Saturated fat

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

|

| See also |

Saturated fat is fat that consists of triglycerides containing only saturated fatty acids. Saturated fatty acids have no double bonds between the individual carbon atoms of the fatty acid chain. That is, the chain of carbon atoms is fully "saturated" with hydrogen atoms. There are many kinds of naturally occurring saturated fatty acids, which differ mainly in number of carbon atoms, from 3 carbons (propionic acid) to 36 (hexatriacontanoic acid).

Various fats contain different proportions of saturated and unsaturated fat. Examples of foods containing a high proportion of saturated fat include animal fats such as cream, cheese, butter, and ghee; suet, tallow, lard, and fatty meats; as well as certain vegetable products such as coconut oil, cottonseed oil, palm kernel oil, chocolate, and many prepared foods.[1]

Fat profiles

While nutrition labels regularly combine them, the saturated fatty acids appear in different proportions among food groups. Lauric and myristic acids are most commonly found in "tropical" oils (e.g., palm kernel, coconut) and dairy products. The saturated fat in meat, eggs, chocolate, and nuts is primarily the triglycerides of palmitic and stearic acids.

| Food | Lauric acid | Myristic acid | Palmitic acid | Stearic acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coconut oil | 47% | 18% | 9% | 3% |

| Palm oil | 0.1% | 1% | 44% | 5% |

| Butter | 3% | 11% | 29% | 13% |

| Ground beef | 0% | 4% | 26% | 15% |

| Dark chocolate | 0% | 1% | 34% | 43% |

| Salmon | 0% | 1% | 29% | 3% |

| Egg yolks | 0% | 0.3% | 27% | 10% |

| Cashews | 2% | 1% | 10% | 7% |

| Soybean oil | 0% | 0% | 11% | 4% |

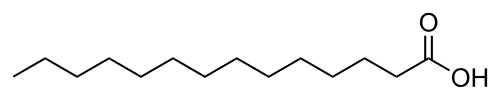

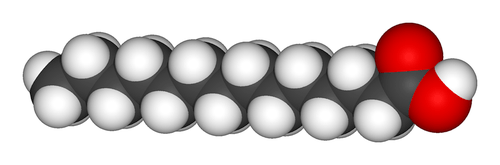

Examples of saturated fatty acids

Some common examples of fatty acids:

- Butyric acid with 4 carbon atoms (contained in butter)

- Lauric acid with 12 carbon atoms (contained in coconut oil, palm kernel oil, and breast milk)

- Myristic acid with 14 carbon atoms (contained in cow's milk and dairy products)

- Palmitic acid with 16 carbon atoms (contained in palm oil and meat)

- Stearic acid with 18 carbon atoms (also contained in meat and cocoa butter)

Association with diseases

Since the 1950s, it has been commonly believed that consumption of foods containing high amounts of saturated fatty acids (including meat fats, milk fat, butter, lard, coconut oil, palm oil, and palm kernel oil) is potentially less healthy than consuming fats with a lower proportion of saturated fatty acids. Sources of lower saturated fat but higher proportions of unsaturated fatty acids include olive oil, peanut oil, canola oil, avocados, safflower, corn, sunflower, soy, and cottonseed oils.[6]

Cardiovascular disease

A meta-analysis of 21 studies considered the effects of saturated fat intake and found that "Intake of saturated fat was not associated with an increased risk of CHD (coronary heart disease), stroke, or CVD (cardiovascular disease)."[7] Nevertheless, still some medical, heart-health, and governmental authorities, such as the World Health Organization,[8] the American Dietetic Association,[9] the Dietitians of Canada,[9] the British Dietetic Association,[10] American Heart Association,[11] the British Heart Foundation,[12] the World Heart Federation,[13] the British National Health Service,[14] the United States Food and Drug Administration,[15] and the European Food Safety Authority[16] advise that saturated fat is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Numerous systematic reviews have examined the relationship between saturated fat and cardiovascular disease:

| Systematic review | Relationships between cardiovascular disease and saturated fatty acids (SFA) |

|---|---|

| Hooper, 2011[17] | Reducing saturated fat in diets reduced the risk of having a cardiovascular event by 14 percent (no reduction in mortality). |

