Semigroup

In mathematics, a semigroup is an algebraic structure consisting of a set together with an associative binary operation. A semigroup generalizes a monoid in that a semigroup need not have an identity element. It also (originally) generalized a group (a monoid with all inverses) to a type where every element did not have to have an inverse, thus the name semigroup.

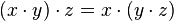

The binary operation of a semigroup is most often denoted multiplicatively:  , or simply

, or simply  , denotes the result of applying the semigroup operation to the ordered pair

, denotes the result of applying the semigroup operation to the ordered pair  . The operation is required to be associative so that

. The operation is required to be associative so that  for all x, y and z, but need not be commutative so that

for all x, y and z, but need not be commutative so that  does not have to equal

does not have to equal  (contrast to the standard multiplication operator on real numbers, where xy = yx).

(contrast to the standard multiplication operator on real numbers, where xy = yx).

By definition, a semigroup is an associative magma. A semigroup with an identity element is called a monoid. A group is then a monoid in which every element has an inverse element. Semigroups must not be confused with quasigroups which are sets with a not necessarily associative binary operation such that division is always possible.

The formal study of semigroups began in the early 20th century. Semigroups are important in many areas of mathematics because they are the abstract algebraic underpinning of "memoryless" systems: time-dependent systems that start from scratch at each iteration. In applied mathematics, semigroups are fundamental models for linear time-invariant systems. In partial differential equations, a semigroup is associated to any equation whose spatial evolution is independent of time. The theory of finite semigroups has been of particular importance in theoretical computer science since the 1950s because of the natural link between finite semigroups and finite automata. In probability theory, semigroups are associated with Markov processes (Feller 1971).

| Algebraic structures |

|---|

|

Group-like |

|

Ring-like |

Definition

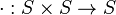

A semigroup is a set  together with a binary operation "

together with a binary operation " " (that is, a function

" (that is, a function  ) that satisfies the associative property:

) that satisfies the associative property:

For all  , the equation

, the equation  holds.

holds.

More succinctly, a semigroup is an associative magma.

Examples of semigroups

- Empty semigroup: the empty set forms a semigroup with the empty function as the binary operation.

- Semigroup with one element: there is essentially just one, the singleton {a} with operation a · a = a.

- Semigroup with two elements: there are five which are essentially different.

- The set of positive integers with addition.

- Square nonnegative matrices of a given size with matrix multiplication.

- Any ideal of a ring with the multiplication of the ring.

- The set of all finite strings over a fixed alphabet Σ with concatenation of strings as the semigroup operation — the so-called "free semigroup over Σ". With the empty string included, this semigroup becomes the free monoid over Σ.

- A probability distribution F together with all convolution powers of F, with convolution as the operation. This is called a convolution semigroup.

- A monoid is a semigroup with an identity element.

- A group is a monoid in which every element has an inverse element.

- Transformation semigroups and monoids

- The set of continuous functions from a topological space to itself

Basic concepts

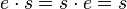

Identity and zero

Every semigroup, in fact every magma, has at most one identity element. A semigroup with identity is called a monoid. A semigroup without identity may be embedded into a monoid simply by adjoining an element  to

to  and defining

and defining  for all

for all  .[1][2] The notation S1 denotes a monoid obtained from S by adjoining an identity if necessary (S1 = S for a monoid).[2]

.[1][2] The notation S1 denotes a monoid obtained from S by adjoining an identity if necessary (S1 = S for a monoid).[2]

Similarly, every magma has at most one absorbing element, which in semigroup theory is called a zero. Analogous to the above construction, for every semigroup S, one defines S0, a semigroup with 0 that embeds S.

Subsemigroups and ideals

The semigroup operation induces an operation on the collection of its subsets: given subsets A and B of a semigroup S, their product A*B, written commonly as AB, is the set { ab | a in A and b in B }. In terms of this operations, a subset A is called

- a subsemigroup if AA is a subset of A,

- a right ideal if AS is a subset of A, and

- a left ideal if SA is a subset of A.

If A is both a left ideal and a right ideal then it is called an ideal (or a two-sided ideal).

If S is a semigroup, then the intersection of any collection of subsemigroups of S is also a subsemigroup of S. So the subsemigroups of S form a complete lattice.

An example of semigroup with no minimal ideal is the set of positive integers under addition. The minimal ideal of a commutative semigroup, when it exists, is a group.

Green's relations, a set of five equivalence relations that characterise the elements in terms of the principal ideals they generate, are important tools for analysing the ideals of a semigroup and related notions of structure.

Homomorphisms and congruences

A semigroup homomorphism is a function that preserves semigroup structure. A function f: S → T between two semigroups is a homomorphism if the equation

- f(ab) = f(a)f(b).

holds for all elements a, b in S, i.e. the result is the same when performing the semigroup operation after or before applying the map f.

