Saka

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Tajikistan |

|---|

|

| Early history |

| Medieval history |

| Early modern history |

| Russian Vassalage |

| Soviet rule |

| Since independence |

| Timeline |

|

|

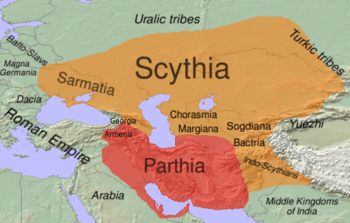

Approximate extent of East Iranian languages in the 1st century BC is shown in orange. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Unknown | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

Central Asia Pakistan Northern India | |

| Languages | |

| Scythian language Sakan language | |

| Religion | |

| Scythian religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Iranian peoples, Indo-Iranians |

The Saka (Old Persian Sakā; Sanskrit शाक Śāka; Greek Σάκαι; Latin Sacae; Old Chinese: *Sək) were a Scythian tribe or group of tribes of Iranian origin.[1] They were nomadic warriors roaming the steppes of modern-day Kazakhstan.

Greek and Latin texts suggest that the term Scythians referred to Iranian tribes from the much more extensive region of Scythia, which included parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia.[2][3]

Classical European and Persian accounts

B. N. Mukerjee has said that it is clear that ancient Greek and Roman scholars believed, all Sakai were Scythians, but not all Scythians were Sakai .[4]

Modern confusion about the identity of the Saka is partly due to the Persians. According to Herodotus, the Persians called all Scythians by the name Sakas.[5] Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus, AD 23–79) provides a more detailed explanation, stating that the Persians gave the name Sakai to the Scythian tribes "nearest to them".[6] The Scythians to the far north of Assyria were also called the Saka suni "Saka or Scythian sons" by the Persians. The Assyrians of the time of Esarhaddon record campaigning against a people they called in the Akkadian the Ashkuza or Ishhuza.[7] Hugo Winckler was the first to associate them with the Scyths which identification remains without serious question. They were closely associated with the Gimirrai,[7] who were the Cimmerians known to the ancient Greeks. Confusion arose because they were known to the Persians as Saka, however they were known to the Babylonians as Gimirrai, and both expressions are used synonymously on the trilingual Behistun inscription, carved in 515 BC on the order of Darius the Great.[8] These Scythians were mainly interested in settling in the kingdom of Urartu, which later became Armenia. The district of Shacusen, Uti Province, reflects their name.[9] In ancient Hebrew texts, the Ashkuz (Ashkenaz) are considered to be a direct offshoot from the Gimirri (Gomer).[10]

Thus the Behistun inscription mentions four divisions of Scythians,

- the Sakā paradraya "Saka beyond the sea" of Sarmatia,

- the Sakā tigraxaudā "Saka with pointy hats/caps",

- the Sakā haumavargā "haoma-drinking Saka"[11] (Amyrgians, the Saka tribe in closest proximity to Bactria and Sogdiana),

- the Sakā para Sugdam "Saka beyond Sugda (Sogdiana)" at the Jaxartes.

Of these, the Sakā tigraxaudā were the Saka proper.[citation needed] The Sakā paradraya were the western Scythians or Sarmatians, the Sakā haumavargā and Sakā para Sugdam were likely Scythian tribes associated with or split-of from the original Saka.[citation needed]

Ancient South Asian accounts

Pliny also mentions Aseni and Asoi clans south of the Hindukush.[12] Bucephala was the capital of the Aseni which stood on the Hydaspes (the Jhelum River).[13] The Sarauceans and Aseni are the Sacarauls and Asioi of Strabo.[14]

. Asio, Asi/Asii, Asva/Aswa, Ari-aspi, Aspasios, Aspasii (or Hippasii) are possibly variant names the classical writers have given to the horse-clans of the Kambojas.[15] The Old-Persian words for horse, "asa" and "aspa, have most likely been derived from this."[16]

If one accepts this connection, then the Tukharas (= Rishikas = Yuezhi) controlled the eastern parts of Bactria (Chinese Ta-hia) while the combined forces of the Sakarauloi, Asio (horse people = Parama Kambojas) and Pasinoi of Strabo occupied its western parts after being displaced from their original home in the Fergana valley by the Yuezhi. Ta-hia (Daxia) is then taken to mean the Tushara Kingdom which also included Badakshan, Chitral, Kafirstan and Wakhan[17] According to other scholars, it were the Saka hordes alone who had put an end to the Greek kingdom of Bactria.[18]

History

Migrations of the 2nd and 1st century BC have left traces in Sogdiana and Bactria, but they cannot firmly be attributed to the Saka, similarly with the sites of Sirkap and Taxila in Pakistan. The rich graves at Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan are seen as part of a population affected by the Saka.[19]