| Micha, 2010[18] | Evidence for the effects of saturated fatty acid consumption on vascular function, insulin resistance, diabetes, and stroke is mixed, with many studies showing no clear effects, highlighting a need for further investigation |

| Mozaffarian, 2010[19] | These findings provide evidence that consuming polyunsaturated fats (PUFA) in place of SFA reduces Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) events in randomized controlled trials (RCT). Replacing saturated fats with PUFAs as percentage of calories strongly reduced CHD mortality. |

| Siri-Tarino, 2010[20] | 5–23 years of follow-up of 347,747 subjects, 11,006 developed CHD or stroke. A meta-analysis of prospective epidemiologic studies showed that there is no significant evidence for concluding that dietary saturated fat is associated with an increased risk of CHD or CVD. |

| Danaei, 2009[21] | Low PUFA intake has an 1-5% Increased risk of ischemic heart disease: Low dietary PUFA (in replacement of SFA). age 30–44 Increase in RR 1.05. |

| Mente, 2009[22] | Single-nutrient RCTs have yet to evaluate whether reducing saturated fatty acid intake lowers the risk of CHD events. For polyunsaturated fatty acid intake, most of the RCTs have not been adequately powered and did not find a significant reduction in CHD outcomes. |

| Skeaff, 2009[23] | Intake of SFA was not significantly associated with CHD mortality, with a RR of 1.14. Moreover, there was no significant association with CHD death. Intake of PUFA was strongly significantly associated with CHD mortality, with a RR of 1.25. The Health Professionals Follow-up Study and the EUROASPIRE study results mirrored those of total PUFA; intake of linoleic acid was significantly associated with CHD mortality. |

| Jakobsen, 2009[24] | "The associations suggest that replacing saturated fatty acids with polyunsaturated fatty acids rather than monounsaturated fatty acids or carbohydrates prevents CHD over a wide range of intakes." |

| Van Horn, 2008[25] | 25-35% fats but <7% SFA and TFA reduces risk. |

| Hooper, 2001[26] | Despite decades of effort and many thousands of people randomised, there is still only limited and inconclusive evidence of the effects of modification of total, saturated, monounsaturated, or polyunsaturated fats on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Study conclusion: "There is a small but potentially important reduction in cardiovascular risk with reduction or modification of dietary fat intake, seen particularly in trials of longer duration." |

| Hu, 1999[27] | Based on the data from the Nurses’ Health Study, we estimated that substitution of the fat from 1 ounce of nuts for equivalent energy from carbohydrate in an average diet was associated with a 30% reduction in CHD risk and the substitution of nut fat for saturated fat was associated with 45% reduction in risk. |

| Truswell, 1994[28] | Decrease SFA and cholesterol intake, partial replacement with PUFA: 6% reduced deaths, 13% reduced events. |

While many studies have found that including polyunsaturated fats in the diet in place of saturated fats produces more beneficial CVD outcomes, the effects of substituting monounsaturated fats or carbohydrates are unclear.[29][30]

Dyslipidemia

The consumption of saturated fat is generally considered a risk factor for dyslipidemia, which in turn is a risk factor for some types of cardiovascular disease.[31][32][33][34][35]

There are strong, consistent, and graded relationships between saturated fat intake, blood cholesterol levels, and the mass occurrence of cardiovascular disease. The relationships are accepted as causal.[36][37] Abnormal blood lipid levels, that is high total cholesterol, high levels of triglycerides, high levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL, "bad" cholesterol) or low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL, "good" cholesterol) cholesterol all increase the risk of heart disease and stroke.[13]

Meta-analyses have found a significant relationship between saturated fat and serum cholesterol levels.[38] High total cholesterol levels, which may be caused by many factors, are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.[39][40] However, other indicators measuring cholesterol such as high total/HDL cholesterol ratio are more predictive than total serum cholesterol.[40] In a study of myocardial infarction in 52 countries, the ApoB/ApoA1 (related to LDL and HDL, respectively) ratio was the strongest predictor of CVD among all risk factors.[41] There are other pathways involving obesity, triglyceride levels, insulin sensitivity, endothelial function, and thrombogenicity, among others, that play a role in CVD, although it seems, in the absence of an adverse blood lipid profile, the other known risk factors have only a weak atherogenic effect.[42] Different saturated fatty acids have differing effects on various lipid levels.[43]

