Schedule (computer science)

In the fields of databases and transaction processing (transaction management), a schedule (or history) of a system is an abstract model to describe execution of transactions running in the system. Often it is a list of operations (actions) ordered by time, performed by a set of transactions that are executed together in the system. If order in time between certain operations is not determined by the system, then a partial order is used. Examples of such operations are requesting a read operation, reading, writing, aborting, committing, requesting lock, locking, etc. Not all transaction operation types should be included in a schedule, and typically only selected operation types (e.g., data access operations) are included, as needed to reason about and describe certain phenomena. Schedules and schedule properties are fundamental concepts in database concurrency control theory.

Formal description

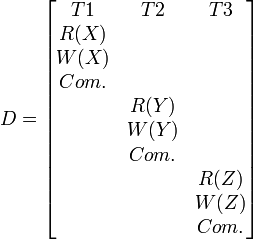

The following is an example of a schedule:

In this example, the horizontal axis represents the different transactions in the schedule D. The vertical axis represents time order of operations. Schedule D consists of three transactions T1, T2, T3. The schedule describes the actions of the transactions as seen by the DBMS. First T1 Reads and Writes to object X, and then Commits. Then T2 Reads and Writes to object Y and Commits, and finally T3 Reads and Writes to object Z and Commits. This is an example of a serial schedule, i.e., sequential with no overlap in time, because the actions of in all three transactions are sequential, and the transactions are not interleaved in time.

Representing the schedule D above by a table (rather than a list) is just for the convenience of identifying each transaction's operations in a glance. This notation is used throughout the article below. A more common way in the technical literature for representing such schedule is by a list:

- D = R1(X) W1(X) Com1 R2(Y) W2(Y) Com2 R3(Z) W3(Z) Com3

Usually, for the purpose of reasoning about concurrency control in databases, an operation is modeled as atomic, occurring at a point in time, without duration. When this is not satisfactory start and end time-points and possibly other point events are specified (rarely). Real executed operations always have some duration and specified respective times of occurrence of events within them (e.g., "exact" times of beginning and completion), but for concurrency control reasoning usually only the precedence in time of the whole operations (without looking into the quite complex details of each operation) matters, i.e., which operation is before, or after another operation. Furthermore, in many cases the before/after relationships between two specific operations do not matter and should not be specified, while being specified for other pairs of operations.

In general operations of transactions in a schedule can interleave (i.e., transactions can be executed concurrently), while time orders between operations in each transaction remain unchanged as implied by the transaction's program. Since not always time orders between all operations of all transactions matter and need to be specified, a schedule is, in general, a partial order between operations rather than a total order (where order for each pair is determined, as in a list of operations). Also in the general case each transaction may consist of several processes, and itself be properly represented by a partial order of operations, rather than a total order. Thus in general a schedule is a partial order of operations, containing (embedding) the partial orders of all its transactions.

Time-order between two operations can be represented by an ordered pair of these operations (e.g., the existence of a pair (OP1,OP2) means that OP1 is always before OP2), and a schedule in the general case is a set of such ordered pairs. Such a set, a schedule, is a partial order which can be represented by an acyclic directed graph (or directed acyclic graph, DAG) with operations as nodes and time-order as a directed edge (no cycles are allowed since a cycle means that a first (any) operation on a cycle can be both before and after (any) another second operation on the cycle, which contradicts our perception of Time). In many cases a graphical representation of such graph is used to demonstrate a schedule.

Comment: Since a list of operations (and the table notation used in this article) always represents a total order between operations, schedules that are not a total order cannot be represented by a list (but always can be represented by a DAG).

Types of schedule

Serial

The transactions are executed non-interleaved (see example above) i.e., a serial schedule is one in which no transaction starts until a running transaction has ended.

Serializable

A schedule that is equivalent (in its outcome) to a serial schedule has the serializability property.

In schedule E, the order in which the actions of the transactions are executed is not the same as in D, but in the end, E gives the same result as D.

Conflicting actions

Two actions are said to be in conflict (conflicting pair) if:

- The actions belong to different transactions.

- At least one of the actions is a write operation.

- The actions access the same object (read or write).

The following set of actions is conflicting:

- R1(X), W2(X), W3(X) (3 conflicting pairs)

While the following sets of actions are not:

- R1(X), R2(X), R3(X)

- R1(X), W2(Y), R3(X)

Conflict equivalence

The schedules S1 and S2 are said to be conflict-equivalent if following two conditions are satisfied:

- Both schedules S1 and S2 involve the same set of transactions (including ordering of actions within each transaction).

- The set of conflicting pairs in S1 is the same as in S2.

Conflict-serializable

A schedule is said to be conflict-serializable when the schedule is conflict-equivalent to one or more serial schedules.

Another definition for conflict-serializability is that a schedule is conflict-serializable if and only if its precedence graph/serializability graph, when only committed transactions are considered, is acyclic (if the graph is defined to include also uncommitted transactions, then cycles involving uncommitted transactions may occur without conflict serializability violation).

Which is conflict-equivalent to the serial schedule <T1,T2>, but not <T2,T1>.

