Sea serpent

| (Various) | |

|---|---|

A sea serpent from Olaus Magnus's book History of the Northern Peoples (1555). | |

| Grouping | Legendary Creature |

| Sub grouping | Sea monster |

| Country | Various |

| Habitat | Sea |

A sea serpent or sea dragon is a type of sea monster either wholly or partly serpentine.

Sightings of sea serpents have been reported for hundreds of years, and continue to be claimed today. Cryptozoologist Bruce Champagne identified more than 1,200 purported sea serpent sightings.[1] It is currently believed that the sightings can be best explained as known animals such as oarfish, whales, or sharks (in particular, the frilled shark).[2] Some cryptozoologists have suggested that the sea serpents are relict plesiosaurs, mosasaurs or other Mesozoic marine reptiles, an idea often associated with lake monsters such as the Loch Ness Monster.

In mythology

In Norse mythology, Jörmungandr, or "Midgarðsormr" was a sea serpent so long that it encircled the entire world, Midgard. Some stories report of sailors mistaking its back for a chain of islands. Sea serpents also appear frequently in later Scandinavian folklore, particularly in that of Norway.[3][4]

In 1028 AD, Saint Olaf is said to have killed a sea serpent in Valldal, Norway, throwing its body onto the mountain Syltefjellet. Marks on the mountain are associated with the legend.[5][6] In Swedish ecclesiastic and writer Olaus Magnus's Carta marina, many marine monsters of varied form, including an immense sea serpent, appear. Moreover, in his 1555 work History of the Northern Peoples, Magnus gives the following description of a Norwegian sea serpent:

| “ | Those who sail up along the coast of Norway to trade or to fish, all tell the remarkable story of how a serpent of fearsome size, 200 feet long and 20 feet wide, resides in rifts and caves outside Bergen. On bright summer nights this serpent leaves the caves to eat calves, lambs and pigs, or it fares out to the sea and feeds on sea nettles, crabs and similar marine animals. It has ell-long hair hanging from its neck, sharp black scales and flaming red eyes. It attacks vessels, grabs and swallows people, as it lifts itself up like a column from the water.[7][8] | ” |

Sea serpents were known to seafaring cultures in the Mediterranean and Near East, appearing in both mythology (the Babylonian Labbu) and in apparent eye-witness accounts (Aristotle's Historia Animalium). In the Aeneid, a pair of sea serpents killed Laocoön and his sons when Laocoön argued against bringing the Trojan Horse into Troy.

In the Bible

The Bible refers to Leviathan and Rahab, from the Hebrew Tanakh, although 'great creatures of the sea' (NIV) are also mentioned in Book of Genesis 1:21. In the Book of Amos 9:3 speaks of a serpent to bite the people who try to hide in the sea from God.

Notable cases

Hans Egede, the national saint of Greenland, gives an 18th-century descriptions of a sea serpent. On 6 July 1734 his ship sailed past the coast of Greenland when suddenly those on board

| “ | saw a most terrible creature, resembling nothing they saw before. The monster lifted its head so high that it seemed to be higher than the crow's nest on the mainmast. The head was small and the body short and wrinkled. The unknown creature was using giant fins which propelled it through the water. Later the sailors saw its tail as well. The monster was longer than our whole ship, wrote Egede. (Mareš, 1997) | ” |

Sea serpent sightings on the coast of New England, are documented beginning in 1638. An incident in August 1817 spawned a rather silly mix-up when a committee of the Linnaean Society of New England went so far as to give a deformed terrestrial snake the name Scoliophis atlanticus, believing it was the juvenile form of a sea serpent that had recently been reported in Gloucester Harbor.[9] The Gloucester Harbor serpent was claimed to have been seen by hundreds of New England residents, including the crews of four whaling boats that reportedly sought out the serpent in the harbor.[10] Rife with political undertones, the serpent was known in the harbor region as "Embargo."[10] Sworn statements made before a local Justice of the Peace and first published in 1818 were never recanted.[11] After the Linnaean Society's misidentification was discovered, it was frequently cited by debunkers as evidence that the creature did not exist.

