Scansoriopterygidae

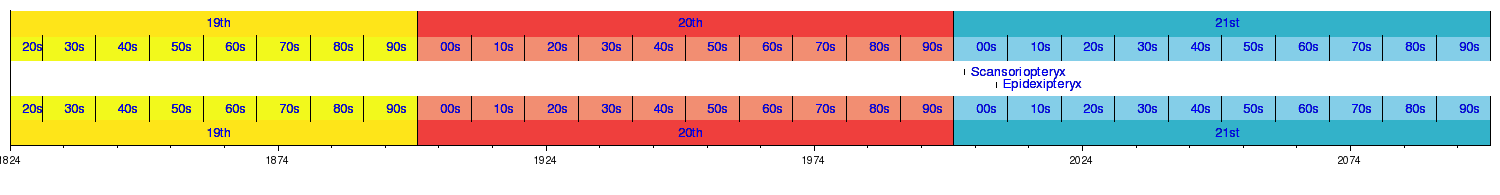

| Scansoriopterygids Temporal range: Late Jurassic, 160Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist's restoration of Epidexipteryx hui | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Paraves |

| Family: | †Scansoriopterygidae Czerkas & Yuan, 2002 |

| Type species | |

| Scansoriopteryx heilmanni Czerkas & Yuan, 2002 | |

| Genera | |

Scansoriopterygidae (meaning "climbing wings") is a family of maniraptoran dinosaurs, known from three well-preserved fossils unearthed in the Daohugou fossil beds (possibly dating to the mid-late Jurassic Period) of Liaoning, China.

Scansoriopteryx (and its likely synonym Epidendrosaurus) was the first non-avian dinosaur found that had clear adaptations to an arboreal or semi-arboreal lifestyle–it is likely that they spent much of their time in trees. Both specimens showed features indicating they were juveniles, which made it difficult to determine their exact relationship to other non-avian dinosaurs and birds. It was not until the description of Epidexipteryx in 2008 that an adult specimen was known. The type specimen of Scansoriopteryx (type genus of the Scansoriopterygidae) and its arboreal adaptations were first presented in 2000 during the Florida Symposium on Dinosaur/Bird Evolution, at the Graves Museum of Archaeology & Natural History, though the specimen would not be formally described and named until 2002.[1]

Description

Scansoriopterygids are among the smallest dinosaurs known. The juvenile specimens of Scansoriopteryx are the size of House Sparrows,[2] about 16 centimeters long, while the adult type specimen of Epidexipteryx is about the size of a Pigeon, about 25 centimeters long (not including the tail feathers).[3]

Scansoriopterygids can be characterized by their extremely elongated third fingers, which are longer than the first and second digits of the hand (in all other known theropods, the second finger is the longest). Other features shared within the group include short and high skulls with down turned lower jaws and large front teeth, and long arms. Tail length, however, varied significantly among scansoriopterygids. Epidexipteryx had a short tail (70% the length of the torso), anchoring long tail feathers, while Scansoriopteryx had a very long tail (over three times as long as the torso) with a short spray of feathers at the tip. All three described scansoripterygid specimens preserve the fossilized traces of feathers covering their bodies.[1][2][4]

Classification

Scansoriopterygidae was created as a family-level taxon by Stephen Czerkas and Yuan Chongxi in 2002. Some scientists, such as Paul Sereno, initially considered the concept redundant because the group was originally monotypic, containing only the single genus and species Scansoriopteryx heilmanni. Additionally, the group lacked a phylogenetic definition.[5] However, in 2008 Zhang et al. reported another scansoriopterygid, Epidexipteryx, and defined Scansoriopterygidae as a clade comprising most recent common ancestor of Epidexipteryx and Epidendrosaurus (=Scansoriopteryx") plus all its descendants.[4]

The exact taxonomic placement of this group was initially uncertain and controversial. When describing the first validly published specimen in 2002 (Scansoriopteryx heilmanni), Czerkas and Yuan proposed that various primitive features of the skeleton (including a primitive, "saurischian-style" pubis and primitive hip joint) showed that scansoriopteryds, along with other maniraptorans and birds, split from other theropods very early in dinosaur evolution.[1] However, this interpretation has not been followed by most other researchers. In a 2007 cladistic analysis of relationships among coelurosaurs, Phil Senter found Scansoriopteryx to be the closest dinosaurian relative of avian birds, and a member of the clade Avialae.[6] This view was supported by a second phylogenetic analysis performed by Zhang et al. in 2008. These authors included the additional taxon Epidexipteryx, and found that it formed a clade with Scansoriopteryx at the base of Avialae.[4] An abbreviated version of Zhang et al.'s 2008 cladogram is presented below.