Cancer

Breast cancer

A meta-analysis published in 2003 found a significant positive relationship in both control and cohort studies between saturated fat and breast cancer.[44] However two subsequent reviews have found weak or insignificant associations of saturated fat intake and breast cancer risk,[45][46] and note the prevalence of confounding factors.[45][47]

Colorectal cancer

A systematic literature review published by the World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research in 2007 found limited but consistent evidence for a positive relationship between animal fat and colorectal cancer.[48]

Ovarian cancer

A meta-analysis of eight observational studies published in 2001 found a statistically significant positive relationship between saturated fat and ovarian cancer.[49] However, a 2013 study found that a pooled analysis of 12 cohort studies observed no association between total fat intake and ovarian cancer risk. Further analysis revealed that omega-3 fatty acids were protective against ovarian cancer and that trans fats were a risk factor.[50] This study revealed that histological subtypes should be examined in determining the impact of dietary fat on ovarian cancer, rather than an oversimplified focus on total fat intake.

Prostate cancer

Some researchers have indicated that serum myristic acid[51][52] and palmitic acid[52] and dietary myristic[53] and palmitic[53] saturated fatty acids and serum palmitic combined with alpha-tocopherol supplementation[51] are associated with increased risk of prostate cancer in a dose-dependent manner. These associations may, however, reflect differences in intake or metabolism of these fatty acids between the precancer cases and controls, rather than being an actual cause.[52]

Bones

Mounting evidence indicates that the amount and type of fat in the diet can have important effects on bone health. Most of this evidence is derived from animal studies. The data from one study indicated that bone mineral density is negatively associated with saturated fat intake, and that men may be particularly vulnerable.[54]

Dietary recommendations

Recommendations to reduce or limit dietary intake of saturated fats are made by Health Canada,[55] the US Department of Health and Human Services,[56] the UK Food Standards Agency,[57] the Australian Department of Health and Aging,[58] the Singapore Government Health Promotion Board,[59] the Indian Government Citizens Health Portal,[60] the New Zealand Ministry of Health,[61] the Food and Drugs Board Ghana,[62] the Republic of Guyana Ministry of Health,[63] and Hong Kong's Centre for Food Safety.[64]

A 2004 statement released by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) determined that "Americans need to continue working to reduce saturated fat intake…"[65] In addition, reviews by the American Heart Association led the Association to recommend reducing saturated fat intake to less than 7% of total calories according to its 2006 recommendations.[66][67] This concurs with similar conclusions made by the US Department of Health and Human Services, which determined that reduction in saturated fat consumption would positively affect health and reduce the prevalence of heart disease.[68]

In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) expert consultation report concluded that "intake of saturated fatty acids is directly related to cardiovascular risk. The traditional target is to restrict the intake of saturated fatty acids to less than 10% of daily energy intake and less than 7% for high-risk groups. If populations are consuming less than 10%, they should not increase that level of intake. Within these limits, intake of foods rich in myristic and palmitic acids should be replaced by fats with a lower content of these particular fatty acids. In developing countries, however, where energy intake for some population groups may be inadequate, energy expenditure is high and body fat stores are low (BMI <18.5 kg/m2). The amount and quality of fat supply has to be considered keeping in mind the need to meet energy requirements. Specific sources of saturated fat, such as coconut and palm oil, provide low-cost energy and may be an important source of energy for the poor."[69]

Dr. German and Dr. Dillard of University of California and Nestle Research Center in Switzerland, in their 2004 review, pointed out that "no lower safe limit of specific saturated fatty acid intakes has been identified" and recommended that the influence of varying saturated fatty acid intakes against a background of different individual lifestyles and genetic backgrounds should be the focus in future studies.[70]

