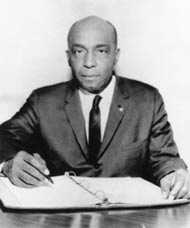

Samuel Wilbert Tucker

| Samuel Wilbert Tucker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

June 18, 1913 Alexandria, Virginia, United States |

| Died |

October 19, 1990 (aged 77) Richmond, Virginia, United States |

Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Alma mater | Howard University |

| Occupation | Civil rights attorney |

| Spouse(s) | Julia E. Spaulding Tucker |

Samuel Wilbert Tucker (June 18, 1913 – October 19, 1990) was an American lawyer and a cooperating attorney with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). As a founding partner in the Richmond, Virginia firm of Hill, Tucker and Marsh, he is best remembered for one of his several civil rights cases before the Supreme Court of the United States: Green v. County School Board of New Kent County which, according to The Encyclopedia of Civil Rights In America, "did more to advance school integration than any other Supreme Court decision since Brown."[1] He is also remembered for organizing a 1939 sit-in at the then-segregated Alexandria, Virginia public library.[2][3]

Early life and education

Tucker was born in Alexandria, Virginia on June 18, 1913. He later said: "I got involved in the civil rights movement on June 18, 1913, in Alexandria. I was born black." At 14, he and his brothers were involved in an incident in Alexandria when they refused to give up a seat on a streetcar to a white person.

He also set his sights on becoming a lawyer at an early age, starting to read law books when he was about 10. Having earned his undergraduate degree from Howard University in 1933, he qualified for the Virginia bar exam based on his studies in a law office.[1]

Legal career

Tucker was admitted to the state bar in 1934 and began practicing in Alexandria.

Alexandria library sit-in

In 1939, Tucker organized a sit-in at Alexandria's public library, which refused to issue library cards to black residents. On August 21, five young black men whom Tucker had recruited and instructed – William Evans, Otto L. Tucker, Edward Gaddis, Morris Murray, and Clarence Strange – entered the library one by one, requested applications for library cards and, when refused, each one took a book off the shelf and sat down in the reading room until they were removed by the police. Tucker had instructed the men to dress well, speak politely and offer no resistance to the police so as to minimize the chance of the men being found guilty of disorderly conduct or resisting arrest. Tucker defended the men in the ensuing legal actions which resulted in the protestors not being convicted of disorderly conduct and in a branch library being established for blacks.[2][4] While the sit-in received a four paragraph story in the local Alexandria Gazette newspaper and brief mention in the Washington Post, the Chicago Defender ran the story on its front page accompanied by a photograph of the arrest, noting that the protest was being viewed as a "test case" in Virginia.[5][6] Other African American newspapers covered the legal action, reporting such developments as Tucker's cross-examination of the police, bringing forth an admission that had the men been white they would not have been arrested under similar circumstances.[2][7] While Tucker succeeded in defending the sit-in participants, he was not satisfied with the separate but equal resolution of creating a new branch library for blacks. In a 1940 letter to the librarian of the whites-only library, Tucker stated that he would refuse to accept a card to the new blacks-only branch library in lieu of a card to be used at the existing library.[8]

The photograph of the sit-in participants in jackets and ties calmly but resolutely being escorted from the library by uniformed police has itself become a learning aid in Alexandria. Periodically, the city has commemorated the sit-in and used it as a teaching opportunity about the Jim Crow segregation era, with students from Samuel W. Tucker Elementary donning similar attire, acting out the sit-in events and posing in recreations of the photograph.[5][9][10]