A semigroup homomorphism between monoids preserves identity if it is a monoid homomorphism. But there are semigroup homomorphisms which are not monoid homomorphisms, e.g. the canonical embedding of a semigroup  without identity into

without identity into  . Conditions characterizing monoid homomorphisms are discussed further. Let

. Conditions characterizing monoid homomorphisms are discussed further. Let  be a semigroup homomorphism. The image of

be a semigroup homomorphism. The image of  is also a semigroup. If

is also a semigroup. If  is a monoid with an identity element

is a monoid with an identity element  , then

, then  is the identity element in the image of

is the identity element in the image of  . If

. If  is also a monoid with an identity element

is also a monoid with an identity element  and

and  belongs to the image of

belongs to the image of  , then

, then  , i.e.

, i.e.  is a monoid homomorphism. Particularly, if

is a monoid homomorphism. Particularly, if  is surjective, then it is a monoid homomorphism.

is surjective, then it is a monoid homomorphism.

Two semigroups S and T are said to be isomorphic if there is a bijection f : S ↔ T with the property that, for any elements a, b in S, f(ab) = f(a)f(b). Isomorphic semigroups have the same structure.

A semigroup congruence  is an equivalence relation that is compatible with the semigroup operation. That is, a subset

is an equivalence relation that is compatible with the semigroup operation. That is, a subset  that is an equivalence relation and

that is an equivalence relation and  and

and  implies

implies  for every

for every  in S. Like any equivalence relation, a semigroup congruence

in S. Like any equivalence relation, a semigroup congruence  induces congruence classes

induces congruence classes

and the semigroup operation induces a binary operation  on the congruence classes:

on the congruence classes:

Because  is a congruence, the set of all congruence classes of

is a congruence, the set of all congruence classes of  forms a semigroup with

forms a semigroup with  , called the quotient semigroup or factor semigroup, and denoted

, called the quotient semigroup or factor semigroup, and denoted  . The mapping

. The mapping ![x\mapsto [x]_{\sim }](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/7/7/3/2773abb6419258def4152add809cc3a1.png) is a semigroup homomorphism, called the quotient map, canonical surjection or projection; if S is a monoid then quotient semigroup is a monoid with identity

is a semigroup homomorphism, called the quotient map, canonical surjection or projection; if S is a monoid then quotient semigroup is a monoid with identity ![[1]_{\sim }](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/d/5/1/c/d51c9f6dcc0d7d99c8436ecb535a0d82.png) . Conversely, the kernel of any semigroup homomorphism is a semigroup congruence. These results are nothing more than a particularization of the first isomorphism theorem in universal algebra. Congruence classes and factor monoids are the objects of study in string rewriting systems.

. Conversely, the kernel of any semigroup homomorphism is a semigroup congruence. These results are nothing more than a particularization of the first isomorphism theorem in universal algebra. Congruence classes and factor monoids are the objects of study in string rewriting systems.

A nuclear congruence on S is one which is the kernel of an endomorphism of S.[3]

A semigroup S satisfies the maximal condition on congruences if any family of congruences on S, ordered by inclusion, has a maximal element. By Zorn's lemma, this is equivalent to saying that the ascending chain condition holds: there is no infinite strictly ascending chain of congruences on S.[4]

Every ideal I of a semigroup induces a subsemigroup, the Rees factor semigroup via the congruence x ρ y ⇔ either x = y or both x and y are in I.

Structure of semigroups

For any subset A of S there is a smallest subsemigroup T of S which contains A, and we say that A generates T. A single element x of S generates the subsemigroup { xn | n is a positive integer }. If this is finite, then x is said to be of finite order, otherwise it is of infinite order. A semigroup is said to be periodic if all of its elements are of finite order. A semigroup generated by a single element is said to be monogenic (or cyclic). If a monogenic semigroup is infinite then it is isomorphic to the semigroup of positive integers with the operation of addition. If it is finite and nonempty, then it must contain at least one idempotent. It follows that every nonempty periodic semigroup has at least one idempotent.

A subsemigroup which is also a group is called a subgroup. There is a close relationship between the subgroups of a semigroup and its idempotents. Each subgroup contains exactly one idempotent, namely the identity element of the subgroup. For each idempotent e of the semigroup there is a unique maximal subgroup containing e. Each maximal subgroup arises in this way, so there is a one-to-one correspondence between idempotents and maximal subgroups. Here the term maximal subgroup differs from its standard use in group theory.

