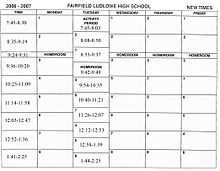

School timetable

A school timetable is a table for coordinating these four elements:

- Students

- Teachers

- Rooms

- Time slots (also called periods)

Other factors include the subject of the class, and the type of classrooms available (for example, science laboratories).

School timetables usually cycle every week or every fortnight. The phrase "school timetables" largely refers to high schools, because primary schools typically have simple structures.

High school timetables are quite different from university timetables. The main difference is the fact that in high schools, students have to be occupied and supervised every hour of the school day, or nearly every hour. Also, high school teachers generally have much higher teaching loads than is the case in universities. As a result, it is generally considered that university timetables involve more human judgement whereas high school timetabling is a more computationally intensive task, see constraint satisfaction problem.

- Block: This term is ambiguous, but in this article it refers to a set of lessons of different courses that must be placed concurrently.

- Student body: A set of students who are timetabled together, for example the 8A roll-call group.

- Band (or Cluster): A set of classes involving the same student body, which are therefore horizontally linked, meaning they must be on separate periods

- Year group or Year level: A set of students at the same stage of their schooling, for example Year 9.

- Elective line: A block of many classes of many subjects such that each student may choose one subject from the line.

Types of school timetables

Primary schools typically have timetables, however the timetable is usually so simple that it can be constructed manually or in a basic spreadsheet package.

In some countries and regions, such as China and East Africa, high school students are not given any choice in subjects, and this makes timetabling easy - the students can remain in the one room all day while the teachers rotate.

In other countries, such as USA, the whole school is typically run on a system of units, where each subject has the same number of lessons per cycle and subjects are placed into 'lines'. This also makes timetabling easy.

In other countries, such as Australia, Canada, and most European countries, timetables can be extremely difficult to construct. The process can take weeks of effort and typically computers are needed in the process.

In Indian context school time table is of four types- a)General Time table -it includes general information of the proceedings; b)Time table for teachers where they can see their allotted classes throughout the week; c)A time table for students to manage themselves accordingly & d)Provisional time table - It keeps record of the absentee teachers and make shift arrangements for that.

Problems and issues involved

The task of constructing a high school timetable involves the following issues (not an exhaustive list): ed and these must be shared fairly across all classes

- Some schools assign the same number of periods to all subjects, but more commonly (at least outside USA) there are a variety of lengths of classes: 9 periods per cycle, 8, 7, 5 and so on. If this is the case, it means that it's not possible to have a 'coherent' structure to the timetable. 'Coherent' means that the classes in each year match up neatly with classes in other years in school-wide 'super-columns'. Non coherent timetables are much more difficult to construct.

- Occasionally there is 'vertical integration': a class from one year has a requirement to line up with a particular class from the next year. This happens mainly when students are allowed to take subjects in a higher not teach on those periods.

- Part-time teachers need to have certain entire days off. They will either specify to the school which weekdays they are or simply how many days per cycle they need off. Such teachers can greatly add to the difficulty of timetabling when they are assigned to large blocks.

- Sometimes two schools try to coordinate their timetables in order to be able to share a small number of staff. Often the schools have different bell times. Often also there is travel time between campuses which must be taken into consideration.

- Sometimes a school is spread over 2 or more campuses, and the timetable should minimise the amount of cross-campus travel for students and teachers. Furthermore, where travel occurs, the travel time must be taken into consideration.

- Sometimes there are constraints imposed from external organizations, such as sports venues bookings or technical education for senior students.

- Sometimes there are 2 or 3 subjects which rotate between student bodies throughout the year. For example, the 8A students might take Art in the first half of the year and Music in the second half.

- Classes should be assigned rooms in a way which attempts to give the same room to the same class (for primary schools) or the same room to the same teacher (for most high schools/secondary schools) for all or most lessons ('room constancy').

- Sometimes it is unavoidable to have what is known as a 'split class': this is a class where one teacher takes it for some lessons and another teacher for other lessons. This can happen e.g. because no single teacher is available on all scheduled periods, or because no single teacher can take it without going over their maximum teaching load.

Another definition for a split class is when a teacher must teach two different grade levels in one period (for example Grade 10 French and Grade 11 French). This often occurs with less popular subjects, which are not big enough to be made into separate classes. Split classes are generally deemed highly undesirable. - Off-timetable lessons: sometimes an occasional lesson is scheduled "off the timetable" meaning before school or after school or during lunch. This usually happens with older students. It can be a desperate response to intractable timetabling problems or a compromise reached in order for the school to be able to offer less popular subjects.

Elective lines

A central issue which exists both in the American model (all lessons in all year-levels are organised into lines) and the European model (containing all the complexities listed above) is to provide an individualised curriculum for each student that provides for his/her strengths, weaknesses and personal preferences. Certain subjects lend themselves to setting, or organising students into ability groups. Mathematics is a good example, where some students in the same age range may be literally years ahead of their peers. There are other subjects where students benefit from placement in mixed ability groups. This is an ongoing debate among teachers.

It is widely believed that students should have a broad curriculum in their early years at school but that it should become increasingly specialised and deeper as they get older.

Thus, many secondary schools introduce “options” or “electives”, typically at the age of 14. This presents the timetabler with many restrictions, since in any one teaching period several different subject specialists will be teaching that group of students. This is in contrast to the example above – Mathematics – where the same group will all be taught by Mathematics specialists.

There are many schools that fix their option blocks such that students must choose one subject in each block. This is a very poor way of approaching the problem, although in small schools staffing restrictions make it essential.

In larger schools, there is usually sufficient flexibility in staffing to allow students a free choice and staffing can then be adjusted accordingly. Large schools have the additional advantage that they can offer a wider range of subjects including those that only small numbers of students select.

The downside is that the bigger a school becomes, the less intimate it becomes. In a school of 300 students, it is reasonable to suppose that every individual student and teacher can “know” each other. In a school of 1,500 or more, this is practically impossible. A fair compromise is in the range of 700-1200.

For the timetabler, once the number of lessons for each subject are agreed, (The Curriculum) the sets and option blocks are the first thing to establish and fix. These can be thought of as stones in a river, and once fixed, the rest of the timetable flows around these mainly unmoveable lumps. This is especially true with courses that last more than one year, where it is preferable to have continuity with the same group and the same teacher.

Constructing a secondary school timetable is complex but is more a problem of persistence than intelligence. In the long process it requires thousands of decisions, some of which are obscure in the extreme. Retaining flexibility as that process develops is the key issue.

Constructing a large secondary school’s timetable is not simply a case of filling in a matrix, difficult though that often is. The timetable determines the movements of many hundreds of people for a year of their lives. All timetables are compromises between a myriad of differing interests and preferences. It requires an intimate knowledge of the detail of the lives of that community. It is not firstly a mathematical or organisational problem, it is a human one.

See also

- Block scheduling: When students have fewer, longer classes each day.

External links

- PATAT Conferences The International Series of Conferences on the Practice and Theory of Automated Timetabling

- International Timetabling Competition 2007

- Robertus J. Willemen, School timetable construction, Algorithms and complexity