War and moves to Emporia and Richmond

World War II interrupted his practice and Tucker entered the Army, serving in the 366th Infantry in combat in Italy and rising to the rank of major. After the war, Tucker moved his law practice to Emporia, Virginia. During the 1960s he joined Oliver Hill and Henry L. Marsh III to form the law firm Hill, Tucker & Marsh in Richmond, Virginia. As the black civil rights struggle developed during the postwar era, Tucker played a central role in its legal battles in Virginia.[1] From 1960 to 1962, the Virginia State Bar repeatedly attempted to disbar Tucker by alleging unprofessional conduct related to cases Tucker pursued on behalf of the NAACP. The NAACP rallied to his defense in fighting what it viewed as an attempt to derail legal desegregation in Virginia and the case was repeatedly dismissed/non-suited.[11][12][13]

Cooperating attorney for the NAACP

Tucker was the principal lawyer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in a number of post-Brown school desegregation cases. He participated in the long legal struggle to reopen the public schools in Prince Edward County, Virginia, closed by the county to avoid desegregation.[14] Tucker also participated in the lawsuit that ended the state tuition grant program that allowed white children to attend segregated academies at public expense[15] and was involved in cases that challenged the death penalty as being racially biased.[16] He fought against racial discrimination in jury selection.[17] In 1967, for example, he had about 150 civil rights cases before state and federal courts.[1]

Tucker's greatest legal achievement was probably Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, which challenged a freedom-of-choice plan the board had enacted to desegregate the county schools on a voluntary basis. The case went to the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled in May 1968 that the freedom-of-choice plan was an inadequate remedy. The justices determined that school boards had an "affirmative duty" to desegregate their schools.[1]

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund named him lawyer of the year in 1966.[18]

In addition to bringing cases, Tucker was also active in the leadership of the NAACP, serving as chairman of the legal staff of the Virginia State Conference and representing Virginia, Maryland and the District of Columbia on the National Board of Directors.[19]

In 1976, the NAACP honored Tucker by awarding him the William Robert Ming Advocacy Award for the spirit of financial and personal sacrifice displayed in his legal work.[20]

Death and legacy

Tucker died on October 19, 1990. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[1]

In 1998, Emporia, Virginia dedicated a monument in his honor. The monument's inscription called Tucker "an effective, unrelenting advocate for freedom, equality and human dignity – principles he loved – things that matter."[1]

In 2000, Alexandria, Virginia dedicated a new school, Samuel W. Tucker Elementary School, to Tucker in honor of his life's work in the service of desegregation and education.[21]

Also in 2000, the Richmond, Virginia City Council voted to rename a bridge after Tucker, an action that was a matter of some controversy.[22]

In 2001, the Young Lawyers Conference, a conference of the Virginia State Bar, implemented the Oliver Hill/Samuel Tucker Institute, named for legendary civil rights attorneys Oliver Hill and Samuel Tucker. The Institute seeks to reach future lawyers, in particular minority candidates, at an early age to provide them with exposure and opportunity to explore the legal profession they might not otherwise receive.[23]

Since 2001, the Oliver W. Hill & Samuel W. Tucker Scholarship Committee has presented scholarships to deserving first year law students at Virginia law schools and Howard University.[24]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Samuel Wilbert Tucker". Richmond Times. February 2000. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "America's First Sit-Down Strike: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In". City of Alexandria. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ↑ "1939 Alexandria Library Sit-in". City of Alexandria. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ↑ "Remembering Injustices and Triumphs". Washington Post. January 30, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Pope, Michael (August 27, 2009). "Shhh! History Being Made: Remembering segregation and defiance on 70th anniversary of Alexandria’s civil-rights protest at library.". Alexandria Gazette Packet. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- ↑ "Five Colored Youths Stage Alexandria Library 'Sit-Down': All to Face Court Today on Charge Of Disorderly Conduct for Efforts to Compel Extension of Book Privileges". Washington Post. 1939-08-22. p. 3. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ↑ "Va. Library War in Court Again". Baltimore Afro-American. September 2, 1939. p. 12. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ↑ "Document of the Month: Letter from Samuel W. Tucker to Alexandria Library, February 13, 1940". City of Alexandria. February 2004. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ↑ "Alexandria Library Civil Rights Sit-In 70th Anniversary". City of Alexandria. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ↑ "They led the way with 1939 Alexandria library protest: Re-enactment on 60th anniversary.". Washington Times. August 22, 1999. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ↑ "Case Dismissed". The Crisis. January 1961. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ↑ "Va. Court Drops Charges Against NAACP Attorney". Baltimore Afro-American. February 3, 1962. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ↑ S.J. Ackerman (June 11, 2000). "The Trials of S.W. Tucker; The Alexandria-born lawyer wasn't one of the most famous leaders of the civil rights struggle. But his enemies always knew who he was.". Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ↑ "Virginia Must Reopen Schools Claims State's Supreme Court". The Sumter Daily Item (South Carolina). November 28, 1961. Retrieved 2010-07-10. "Samuel W. Tucker, attorney for the plaintiffs said, 'The court indicated its support for my chief argument for reopening schools – that the county is required to do so by the constitution.'"