More can often be said when the order is finite. For example, every nonempty finite semigroup is periodic, and has a minimal ideal and at least one idempotent. For more on the structure of finite semigroups, see Krohn–Rhodes theory.

Special classes of semigroups

- A monoid is a semigroup with identity.

- A subsemigroup is a subset of a semigroup that is closed under the semigroup operation.

- A band is a semigroup the operation of which is idempotent.

- A cancellative semigroup is one having the cancellation property:[5] a · b = a · c implies b = c and similarly for b · a = c · a.

- A semilattice is a semigroup whose operation is idempotent and commutative.

- 0-simple semigroups.

- Transformation semigroups: any finite semigroup S can be represented by transformations of a (state-) set Q of at most |S|+1 states. Each element x of S then maps Q into itself x: Q → Q and sequence xy is defined by q(xy) = (qx)y for each q in Q. Sequencing clearly is an associative operation, here equivalent to function composition. This representation is basic for any automaton or finite state machine (FSM).

- The bicyclic semigroup is in fact a monoid, which can be described as the free semigroup on two generators p and q, under the relation p q = 1.

- C0-semigroups.

- Regular semigroups. Every element x has at least one inverse y satisfying xyx=x and yxy=y; the elements x and y are sometimes called "mutually inverse".

- Inverse semigroups are regular semigroups where every element has exactly one inverse. Alternatively, a regular semigroup is inverse if and only if any two idempotents commute.

- Affine semigroup: a semigroup that is isomorphic to a finitely-generated subsemigroup of Zd. These semigroups have applications to commutative algebra.

Group of fractions

The group of fractions of a semigroup S is the group G = G(S) generated by the elements of S as generators and all equations xy=z which hold true in S as relations.[6] This has a universal property for morphisms from S to a group.[7] There is an obvious map from S to G(S) by sending each element of S to the corresponding generator.

An important question is to characterize those semigroups for which this map is an embedding. This need not always be the case: for example, take S to be the semigroup of subsets of some set X with set-theoretic intersection as the binary operation (this is an example of a semilattice). Since A.A = A holds for all elements of S, this must be true for all generators of G(S) as well: which is therefore the trivial group. It is clearly necessary for embeddability that S have the cancellation property. When S is commutative this condition is also sufficient[8] and the Grothendieck group of the semigroup provides a construction of the group of fractions. The problem for non-commutative semigroups can be traced to the first substantial paper on semigroups, (Suschkewitsch 1928).[9] Anatoly Maltsev gave necessary and conditions for embeddability in 1937.[10]

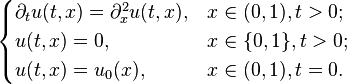

Semigroup methods in partial differential equations

Semigroup theory can be used to study some problems in the field of partial differential equations. Roughly speaking, the semigroup approach is to regard a time-dependent partial differential equation as an ordinary differential equation on a function space. For example, consider the following initial/boundary value problem for the heat equation on the spatial interval (0, 1) ⊂ R and times t ≥ 0:

Let X be the Lp space L2((0, 1); R) and let A be the second-derivative operator with domain

Then the above initial/boundary value problem can be interpreted as an initial value problem for an ordinary differential equation on the space X:

On an heuristic level, the solution to this problem "ought" to be u(t) = exp(tA)u0. However, for a rigorous treatment, a meaning must be given to the exponential of tA. As a function of t, exp(tA) is a semigroup of operators from X to itself, taking the initial state u0 at time t = 0 to the state u(t) = exp(tA)u0 at time t. The operator A is said to be the infinitesimal generator of the semigroup.

History

The study of semigroups trailed behind that of other algebraic structures with more complex axioms such as groups or rings. A number of sources[11][12] attribute the first use of the term (in French) to J.-A. de Séguier in Élements de la Théorie des Groupes Abstraits (Elements of the Theory of Abstract Groups) in 1904. The term is used in English in 1908 in Harold Hinton's Theory of Groups of Finite Order.

Anton Suschkewitsch obtained the first non-trivial results about semigroups. His 1928 paper Über die endlichen Gruppen ohne das Gesetz der eindeutigen Umkehrbarkeit (On finite groups without the rule of unique invertibility) determined the structure of finite simple semigroups and showed that the minimal ideal (or Green's relations J-class) of a finite semigroup is simple.[12] From that point on, the foundations of semigroup theory were further laid by David Rees, James Alexander Green, Evgenii Sergeevich Lyapin, Alfred H. Clifford and Gordon Preston. The latter two published a two-volume monograph on semigroup theory in 1961 and 1967 respectively. In 1970, a new periodical called Semigroup Forum (currently edited by Springer Verlag) became one of the few mathematical journals devoted entirely to semigroup theory.

