Scandinavian flick

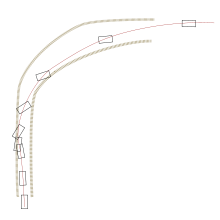

The Scandinavian flick, Finnish flick, Manji Drifting, or Pendulum turn, is a technique used in rallying. While approaching the turn, the driver applies a slight steering input to the opposite direction of the turn, then steering into the turn, while sharply lifting off the throttle and (in some cases, depending on speed and type of layout) lightly applying the brakes. This will cause the car to slide sideways facing slightly away from the turn. Then steering input is applied towards the turn and as the driver releases the brake pedal while still holding down the throttle the car will slingshot itself around the corner to the desired direction. Of course, countersteering will again be required to control the induced oversteer. A recent research paper initiates a mathematical analysis of this technique.[1]

This technique is used to help the driver get around corners that have an increasing radius, but it is also used as a show off as the result of the flick involves the car oversteering heavily.

Origin of the name

Though it is not clear who the first person to invent it was, the technique was named after the Scandinavian rally drivers of the 1960s who widely used it. The front wheel driven cars of the '60s, such as the Mini and the extremely popular Saab 96 in Scandinavia, were easier to turn with if the brake pedal was stabbed to induce weight transfer from rear to front and rear grip reduced until it started to slide. The "flick" part comes from the technique of "flicking" the wheel in a direction opposite of the turn to build up angular momentum.

The Scandinavian rally drivers were, and still are, predominantly the best drivers in Europe for driving in ice and snow conditions, due to their inclement weather in winter months. Because they drove on ice and snow regularly, they were the first drivers to develop techniques to drive at speed in these slippery conditions. The Scandinavian flick was first used by drivers such as Ari Vatanen and Rauno Aaltonen in WRC events on non-cold weather surfaces, and as such, the name has stuck.

Since the concept was understood and developed, it has also found its way into drifting and tarmac driving events. It has even gone as far as Australia, where it has been used to induce oversteer in V8 Supercars.

Physics involved

Every time a vehicle turns, the vehicle resists the change of direction due to inertia. This resistance results in a phenomenon known as understeer, which seems to push the vehicle outward during the turn, this is due to the loss of traction between the front (steering) wheels and the road surface. This is particularly noticeable in Front Wheel Drive vehicle, as the drive to the wheels for a given throttle input overcomes the traction of the tire to the road surface (more power to the driven wheels creates more loss of traction, hence powerful Front Wheel Drive vehicles suffer with understeer). This is partially neutralized by the friction between the tires and the road, so the vehicle rather tilts than slides, but ultimately the front wheels will break traction in a corner. In some rear wheel driven vehicles, the suspension geometry is set up to create "push on" understeer, as this is easier to deal with for the driver than un-predictable and harder to address oversteer). As you abruptly flick the steering wheel in the opposite direction, the inertia of the vehicle that has been trying to slide in the opposite way is added to the force applied by the engine and the friction of the front wheels, thus exceeding the force necessary to break traction between the tires and the tarmac. Since most cars have their engines in the front, the load on the rear tires is less, so they break traction first, effectively causing the rear to slide out. Suddenly lifting the throttle causes additional weight transfer to the front, making the load on the rear wheels even less.

Real life usage

Most cars today are FWD and are prone to understeer. This makes a vehicle stable at high speed but requires larger steer inputs near the limits of adhesion. Skilled drivers are able to allow for understeer by using a maneuver similar to the Scandinavian flick, though with less steering input and control the possible slide by using an opposite lock. In the best of cases, the driver would use the inertia of the feint to make the car enter the bend without initiating a slide. This requires excellent knowledge of the specific car. However, less skilled drivers must not attempt to use this technique, as it can prove very dangerous.

The ability of a vehicle to handle sudden changes in direction at high speeds without sliding or rolling over is assessed through the so-called Moose test. This scenario occurs when the driver is trying to avoid an obstacle (allegedly a moose, or any other large animal that may appear on the road) in his or her lane and then returning to the lane to avoid oncoming traffic. The succession of sharp turns in opposite directions combined with lifting off the throttle is exactly how the Scandinavian flick is performed. Since the technique is used at race speeds, it's not normal for a vehicle to start a slide while driving at cruise speeds.

It is possible to induce oversteer at 30 mph (50 km/h), which is well in the cruise speed range. However, it is not likely that in real life the driver would change the steering input from hard left to hard right within 2 seconds.

Of course, when driving in winter in Nordic countries, one can utilize flick even at low speeds. This technique is trained by some countries in the Scandinavian/Nordic regions during basic driver training. It may also be trained in the UK for professional drivers (Police, Emergency Medical Response, Military) who may be required to drive on snow tires in ice/snow conditions, as a vehicle can behave differently and require different driver skills in winter conditions.

It is frequently used by former racing driver Tiff Needell on the motoring programme Fifth Gear and previously during his time as a presenter on Top Gear.

It was also used in the BBC television series Top Gear, in which Richard Hammond tries to achieve the Scandinavian flick whilst cornering in his "lightweight, mid-engined" Suzuki Super Carry. The result was a less than spectacular roll-over to its side.[2] Additionally, it is featured on Top Gear in an episode in which James May hones his rally skills in the woods and snowy landscape of Finland.

Usage in drifting

In terms of drifting, the Scandinavian flick is classified as a weight transfer drift. It is also known as a Feint drift or Inertia drift. It's widely used in rallying, because it is simple to perform and does not require engine power, nor does it cause a loss of speed at the exit of the corner. A drawback of the technique is that it requires somewhat wider tracks than the other drifting techniques.

Many drift drivers will utilise the feint or weight transfer drift on track, in order to send the rear of their car into a more accentuated drift where the track width allows them. In most situations, this is preferable to drivers of lower powered cars, who cannot induce a drift with engine power alone, but it is also useful to drivers of turbo charged cars, when they find that their car is not "on boost". Many Japanese based vehicles use smaller capacity engines with larger turbos, so can "fall" off the power band created by the forced induction. The alternative methods to create power pre-corner include the feint drift incorporated with a "clutch kick", which starts the weight transfer, but allow the engine to free-rev and create boost pressure in the turbo to create more power to break the traction of the rear wheels when the clutch re-engages on the drivetrain with the car unsettled.

Dangers

There are two basic dangers when performing the Scandinavian flick

- If the center of gravity is too high (as in a SUV or a tall van), there's a great chance the vehicle would roll over instead of sliding.

- It takes practice to learn how to control the vehicle during the slide. A less experienced driver would be prone to overcompensating for the slide and driving off the bend.

Also, a drift is not likely to occur if the camber of the rear wheels is set too negative. On the other hand, if the camber of the front wheels is set too positive, they will break traction in the same moment the rear ones do, so the car will slide uncontrollably rather than pivoting around the front wheels.

See also

References

- ↑ Efstathios Velenis, Panagiotis Tsiotras and Jianbo Lu, "Modeling Aggressive Maneuvers on Loose Surfaces: The Cases of Trail-Braking and Pendulum-Turn," European Control Conference, Kos, Greece, July 2-5, 2007

- ↑ "Top Gear Man with a Van Challange". Top Gear Series 8 Episode 8. Retrieved 16 June 2012.