| Maniraptora |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

A subsequent phylogenetic analysis conducted by Agnolín and Novas (2011) recovered scansoriopterygids not as avialans, but as basal members of the clade Paraves remaining in unresolved polytomy with alvarezsaurids and the clade Eumaniraptora (containing avialans and deinonychosaurs).[7]

Turner, Makovicky and Norell (2012) included only Epidexipteryx hui in their primary phylogenetic analysis, as a full-grown specimen of this species is known; regarding Scansoriopteryx/Epidendrosaurus, the authors were worried that including it in the primary analysis would be problematic, because it is only known from juvenile specimens, which "do not necessarily preserve all the adult morphology needed to accurately place a taxon phylogenetically" (Turner, Makovicky and Norell 2012, p. 89). Epidexipteryx was recovered as basal paravian that didn't belong to Eumaniraptora. The authors did note that its phylogenetic position is unstable; constraining Epidexipteryx hui as a basal avialan required two additional steps compared to the most parsimonious solution, while constraining it as a basal member of Oviraptorosauria required only one additional step. A separate exploratory analysis included Scansoriopteryx/Epidendrosaurus, which was recovered as a basal member of Avialae; the authors noted that it did not clade with Epidexipteryx, which stayed outside Eumaniraptora. Constraining the monophyly of Scansoriopterygidae required four additional steps and moved Epidexipteryx into Avialae.[8]

A monophyletic Scansoriopterygidae was recovered by Godefroit et al. (2013); the authors found scansoriopterygids to be basalmost members of Paraves and the sister group to the clade containing Avialae and Deinonychosauria.[9] Agnolín and Novas (2013) recovered scansoriopterygids as non-paravian maniraptorans and the sister group to Oviraptorosauria.[10]

Provenance and paleoecology

The fossil remains of Epidexipteryx and Scansoriopteryx were recovered from the Daohugou Beds of northeastern China. The age of these fossil beds is not resolved, and studies have variously proposed dates ranging between some 170 to about 120 mya (Middle Jurassic to Early Cretaceous).[11][12]

The known scansoriopterygids of the Daohugou biota inhabited a humid, temperate forest made up of a variety of prehistoric trees including species of ginkgo and conifer. The understory would have been dominated by plants such as club mosses, horsetails, cycads, and ferns.[13]

The scansoriopterygids would have lived alongside synapsids such as the aquatic Castorocauda and arboreal gliding mammal Volaticotherium, the rhamphorhynchoid pterosaurs Jeholopterus and Pterorhynchus, as well as a diverse range of insect life (including mayflies and beetles) and several species of salamander.[14][15]

Paleobiology

Climbing

In the initial descriptions of the first two scansoriopterygid specimens, scientists studying these animals used several lines of evidence to argue that they were arboreal (tree-climbing), and the first known non-avian dinosaurs with clear climbing adaptations.

Zhang and colleagues considered Scansoriopteryx to be arboreal based on the elongated nature of the hand and specializations of the foot. These authors stated that the long hand and strongly curved claws were adaptations for climbing and moving around among tree branches. They viewed this as an early stage in the evolution of the bird wing, stating that the forelimbs became well-developed for climbing, and that this development later lead to the evolution of a wing capable of flight. They argued that long, grasping hands are more suited to climbing than to flight, since most flying birds have relatively short hands. Zhang et al. also noted that the foot of Scansoriopteryx is unique among non-avian theropods; while Scansoriopteryx does not preserve a reversed hallux (the backward-facing toe seen in modern perching birds), its foot was very similar in construction to primitive perching birds like Cathayornis and Longipteryx. These adaptations for grasping ability in all four limbs, the authors argued, makes it likely that Scansoriopteryx spent a significant amount of time living in trees.[2]

In describing Scansoriopteryx, Czerkas and Yuan also described evidence for an arboreal lifestyle. They noted that, unlike all modern bird hatchlings, the forelimbs of Scansoriopteryx are longer than the hind limbs. The authors argued that this anomaly indicates the forelimbs played an important role in locomotion even at an extremely early developmental stage. Scansoriopteryx has a better-preserved foot than the type of Epidendrosaurus, and the authors interpreted the hallux as reversed, the condition of a backward-pointing toe being widespread among modern tree-dwelling birds. Furthermore, the authors pointed to the stiffened tail of Scansoriopteryx as a tree-climbing adaptation. The tail may have been used as a prop, much like the tails of modern woodpeckers. Comparison with the hands of modern climbing species with elongated third digits, like iguanid lizards, also supports the tree-climbing hypothesis. Indeed, the hands of Scansoriopteryx are much better adapted to climbing than the modern tree-climbing hatchling of the Hoatzin.[1]