- ↑ "Negro Attorney Hits Virginia School Plan". The Gadsen Times (Alabama). December 15, 1964. Retrieved 2010-07-10. "Virginia may not 'tie its own hands' and say it is not responsible when white children use state tuition grants to attend segregated private schools."

- ↑ Margaret Edds (2003). An expendable man: the near-execution of Earl Washington, Jr. NYU Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-0-8147-2222-0. "The Martinsville Seven case was the first in which attorneys attacked the death penalty by using statistical evidence to prove systemic discrimination.... [I]t struck [Samuel Tucker and Roland Ealey] 'like a bolt of lightning' when they realized that between 1908 and 1950, forty-five backs—and no whites—had been executed in Virginia for the sole crime of rape."

- ↑ Tucker, S.W. (May 1966). "Racial Discrimination in Jury Selection in Virginia". Virginia Law Review 52 (4): 736–750. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ↑ "LOCAL LAWYER, ADVOCATE OF CIVIL RIGHTS DIES AT 77". Richmond Times – Dispatch. October 19, 1990. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ↑ "A Guide to the Samuel Wilbert Tucker Collection: Collection Number M56". Virginia Commonwealth University. 2001. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ↑ "NAACP Legal Department Awards". NAACP. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ↑ "Dedicating Our School to Mr. Tucker". City of Alexandria. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ↑ Carrie Johnson (February 15, 2000). "TWO BRIDGES TO GET NEW NAMES GENERALS ARE OUT; RIGHTS ACTIVISTS ARE IN". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- ↑ "Oliver Hill/Samuel Tucker Prelaw Institute". Virginia State Bar. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ↑ "Scholarship History" (pdf). Greater Richmond Bar Foundation. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

Further reading

- Ackerman, S.J. (Summer 2000). "Samuel Wilbert Tucker: The Unsung Hero of the School Desegregation Movement". Journal of Blacks in Higher Education 28: 98–103. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- Jill Ogline Titus (2011). Brown's Battleground: Students, Segregationists, and the Struggle for Justice in Prince Edward County, Virginia. University of North Carolina Press. p. 126ff. ISBN 978-0-8078-3507-4.

- Smith, J. Douglas (2002). Managing white supremacy: race, politics, and citizenship in Jim Crow Virginia. University of North Carolina Press. p. 259ff. ISBN 978-0-8078-2756-7.

- Wallenstein, Peter (2004). Blue Laws and Black Codes: Conflict, Courts, and Change in Twentieth-Century Virginia. University of Virginia Press. p. 83ff. ISBN 978-0-8139-2261-4.

External links

- America's First Sit-Down Strike: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In – Alexandria Black History Museum lesson plan

- 1956 Television Interview of Samuel Tucker – Archived by University of Virginia

- The Civil Rights Movement in Virginia: The Closing of Prince Edward County's Schools – Virginia Historical Society

- 70th Anniversary of Alexandria Library’s Historic Sit-in – City of Alexandria podcast

- 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-in Video - C-SPAN

|