Blanket recommendations to lower saturated fat were criticized at a 2010 conference debate of the American Dietetic Association for focusing too narrowly on reducing saturated fats rather than emphasizing increased consumption of healthy fats and unrefined carbohydrates. Concern was expressed over the health risks of replacing saturated fats in the diet with refined carbohydrates, which carry a high risk of obesity and heart disease, particularly at the expense of polyunsaturated fats which may have health benefits. None of the panelists recommended heavy consumption of saturated fats, emphasizing instead the importance of overall dietary quality to cardiovascular health.[71]

Molecular description

Carbon atoms are also implicitly drawn, as they are portrayed as intersections between two straight lines. "Saturated," in general, refers to a maximum number of hydrogens bonded to each carbon of the polycarbon tail as allowed by the Octet Rule. This also means that only single bonds (sigma bonds) will be present between adjacent carbon atoms of the tail.

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ Saturated fat food sources

- ↑ "USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 20". United States Department of Agriculture. 2007.

- ↑ nutritiondata.com → Oil, vegetable, sunflower Retrieved on September 27, 2010

- ↑ nutritiondata.com → Egg, yolk, raw, fresh Retrieved on August 24, 2009

- ↑ "Feinberg School > Nutrition > Nutrition Fact Sheet: Lipids". Northwestern University. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20.

- ↑ "Dietary fats: Know which types to choose". Mayo Clinic. 2011-02-15. Retrieved 2011-09-02.

- ↑ http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/early/2010/01/13/ajcn.2009.27725.abstract. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation (2003). Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (WHO technical report series 916). World Health Organization. pp. 81–94. ISBN 92-4-120916-X. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Kris-Etherton, PM; Innis, S; American Dietetic, Association; Dietitians Of, Canada (September 2007). "Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: Dietary Fatty Acids". Journal of the American Dietetic Association 107 (9): 1599–1611 [1603]. PMID 17936958. Retrieved 2011-03-18.

- ↑ "Food Fact Sheet - Cholesterol". British Dietetic Association. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions about Fats". American Heart Association. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ "Saturated Fat". Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors". Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ↑ "Lower your cholesterol". National Health Service. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ↑ "Nutrition Facts at a Glance - Nutrients: Saturated Fat". Food and Drug Administration. 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ↑ "Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol". European Food Safety Authority. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ Hooper L, Summerbell CD, Thompson R, Sills D, Roberts FG, Moore H, Smith GD (July 2011). "Reduced or modified dietary fat for preventing cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Library (7): CD002137. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002137.pub2. PMID 21735388.

- ↑ Micha, Renata Mozaffarian, Dariush (October 2010). "Saturated Fat and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors, Coronary Heart Disease, Stroke, and Diabetes: a Fresh Look at the Evidence". Lipids 45 (10): 893–905. doi:10.1007/s11745-010-3393-4. PMC 2950931. PMID 20354806.

- ↑ Mozaffarian D, Micha R, Wallace S (March 2010). "Effects on Coronary Heart Disease of Increasing Polyunsaturated Fat in Place of Saturated Fat: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". In Katan, Martijn B. PLoS Medicine 7 (3): 1–10. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000252. ISSN 1549-1277. PMC 2843598. PMID 20351774.

- ↑ Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM (March 2010). "Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 91 (3): 535–46. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27725. PMC 2824152. PMID 20071648.

- ↑ Danaei G et al. (April 2009). "The Preventable Causes of Death in the United States: Comparative Risk Assessment of Dietary, Lifestyle, and Metabolic Risk Factors". In Hales, Simon. PLoS Medicine 6 (4): e1000058. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. ISSN 1549-1277. PMC 2667673. PMID 19399161. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ↑ Mente A, de Koning L, Shannon HS, Anand SS (April 2009). "A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease". Arch. Intern. Med. 169 (7): 659–69. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.38. PMID 19364995. Free full-text

- ↑ Skeaff, Murray; Miller, Jody (15 September 2009). "Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: Summary of evidence from prospective cohort and randomised controlled trials". Annals of nutrition & metabolism 55 (1–3): 173–U287. doi:10.1159/000229002. ISSN 0250-6807. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- ↑ Jakobsen, MU; O'Reilly, EJ; Heitmann, BL; Pereira, MA; Bälter, K; Fraser, GE; Goldbourt, U; Hallmans, G et al. (2009). "Major types of dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of 11 cohort studies". The American journal of clinical nutrition 89 (5): 1425–32. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27124. PMC 2676998. PMID 19211817.

