Scanner (radio)

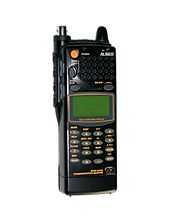

A scanner is a radio receiver that can automatically tune, or scan, two or more discrete frequencies, stopping when it finds a signal on one of them and then continuing to scan other frequencies when the initial transmission ceases.

The terms radio scanner or police scanner generally refer to a communications receiver that is primarily intended for monitoring VHF and UHF landmobile radio systems, as opposed to, say, a receiver used to monitor international shortwave transmissions.

More often than not, these scanners can also tune to different types of modulation as well (AM, FM, WFM, etc.). Early scanners were slow, bulky, and expensive. Today, modern microprocessors have enabled scanners to store thousands of channels and monitor hundreds of channels per second. Recent models can follow trunked radio systems and decode APCO-P25 digital transmissions. Both hand held and desktop models are available. Scanners are often used to monitor police, fire and emergency medical services. Radio scanning serves an important role in the fields of journalism and crime investigation, as well as a hobby for many people around the world.

History and use

Scanners developed from earlier tunable and fixed-frequency radios that received one frequency at a time. Non-broadcast radio systems, such as those used by public safety agencies, do not transmit continuously. With a radio fixed on a single frequency, much time could pass between transmissions, while other frequencies might be active. A scanning radio will sequentially monitor multiple programmed channels, or search between user defined frequency limits. The scanner will stop on an active frequency strong enough to break the radio's squelch setting and resume scanning other frequencies when that activity ceases.

Scanners first became popular and widely available during the heyday of CB radio in the 1970s. The first scanners often had between four and ten channels and required the purchase of a separate crystal for each frequency received. A US patent was issued to Peter W. Pflasterer on June 1, 1976.[1] An early 1976 US entry was the Tennelec MCP-1, sold at the January, 1976 Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago.[2][3]

Features

Many recent models will allow scanning of the specific DCS or CTCSS code used on a specific frequency should it have multiple users. One memory bank can be assigned to air traffic control, another can be for local marine communications, and yet another for local police frequencies. These can be switched on and off depending on the user's preference. Most scanners have a weather radio band, allowing the listener to tune into weather radio broadcasts from a NOAA transmitter.

Some scanners are equipped with Fire-Tone out. Fire tone out decodes Quick Call type tones and acts as a pager when the correct sequence of tones is detected.

Modern scanners allow hundreds or thousands of frequencies to be entered via a keypad and stored in various 'memory banks' and can scan at a rapid rate due to modern microprocessors.

Active frequencies can be found by searching the internet and frequency reference books[4] or can be discovered through a programmable scanner's search function. An external antenna for a desktop scanner or an extendable antenna for a hand held unit will provide greater performance than the original equipment antennas provided by manufacturers.

As radio systems have become more complex, including several different types of trunked radio systems such as Motorola, EDACS, LTR as well as digital, scanners have also become increasingly more complex. This has had the result of reducing access to monitoring public safety communications systems for all but the most hard-core users. The need to know detailed information about how radio systems work is a significant hurdle for the market. Recently, however, database-driven scanners have been introduced that greatly reduce the need for end-users to know the details of the radio systems that they want to monitor. One such model, the Uniden HomePatrol-1, includes the entire database of USA and Canada radio systems from RadioReference.com. All the user needs to do is input their location (typically just their zip code) and the scanner automatically selects the appropriate radio channels for their area. When attached to a GPS receiver, even this requirement is removed, as the scanner will automatically determine its position and continuously update the systems as the user relocates.

Uses

Scanners are used by hobbyists, railfans, off duty emergency services personnel, reporters, and criminals.

Many scanner clubs exist to allow members to share information about frequencies, codes and operations. Most have Internet presence, such as websites, email lists or Web forums. The Chicago Area Radio Monitoring Association (CARMA) is an example.

Legislation

Australia

It is legal to possess a scanner in Australia. It is legal to listen to any transmission that is not classified as telecommunication (i.e. anything not connected to the telephone network).

New Zealand

In New Zealand, according to the Radiocommunications Act 1989[5] it is legal to possess and use a scanner at any time to tune to any private voice radio (not encrypted data) provided that private information is not passed on or disclosed to any other person(s) or party(s).

North America

The legality of radio scanners varies considerably between jurisdictions. In the United States it is a federal crime to monitor cellular phone calls. Some US states prohibit the use of a scanner in an automobile. Although scanners capable of following trunked radio systems and demodulating some digital radio systems such as APCO Project 25 are available, decryption-capable scanners would be a violation of United States law and possibly laws of other countries.[citation needed]

A law passed by the Congress of the United States, under the pressure from cellular telephone interests, prohibited scanners sold after a certain date from receiving frequencies allocated to the Cellular Radio Service. The law was later amended to make it illegal to modify radios to receive those frequencies, and also to sell radios that could be easily modified to do so.[6] This law remains in effect even though few cellular subscribers still use analogue technology. There are Canadian and European unblocked versions available, but these are illegal to import into the U.S. Frequencies used by early cordless phones at 43.720–44.480 MHz, 46.610–46.930 MHz, and 902.000–906.000 MHz can be picked up by many scanners. The proliferation of scanners led most cordless phone manufacturers to produce cordless handsets operating on a more secure 2.4 GHz system using spread-spectrum technology. Certain states in the U.S., such as New York and Florida, prohibit the use of scanners in a vehicle unless the operator has a radio license issued from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) (Amateur Radio, etc.)[7][8] or the operator's job requires the use of a scanner in a vehicle (e.g., police, fire, utilities).[citation needed]