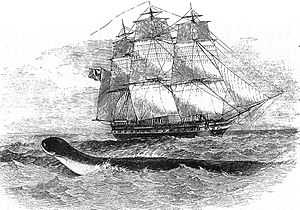

A particularly famous sea serpent sighting was made by the men and officers of HMS Daedalus in August 1848 during a voyage to Saint Helena in the South Atlantic; the creature they saw, some 60 feet (18 m) long, held a peculiar maned head above the water. The sighting caused quite a stir in the London papers, and Sir Richard Owen, the famous English biologist, proclaimed the beast an elephant seal. Other explanations for the sighting proposed that it was actually an upside-down canoe, or a posing giant squid.[12]

Another sighting took place in 1905 off the coast of Brazil. The crew of the Valhalla and two naturalists, Michael J. Nicoll and E. G. B. Meade-Waldo, saw a long-necked, turtle headed creature, with a large dorsal fin. Based on its dorsal fin and the shape of its head, some (such as Bernard Heuvelmans) have suggested that the animal was some sort of marine mammal. A skeptical suggestion is that the sighting was of a posing giant squid, but this is hard to accept given that squids do not swim with their fins or arms protruding from the water.

On April 25, 1977, the Japanese trawler Zuiyo Maru, sailing east of Christchurch, New Zealand, caught a strange, unknown creature in the trawl. Photographs and tissue specimens were taken. While initially identified as a prehistoric plesiosaur, analysis later indicated that the body was the carcass of a basking shark.

Misidentifications

Skeptics and debunkers have questioned the interpretation of sea serpent sightings, suggesting that reports of serpents are misidentifications of things such as cetaceans (whales and dolphins), sea snakes, eels, basking sharks, frilled sharks, baleen whales, oarfish, large pinnipeds, seaweed, driftwood, flocks of birds, and giant squid.

While most cryptozoologists recognize that at least some reports are simple misidentifications, they claim that many of the creatures described by those who have seen them look nothing like the known species put forward by skeptics and claim that certain reports stick out. For their part, the skeptics remain unconvinced, pointing out that even in the absence of outright hoaxes, imagination has a way of twisting and inflating the slightly out-of-the-ordinary until it becomes extraordinary.

A recent posting on the Centre of Fortean Zoology blog by Cryptozoologist Dale Drinnon notes his check of the categories in Heuvelmans' In The Wake of the Sea-Serpents, in which he extracted the mistaken observation categories as a control to check the Sea-serpent categories by using the reports he created identikits for the mistaken observations and enlarged them to possibly 126 of Heuvelmans' sightings, making the mistaken observations the largest section of Heuvelmans' reports. His identikits include oarfish, basking sharks, toothed whales, baleen whales, lines of large whales for the largest Sea-serpent "hump" sightings and trains of smaller cetaceans for the "Many-finned,elephant seals and manta rays. Each of these categories was given a percentage of the whole body of reports, ranging between 1% and 5% with the whales at an average 2.5%, figures which he considers comparable to the regular Sea-serpent categories of Super-eel and Marine Saurian (each of which he breaks into a larger and a smaller sized series following Heuvelmans' suggestion in In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents) [13] Drinnon has also published in the 2010 CFZ yearbook [14] in which he modifies Coleman's categories (below), adding a possible Giant otter category to the Giant Beavers and modifying several others, bringing the total to 17 categories to broaden the coverage. The broadened coverage allows more instances of conventional fishes such as sturgeons and catfishes, left off Coleman's list. In a separate and earlier CFZ blog, Drinnon reviewed Bruce Champagne's sea-serpent categories and identified several of them as known animals, and several whales in particular [15] Drinnon basically recognises the Longneck, Marine Saurian and Super-eel categories in this blog as well, with the modification that the Marine Saurian as spoken of by Champagne is more likely a large crocodile akin to the saltwater crocodile that there has been a suggestion that an eel-like animal is involved in certain "Many-finned" observations. The whale categories he identifies are: BC 2A-Possible Odobenocetops, BC2B, Atlantic gray whale or Scrag Whale, BC 4B, as being similar to an unidentified large-finned beaked whale otherwise reported in the Pacific, and BC 5, the large Father-of-All-the-Turtles, as a humpback whale turned turtle.

Classification systems

Cryptozoologists have argued for the existence of sea serpents by claiming that people report seeing similar things, and further arguing that it is possible to classify sightings into different "types". There have been different classification attempts with different results, although they share some common characteristics.

Anthonie Cornelis Oudemans

- Megophias megophias : A large sea lion-like creature with a long neck and long tail. Over 200 feet (61 m) long. Only the male has a mane. It is cosmopolitan.

