebbetzin Shterna Sara Schneersohn. She was the daughter of Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn of Avorutch, a son of the Tzemach Tzedek. They had one son whom they named Yosef Yitzchok after Rebbetzin Shterna Sara's father. Yosef Yitzchok would later succeed his father as Rebbe.

In his early 40s he suffered a loss of sensation in his left hand, and in 1903 he spent two months in Vienna, where Sigmund Freud treated him with electrotherapy. The treatment had some success, restoring some feeling to the hand, but he was unable to stay in Vienna longer than two months. When he returned home he attempted to continue his treatment with a small machine that he had bought in Vienna, but experienced no further improvement and eventually gave up.[3]

In 1915, as the fighting in World War I neared Lubavitch, the Rashab moved to Rostov-on-Don. As Bolshevik forces approached Rostov he considered moving to Turkey, and prepared all the necessary paperwork; his only extant picture comes from his Turkish visa, since he usually refused to be photographed. But eventually he decided to stay in Rostov, where he died on 21 March 1920.[4]

During the construction of the "Rostov Palace of Sport" on top of the Old Jewish Cemetery in 1940, his remains were secretly moved by a devout group of chassidim to a different burial site where they are located to this day in the "Rostov Jewish Cemetery." While relocating his grave, the chassidim found his body full and not decomposed even though this was a full twenty years later. His grave is visited daily by followers of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement who come from all over the world.[5]

Leadership

Schneersohn established the first Chabad yeshiva, Tomchei Temimim, in 1897. In 1911 he established another yeshivah, Toras Emes, in Palestine, and in 1916 he established a yeshivah in Georgia. Avrum Erlich has argued that it was these institutions that made Lubavitch the dominant of the various Chabad hasidic movements.[6]

He maintained a lengthy correspondence, not only with Chabad Chasidim in other countries, but also with non-Chabad chasidim and members of other groups who wrote to him for advice. He also met with other Jewish and hasidic leaders, working with them on issues such as education, unity, policy, and strategy.[6] He was held in very high esteem by the Chofetz Chaim, so much so that the Chofetz Chaim declared of him, "the words of the [Lubavitcher] Rebbe are holy, and anyone who argues disagrees with him [should know that] it is as if he is disagreeing with Moses."[7]

Schneersohn promoted Jewish agricultural settlement, and the creation of employment for Jews, particularly those displaced by the May Laws. He was a prominent opponent of Zionism, both in its secular and religious versions, and a staunch ally of Reb Chaim Brisker. In 1903 he published Kuntres Uma'ayan, which contained a strong polemic against Zionism. He was deeply concerned that secular nationalism would replace Judaism as the foundation of Jewish identity.[8] Together with Reb Chaim he joined and supported Machazikei Hadas - a union of Eastern European haredim and the forerunner of the Agudah[9] - but in 1912, when the Agudah was formed in Katowice, Reb Chaim raised 18 objections to its constitution, and the Rashab kept Lubavitch out of the Agudah.[10]

After the February Revolution, elections were called for Jewish city councils and a General Jewish Assembly. The Rebbe Rashab worked tirelessly to organize a religious front with a center and a special office that would deal with it all. For this reason, he called a unique conference of all the Torah giants throughout Russia. This conference was held in 1917 in Moscow, and was preceded by a meeting of the leading Rabbis, to decide which matters would be discussed there. This smaller meeting was held in Petrograd. However, because the participants in this meeting were few and in a hurry to return home, the Moscow conference failed to yield proper results. Thus, it was necessary to convene once again, this time in Kharkiv in 1918, to discuss the elections for the General Jewish Assembly.[11]

His worries about the Mountain Jews, or Berg Yidden, led him to send a famous Mashpia, Rabbi Shmuel Levitin of Rakshik, to the Caucasus to set up institutions to bring them closer to traditional Judaism,[2] setting a precedent for his two successors as Lubavitcher Rebbe, who conducted similar activities.

.jpg) |

| Part of a series on |

| Chabad |

|---|

| Rebbes |

| History |

| Organizations |

| Notable figures |

| Community rabbis |

| Notable emissaries |

| Notable Mashpiim |

| Communities |

| Texts |

| Schools |

| Outreach |

| Terminology |

| Controversies |

|

| Chabad offshoots |

Distinguished disciples of the Rebbe Rashab include Reb Itche Der Masmid, Reb Nissan Neminov, and Reb Zalman Moishe HaYitzchaki.[12]

Works

Known informally as "Rambam (Maimonides) of Chabad Chassidus" (from his encyclopedic work on developing Chabad Chassidic philosophy into an organized system), Rebbe Rashab was a prolific writer on Chabad theology. Much of his work has been published in Hebrew, and some of it has been translated into English, and is available online.