Feathers

Both juvenile scansoriopterygid specimens preserve impressions of simple, down-like feathers, especially around the hand and arm. The longer feathers in this region led Czerkas and Yuan to speculate that adult scansoriopterygids may have had reasonably well-developed wing feathers which could have aided in leaping or rudimentary gliding, though they ruled out the possibility that Scansoriopteryx could have achieved powered flight. Like other maniraptorans, scansoriopterygids had a semilunate carpal (half-moon shaped wrist bone) that allowed for bird-like folding motion in the hand. Even if powered flight was not possible, this motion could have aided maneuverability in leaping from branch to branch.[1]

The adult specimen of Epidexipteryx lacked preserved feathers around the forelimbs, but preserved simple feathers on the body and long, ribbon-like feathers on the tail. The tail feathers, likely used in display, consisted of a central shaft (rachis) and unbranched vane (unlike the vanes of modern feathers, which are broken up into smaller filaments or barbs).[4]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Czerkas, S.A., and Yuan, C. (2002). "An arboreal maniraptoran from northeast China." Pp. 63-95 in Czerkas, S.J. (Ed.), Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight. The Dinosaur Museum Journal 1. The Dinosaur Museum, Blanding, U.S.A. PDF abridged version

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Zhang F., Zhou Z., Xu X., Wang X. (2002). "A juvenile coelurosaurian theropod from China indicates arboreal habits". Naturwissenschaften 89: 394–398. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0353-8. PMID 12435090.

- ↑ Zhang, F., Zhou, Z., Xu, X., Wang, X. and Sullivan, C. (2008). "A bizarre Jurassic maniraptoran from China with elongate ribbon-like feathers", Supplementary Information. Nature, 455: 46pp. doi:10.1038/nature07447 PMID 18948955

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Zhang, F., Zhou, Z., Xu, X., Wang, X., & Sullivan, C. (2008). "A bizarre Jurassic maniraptoran from China with elongate ribbon-like feathers." Available from Nature Precedings, doi:10.1038/npre.2008.2326.1 PDF full text.

- ↑ Sereno, P. C. (2005). "Scansoriopterygidae." Stem Archosauria—TaxonSearch [version 1.0, 2005 November 7]

- ↑ Senter, P. (2007). "A new look at the phylogeny of Coelurosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda)." Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, (doi:10.1017/S1477201907002143).

- ↑ Agnolín, Federico L.; Novas, Fernando E. (2011). "Unenlagiid theropods: are they members of the Dromaeosauridae (Theropoda, Maniraptora)?". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 83 (1): 117–162. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652011000100008.

- ↑ Alan Hamilton Turner, Peter J. Makovicky and Mark Norell (2012). "A review of dromaeosaurid systematics and paravian phylogeny". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 371: 1–206. doi:10.1206/748.1.

- ↑ Pascal Godefroit, Helena Demuynck, Gareth Dyke, Dongyu Hu, François Escuillié and Philippe Claeys (2013). "Reduced plumage and flight ability of a new Jurassic paravian theropod from China". Nature Communications 4: Article number 1394. doi:10.1038/ncomms2389. PMID 23340434.

- ↑ Federico L. Agnolín and Fernando E. Novas (2013). "Avian ancestors. A review of the phylogenetic relationships of the theropods Unenlagiidae, Microraptoria, Anchiornis and Scansoriopterygidae". SpringerBriefs in Earth System Sciences: 1–96. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5637-3.

- ↑ Liu Y., Liu Y., Zhang H. (2006). "LA-ICPMS zircon U-Pb dating in the Jurassic Daohugou Beds and correlative strata in Ningcheng of Inner Mongolia". Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition) 80 (5): 733–742.

- ↑ Wang X., Zhou Z., He H., Jin F., Wang Y., Wang Y., Zhang J., Xu X., Zhang F. et al. (2005). "Stratigraphy and age of the Daohugou Bed in Ningcheng, Inner Mongolia". Chinese Science Bulletin 50 (20): 2369–2376. doi:10.1007/BF03183749.

- ↑ Zhang K., Yang D., Dong R. (2006). "The first snipe fly (Diptera: Rhagionidae) from the Middle Jurassic of Inner Mongolia, China". Zootaxa 1134: 51–57.

- ↑ Meng J., Hu Y., Li C., Wang Y. (2006). "The mammal fauna in the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota: implications for diversity and biology of Mesozoic mammals". Geological Journal 41: 439–463. doi:10.1002/gj.1054.

- ↑ Wang X., Zhou Z. (2006). "Pterosaur assemblages of the Jehol Biota and their implication for the Early Cretaceous pterosaur radiation .". Geological Journal 41: 405–418. doi:10.1002/gj.1046.