Bernard Heuvelmans

- Long Necked or Megalotaria longicollis: A 60-foot (18 m), long-necked, short-tailed sea lion. Hair and whiskers reported. Cosmopolitan.

- Merhorse or Halshippus olai-magni: A 60-foot (18 m), medium-necked, large-eyed, horse-headed pinniped. Often has whiskers. It is also cosmopolitan.

- Many-Humped or Plurigibbosus novae-angliae: A 60–100-foot (18–30 m), medium-necked, long-bodied archaeocete. It has a series of humps or a crest on the spine like a sperm whale's or grey whale's. It only lives in the North Atlantic.

- Super Otter or Hyperhydra egedei: A 65–100-foot (20–30 m), medium-necked, long-bodied archaeocete that resembles an otter. It moves in numerous vertical undulations (6-7). Lived near Norway and Greenland, and presumed to be extinct by Heuvelmans.

- Many Finned or Cetioscolopendra aeliani: A 60–70-foot (18–21 m), short necked archeocete. It has a number of lateral projections that look like dorsal fins, but turned the incorrect way. Compare to the armor on Desmatosuchus, but much more prominent.

- Super Eels: A group of large and possibly unrelated eels. Partially based on the Leptocephalus giganteus larvae, later shown to be normal sized. [This is a controversial identification of a larval specimen made without benefit of actually examining the specimen. This "identification" was done by the paperwork and the actual specimen was missing by then.] Heuvelmans theorized eel, synbranchid, and elasmobranch identities as being possible. Cosmopolitan.

- Marine Saurian: A 50–60-foot (15–18 m) crocodile, or crocodile-like animal (Mosasaur, Pliosaur, etc.)

- Yellow Belly: A very large, 100–200-foot (30–61 m) yellow-and-black-striped, tadpole-shaped creature. Dropped.

- Father-of-all-the-turtles: A giant turtle. Dropped.

- Giant Invertebrates: Giant Venus's girdle and salp colonies. Added. It is not clear if Heuvelmans intended them to be unknown species or extreme forms of known species.

Loren Coleman and Patrick Huyghe

- Classic Sea Serpent: A quadrupedal, elongated animal with the appearance of many humps when swimming. Essentially a composite of the many humped, super otter, and super eels types. The authors suggest Basilosaurus as a candidate, or possibly Remingtoncetids.

- Waterhorse: A large pinniped, similar to the long necked and merhorse. Only the males are maned, but females appear to have snorkels. Both of their eyes are rather small. They are noteworthy for being behind both salt and fresh water sightings.

- Mystery Cetacean: A category of unknown whale species including double finned whales and dolphins, dorsal finned sperm whales, unknown beaked whales, an unknown orca, and others.

- Giant Shark: A surviving megalodon.

- Mystery Manta: A small manta ray with dorsal markings.

- Great Sea Centipede: Same as the many finned. The authors suggest the flippers may either be retractile, and the "scaly" appearance could be caused by parasites.

- Mystery Saurian: Same as the marine saurian.

- Cryptic Chelonian: A resurrection of the father-of-all-turtles.

- Mystery Sirenian: Late surviving Steller's Sea Cow.

- Giant Octopus, Octopus giganteus or Otoctopus giganteus: A large cephalopod living in the tropical Atlantic.

Bruce Champagne

- 1A Long Necked: A 30-foot (9.1 m) sea lion with a long neck and long tail. The neck is the same thickness or smaller than the head. Hair reported. It is capable of travel on land. Cosmopolitan.

- 1B Long Necked: Similar to the above type but over 55 feet (17 m) long and far more robust. The neck is of lesser thickness than the head. Only inhabits water near Great Britain and Denmark.

- 2A Eel-Like: A 20–30-foot-long (6.1–9.1 m) heavily scaled or armored reptile. It is distinguished by a small square head with prominent tusks. "Motorboating" behavior on surface. Inhabits only the North Atlantic.

- 2B Eel-Like: A 25–30-foot (7.6–9.1 m) beaked whale. It is distinguished by a tapering head and a dorsal crest. "Motorboating" behavior engaged in. Inhabits the Atlantic and Pacific. Possibly extinct.