In some parts of the United States, there are extra penalties for the possession of a scanner during a crime, and some states, such as Michigan, also prohibit the possession of a scanner by a person who has been convicted of a felony in the last 5 years.[9]

In the United States, the general guidelines to follow when using a radio scanner are that it is illegal to:[citation needed]

- Listen in on cellular and cordless phone calls

- Intercept encrypted or scrambled communications

- Sell or import radio scanners that are capable of receiving cellular phone frequencies (this rule does not apply to sales by individuals[citation needed] and radio scanners made before the ban)

- Modify radio scanners so that cellular phone frequencies can be received

- Use information received for personal gain (a common example is where a taxi driver listens to a competitor's dispatch channel to steal a customer)

- Use information received to aid in the commission or execution of a crime

- Disclose information received to other persons

Licensed Amateur Radio Operators with a valid FCC License may possess Amateur Radio Transceivers capable of reception beyond the Amateur Radio Bands per an FCC Memorandum & Order known as FCC Docket PR91-36 (also known as FCC 93-410).[10][11]

In Canada, according to the Radiocommunication Act,[12] it is completely legal to install, operate or possess a radio apparatus that is capable only of the reception of broadcasting (digital and analogue, but not encrypted data) provided that private information is not passed on or disclosed to any other person(s) or party(s).

A situation that occurred in the Toronto area on 28 June 2011 involving York Regional Police officer Constable Garret Styles was picked up by scanners. On-line streaming of communications between the officer and police dispatch while the fatally injured officer was in urgent need of emergency help were picked up by local media. The tragedy was widely reported before the officers family was notified. Several media outlets rebroadcast the recorded emergency transmission. A police initiative pressuring the government to create legislation to stop online streaming of scanner captured police communications was announced In April 2012.[13] Although it is currently legal to stream information from a scanner in Canada[citation needed], using the information for profit is not legal. Some Canadian police forces use encrypted communications which cannot legally be unencrypted and streamed onto the Internet. Applications are available permitting anyone with an Internet ready computer or smart phone to access scanner communications that are streamed onto the Internet by private individuals who possess the appropriate scanner and computer equipment.

In Mexico it is legal to have an unblocked scanner and listen to any radio spectrum frequencies including encrypted and cellular band. According to the Federal Law of General Ways of Communication, individuals are prohibited from spreading any information obtained via the mass media.[14]

South America

In Brazil it is legal to have a scanner, but the user should have a ham radio license. Individuals are prohibited from spreading or recording any information obtained.

See also

- Two-way radio

- Trunked radio system

- Communications receiver

- Chicago Area Radio Monitoring Association

- GRE (company)

- Uniden

References

- ↑ http://www.google.com/patents/about?id=sAIuAAAAEBAJ

- ↑ "Tennelec". allexperts.com/. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ↑ Curtis, Anthony R. (July 1977). "Computerized scanners". Popular Mechanics 148 (1): 68–70. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ↑ Kneitel, Tom (1986). The "Top Secret" registry of U.S. Government radio frequencies. Commack, NY: CRB Research. ISBN 0-939780-06-2.

- ↑ Radiocommunications Act 1989

- ↑ FCC (1997-07-10). DA 97-1440: Manufacturing Illegal Scanners Includes Scanner Modification. Federal Communications Commission, 10 July 1997. Retrieved from http://www.fcc.gov/Bureaus/Engineering_Technology/Public_Notices/1997/da971440.txt.

- ↑ http://public.leginfo.state.ny.us/menugetf.cgi §397 Equipping motor vehicles with radio receiving sets

- ↑ :View Statutes : Online Sunshine

- ↑ Michigan Penal Code, Excerpt

- ↑ FCC (1993-09-03). PR Docket 91-36: In the Matter of Federal Preemption of State and Local Laws Concerning Amateur Operator Use of Transceivers Capable of Reception Beyond Amateur Service Frequency Allocations — Memorandum Opinion and Order. Federal Communications Commission, 3 September 1993. Retrieved from http://www.arrl.org/files/file/pr91-36.pdf.

- ↑ A partial copy of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 can be found at http://floridalawfirm.com/privacy.html with the following disclaimer: "This document was originally published by Florida Law Firm in 1998. It is no longer current and should not be relied upon for any reason."

- ↑ Radiocommunication Act: An Act respecting radiocommunication in Canada. R.S., 1985, c. R-2, s. 1; 1989, c. 17, s. 2.

- ↑ Gonczol, David (13 April 2012). "Police Hope to End Rebroadcasting of Scanners". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ↑ "Ley de Vías Generales de Comunicación - 73".

External links

- New Zealand Radio Scanning Information and Frequencies website

- The War Against Scanner Encryption

- Heroic Scanner Users

- Scanning Lists and Forums

- Official Online Scanner Feeds

- USA Agencies That List Scanner Frequencies

- USA Local Agencies That Encrypt Radios

- Scanner Feeds Provided by Media Outlets

- Scanner Feeds - Independent

- New Scanner Freqs for USA - 2014 - Updated Weekly

- New Scanner Freqs For USA - 2013

- Scanner Digest Newsletter Website

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scanners. |

- Scanning on the Open Directory Project