- ↑ Van Horn L et al (February 2008). "The evidence for dietary prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease". Journal of the American Dietetic Association 108 (2): 287–331. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2007.10.050. ISSN 0002-8223. PMID 18237578.

- ↑ Hooper, L et al. (31 Mar 2001). "Dietary fat intake and prevention of cardiovascular disease: systematic review". British Medical Journal 322 (7289): 757–63. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 30550. PMID 11282859.

- ↑ Hu FB, Stampfer MJ (November 1999). "Nut consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a review of epidemiologic evidence". Current Atherosclerosis Reports 1 (3): 204–209. doi:10.1007/s11883-999-0033-7. PMID 11122711.

- ↑ Truswell, A. Stewart (February 1994). "Review of dietary intervention studies: effect on coronary events and on total mortality". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Medicine 24 (1): 98–106. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.1994.tb04444.x. PMID 8002875.

- ↑ Astrup A, Dyerberg J, Elwood P, et al. (April 2011). "The role of reducing intakes of saturated fat in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: where does the evidence stand in 2010?". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 93 (4): 684–8. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.004622. PMC 3138219. PMID 21270379.

- ↑ Jebb SA, Lovegrove JA, Griffin BA, et al. (October 2010). "Effect of changing the amount and type of fat and carbohydrate on insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular risk: the RISCK (Reading, Imperial, Surrey, Cambridge, and Kings) trial". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 92 (4): 748–58. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.29096. PMID 20739418.

- ↑ Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom. Position Statement on Fat [Retrieved 2011-01-25].

- ↑ Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation (2003). "Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ "Cholesterol". Irish Heart Foundation. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (December 2010). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 (7th Edition). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Cannon, Christopher; O'Gara, Patrick (2007). Critical Pathways in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2nd Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 243.

- ↑ European Society of Cardiology (2007). "European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary". European Heart Journal 28 (19): 2375–2414. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm316. PMID 17726041.

- ↑ Labarthe, Darwin (2011). "Chapter 17 What Causes Cardiovascular Diseases?". Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge (2 ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

- ↑ Clarke, R; Frost, C; Collins, R; Appleby, P; Peto, R (1997). "Dietary lipids and blood cholesterol: quantitative meta-analysis of metabolic ward studies". BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 314 (7074): 112–7. PMC 2125600. PMID 9006469.

- ↑ Bucher, HC; Griffith, LE; Guyatt, GH (February 1999). "Systematic review on the risk and benefit of different cholesterol-lowering interventions". Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology 19 (2): 187–195. PMID 9974397.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R (December 2007). "Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths". Lancet 370 (9602): 1829–39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. PMID 18061058.

- ↑ Labarthe, Darwin (2011). "Chapter 11 Adverse Blood Lipid Profile". Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge (2 ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

- ↑ Labarthe, Darwin (2011). "Chapter 11 Adverse Blood Lipid Profile". Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge (2 ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

- ↑ Thijssen, MA; Mensink RP (2005). "Fatty Acids and Atherosclerotic Risk". In von Eckardstein A. Atherosclerosis: Diet and Drugs. Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 171–2. ISBN 978-3-540-22569-0.

- ↑ Boyd NF, Stone J, Vogt KN, Connelly BS, Martin LJ, Minkin S (November 2003). "Dietary fat and breast cancer risk revisited: a meta-analysis of the published literature". British Journal of Cancer 62 (9): 1672–1685. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601314. PMC 2394401. PMID 14583769.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Hanf V, Gonder U (2005-12-01). "Nutrition and primary prevention of breast cancer: foods, nutrients and breast cancer risk.". European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology 123 (2): 139–149. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.05.011. PMID 16316809.

- ↑ Lof M, Weiderpass E (February 2009). "Impact of diet on breast cancer risk.". Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology 21 (1): 80–85. doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e32831d7f22. PMID 19125007.