Indo-Scythians

Tadeusz Sulimirski notes that the Sacae also invaded parts of Northern India.[20] Weer Rajendra Rishi, and Indian linguist[21] has identified linguistic affinities between Indian and Central Asian languages, which further lends credence to the possibility of historical Sacae influence in Northern India.[20][22]

Kingdom of Khotan

Language

The language of the original Saka tribes is unknown. The only record from their early history is the Issyk inscription, a short fragment on a silver cup found in the Issyk kurgan, Kazakhstan.[citation needed]

The inscription is in a variant of the Kharoṣṭhī script, and is probably in a Saka dialect, constituting one of very few autochthonous epigraphic traces of that language. Harmatta (1999) identifies the language as Khotanese Saka, tentatively translating "The vessel should hold wine of grapes, added cooked food, so much, to the mortal, then added cooked fresh butter on".

What is nowadays called the Saka language is the language of the kingdom of Khotan which was ruled by the Saka. This was gradually conquered and acculturated by the Turkic expansion to Central Asia beginning in the 4th century. The only known remnants of the Khotanese Saka language come from Xinjiang, China. The language there is widely divergent from the rest of Iranian belongs to the Eastern Iranian group. It also is divided into two divergent dialects. Both dialects share features with modern Wakhi and Pashto, but both of the Saka dialects contain many borrowings from the Middle Indo-Aryan Prakrit.[23]

See also

- Saka era

- Saka calendar

- Saka language

- Saka Kingdom

Notes

- ↑ P. Lurje, “Yārkand”, Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society ... – Google Books. 2007-04-06. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland By Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland-page-323

- ↑ B. N. Mukerjee, Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 690-91.

- ↑ Herodotus Book VII, 64

- ↑ Naturalis Historia, VI, 19, 50

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Westermann, Claus; John J. Scullion, Translator (1984). : A Continental Commentary. Minneapolis. p. 506. ISBN 0800695003.

- ↑ George Rawlinson, noted in his translation of History of Herodotus, Book VII, p. 378

- ↑ Kurkjian, Vahan M. (1964). A History of Armenia. New York: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America. p. 23.

- ↑ "The sons of Gomer were Ashkenaz, Riphath,[a] and Togarmah." See also the entry for Ashkenaz in Young, Robert. Analytical Concordance to the Bible. McLean, Virginia: Mac Donald Publishing Company. ISBN 0-917006-29-1.

- ↑ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/haumavarga

- ↑ Pliny: Hist Nat., VI.21.8–23.11, List of Indian races

- ↑ Alexander the Great, Sources and Studies, p 236, W. W. Tarn; Political History of Indian People, 1996, p 232, H. C. Raychaudhury, B. N. Mukerjee

- ↑ History and Culture of Indian People, Age of Imperial Unity, p 111; Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 692.

- ↑ For nomenclature Aspasii, Hipasii, see: Olaf Caroe, The Pathans, 1958, pp 37, 55–56. Pliny also refers to horse clans like Aseni, Asoi living in north-west of India (which were none-else than the Ashvayana and Ashvakayana Kambojas of Indian texts). See: Hist. Nat. VI 21.8–23.11; See Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian, Trans. and edited by J. W. McCrindle, Calcutta and Bombay,: Thacker, Spink, 1877, 30–174.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Iranica Article on Asb