In recent years researchers in the field have become more specialized with dedicated monographs appearing on important classes of semigroups, like inverse semigroups, as well as monographs focusing on applications in algebraic automata theory, particularly for finite automata, and also in functional analysis.

Generalizations

| Group-like structures | |||||

| Totality* | Associativity | Identity | Inverses | Commutativity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magma | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Semigroup | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Monoid | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Group | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Abelian Group | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Loop | Yes | No | Yes | Yes** | No |

| Quasigroup | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Groupoid | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Category | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Semicategory | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| *Closure, which is used in many sources to define group-like structures, is an equivalent axiom to totality, though defined differently. | |||||

| **Each element of a loop has a left and right inverse, but these need not coincide. | |||||

If the associativity axiom of a semigroup is dropped, the result is a magma, which is nothing more than a set M equipped with a binary operation M × M → M.

Generalizing in a different direction, an n-ary semigroup (also n-semigroup, polyadic semigroup or multiary semigroup) is a generalization of a semigroup to a set G with a n-ary operation instead of a binary operation.[13] The associative law is generalized as follows: ternary associativity is (abc)de = a(bcd)e = ab(cde), i.e. the string abcde with any three adjacent elements bracketed. N-ary associativity is a string of length n + (n − 1) with any n adjacent elements bracketed. A 2-ary semigroup is just a semigroup. Further axioms lead to an n-ary group.

A third generalization is the semigroupoid, in which the requirement that the binary relation be total is lifted. As categories generalize monoids in the same way, a semigroupoid behaves much like a category but lacks identities.

See also

- Absorbing element

- Biordered set

- Empty semigroup

- Identity element

- Light's associativity test

- Semigroup ring

- Weak inverse

Notes

- ↑ Jacobson (2009), p. 30, ex. 5

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lawson (1998), p. 20

- ↑ Lothaire (2011) p.463

- ↑ Lothaire (2011) p.465

- ↑ (Clifford & Preston 1967, p. 3)

- ↑ B. Farb, Problems on mapping class groups and related topics (Amer. Math. Soc., 2006) page 357. ISBN 0-8218-3838-5

- ↑ M. Auslander and D.A. Buchsbaum, Groups, rings, modules (Harper&Row, 1974) page 50. ISBN 0-06-040387-X

- ↑ (Clifford & Preston 1961, p. 34)

- ↑ G. B. Preston (1990). "Personal reminiscences of the early history of semigroups". Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ↑ Maltsev, A. (1937), "On the immersion of an algebraic ring into a field", Math. Annalen 113: 686–691, doi:10.1007/BF01571659.

- ↑ Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 An account of Suschkewitsch's paper by Christopher Hollings

- ↑ Dudek, W.A. (2001), "On some old problems in n-ary groups", Quasigroups and Related Systems 8: 15–36

References

- General references

- Howie, John M. (1995), Fundamentals of Semigroup Theory, Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-19-851194-9.

- Clifford, A. H.; Preston, G. B. (1961), The algebraic theory of semigroups, volume 1, American Mathematical Society.

- Clifford, A. H.; Preston, G. B. (1967), The algebraic theory of semigroups, volume 2, American Mathematical Society.

- Grillet, Pierre Antoine (1995), Semigroups: an introduction to the structure theory, Marcel Dekker, Inc.

- Specific references

- Feller, William (1971), An introduction to probability theory and its applications. Vol. II., Second edition, New York: John Wiley & Sons, MR 0270403.

- Hille, Einar; Phillips, Ralph S. (1974), Functional analysis and semi-groups, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, MR 0423094.

- Suschkewitsch, Anton (1928), "Über die endlichen Gruppen ohne das Gesetz der eindeutigen Umkehrbarkeit", Mathematische Annalen 99 (1): 30–50, doi:10.1007/BF01459084, ISSN 0025-5831, MR 1512437.

- Kantorovitz, Shmuel (2010), Topics in Operator Semigroups., Boston, MA: Birkhauser.

- Jacobson, Nathan (2009), Basic algebra 1 (2nd ed.), Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-47189-1

- Lawson, M.V. (1998), Inverse semigroups: the theory of partial symmetries, World Scientific, ISBN 978-981-02-3316-7

- Lothaire, M. (2011), Algebraic combinatorics on words, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications 90, With preface by Jean Berstel and Dominique Perrin (Reprint of the 2002 hardback ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-18071-9, Zbl 1221.68183

![[a]_{\sim }=\{x\in S\vert \;x\sim a\}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/0/8/9/5/089577c3711acba08f50b99d9d366687.png)

![[u]_{\sim }\circ [v]_{\sim }=[uv]_{\sim }](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/a/d/b/c/adbc8398016c1c97899ffbe2a37b0c64.png)