Commitment-ordered

A schedule is said to be commitment-ordered (commit-ordered), or commitment-order-serializable, if it obeys the Commitment ordering (CO; also commit-ordering or commit-order-serializability) schedule property. This means that the order in time of transactions' commitment events is compatible with the precedence (partial) order of the respective transactions, as induced by their schedule's acyclic precedence graph (serializability graph, conflict graph). This implies that it is also conflict-serializable. The CO property is especially effective for achieving Global serializability in distributed systems.

Comment: Commitment ordering, which was discovered in 1990, is obviously not mentioned in (Bernstein et al. 1987). Its correct definition appears in (Weikum and Vossen 2001), however the description there of its related techniques and theory is partial, inaccurate, and misleading. For an extensive coverage of commitment ordering and its sources see Commitment ordering and The History of Commitment Ordering.

View equivalence

Two schedules S1 and S2 are said to be view-equivalent when the following conditions are satisfied:

- If the transaction

in S1 reads an initial value for object X, so does the transaction

in S1 reads an initial value for object X, so does the transaction  in S2.

in S2. - If the transaction

in S1 reads the value written by transaction

in S1 reads the value written by transaction  in S1 for object X, so does the transaction

in S1 for object X, so does the transaction  in S2.

in S2. - If the transaction

in S1 is the final transaction to write the value for an object X, so is the transaction

in S1 is the final transaction to write the value for an object X, so is the transaction  in S2.

in S2.

View-serializable

A schedule is said to be view-serializable if it is view-equivalent to some serial schedule. Note that by definition, all conflict-serializable schedules are view-serializable.

Notice that the above example (which is the same as the example in the discussion of conflict-serializable) is both view-serializable and conflict-serializable at the same time.) There are however view-serializable schedules that are not conflict-serializable: those schedules with a transaction performing a blind write:

The above example is not conflict-serializable, but it is view-serializable since it has a view-equivalent serial schedule <T1, T2, T3>.

Since determining whether a schedule is view-serializable is NP-complete, view-serializability has little practical interest.

Recoverable

Transactions commit only after all transactions whose changes they read, commit.

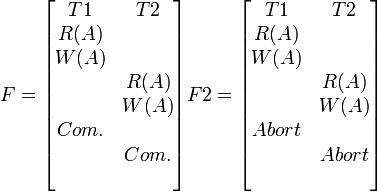

These schedules are recoverable. F is recoverable because T1 commits before T2, that makes the value read by T2 correct. Then T2 can commit itself. In F2, if T1 aborted, T2 has to abort because the value of A it read is incorrect. In both cases, the database is left in a consistent state.

Unrecoverable

If a transaction T1 aborts, and a transaction T2 commits, but T2 relied on T1, we have an unrecoverable schedule.

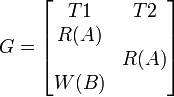

In this example, G is unrecoverable, because T2 read the value of A written by T1, and committed. T1 later aborted, therefore the value read by T2 is wrong, but since T2 committed, this schedule is unrecoverable.

Avoids cascading aborts (rollbacks)

Also named cascadeless. A single transaction abort leads to a series of transaction rollback. Strategy to prevent cascading aborts is to disallow a transaction from reading uncommitted changes from another transaction in the same schedule.

The following examples are the same as the one from the discussion on recoverable:

In this example, although F2 is recoverable, it does not avoid cascading aborts. It can be seen that if T1 aborts, T2 will have to be aborted too in order to maintain the correctness of the schedule as T2 has already read the uncommitted value written by T1.

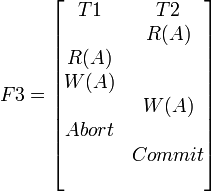

The following is a recoverable schedule which avoids cascading abort. Note, however, that the update of A by T1 is always lost (since T1 is aborted).

Cascading aborts avoidance is sufficient but not necessary for a schedule to be recoverable.

Strict

A schedule is strict - has the strictness property - if for any two transactions T1, T2, if a write operation of T1 precedes a conflicting operation of T2 (either read or write), then the commit event of T1 also precedes that conflicting operation of T2.

Any strict schedule is cascadeless, but not the converse. Strictness allows efficient recovery of databases from failure.

Hierarchical relationship between serializability classes

The following expressions illustrate the hierarachical (containment) relationships between serializability and recoverability classes:

- Serial ⊂ commitment-ordered ⊂ conflict-serializable ⊂ view-serializable ⊂ all schedules

- Serial ⊂ strict ⊂ avoids cascading aborts ⊂ recoverable ⊂ all schedules

The Venn diagram (below) illustrates the above clauses graphically.

Practical implementations

In practice, most general purpose database systems employ conflict-serializable and recoverable (primarily strict) schedules.

See also

References

- Philip A. Bernstein, Vassos Hadzilacos, Nathan Goodman: Concurrency Control and Recovery in Database Systems, Addison Wesley Publishing Company, 1987, ISBN 0-201-10715-5

- Gerhard Weikum, Gottfried Vossen: Transactional Information Systems, Elsevier, 2001, ISBN 1-55860-508-8