- ↑ Freedman LS, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A, Potischman N (Mar–Apr 2008). "Methods of Epidemiology: Evaluating the Fat–Breast Cancer Hypothesis – Comparing Dietary Instruments and Other Developments". Cancer journal (Sudbury, Mass.) 14 (2): 69–74. doi:10.1097/PPO.0b013e31816a5e02. PMC 2496993. PMID 18391610.

- ↑ "4- Food and Drinks" (pdf). Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. World Cancer Research Fund. 2007. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-9722522-2-5. Retrieved 2011-09-01.

- ↑ Huncharek M, Kupelnick B (2001). "Dietary fat intake and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis of 6,689 subjects from 8 observational studies". Nutrition and Cancer 40 (2): 87–91. doi:10.1207/S15327914NC402_2. PMID 11962260.

- ↑ http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/meeting_abstract/73/8_MeetingAbstracts/148

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Männistö S, Pietinen P, Virtanen MJ, et al. (December 2003). "Fatty acids and risk of prostate cancer in a nested case-control study in male smokers". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 12 (12): 1422–8. PMID 14693732.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Crowe FL, Allen NE, Appleby PN, et al. (November 2008). "Fatty acid composition of plasma phospholipids and risk of prostate cancer in a case-control analysis nested within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 88 (5): 1353–63. PMID 18996872.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Kurahashi N, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Tsugane AS (April 2008). "Dairy product, saturated fatty acid, and calcium intake and prostate cancer in a prospective cohort of Japanese men". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 17 (4): 930–7. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2681. PMID 18398033.

- ↑ Corwin, R. L.; Hartman, T. J.; MacZuga, S. A.; Graubard, B. I. (2006). "Dietary saturated fat intake is inversely associated with bone density in humans: Analysis of NHANES III". The Journal of nutrition 136 (1): 159–165. PMID 16365076.

- ↑ "Saturated and Trans Fats". Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ↑ "Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005". Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ↑ "Saturated Fat". Retrieved 2010-12-02.1

- ↑ "Australian Dietary Guidelines and the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating". Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ↑ "Getting the Fats Right!". Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ↑ "Citizens Health Knowledge Centre Nutrition". Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ↑ "New Zealand Food and Nutrition Guideline Statements for Healthy Adults". Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ↑ "Food and Drugs Board Regulating for Your Safety Eating Healthy". Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ↑ "Hypertension (High Blood Pressure)". Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ↑ "Nutrition Labelling". Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ↑ "Trends in Intake of Energy, Protein, Carbohydrate, Fat, and Saturated Fat — United States, 1971–2000". Centers for Disease Control. 2004.

- ↑ Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, et al. (July 2006). "Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee". Circulation 114 (1): 82–96. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176158. PMID 16785338.

- ↑ Smith SC, Jackson R, Pearson TA, et al. (June 2004). "Principles for national and regional guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention: a scientific statement from the World Heart and Stroke Forum". Circulation 109 (25): 3112–21. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000133427.35111.67. PMID 15226228.

- ↑ "Dietary Guidelines for Americans" (pdf). United States Department of Agriculture. 2005.

- ↑ Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation (2003). "Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (WHO technical report series 916)". World Health Organization. pp. 81–94. ISBN 92-4-120916-X. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ German, J Bruce; Dillard, Cora J (September 2004). "Saturated fats: what dietary intake?". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 80 (3): 550–559. PMID 15321792. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ↑ Zelman, K. (2011). "The Great Fat Debate: A Closer Look at the Controversy—Questioning the Validity of Age-Old Dietary Guidance". Journal of the American Dietetic Association 111 (5): 655–658. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.03.026. PMID 21515106.

Further reading

- Feinman Richard D (2010). "Saturated Fat and Health: Recent Advances in Research". Lipids 45 (10): 891–892. doi:10.1007/s11745-010-3446-8. PMID 20827513.

- Howard BV, Van Horn L, Hsia J, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kuller LH, LaCroix AZ, Langer RD et al. (2006). "Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial". Journal of the American Medical Association 295 (6): 655–66. doi:10.1001/jama.295.6.655. PMID 16467234.

- Zelman Kathleen, Willett Walter C., Kuller Lewis H., Mozaffarian Dariush, Lichtenstein Alice H. (2011). "The Great Fat Debate". Journal of the American Dietetic Association 111 (5): 655–677. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.03.026. PMID 21515106.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||