- 2C Eel-Like: A 60–70-foot (18–21 m), elongated reptile with no appendages. The head is very large and cow-like or reptilian with teeth similar to a crabeater seal's. Also shares the "motorboating" behavior. Inhabits the Atlantic, Pacific, and South China Sea. Possibly extinct.

- 3 Multi-Humped: 30–60 feet (9.1–18.3 m) long. A possible reptile with a dorsal crest and the ability to move in several undulations. The head has a distinctive "cameloid" appearance. Identical with Cadborosaurus willsi.

- 4A Sailfin: A 30–70-foot (9.1–21.3 m) beaked whale. It is distinguished by a very small head and a very large dorsal fin. Only found in the North West Atlantic. Possibly extinct.

- 4B Sailfin: An elongated animal of possible mammalian or reptilian identity reported to be 12–85 feet (3.7–25.9 m) long. It has a long neck with a turtle-like head and a long continuous dorsal fin. Cosmopolitan.

- 5 Carapaced: A large turtle or turtle-like creature (mammal?) reported to be 10–45 feet (3.0–13.7 m) long. Carapace is described as jointed, segmented, and plated. May exhibit a dorsal crest of "quills" and a type of oily hair. Cosmopolitan.

- 6 Saurian: A large and occasionally spotted crocodile or crocodile-like creature up to 65 feet (20 m) long. Found in the Northern Atlantic and Mediterranean.

- 7 Segmented/Multi limbed: An elongated mammalian creature up to 65 feet (20 m) long with the appearance of segmentation and many fins. Found in the Western Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific.

See also

References

- ↑ Bruce Champagne. "A Preliminary Evaluation of a Study of the Morphology, Behavior, Autoecology, and Habitat of Large, Unidentified Marine Animals, Based on Recorded Field Observations". In Craig Heinselman. Crypto. Dracontology (1): 99–118. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ↑ Sue Hamilton, Monsters, page 24 (ABDO Publishing Company, 2007). ISBN 978-1-59928-771-3

- ↑ "Sea Serpent?". By Ask.com. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ↑ "The Unexplained Mystery of the Sea Serpent". By Crypted Chronicles (March 18, 2012). Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ↑ http://loype.kulturminneaaret2009.no/kulturminneloyper/heilag-olav-i-valldal/ormen-i-syltefjellet/image/image_view_fullscreen

- ↑ http://www.nb.no/cgi-bin/galnor/gn_sok.sh?id=147257&skjema=2&fm=4

- ↑ "Norse Mythology - Jormungandr". By Oracle Thinkquest. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ↑ Water Monsters. Gail B. Stewart (author of the book) of Google Books. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ↑ Linnaean Society of New England (1817). Report of a Committee of the Linnaean Society of New England, relative to a large marine animal, supposed to be a serpent, seen near Cape Ann, Massachusetts, in August 1817. Boston: Cummings and Hilliard.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Poole, W. Scott. Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting. Waco, Texas: Baylor, 2011. ISBN 978-1-60258-314-6.

- ↑ Soini, Wayne. Gloucester's Sea Serpent. Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-59629-461-5.

- ↑ Eyers, Jonathan (2011). Don't Shoot the Albatross!: Nautical Myths and Superstitions. A&C Black, London, UK. ISBN 978-1-4081-3131-2.

- ↑ http://forteanzoology.blogspot.com/2010/06/dale-drinnon-extractions-from.html

- ↑ Drinnon, Dale A, "A preliminary Cryptozoological Checklist, p 85-126. CFZ Press, Myrtle Cottage, Devon, UK 2010

- ↑ http://forteanzoology.blogspot.com/search?q=Dale+Drinnon, DALE DRINNON: Possible Identifications for some of Bruce Champagne's Independent Sea-Serpent Classification Categories, blog of May 25, 2010

Further reading

- Coleman, Loren; Huyghe, Patrick (2003). The Field Guide to Lake Monsters, Sea Serpents, and Other Mystery Denizens of the Deep. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher. ISBN 1-58542-252-5.

- Heuvelmans, Bernard (1968). In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents. Hill and Wang.

- Oudemans, A. C. (1892). The Great Sea Serpent. Luzac & Co.

- Mareš, J. (1997). Svět tajemných zvířat. Prague. ISBN 80-85916-16-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sea serpent. |

- Video of the oarfish, a creature that inspired the sea serpent mythology.

- The Cryptid Zoo: Sea Serpents

- A sea serpent in Iceland