- Sefer HaMa'amarim - a 29-volume set of Chasidic discourses, according to the years set. The most important of these include two three-year long cycle of discourses beginning "Yom Tov Shel Rosh Hashanah 5666 (Samech-Vov)" and "B'shaah Shehikdimu 5672 (Ayin-Beis)". They serve today as major in-depth encyclopedic introductory works into "oral" Chabad Chassidism (as opposed to the "written" one, i.e., Tanya) studied in Chabad yeshivas.

- Igros Kodesh - five volume set of letters

- Toras Sholom - compilation of public addresses

- Kuntres Uma'ayan - basic Chasidic text on self-transformation (as opposed to self-nullification as taught in Musar philosophy) and battling evil desires in an intellectual, Kabbalah-based way

- Kuntres HaTefillah - explanation of Chabad Chasidic prayer

- Kuntres HoAvodah - even more in-depth analysis of Chabad Chasidic prayer

- Maamar Veyadaata - To know G-d, explanation of the unity of G-d with the created Universe and how to reach the understanding and appreciation of it

- Maamar Heichaltzu - On Ahavas Yisroel, mystical aspects, sources and reasons for a love to a fellow Jew (and explanation of how exactly the dictum of loving one's fellow as oneself is the basis of all the Torah, including seemingly not related areas of it)

- Kuntres Eitz HaChayim - The Tree of Life -- essay on the importance of learning (how learning of Judaism can transform a Jew's life and personality and change his perception on his purpose in life), order of learning (for Chabad yeshivah students), and focus of Jewish learning.

- Chanoch Lana'ar - The Ethical Will

- Issa B'Midrash Tehillim - Bar Mitzvah Maamar -- mystical aspects of the commandment of tefillin; a Chasidic discourse usually recited at by a Chabad boy at his bar mitzvah

- Some of his published works in Hebrew

See also

Citations

- ↑ The Messiah of Brooklyn: Understanding Lubavitch Hasidim Past and Present, M. Avrum Ehrlich, Chapter 7

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Encyclopedia of Hasidism, entry: Schneersohn, Shalom Dovber. Naftali Lowenthal. Aronson, London 1996. ISBN 1-56821-123-6

- ↑ Letters from the Rashab to his cousin Rabbi Isaiah Berlin of Riga, dated 6-Tevet through 22-Iyar 5663

- ↑ Rabi Shalom Dovber Schneerson ztz”l - Tog News 3

- ↑ Rostov Celebrates the Rebbe Rashab's Birthday

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The Messiah of Brooklyn: Understanding Lubavitch Hasidim Past and Present, M. Avrum Ehrlich, Chapter 3

- ↑ Shemu'os Vesippurim, Refoel Kahn, vol. 1, pp. 144-145

- ↑ Shalom Goldman (2009). Zeal for Zion: Christians, Jews, and the Idea of the Promised Land. UNC Press Books. pp. 272–73. ISBN 978-0-8078-3344-5. Retrieved 9 May 2013. "The most eminent Orthodox rabbis of the first decade of the twentieth century, among them the Lubavitcher rebbe Sholom Dov Ber Schneersohn, issued powerful condemnations of political Zionism. Schneersohn, in 1903, warned that the Zionists "have made nationalism a substitute for the Torah and the commandments… After this assumption is accepted, anyone who enters the movement regards himself as no longer obliged to keep the commandments of the Torah, nor is there any hope consequently that at some time or another he will return, because, according to his own reckoning, he is a proper Jew in that he is a loyal nationalist."

- ↑ http://www.tog.co.il/en/Article.aspx?Id=488

- ↑

- ↑ The Four Worlds, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, Kehot, 2006, pp. 87-90. ISBN 0-8266-0462-5

- ↑ Yiras Hashem Otzaro,, Yisroel Alfenbein, Israel, 2005, p. 95.

External links

- Life timeline and published works

- A brief biography of Rabbi Sholom Dovber, the "Rebbe Rashab"

- The Rashab with Sigmund Freud

| Religious titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Shmuel Schneersohn |

Rebbe of Lubavitch 1892–1920 |

Succeeded by Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn |

|