- ↑ Political History of Ancient India, 1996, Commentary, p 719, B. N. Mukerjee. Cf: "It appears likely that like the Yue-chis, the Scythians had also occupied a part of Transoxiana before conquering Bactria. If the Tokhario, who were the same as or affiliated with Yue-chihs, and who were mistaken as Scythian people, participated in the same series of invasions of Bactria of the Greeks, then it may be inferred that eastern Bactria was conquered by Yue-chis and the western by other nomadic people in about the same period. In other words, the Greek rule in Bactria was put to end in c 130/29 BC due to invasion by the Great Yue-chis and the Scythians Sakas nomads (Commentary: Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 692-93, B.N. Mukerjee). It is notable that before its occupation by Tukhara Yue-chis, Badakashan formed a part of ancient Kamboja i.e. Parama Kamboja country. But after its occupation by the Tukharas in the 2nd century BC, it became a part of Tukharistan. Around the 4th or 5th century, when the fortunes of the Tukharas finally died down, the original population of Kambojas re-asserted itself and the region again started to be called by its ancient name Kamboja (See: Bhartya Itihaas ki Ruprekha, p 534, J.C. Vidyalankar; Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, pp 129, 300 J.L. Kamboj; Kambojas Through the Ages, 2005, p 159, S Kirpal Singh). There are several later-time references to this Kamboja of Pamirs/Badakshan. Raghuvamsha, a 5th c Sanskrit play by Kalidasa, attests their presence on river Vamkshu (Oxus) as neighbors to the Hunas (4.68–70). They have also been attested as Kiumito by 7th-century Chinese pilgrim Hiun Tsang. King Lalitadiya of Kashmir in the 8th century, had invaded the Oxian Kambojas as is attested by Rajatarangini of Kalhana (See: Rajatarangini 4.163-65). Here they are mentioned as living in the eastern parts of the Oxus valley as neighbors to the Tukharas who were living in western parts of Oxus valley (See: The Land of the Kambojas, Purana, Vol V, No, July 1962, p 250, D. C. Sircar). These Kambojas apparently were descendants of that section of the Kambojas who, instead of leaving their ancestral land during second c BC under assault from Ta Yue-chi, had compromised with the invaders and had decided to stay put in their ancestral land instead of moving to Helmond valley or to the Kabol valley. There are other references which equate Kamboja= Tokhara. A Buddhist Sanskrit Vinaya text (N. Dutt, Gilgit Manuscripts, III, 3, 136, quoted in B.S.O.A.S XIII, 404) has the expression satam Kambojikanam kanayanam i.e a hundred maidens from Kamboja. This has been rendered in Tibetan as Tho-gar yul-gyi bu-mo brgya and in Mongolian as Togar ulus-un yagun ükin. Thus Kamboja has been rendered as Tho-gar or Togar. And Tho-gar/Togar is Tibetan/Mongolian names for Tokhar/Tukhar. See refs: Irano-Indica III, H. W. Bailey, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 13, No. 2, 1950, pp. 389–409; see also: Ancient Kamboja, Iran and Islam, 1971, p 66, H. W. Bailey.

- ↑ Cambridge History of India, Vol I, p 510; Taxila, Vol I, p 24, Marshal, Early History of North India, p 50, S. Chattopadhyava.

- ↑ Yaroslav Lebedynsky, P. 84

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Sulimirski, Tadeusz (1970). The Sarmatians. Volume 73 of Ancient peoples and places. New York: Praeger. pp. 113–114. "The evidence of both the ancient authors and the archaeological remains point to a massive migration of Sacian (Sakas)/Massagetan tribes from the Syr Daria Delta (Central Asia) by the middle of the second century B.C. Some of the Syr Darian tribes; they also invaded North India."

- ↑ Indian Institute of Romani Studies

- ↑ Rishi, Weer Rajendra (1982). India & Russia: linguistic & cultural affinity. Roma. p. 95.

- ↑ Litvinsky, Boris Abramovich; Vorobyova-Desyatovskaya, M.I (1999). "Religions and religious movements". History of civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 421–448. ISBN 8120815408.

References

- Bailey, H. W. 1958. "Languages of the Saka." Handbuch der Orientalistik, I. Abt., 4. Bd., I. Absch., Leiden-Köln. 1958.

- Bailey, H. W. (1979). Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge University Press. 1979. 1st Paperback edition 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-14250-2.

- Davis-Kimball, Jeannine. 2002. Warrior Women: An Archaeologist's Search for History's Hidden Heroines. Warner Books, New York. 1st Trade printing, 2003. ISBN 0-446-67983-6 (pbk).

- Bulletin of the Asia Institute: The Archaeology and Art of Central Asia. Studies From the Former Soviet Union. New Series. Edited by B. A. Litvinskii and Carol Altman Bromberg. Translation directed by Mary Fleming Zirin. Vol. 8, (1994), pp. 37–46.

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. John E. Hill. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.

- Lebedynsky, Iaroslav. (2006). Les Saces: Les <<Scythes>> d'Asie, VIIIe av. J.-C.-IVe siècle apr. J.-C. Editions Errance, Paris. ISBN 2-87772-337-2 (in French).

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. 1970. "The Wu-sun and Sakas and the Yüeh-chih Migration." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 33 (1970), pp. 154–160.

- Puri, B. N. 1994. "The Sakas and Indo-Parthians." In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 191–207.

- Thomas, F. W. 1906. "Sakastana." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1906), pp. 181–216.

- Yu, Taishan. 1998. A Study of Saka History. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 80. July, 1998. Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania.

- Yu, Taishan. 2000. A Hypothesis about the Source of the Sai Tribes. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 106. September, 2000. Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania.

External links

- Scythians/Sacae by Jona Lendering

- Article by Kivisild et al. on genetic heritage of early Indian settlers

- [http://boole.cs.iastate.edu/book/3-%CA%B7(%C0%FA%CA%B7)/3-%CA%C0%BD%E7%C0%FA%CA%B7/www.friesian.com/sangoku.htm#saka, Indian, Japanese and Chinese Emperors]

| ||||||||||